K-HOLE Investigates the Phenomenon of CREATIVE LEADERSHIP

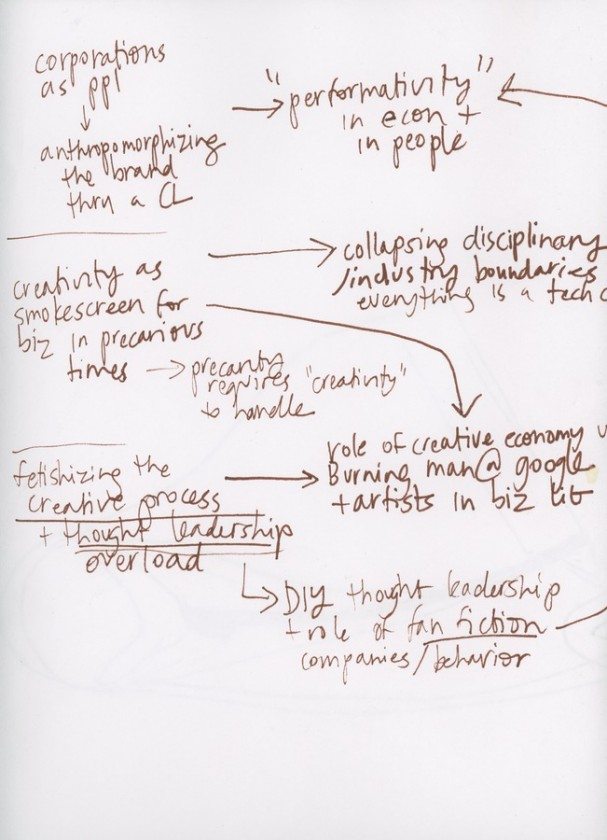

When 032c asked us to explore the idea of creative leadership, our first question was: does that even exist? We decided to ask FLORIANE DE SAINT PIERRE, the luxury brand headhunter who placed Christopher Bailey at Burberry and Alexander Wang at Balenciaga. We emailed VENKATESH RAO, a rogue management consultant who’s accused start-ups of being “design fictions masquerading as businesses.” Floriane uses the term “creative leadership” to describe a new paradigm – piloted in fashion but now spreading to other industries – in which creative directors are taking over the role of the CEO. This dossier investigates this new class of mutants and its relationship to innovation and big data.

BECAUSE CREATIVITY

Creativity is kinky. It’s a strategic knowledge of how to use old things to get new results – necessary in a world that seems increasingly prone only to burps of progress rather than long, clean stretches. The forward momentum of time, capitalism, and sheer boredom demands that we eke out newness even in the moments when everything feels pretty much the same.

Creativity and innovation are auspicious words. They recognize that we don’t really know where new things come from. Innovation simply descends out of the realm of heavenly possibility with an unknowable deistic logic. If this all sounds a little religious, it is – we didn’t kill God, we just stopped anthropomorphizing him. Instead of actively attributing the unknown to the divine, we just presume someone else understands what’s going on.

Creativity no longer has an antonym. Once upon a time the opposite of creativity was destruction: Genesis and Revelation, yin and yang. Today we think in terms of creative destruction. Creativity disrupts and it innovates, it cleaves and it fills. There’s a unified opacity and thingy-ness to the world around us, and it all bears the traces of human engineering.

NO NEW THINGS

Everyone wants to know how a successful creator got from point A to point B. Many companies are willing to oblige, providing an origin story for every product. Eager entrepreneurs watch closely for clues to replicate success. Is it the graph-ruled Japanese notebook? The pour-over coffee? All of the details are spelled out ad nauseam, but in the end, the trailer has become longer than the feature we paid for.

Portrayals of the creative process formulate a managerial logic for the creative class. You can think about these displays as employee training: teaching you how to brainstorm, how to organize a workspace, and how to construct an environment that will let the creative juices freely flow. Documenting the home offices and personal spaces of creative producers can ease everyone into feeling less doomed in a world full of permalancers working between their apartments and incubators.

Creative production works under some hazy economics. Surplus doesn’t exist when every element can be commodified and any waste can be immediately repurposed (a bonus when you’re trying to be a responsible, ethical brand – neoliberal face-palm). It’s the “Nose to Tail” ethos as applied to creativity. It takes a process that (in the case of creative agencies and seed- round start-ups) uses resources to create intangible goods or creative capital and makes it look like it’s running off of its own fuels. With a blind eye to the pallets of Nespresso and bottled water being consumed, creativity can be made to seem like a self-perpetuating machine. The creative process becomes its own ecosystem, where creative energy is a renewable resource.

This is why any creative waste can end up becoming more valuable than the end product itself. Beyond sustainability, putting the waste on display vets the creative process’ authenticity. You can trace an idea back to the sprawling whiteboards of an incubator, or to the lacquered desk made of reclaimed wood in its founder’s swaggy apartment. Internally, this waste allows for everything to operate at an accelerated speed. There’s no need to stop and consider the next big thing when you can revisit the scraps knowing that every Post-It contains another possible app.

BLACK SWANS

The blue sky R&D era was about collective responsibility for innovation. The U.S. wrote the tax code in a way that basically capped executive salaries and offered subsidized credits to funnel that money into weirdo science projects. Some companies are still on this train – i.e., Google’s relentless quest to replicate the Star Trek computer – while others just let the money flood into CEO compensation packages, shareholder dividends, and Ireland. Using money to go where no man has gone before is no longer a foregone conclusion. It’s something that only grows out of a certain corporate ethos (or DARPA).

Steve Jobs dying freaked us all out for a variety of reasons. But a big one is that he intensified the suspicion that astronomic, era-defining success for a brand could only come from a single genius. He made everyone know, however briefly, that collaboration is a lie and that control cannot be networked or synthesized. But if innovation has to be centralized in order to thrive, that means it can die.

Innovation may have become an individual responsibility, but it still has collective consequences. This is why we want to imagine creative leaders as übermensch. The pro is that it satisfies our desire to have real-life heroes save us; the con is that it means our heroes can abandon us. Practically, both of these narratives benefit the creative leader.

Whereas the CEO provides accountability for risk by navigating the measurable reality that defines whether a business flounders or flourishes, the creative leader provides accountability for uncertainty. Trolls, cultural appropriation, extreme weather – these are the consumer influences that no big data model can credibly predict. The black swans lurking in the fog.

HEROES

In today’s economy, it pays to be a lot of people at once. The history of branding in the 20th century – the birth/death/adolescence of the corporate personality – is about making a group of people (the company) behave like a single person (the brand).

Conversely, the history of heroism is about making one person act with the strength of 10 men, or at least being impressed when someone gets close. Heroes rise to the occasion. It would’ve been way less cool for Hercules to clean all those stables and fuck all those bitches if he’d done it at a random time, or for no compelling reason. Heroes strike when the iron is hot.

The creative leader’s abilities can seem super-human. Like they have an X factor, a mutation for dealing with the sprawling complexity of global industrial civilization. We often perceive the X factor as an aura of personal cool. But it’s clear that the X factor that enables the creative leader is more form than content – and totally situational. The difference between X-Men and regular ol’ mutants is body armor and a supersonic stealth jet. To turn a freak into a superhero, all you have to do is accessorize.

In the same way, the difference between a speaker at TED and a crazy person screaming in the street is the platform they’re speaking from. That’s why creative leadership is priceless, but creative labor is worthless. Successful creative leaders are creatures of amplification. They’re uninterested in debating who “really built” it, and think the whole conversation is just another chicken-or-the-egg dispute, a concession to the stoner dorm logic of political debates.

Creative leaders are a timely negotiation of the individual and the group – a discrete configuration of the brand + the hero, the singular + the plural, the now + the what’s next. Their executive-creative vision conflates their personal will, the trajectory of a brand, and the thirst of an audience. They stand for that inconsistency with their creative genius; they vouch for it to whoever’s trying to keep the business on track. They rebrand caprice by performing it sexily to the public or staunchly to a board of directors. They know it’s their job to act like a mutant, even if in reality they might be a cyborg.

CREATIVE NONFICTION

It doesn’t matter to Airbnb whether you have an apartment; real success for a brand moves beyond the distribution of goods and into the distribution of ideas. (For more on this idea, download K-HOLE #2: ProLASTination from khole.net.) Recognition is as valuable as adoption. Haters are as valuable as followers. Success isn’t millions of followers, it’s envy – not just growing your existing userbase, but becoming a reference point for someone else’s.

Summon the creative leader. They’ve promised their genuinity, their intuition, and their personal experience (or lack thereof). Like any celebrity, they bring a personal audience. They’re given the privilege to come from one community and to work in many others, to connect a host of other niches to their niche. This mobility separates the creative leader from the creatives and gives the impression that their genius is irreplaceable. If it weren’t for the fact that there are lots of other creative leaders, equally adept at performing themselves, it might seem like they’ve beaten the system altogether.

The creative leader becomes the line through which the dots are connected – if not progress, then someone’s idea of progress. We get excited when designers are traded, like NBA players, to new studios. We watch them interpret the mission of a brand and challenge it. We actually witness the jump from A to B, from the brand before to the brand now. We don’t necessarily learn anything specific. But we do get a point of entry, and someone to idolize or blame.

Creative leaders keep the narrative of late capitalism popping by embodying progress. Without them, we face the existential reality that literally everything is beyond human control, that nothing really happens for a reason. How do you justify the transition to flat interface design? Or the deployment of an uncomfortably large screen size for a mobile phone? Or the exploi- tation of a step team to spice up a runway collection? Recognizing that there might be too much going on to explain “why exactly,” creative leaders offer themselves as the answer to literally every other question.