In Memoriam: TABEA BLUMENSCHEIN (August 11, 1952 – March 2, 2020)

This week marks the one-year anniversary of the death of Tabea Blumenschein, maven and muse of the West Berlin artistic underground. In the following obituary, originally published last year in the German weekly TIP, Wolfgang Müller – artist, author, chronicler of the West Berlin subculture, and our creative partner for the 032c RTW Spring/Summer 2021 collection – bids farewell to his collaborator in Die Tödliche Doris (1982 – 1987), and his friend until the end.

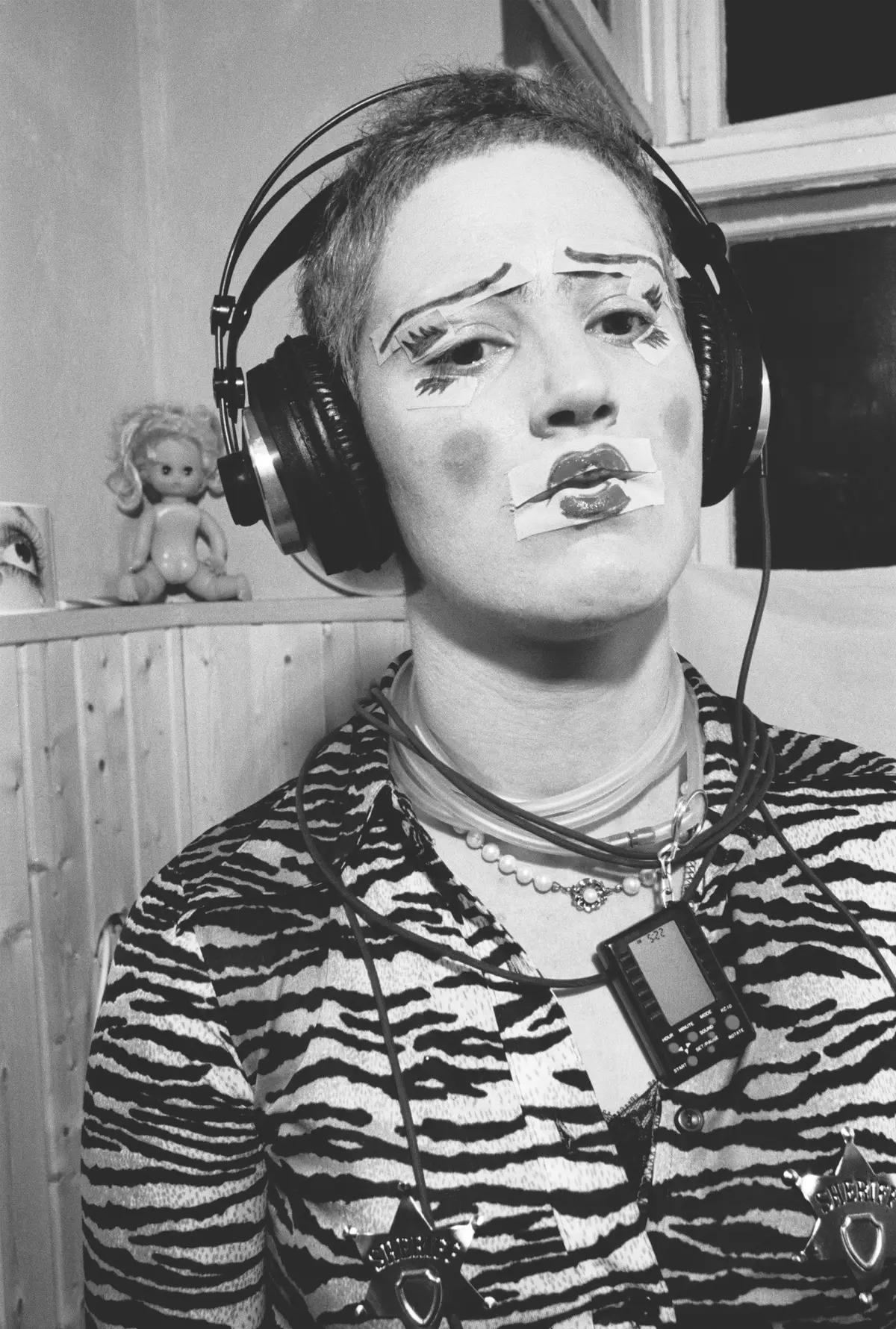

Shortly after arriving in West Berlin from the West German provinces in January 1979, I was offered a coveted job at a café called Anderes Ufer. Just two houses down Hauptstraße was the “Altbau” apartment David Bowie had lived in since 1976. Bowie ignited the pre-queer spirit that paved the way for city’s first openly gay café. Anderes Ufer was where Gudrun Gut got to know Blixa Bargeld, for example, and I – still a waiter – met Tabea Blumenschein. Tabea, a figure of breathtaking beauty, an apparition, a true Hollywood femme, lived just around the corner, on Schöneberg’s Erdmannstraße, in a huge old apartment. Thanks to her role in Ulrike Ottinger’s Ticket of No Return (1979), she was already a star of the West Berlin scene.

Painter Salomé, Naked in Barbed Wire

It is hard to imagine, but in those days lesbian and gay bars were locked and shuttered, and you could only get in by ringing the bell. Ours was the first place with open doors and windows. After opening, Anderes Ufer immediately became a meeting place for West Berlin bohemians. In one performance there, the painter known as Salomé curled himself up in barbed wire, naked. He wanted to make the suffering of gays visible on his own body. Watching from one of the café’s marble tables, Tabea Blumenschein – not suffering at all –lustfully put her hand up the leather skirt of her beautiful companion, Isabelle.

Looking back, it’s clear that Tabea was the first appearance of queer feminist punk, a proto-riot grrrl decades before its later expression. “I don’t make myself ugly to displease men,” Tabea said, “but beautiful to please women.” In her fashion drawings for the German edition of Warhol’s Interview she ignored convention: her models had prosthetic legs, were too fat or too thin, trans, or otherwise beyond classical norms.

Never Strategic

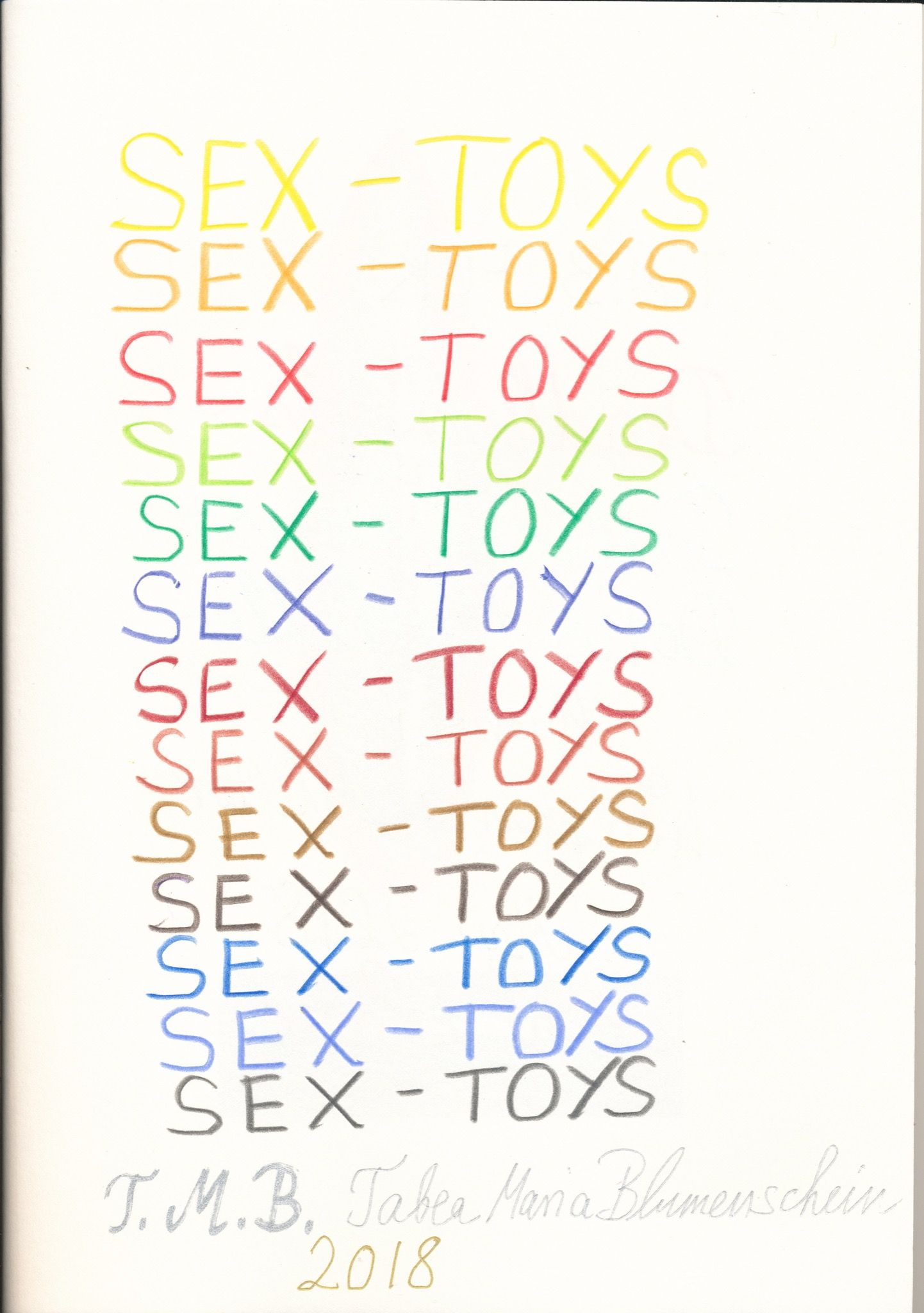

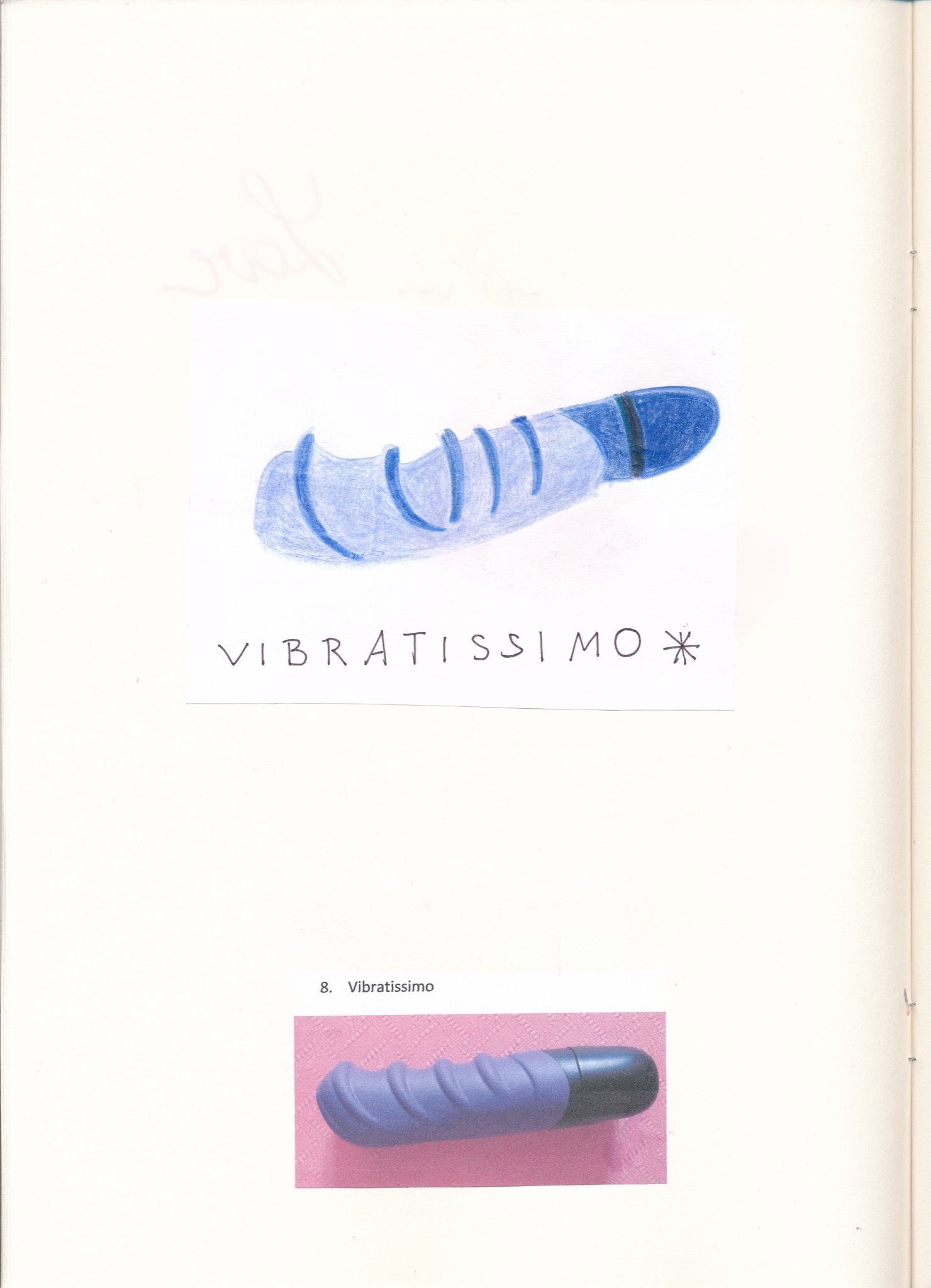

When I founded Die Tödliche Doris in 1980 with my fellow UdK student Nikolaus Utermöhlen, Tabea immediately agreed to participate – but only when she had the time and inclination. When we were invited to Japan in 1988, Tabea declined: “Japan is a little too far away for me. Plus I don’t know anyone there.” I later learned that Tabea had a lot of fans in Japan. Masanori Akashi told me as much in Tokyo just this February, when he heard the latest Die Tödliche Doris album, Reenactment – complete with its sex-toy sounds and, as the Spiegel wrote, “extremely nicely drawn device portraits” by Tabea Blumenschein.

Tabea was full of incredibly original, defiant ideas – until the very end – but she wasn’t a bit ambitious, determined, or vain. She never used her talent strategically. She was not interested in money or in capitalizing on the image she had back in the day.

Pictured above: For the 2019 re-release of Die Tödliche Doris’ first album, Das typische Ding, which included 1-minute recordings of 31 different vibrators, Blumenschein created playful drawings of each device, inspired by product reviews published by feminist Queer theorist Katrin Kämpf. Read more here.

Kippenbergers Taken Out with the Trash

“Only you could go from a five-room apartment in Schöneberg to sleeping in a homeless shelter on a cot,” Martin Kippenberger once told Tabea when she came straight from the shelter to meet up with him at Paris Bar, as she related in one of the rare interviews she gave after 1990. She happened to have thrown away some of Kippenberger’s works just a few months earlier: “I simply had no more room,” she said. Anyone else would have regretted the purge – and the loss of the apartment that could have been purchased with the proceeds had the paintings been sold – but Tabea never gave it another thought from the Marzahn bedsit she would eventually occupy. “Whether you live in Zehlendorf, Schöneberg, or Marzahn,” she said, “intelligence remains the same.” Evidently, so do creativity and talent.

I am very sad, my beloved sweet elf. Sleep well.