Fitzcarraldo Editions: The Biggest Little Press in the World

|Shane Anderson

FITZCARRALDO EDITIONS is the biggest sensation in publishing in decades. Based in the Deptford district of London, the independent house has published four winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature and counting. But what makes the press so successful outside traditional book circles? Is it their refined literary taste or their sleek, distinctive books that act as a cultural signifier?

Photography: Ray O'Meara

This story is not about branding, but maybe it should be, was the first thought that came to me as I walked out of the offices of Fitzcarraldo Editions, the independent publishing house that has taken the literary world by storm. Although the last 12 words of the previous sentence could induce shudders in some readers for their echoes of clickbait articles and listicles, there may be no better way to describe what publisher Jacques Testard has achieved since the French native founded the London house as a one-man operation in 2014. During the maiden decade of the press, Testard and the other eight employees now on his team published four winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature (Svetlana Alexievich in 2015, Olga Tokarczuk in 2018, Annie Ernaux in 2022, and Jon Fosse in 2023), and their authors are fixtures on the longlists and shortlists of all the most prestigious British and international awards, some of which they have received. As of last year, the house has also sold more than one million print units, and every title, with but one exception, has sold at least 1,000 copies. For reference, the average sales per unit for a new work of literary fiction is 250 copies in the United Kingdom. These are no small feats for a small team that had a turnover of just under two million pounds in 2023, but their greatest triumph to date might be that they have made “challenging literature chic,” as a recent New Yorker profile puts it.

But why chic? And how come I get compliments for my good taste in literature when I have a Fitzcarraldo book poking out of my jacket pocket in a hotel lobby and the title isn’t even visible? The answer probably has to do with branding, I thought as I made my way down a flight of stairs inside the Fuel Tank building, which is home to their 67-square meter open-plan space that looks exactly how you might expect an independent publishing house’s office to look: copies of their books line bookshelves with emaciated plants atop them; a round meeting table is covered in printing dummies and advance reading copies; Post-its with the upcoming publishing schedule dot a wall; desks with computers face one another; and art is scattered about, including a John Waters blow-up doll and a Giles Round watercolor of Paul B. Preciado’s book from Fitzcarraldo.

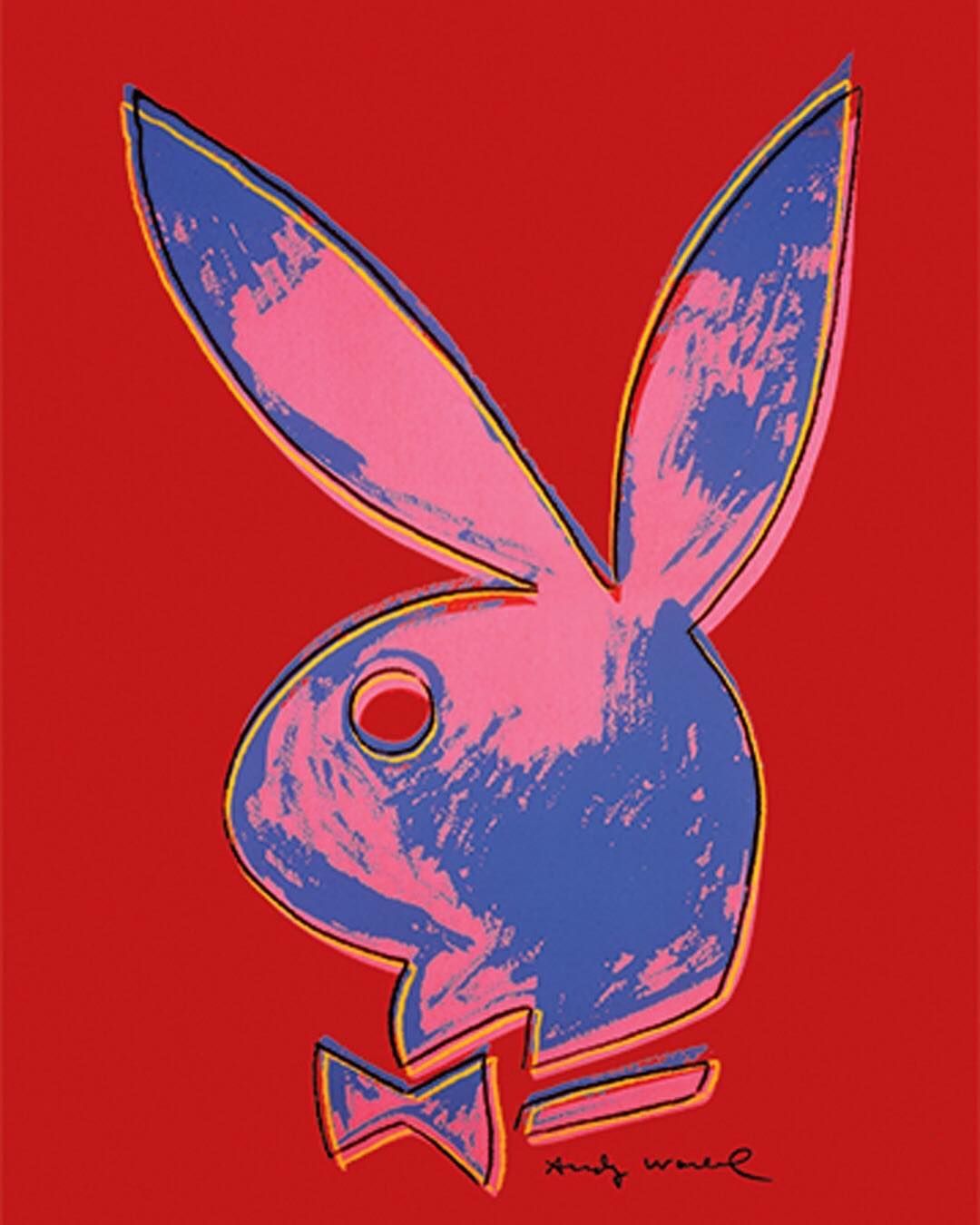

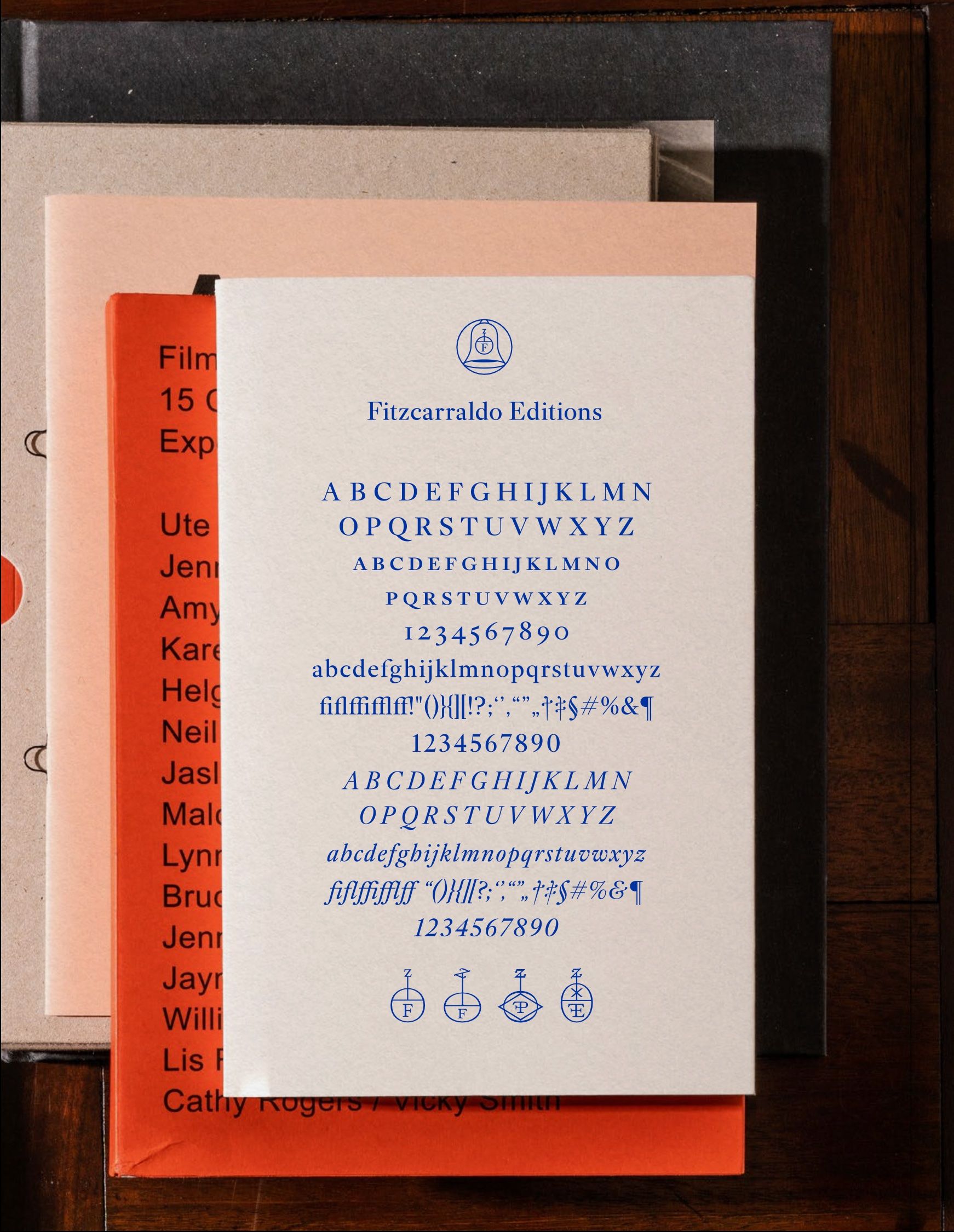

Like Apple products, Fitzcarraldo books are immediately identifiable. Minimalist, with a two-tone design, the covers of their fiction titles are Klein International Blue, with the names of the work and the author in white type, whereas the covers of nonfiction titles are white, with the names of the work and the author in Klein International Blue. Both lines are flapped paperbacks – and each volume has a synopsis on the back, as well as a single endorsement from an esteemed colleague. The text is centered on the front cover and justified on the back, and all of it is printed in a clean, elegant serif font designed by art director Ray O’Meara. It’s called Fitzcarraldo. The front of each book, whether fiction or nonfiction, bears a blind stamp colophon: a bell in a circle with the letters F and Z, marks that reference the history of printing. These design features go against the grain of contemporary publishing strategies, wherein each book is treated as a world unto itself. To get the book’s point across without words, titles at other presses receive some unique image or illustration on the front, with the title smeared in whatever font the marketing team currently loves (where loves means approved by market analysis). By keeping things simple and consistent, Fitzcarraldo Editions recalls other famous presses, especially the French Éditions de Minuit and the German Suhrkamp Verlag, while remaining distinct.

To dare to mention branding in independent publishing is, if not a sin, at least something frowned upon. This distaste may be out of arrogance – “We’re a publishing house, not a shoe company,” one publisher once told me – or, more nobly, out of anticapitalist sentiments. But the latter is difficult to defend if the aim is to create a lasting venture, one in which orders have to be fulfilled, schedules have to be met, and editors, authors, translators, and rent have to be paid. (“Other houses don’t lean into brand identity, and that’s why publishing is dying,” said one Fitzcarraldo author who prefers to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of this matter.)

As with Aēsop and its old-timey apothecary vibes, Fitzcarraldo has carved out a quiet seeming niche in a market that shouts to get attention. And the publisher has done so in part by exploiting industry biases. In the United States, only three percent of books published annually are translated from other languages, and some sources say the number is closer to 0.7 percent if we limit ourselves to literary fiction and poetry. Theories to explain this low number include the money it costs to pay for translation, the limited number of US-American editors who speak another language, and the feeling that “we have enough good writers at home.” Similar numbers can be seen in the British market, which suggests that the sentiments are alike. Compare those numbers with Fitzcarraldo’s, though – roughly half of whose titles are in translation – and you see how Les Bleus et Les Blancs have been free to mine mother lodes from other markets before testing the waters in English with little to no competition.

Mixed metaphors aside, such writers as Tokarczuk, Fosse, and Alexievich all had large followings in places such as France and Germany, as well as in their home countries, yet had scant representation in the English-speaking world. The Belarusian Alexievich’s oral history of the Soviet Union’s collapse, Secondhand Time (2013), for instance, had already sold hundreds of thousands of copies in France when Testard inquired about the book’s rights, before the 2014 Frankfurt Book Fair. He was denied by Alexievich’s agent at first because Testard then had only two books under his belt. Testard made a new offer “without much hope,” as he told Granta, but it turned out to be the only offer from an English language publishing house, and Alexievich’s camp “agreed to a deal for the book a few weeks later.” Alexievich would go on to win the Nobel Prize in 2015, and to date that book, in Bela Shayevich’s translation, is in its 13th printing. Similar stories could be told of Tokarczuk. Testard acquired a couple of her books in 2016. Today, Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, is Fitzcarraldo’s best-selling title, with more than 150,000 print copies. Beneath the names of the work and the author, later editions feature the tagline “Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature.” Some readers of the foregoing might question Fitzcarraldo’s sincerity, chalking up its tactics to marketing gimmicks. And some readers I know have even been so mistrustful of the press as to suggest that Testard must be bribing the Nobel academy (“Their books are basically written for the Swedish bourgeoise,” another publisher once told me). I strongly disagree. Not only do the books suggest a vision, but when I spoke to three members of the team, I was struck by their politics, ideals, rigor, taste, competence, and presence. Testard, editor Joely Day, and publicity director Clare Bogen were all soft spoken yet sure of themselves. Everything they said felt sincere, driven. And from everything I learned in the hours we spent together, it seems safe to assume that the six other members of the team are no different – which is to say that this story is not about branding, or not only.

Like Apple products, Fitzcarraldo books are immediately identifiable.

Klaus Kinski in Werner Herzog's Fitzcarraldo (1982), still in disbelief that a steamboat was dragged over a mountain.

The name that Testard chose for the press refers to Werner Herzog’s film Fitzcarraldo (1982), about an opera fanatic and would-be rubber baron who dreams of building an opera house in the middle of the Amazonian jungle. One of the most iconic scenes in the film shows Fitzcarraldo, played by Klaus Kinski, order a steamboat to be hauled over a mountain – something that Herzog actually had done on location, in real life. The entanglement of this dream, this scene, and the meta-level of the real-life filming being even more batshit crazy than the movie have all led to the term Fitzcarraldo becoming a catchword for quixotic endeavors driven by relentless determination. Testard admitted to The New York Times that christening the press with the obsessive film’s title “was a not very subtle metaphor on the stupidity of setting up a publishing house.” Why stupid? Because publishing often “feels like you’re just digging a hole in the ground and chucking money into it.” (Another publisher once told me: How do you make a million dollars in publishing? Start with five.)

Embracing the hubris and future bankruptcy of becoming a publisher, Testard pulled his best Kinski impersonation with the release of the house’s first book. Translated by Charlotte Mandell, Mathias Énard’s Zone (2014) is a 521-page stream-of-consciousness tale about a French Intelligence Service agent who is on a 521-kilometer journey to the Vatican to deliver a report on various war crimes committed in “the Zone.” Told in a single breathless sentence by a narrator amped up on amphetamines, the novel is as much about the political violence he has witnessed as it is about his various random memories. Fitzcarraldo’s website describes Zone as “an Iliad for our time,” which, even if some readers agree that the book is both epic in scope and very much about war, is just a little “Fitzcarraldian” in its bravado, no?

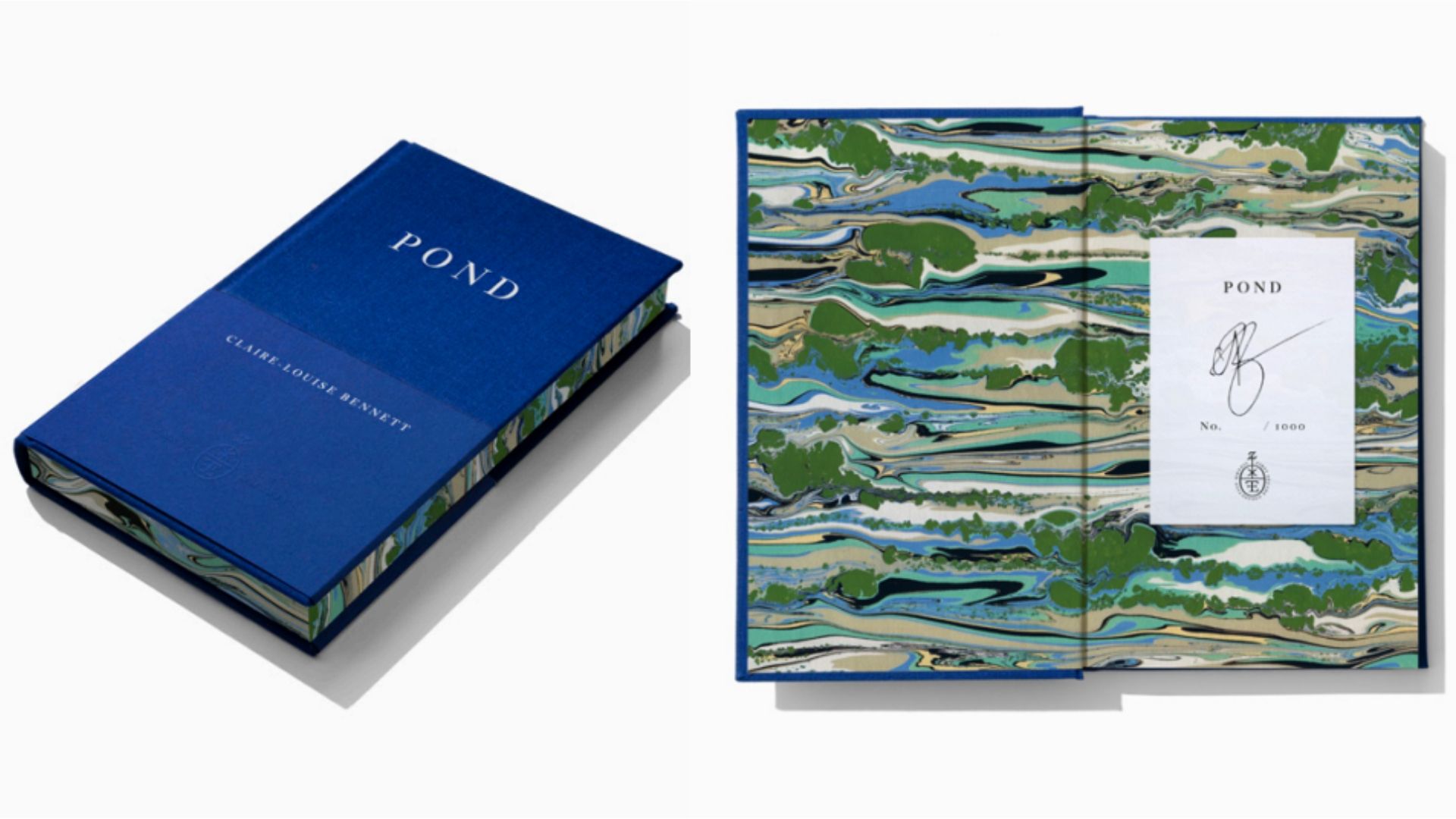

Serving as a wild and daring opening statement, Zone demonstrated that Testard’s aim was to “take risks and publish ambitious, innovative contemporary writing of a very high literary quality.” What is more, Testard hoped to show that “every [Fitzcarraldo] book that a reader might pick up is going to feel and read a bit differently than what other publishers are doing.” The early catalogue probed these lofty aims in both fiction and nonfiction titles, but the collective thrust of the first seven books could be likened to a chick stabbing through its shell with its beak in comparison to the maul-like intensity of the writing in the eighth book, Pond (2015), by Claire-Louise Bennett.

With its savage, swarming magic, Pond served as a watershed moment for the press. This collection of short stories details the life of a woman living on her own outside Galway, Ireland, where she contemplates things such as tomato paste. Although this summary might make the work sound banal, in Bennett’s hands, these everyday items and situations are at times profound, at other times hilarious, but often they are both. Writing about this “truly stunning debut,” The Guardian suggests that Bennett aims at “nothing short of a re-enchantment of the world. Everyday objects take on a luminous, almost numinous, quality through the examination of what Emerson called ‘the low, the common, the near’ or the exploration of Georges Perec’s ‘infra-ordinary’ – a quest for the quotidian.”

The First Decade Collection edition of Pond.

Exhibit A, “First Thing” from Pond:

The ratcatcher woke me. I knew he was coming, but I’d had three overflowing beers the night before and I’d slept through the rat and I wanted to go on sleeping.

Go on sleeping through the rising birds and through the horses walking up the hill and through the four cows rearranging themselves and through the dog that follows the horses on their way down the hill and through the cat here and there and through the fox stopping and starting on the driveway and through the donkey standing, but the ratcatcher woke me and down the stairs I came and made us both coffees right away. And because I wasn’t really here I didn’t yet know how I like things, so I put two sugars and milk into my coffee, because that’s how the ratcatcher takes his.

Without delving too deep into a reading, the rhythm and repetition and their dizzying effect parallel the discombobulated state of the narrator, whose daily ritual of making coffee has become foreign because of the ratcatcher. The writing here is reminiscent of prose poems by contemporary poets who look at seemingly ordinary occurrences and find larger truths within them, but what I like about Bennett is that the conclusion is open. She’s not trying to convince us of anything. Is this a story about patriarchy? Or someone who has lost awareness of her wants and needs? Shorter scenes like this one contrast with longer passages wherein we are witness to a mind finding its way through the day and through language and through being alone.

While Testard and I sat at their large round table in what makes up the meeting-room portion of the open-floor layout, he suggested that Pond served as a “gateway drug” into the Fitzcarraldo world for half the team members. Confirming this observation, editor Day, who often gave very intricate answers to my questions about manuscripts, kept things very simple with Pond. In her precise British English, she noted, “It really blew me away. It was such a singular read. And I guess that kind of experience or feeling for a book is what I will always be looking for.” As for publicity director Bogen – who has a recognizable American accent despite being half Kiwi and living and working in the United Kingdom for a decade and a half – she can still recite whole passages from the book, even though she has not read it in years. Pond, Bogen said, “has affected me in ways only a favorite book can.” She also mentioned that, even after 14 printings, Pond still sits atop the London Review Bookshop’s bestseller list almost every week. (When I visited the store the next day, I found not only Pond on the bestseller shelf, as predicted, but also a handwritten endorsement by a bookstore employee named Gayle: “Not a day goes past that I don’t shake a fist at the sky and cry in despair ‘When will CLAIRE-LOUISE BENNETT publish something new? Until my cries are answered, I’ll make do with re-reading POND, Bennett’s wildly brilliant and totally unique collection of stories following one woman living alone in the Irish countryside.”)

You might assume from all this adulation that Pond was a great success from the beginning. That people were lining up to have their skin Sharpied at readings and that 2016 had an uptick of babies being named Claire-Louise. But as with many cult artifacts, finding an audience took time. The second reading Bennett ever did in promotion of the book was with Brian Dillon at the Burgess Foundation in Manchester, and only six people were in attendance. Testard and Bennett “and sometimes her brother” nevertheless toured the country, doing more than 20 events in something Testard described as not “Gonzo publicity exactly” but without ever revealing how it was not or what it was instead. Later he clarified, “Umm, it was just a series of events …?” With time, Bennett’s charismatic personality and the strength of the words slowly spread like mycelium throughout the literature-loving underbrush. Now, the abundance of admirers is as hard to deny as the book’s hallucinatory prose. Recently, Bennett and Dillon were on stage for an anniversary event, which sold out within a day of being announced. Fans with well-worn copies queued.

Watching Bennett’s audience steadily grow through events cemented their significance in Testard’s mind. He realized that you had to go to the bookstores and community centers and wherever else readers might be hiding, and that it was equally vital that someone from the press be in attendance as a representative. “At the beginning,” Testard said, “it was just me publishing six books a year, and I would systematically go to every event with the authors as the list grew.” Nowadays, at least one of the nine staff members is present for a reading or presentation, regardless of whether it’s in London or Paris, Durham or Belper, as being on hand for events is part of the company’s “mission to indoctrinate” the public. This approach is almost unthinkable in the context of larger houses, Bogen told me, except for authors with higher profiles. Elsewhere, “You just get handed your list of titles” as a member of the publicity department, and then you fire off emails into the void of potential reviewers. At Fitzcarraldo, however, Bogen is involved in every stage of a book’s life, and the environment is collaborative. Together, the team does its best to help one another help the author and/or translator shape their vision and to get it to as many people as possible. According to all three of them, the author takes precedence at the press, which is obvious – but not how other presses normally do things. The Fitzcarraldo team takes this notion so seriously that DEFCON 3 is activated whenever a new manuscript by a Fitzcarraldo author lands in their inbox. Testard: “An author is never as vulnerable than at the point where they send a book out to be read, which is why I always try to read a new book by someone we already publish as quickly as possible.”

Photo: Ray O'Meara

Exhibit B, Branding: A Case Study

The use of Klein International Blue is influenced by the French Modernist artist Yves Klein as well as the Venetian obsession with the pigment ultramarine during the Renaissance. With their restrained color code of white and blue, Fitzcarraldo Editions has a modern clarity and simplicity that creates a space of concentrated silence, where the house, title, and author are presented as equals.

When Fitzcarraldo Editions launched, they wanted the titles to feel both classical and contemporary. Translating this into tactility, the team chose premium fine papers and uncoated flapped card covers (which also keeps the covers from curling) and avoided the use of plastic coatings. While the books were conceived as design objects to be collected, their white nonfiction covers’ propensity to staining and the blue titles’ wearing at the spine are telling of how the books are read and shared and accumulate the traces of the reading experience.

Once the press decided on the name Fitzcarraldo Editions, O’Meara looked at several scenes from the Werner Herzog film for inspiration for the colophon – but not, surprisingly, at the mountain boat scene. One moment that seemed emblematic was Sweeney Fitzgerald’s rant from the bell tower. Having explored variants of towers and bells, he landed on a roundel with a bell inside it, adding “F” and “z” as a reference to historical printer’s marks. The classics, trade, poetry, and First Decade Collection each has its own iteration of the emblem. With the need to create something less monumental for the trade editions, the house maintained its colorways and presented titles in large lowercase, elaborating their pared-back look but with less formality for the sake of trade materials and printing.

The Fitzcarraldo typeface, designed by O’Meara, references an eclectic mix of old style, transitional, and modern typefaces while not sitting neatly in any one category. In layout, the contrast of the margins’ white space and the dark “inked” text block adds to the severity of the house aesthetic.

On Instagram, Fitzcarraldo recently announced that they will publish Claire-Louise Bennett's new novel, BIG KISS, BYE-BYE, on 9 October 2025. Image courtesy of Instagram.com/fitzcarraldoeditions

As for all those other writers who send their manuscripts in droves, they have to make do with biting their fingernails. Because of Fitzcarraldo’s dedication to its authors, Day can only manage to read new manuscripts on the weekend, and Testard, father to an 11-month-old daughter, squeezes in some pages between family time and sleep. But such dribs of time are no match against the onslaught they face. Day was unsure how many pitches she receives, but Testard estimated he fields at least five a day, and that includes neither the general info@ account, nor what associate publisher Tamara Sampey-Jawad – who couldn’t join us for the meeting – deals with. When I asked what made certain manuscripts from the slush pile stand out, Testard said that it’s better for a new author’s title to “have echoes or affinities with work by another Fitzcarraldo author,” rather than the alternative. In effect, Fitzcarraldo is creating its own universe in which everything is connected and nothing is random.

Here, Testard takes inspiration from Roberto Calasso (1941–2021), the longtime publisher of Adelphi Edizioni. Founded in Milan in 1962, Adelphi Editions (ahem, Edizioni) became famous for its dedication to high-quality literature and for often focusing on works that were either overlooked or underappreciated in the mainstream literary world. (Sound familiar?) In addition to being an editor, Calasso was also a gifted writer about mythology, among other things, and his titles include the collection of essays The Art of the Publisher (2015), which, according to Testard, puts forward the thesis that “a literary publishing house obviously exists to publish singular works of art, but added up together, each individual book contributes to this bigger work of art, the publishing house, where all the books are connected in some way.” Testard continued, “I guess another way of thinking about the catalogue as a work of art is to think of it as a constellation.”

To my mind, Fitzcarraldo is more like a cluster of constellations, creating a tableau in the night sky. There’s Hydra the serpent, with all the writers of slithering stream of consciousness (including Fosse, Énard, Rainald Goetz, and Fernanda Melchor), and the cup on Hydra’s back that symbolizes accountability (including Adania Shibli, Eula Biss, and Maria Tumarkin), to name but two. Bogen also directed me to another constellation, namely the one of chewy language, where writers such as Claire-Louise Bennett and Janet Frame demonstrate “the same attention to the way words sound on the page.” Frame is now being published in the new Fitzcarraldo Editions Classics line, where the house is looking back in time through the affinities and influences of the authors they already publish.

When I told Testard that another constellation I noticed was spirituality, he answered that I was the first person to ever suggest such a thing. Slightly taken aback, I backed it up with Fosse’s Septology (2019), translated by Damion Searls, which investigates the faith of a painter, and Tokarczuk’s The Books of Jacob (2014), translated by Jennifer Croft, which, very roughly, is about creating a new religion. I was about to bring in Patrick Langley’s The Variations (2023), but before I could, Testard suggested that the overriding theme in the list is the “weight of the past on the present”; it’s memory.

And, in fact, the Fitzcarraldo universe is teeming with it. You can find memory in Simon Critchley, Annie Ernaux, Kirsty Bell, Ian Penman, Mathias Énard, Maria Stepanova (who literally has a book called In Memory of Memory [2017], translated by Sasha Dugdale), Adania Shibli, and on and on and on. It takes many different shapes and forms, but one of the most daring memory projects Fitzcarraldo has published to date is Rombo (2022), by the German writer Esther Kinsky. On the surface, the book looks at how two earthquakes that ripped through northeastern Italy had an impact on seven inhabitants of a remote mountain village, but the book’s translator, Caroline Schmidt, told me that “Rombo is also about the ways the earth remembers and forgets.”

"I want to stay independent forever."

Publisher Jacques Testard making a deal at the Frankfurter Hof hotel during the 2024 Frankfurt Book Fair. Photo: Shane Anderson

It should be stated that Testard’s interest in memory preceded the press. He completed a master’s in history at Oxford, where he conducted research on collective memory. After he sat through a seminar on the memorial bells and fountains of Oxfordshire from 1847 to 1857, though, he threw in the towel and went into publishing – first in magazines, now in books. And although the dullness of those Oxfordshire bells may have evoked only muted heaviness, they are nevertheless echoed in the colophon of his press, in the bell within the circle – which also is another reference to the Herzog movie, as Kinski’s Fitzcarraldo rages atop a bell tower, demanding that an opera house be built in a small Amazonian town.

Despite being previously shut down, I wagered another constellation, guesstimating that politics is important. Agreeing, Testard started with the rote “all publishing is political” before sounding bored with the answer himself, and noting instead that Alaa Abd El-Fattah’s You Have Not Yet Been Defeated (2021), translated by an anonymous collective, will be republished in Fitzcarraldo’s new First Decade Collection. When I asked why Testard is including the writings of the political prisoner alongside the Nobel Prize winners and Claire-Louise Bennett, as well as Kate Briggs, Joshua Cohen, Brian Dillon, and Fernanda Melchor – all writers who have brought the press accolades – Testard suggested that You Have Not Yet Been Defeated was “one of those moments when the constellation suddenly expanded.”

Which the press is doing now. In addition to rolling out the First Decade Collection, Fitzcarraldo Editions will commence publishing poetry under the guidance of Rachael Allen, the company’s new poetry editor, at the start of 2025. The book design will vary; some volumes will have a slightly wider format to accommodate the occasional long line of poetry, and the covers will feature black text on white background with a Klein International Blue frame, which perfectly parallels the blend of fiction and nonfiction that is poetry. O’Meara designed a new colophon, just as he did for the Classics and trade paperback lines, where he removed the bell and made the printer’s marks the focal points. The press now employs five different colophons, one per series design.

When I asked Testard whether he could imagine ever adding kids’ books to the catalogue, he suggested that he does not feel the need to, and that he is discovering plenty of good titles for his daughter from other presses. For him, the press is reaching its perfect iteration – poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and classics – and he is following the lead of New Directions’ founder James Laughlin, whose will was rumored to have dictated that New Directions, an independent publishing house based in New York, should never have a 13th employee, “because as soon as you do, you have to start publishing books for commercial reasons.” Testard then admitted that this story isn’t true, that Laughlin’s will didn’t include this demand, but that the ethos is what matters. “It’s important for us to remain small enough to never have to publish a book for commercial reasons and to be able to keep publishing books because we think they’re really good.” Has he ever thought about becoming part of a larger conglomerate? “Never. I want to stay independent forever.” But have they ever approached him? “There have been a few lunches.” But the answer has always remained no? “I’m not interested in selling the company. I like my job.” And maybe that’s the real story. Fitzcarraldo is not what it is because of branding and not because they publish excellent books, either – or, not only. Testard likes pushing the boat over the mountain. If he didn’t, there’d be no story.

Credits

- Text: Shane Anderson