Fallout! How Russian art confronted Chernobyl

Mushroom clouds from the Soviet atomic age have outlasted the Soviet system itself, and cast a long shadow over the Russian art world, writes THE CALVERT JOURNAL’S Jacob Dreyer.

If Russian art, past and present, has often been addressed to a mystical and imagined homeland, the sense of alienation caused by urbanism, technology, and mass society has been all the more acute. For a generation of Russian artists, atomic apocalypse was a metaphor for the emptiness beneath the banality of everyday life. The explosions at Chernobyl, 30 years ago today, threw these into ultra-bright relief, though artists questioned the doomsday devices employed by the state in the years before that fateful morning in 1986.

With a long history of millenarian doomsday predictions, the atomic threat and the artworks it motivated allowed for an update of very old – and perhaps very Russian – fatalism, we take a look at the atom bomb in Russian art history, before and after the explosion.

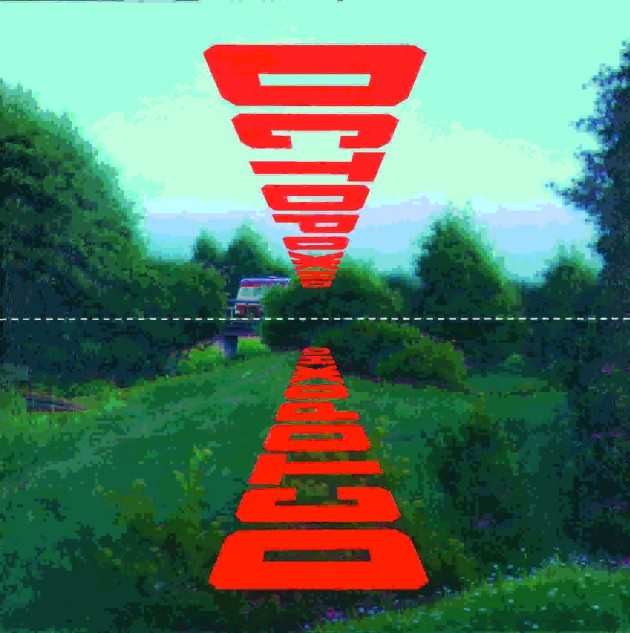

For some artists, technology has the power to sever our bond with the homeland- a preoccupation which came to a head in the era of the nuclear threat. Consider conceptualist Erik Bulatov’s Caution, one of his best-known works. A bucolic landscape; a flowing river — this is the motherland we all carry in our minds, a platonic ideal, overlaid by a warning which is vague and brief. There’s something wrong here, Bulatov is saying: not all is what it seems. Here, atomic weapons are a synecdoche for distrust of the modern world.

While Ilya Kabakov was famously memorializing the beauty of decaying Soviet interiors, Boris Orlov was depicting the external projections of might- and the ways that the regime took nuclear weapons as the core of its legitimacy- by literally wrapping up bombs and missiles in the ideological symbols of the regime.

Public space in the former Soviet Union is full of great murals, and this one is one of the most striking of them all –analogous to the work of Diego Rivera or medieval Russian icon painting, it represents the whole society. The atomic explosion in the top right corner of the mural is more than an expression of nuclear threat: it is a critique of modernity itself. In this social cycle, the atomic bomb is a signifier for judgment day.

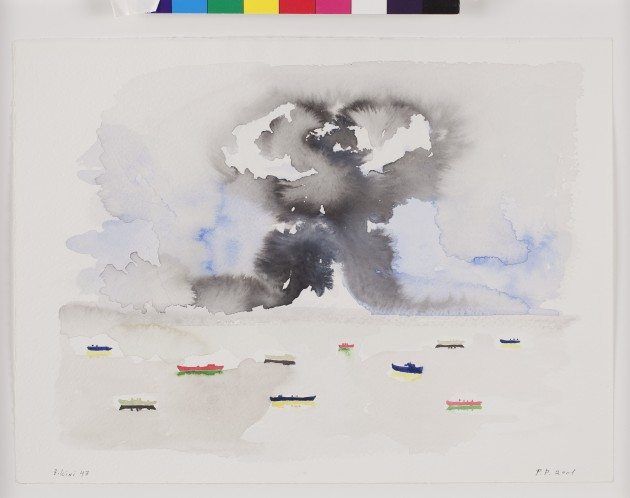

Pepperstein is a man whose life story encapsulates recent Russian history – coming from an artistic family (his father is currently enjoying a retrospective at Moscow’s Garage Museum), he is an avant-garde painter, ex-squatter, and now the subject of a glowing Vogue profile. In this dreamy series of watercolors, which eulogize the atomic testing on the Bikini Atoll, Pepperstein offers a light, dreamy view of the ominous grimness of the subject.

Tishkov is an artist from the region of Chelyabinsk: a place rich in folklore and traditions, and also a place which suffered one of the worst atomic explosions in history, in 1957, during the development of the Soviet Bomb. His mother presented him with this traditional doily handicraft in the shape of a mushroom cloud, an indication of how atomic preoccupations reached not only urban sophisticates, but deep into the forests and villages of the countryside.

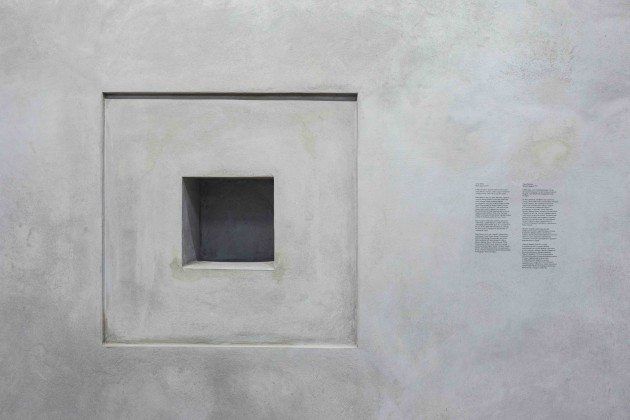

The greatest and most direct response in Russia to the nuclear aftermath, however, might be American artist Taryn Simon’s work Black Square XVII, part of her current show at Garage in Moscow and the fruit of a collaboration with ROSATOM – the Russian nuclear agency whose Soviet incarnation built Chernobyl. Simon created a void in the gallery wall of the same dimensions of a piece of nuclear waste that she co-created with ROSATOM. The cube of nuclear waste, buried in a secure site outside of Moscow, won’t be visible by humans for 999 years, a timeframe that forces us to ask if anybody will still be around to see it at that time. Art continues to ask painful questions of whether our technological society is capable of controlling the forces it has unleashed.