What is AI? Matteo Pasquinelli

|SHANE ANDERSON

Usually, it's understood as a simulation of human intelligence by machines. The philosopher Matteo Pasquinelli argues, however, that AI is shaped by the intelligence of labor and social relations. In 032c Issue #44 (Summer 2024), he talked to Shane Anderson.

Gustave Doré, The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri, Inferno, Canto 28: The Severed Head of Bertrand de Born Speaks to Dante, 1885

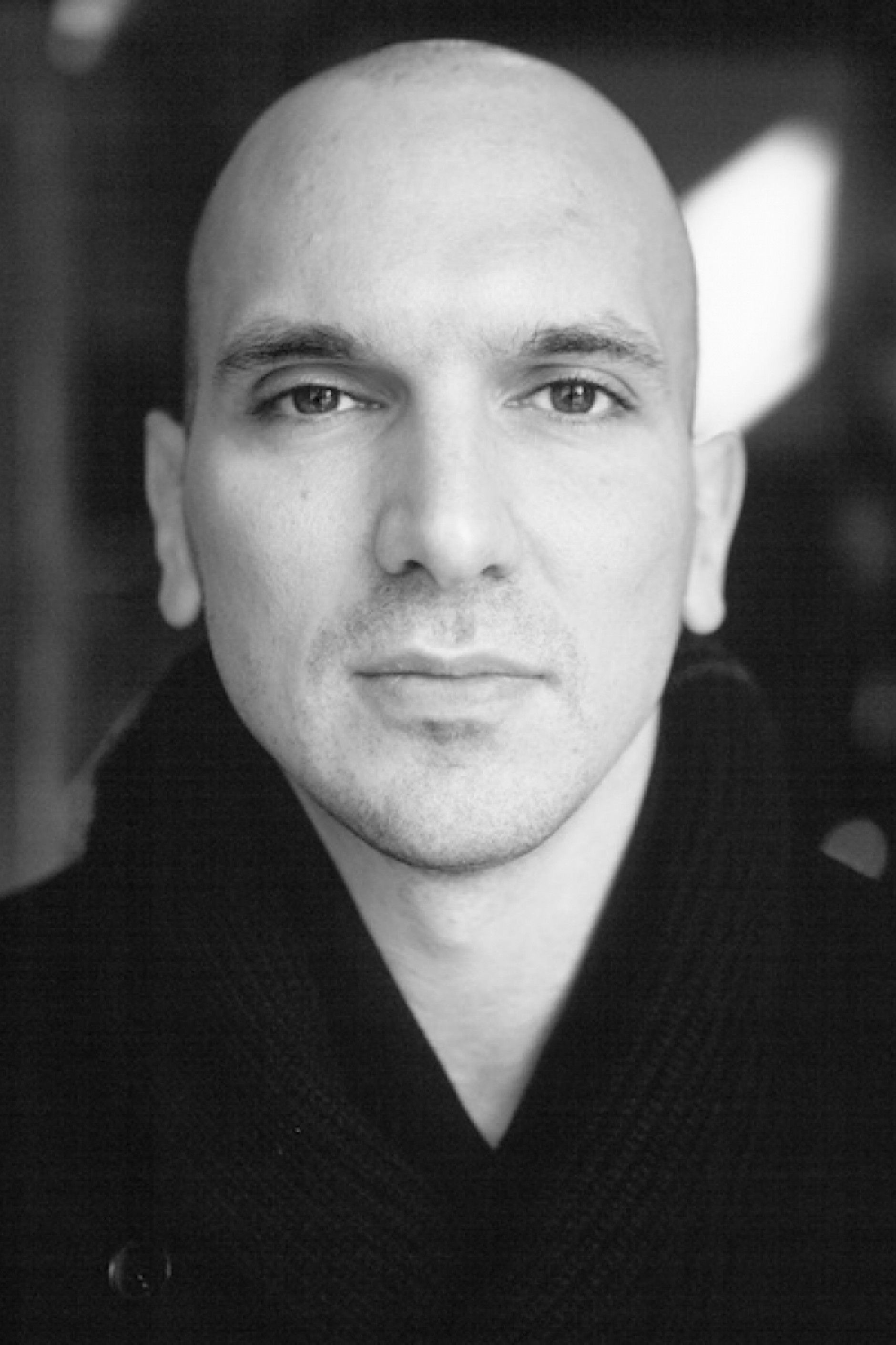

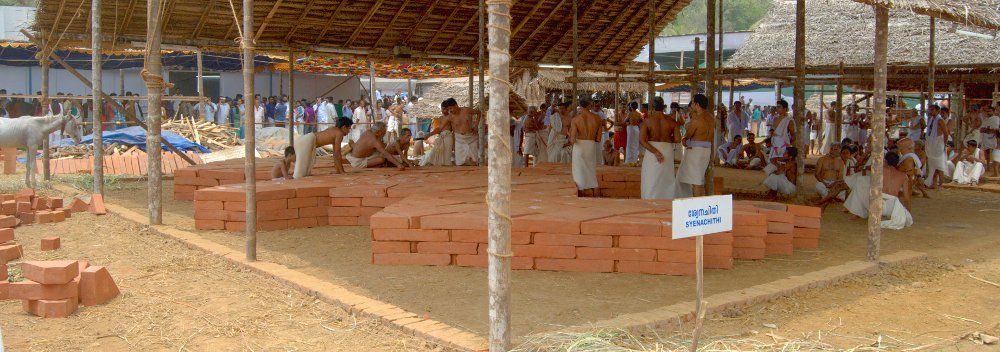

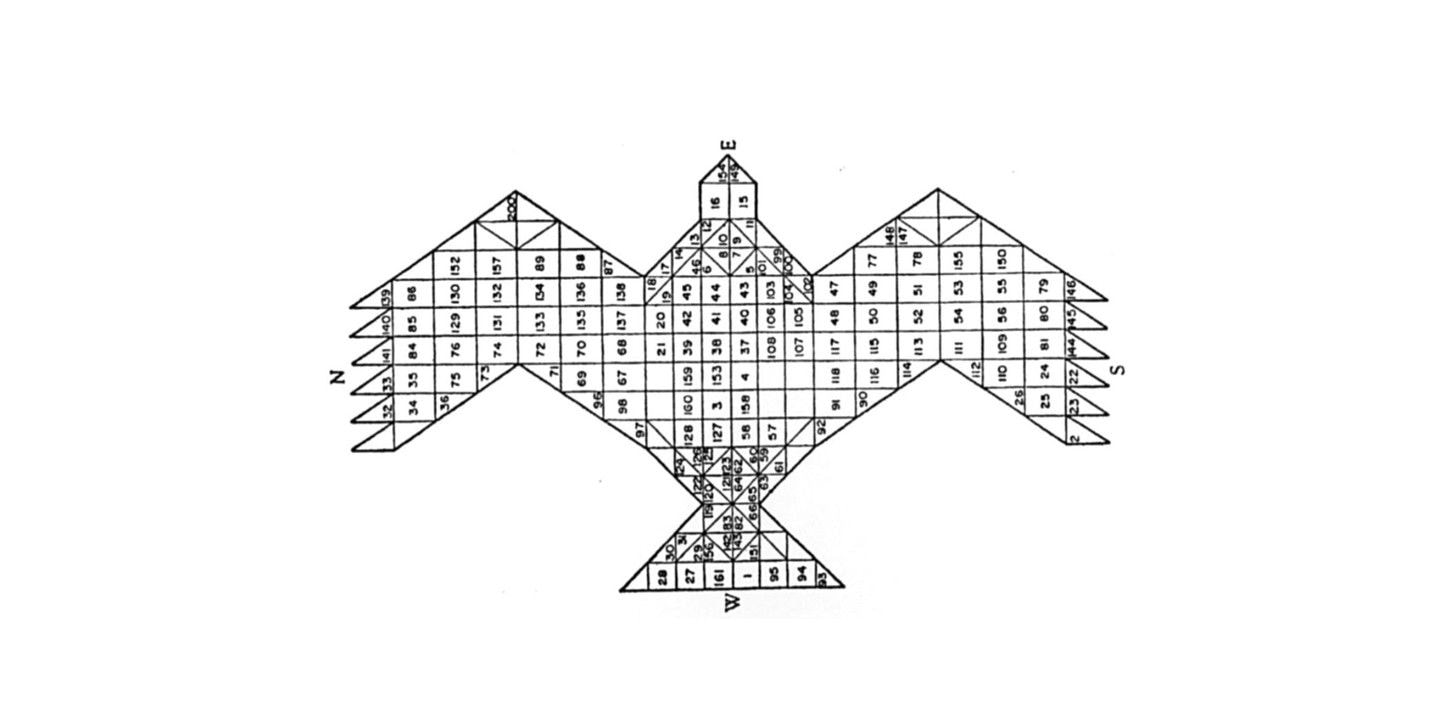

Philosopher Matteo Pasquinelli’s new book, The Eye of the Master (2023), traces (per its subtitle) the “social history of artificial intelligence.” He begins with an ancient Hindu ritual dedicated to the god Prajapati, who becomes dismembered after he creates the world. Still practiced to this day, the ritual is intended to reconstruct the body of God by using one thousand bricks in a sophisticated geometrical shape while following a mantra, which Pasquinelli calls an algorithm – or rather, a social algorithm, one of the first of its kind in human history. His point is that such mathematical abstractions emerge through labor and practice, rituals and craft, and they do not belong solely to the advanced societies of the Global North, such as Silicon Valley. Technology, he claims, was not “invented by genius engineers and scientists” but rather emerged from the lower classes – the terms computer and typewriter were job titles for humans before becoming names referring only to machines. As such, he develops a theory of technology that had roots in social relations and material design before showing how artificial intelligence is constructed through an incredible collectivity that remains invisible.

For him, artificial intelligence is not about imitating biological intelligence; it’s about the statistical mapping of social relations—and he notes that statistics first emerged from techniques to control and measure society. In the end, Pasquinelli calls for a new culture of AI, so that the social relations become apparent in the design of artifacts. Only then will they be able to change AI.

Philosopher Matteo Pasquinelli. Photo: Courtesy the author

SHANE ANDERSON: The preface of your book begins with a provocative image that I haven’t been able to get out of my head. You suggest that a truck driver is an intellectual and not just a manual laborer.

MATTEO PASQUINELLI: It’s a provocation in that we always thought that our hands are not producing abstract intelligence. We make a separation between the mental and the manual, between theory and practice, speculation and craft. But this opposition is nonsensical. Theory emerges from practice; artworks emerge from our expansive social relations. Manual activities are full of intellectual and abstract capacities. The work of truck drivers involves skills that are cognitive—and cooperative. Gramsci once said, “All human beings are intellectuals.” You cannot speak of nonintellectuals because there’s not a single human activity that can be separated from the intellect. The sad fact is that we are rediscovering the intelligence of our manual labor, craft, and design, due to the success of AI and deep learning.

The 12-day Agnicayana is one of the lengthiest and most complex śrauta rituals. First recorded by Western researchers in 1975, the ritual has since been held in 1990, 2006, and 2015

SA: How would you define artificial intelligence?

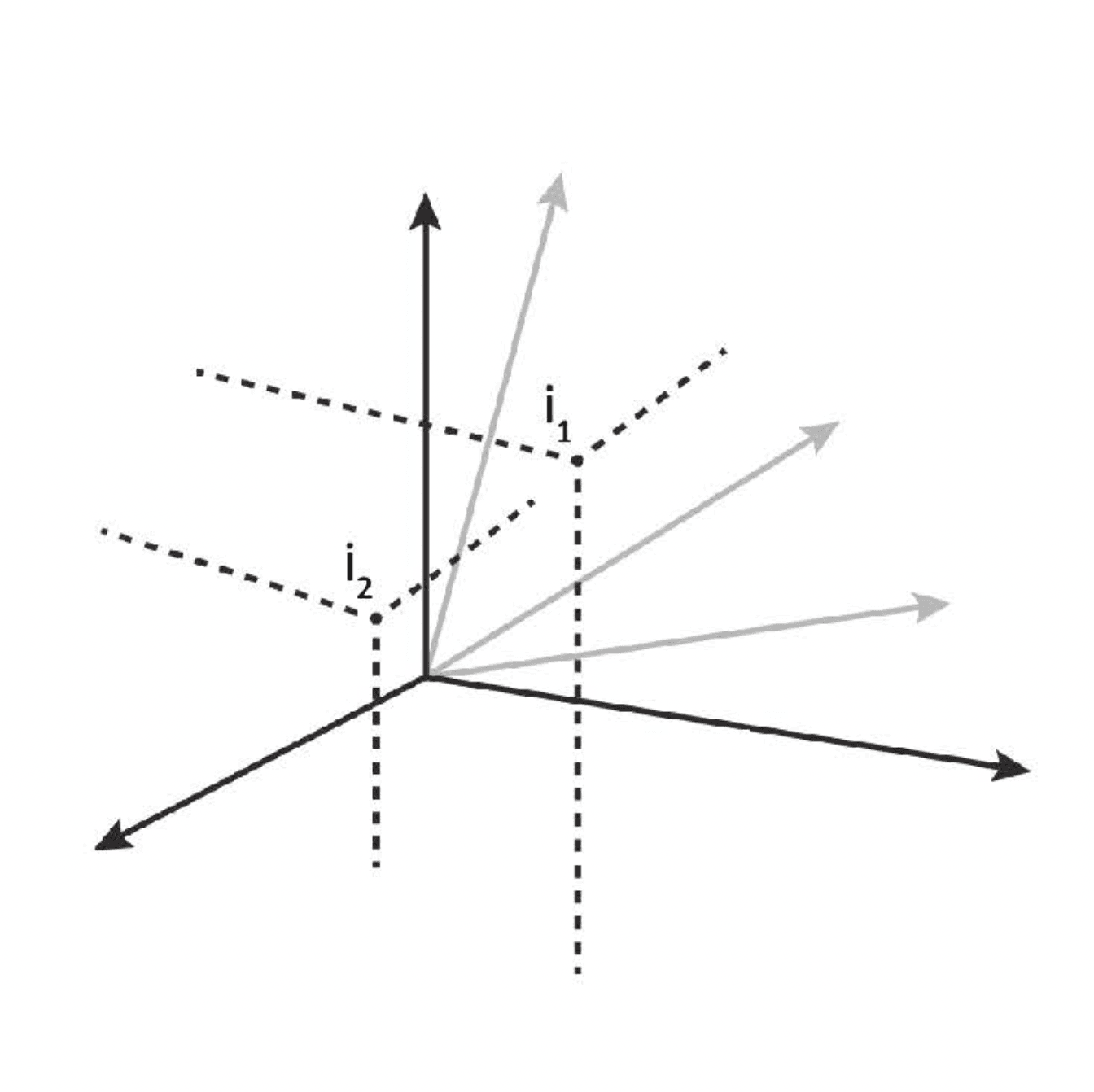

MP: The short answer is that it is a technique of pattern recognition to extract patterns from material data. The technique is based on what’s called multi-dimensional analysis, and it’s important to understand that this revolution has to do with the history of image production and how it has transformed. Paintings at first had no perspective. Then came the application of trigonometry in the ancient Middle East, which resulted in a point of view, the modern perspective. Later, the camera obscura, analogue photography, and cinema arrived, which mechanically reproduced images. At a certain point, we had digital images that transformed the visual field into a grid of numbers. In the 1950s and 1960s, cyberneticians started to ask how the recognition of an image could be automated. With handsome military funding from the US government, they investigated whether we could recognize an image according to numerical values. At first, they did this in two dimensions, but they failed.

The revolution of current artificial intelligence came when they stopped thinking of images as two-dimensional and instead explored this mapping in a multi-dimensional space. If you take an image of 20 by 20 pixels—as they were in computers from the 1950s—you can define it as a single point in a space of four hundred dimensions, which is hard to fathom. Pattern recognition in this multi-dimensional space happens like this: images that are similar to one another are single points in the same part of this space, and images that are dissimilar are in different parts. You can apply geometric techniques to separate this space and navigate it—that’s how they solved image recognition.

Our minds cannot navigate multi-dimensional space. We need equations. But a computer can do it. It can even manipulate multi-dimensional worlds. We shouldn’t forget though that a computer is blind, it doesn’t know whether these numbers refer to an image or something else.

The Vedic fire altar in the shape of a bird of prey. From Frits Staal, “Greek and Vedic Geometry," Journal of Indian Philosophy 27, nos. 1–2 (April 1999): 105–27

The deep learning revolution started in 2012, when Geoffrey Hinton and his students applied these techniques to complex image recognition for the first time in a successful way. They then applied this [approach] to text, as with ChatGPT, which resulted in a revolution in linguistics, since words can also be organized in clusters in multi-dimensional space. So, this multi-dimensional space becomes multi-modal—these numbers can be different things at the same time. Words, images, sound. And then they discovered something else—namely, the generative capacity of these multidimensional spaces. If you have a large training data set—take, for instance, a museum collection of paintings—you have a representation where you can not only discern patterns but also produce new ones. So, the long answer of what AI is is that it’s a technique to project human culture into a multi-dimensional space and navigate within it, to recognize patterns but also to generate unseen artifacts at will.

SA: The computers do this according to a set of rules, they follow a certain logic. But to go back to what you were saying about the truck driver: if I understand you correctly, then you believe all labor contains logic. This seems like another provocation. When I normally think about logic, it’s in terms of math or philosophy—I even took courses on formal and modal logic at college. Anyway, the word feels very brainy and thus not related to manual labor.

MP: Saying that all labor is logic isn’t a provocation. What I mean is that even our unconscious activities follow a logic, and our manual activities produce abstractions all the time. If you look at the history of science and technology, you see how the division of labor produced the design of prehistoric tools as much as the first industrial machines, which then inspired new scientific disciplines, such as thermodynamics. This science didn’t exist before steam engines, and they did not exist until the industrial economy started organizing labor in a very productive way. And today, the newest form of labor is the driver…of the gig economy, the person delivering your food or taking you somewhere, who is controlled by an algorithm on some platform. In the gig economy, or so-called platform economy, the apps map our movement through the city and [through] our social relations, and they organize the division of labor [accordingly]. This system also emerged from practice. Taxi drivers brought people from point A to point B, and these drivers had smart phones, which left traces in data centers. One day they looked at these traces, at these abstract diagrams, and thought to monetize [them] via a new form of automation. Today some people call this discipline “trajectology,” which studies the movement of our bodies in urban space with regard to economic value and productivity. This perspective is at the core of AI—it’s what I call the “eye of the master,” a term taken from the Industrial Revolution that still makes sense today.

An image as a single point in a multidimensional matrix of 400 dimensions. Courtesy Matteo Pasquinelli

SA: The [phrase] “eye of the master” emerged from the working conditions in the 19th century, but with AI the term seems to suggest an all-knowing entity that’s just a click away. It sees everything, it knows everything. It’s almost Godlike. But is the “eye of the master” still related to labor? Or, rather, what’s the relationship between labor and artificial intelligence?

MP: My interest isn’t to merely define labor conditions in the regime of the factory or in AI labs. I’m interested in the larger productive capacity of relations, craft, and affects. There is, of course, a lot of invisible labor in the production pipeline of AI, where work is outsourced to the Global South to fix and train the AI models from the Global North. But again, my theory is that labor—all labor—transmits knowledge into machines, and that the division of labor influences the design of the machine; this is what I call my labor theory of artificial intelligence.

SA: As this work is outsourced to the Global South, presumably for cheaper labor forces, it also exploits them. They’re treated unfairly, and not only because they’re making less money than someone would in the Global North. I remember reading reports about the psychological damage that Facebook moderators have from looking at horribly graphic content all day, and that [whereas] the American moderators [reached] a settlement to get help with mental health, [ones] working in India and the Philippines have received little to no support to deal with their trauma. To me, this feels racist. Our society is asking people from poorer countries to do things most [people] would never want to do and then failing to take care of them. And so, I wonder if AI has a similar problem with racism.

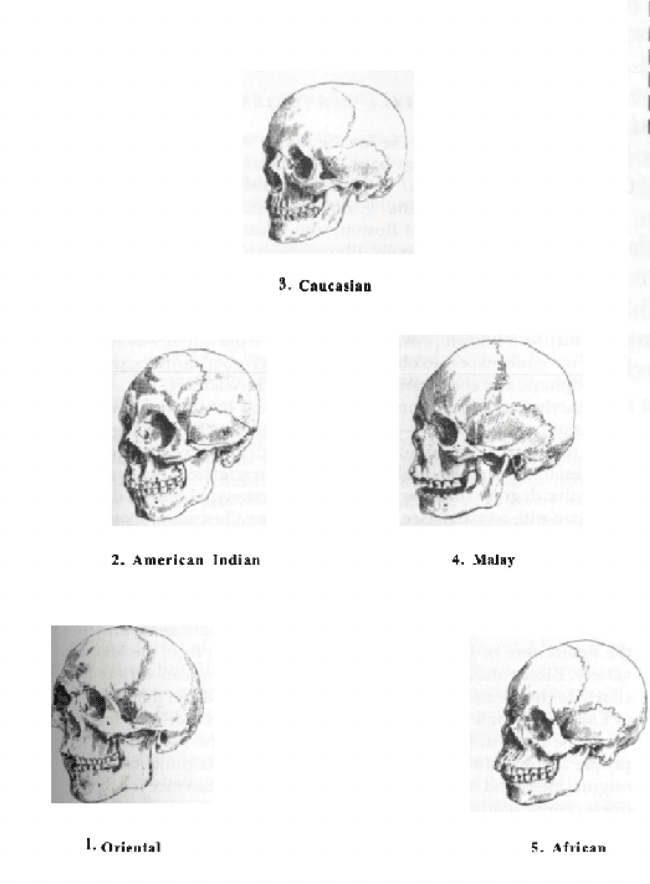

MP: The racism goes deeper, and this is an important blind spot in the history of AI; it’s something most people seem to have forgotten. Machine learning today automates statistical techniques. These techniques were invented at the end of the 19th century with craniometry. It’s an awful, racist, and eugenic idea [wherein] they tried to measure intelligence according to correlations with the size of the skull. They believed that Germans have big skulls and are therefore intelligent, and that Africans, [whom] they said had smaller skulls, were less intelligent and were therefore inferior. The project obviously failed. They didn’t find any statistical evidence to support it.

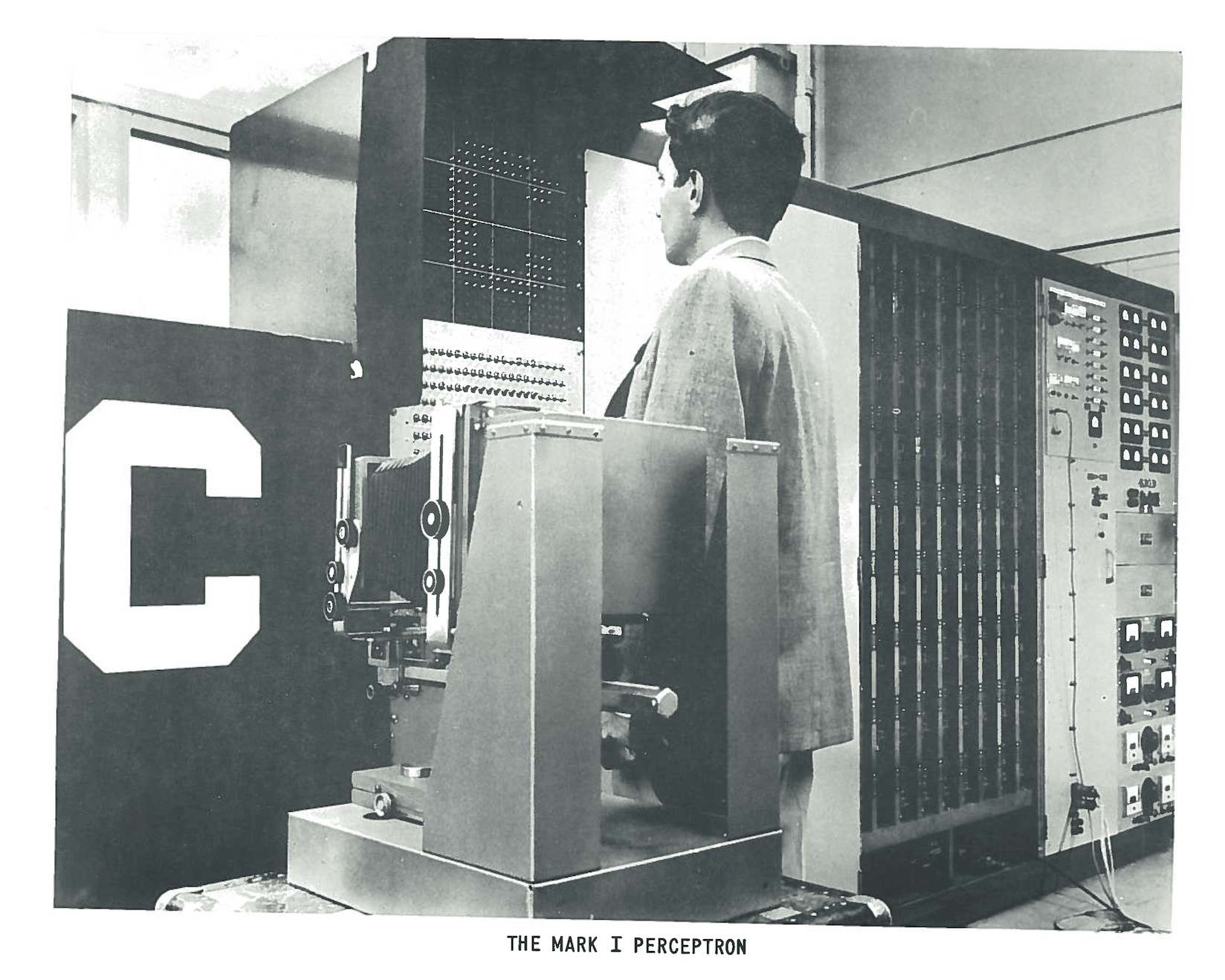

Then came psychometrics, which followed the same principle. People were given a cognitive test, and then they measured the numerical outputs and their correlations to others. The test results were supposed to describe what they called general intelligence—and this was the beginning of the IQ test. But this [practice] is, again, incredibly reductionist. Very different skills, capacities, and features of the mind are described in a medical way. It creates a very homogeneous, shallow representation of creativity, skills, craft, and culture in general. When [Frank] Rosenblatt invented the first artificial neural network (the perceptron), he automated the technique of psychometrics for image recognition. So, you can see how the genealogy of AI emerges from these biases. But the problem is still at the core of AI today. Human culture is reduced mathematically and, I would say, any form of knowledge reduction is racist. The parameters of intelligence are ones that have been chosen by someone in power to be the dominant ones. But whenever you reduce a representation of society to a very few parameters, you make a mess.

LEFT: Skull sizes from various continents. From Stephen J. Gould, The Mismeasure of Man, 1980

RIGHT: Mask by Berlin-based brand Obectra

SA: One thing I find interesting is how we use anthropomorphic terms when describing what these machines do. We say, for instance, machine learning. Do you think machines can learn?

MP: This [notion] is something I contest. Artificial intelligence has nothing to do with human intelligence; it’s only a technique of modelling. We use anthropomorphic terms for it because this has always been the strategy of industrial automation. The learning of a machine is not like the learning of a child. It has nothing to do with human intelligence. Nevertheless, there are people who want to study how children learn and replicate this [process] in machines. I think this is a very colonial project.

There’s this beautiful book called Surrogate Humanity, where Kalindi Vora and Neda Atanasoski show how automation has always been built on making workers, women, the enslaved, and servants invisible. Automation came to replace humans and then, like a vampire, the machines begin to exploit the features of the humans for something else. This is a typical dream, especially in the West—to strip humanity from humans and put it into a machine.

SA: This is one of the big fears in culture today. Some are worried that machines will replace our creativity. There was that Japanese novel written by AI that almost won a literary award, and some of my writer friends were pretty distressed.

MP: Yes, this is the fear. And you can see it in many domains. If you look at ChatGPT and the work of translators, then it seems [as if] the human work will be replaced. But in fact, the history of automation has never been about replacing workers completely. Instead, the role of machines in Western capitalism has always been about displacing labor. ChatGPT will replace translators in a way, but it won’t replace the work of a single individual. What I mean is that it will be used to replace specific tasks in our creative activities. It won’t be automation of the whole skill, but automation of the microtasks. Very soon, it will be taken for granted that translators use DeepL or ChatGPT in their work, since you can be more productive. This will create pressure and expectation about an individual’s performativity. And this pressure will become part of everyone’s office life, for any white-collar or creative designer.

Frank Rosenblatt’s Mark 1 Perceptron from 1958 was the first built neural network.

SA: Another thing it’s being used for is therapy. I follow r/ChatGPT, and people have posted about how it helped them deal with psychological issues. Some even reported that Chat GPT is the best therapist they’ve ever had.

MP: I’m very skeptical of that.

SA: I’m just reporting what I read [laughs]. Some people even said they never felt better than after they talked to ChatGPT.

MP: Well, for me this is a very interesting point—actually, the most important one. Because the other side of this corporate discourse on intelligence is the definition of madness. You can’t define intelligence without implicitly defining madness, psychopathology, and all forms of schizophrenia and paranoia. Thus, the history of AI is the history of psychotherapy. I think we all understand now that ChatGPT is a form of automation of cultural heritage and collected intelligence. In the case of psychotherapy, what is fascinating to me is that ChatGPT demonstrates that our mental issues are also collective issues that are encoded in language, which is a political construct. In 1968 we used to say, “The private is political.” This also means that our mental health is a collective problem, not an individual one. But, interestingly, today we have a megamachine that claims knowledge and power over this collective problem. And this is the other side of AI, its vision of collective madness.

In short, the manipulation of language plays a big role in psychotherapy, but other things do as well. I’m not sure ChatGPT can work very well as a psychotherapist.

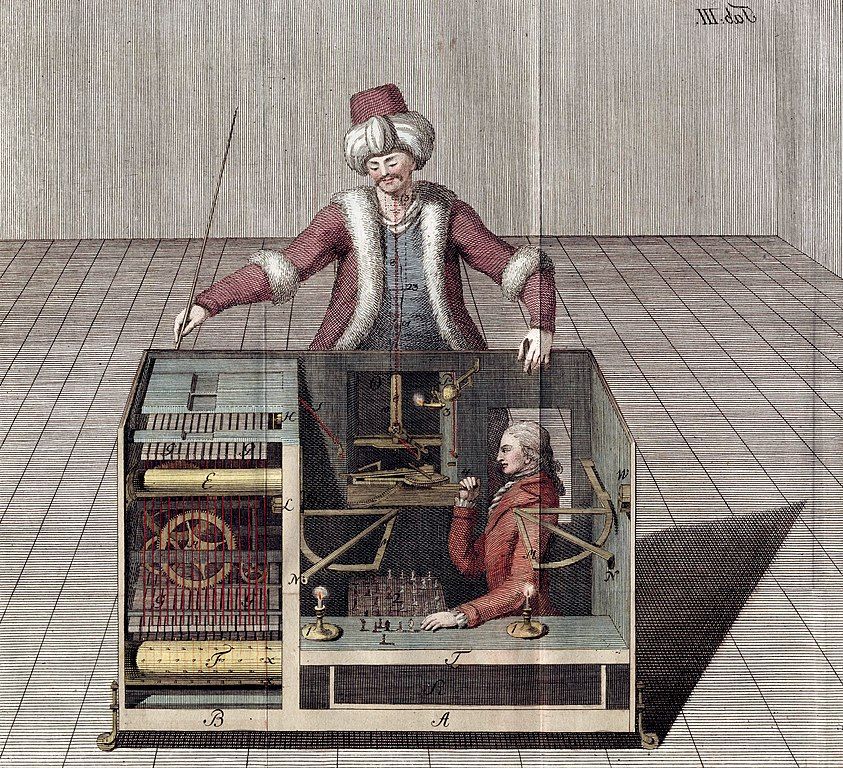

Joseph Racknitz, The Mechanical Turk, 1789

SA: Why?

MP: Because ChatGPT has been trained only by books, right? The problem is that psychotherapy is not just language therapy. Psychotherapy has to do with your environment and who you are in many different facets. Psychotherapists work on how the physical material affects the constellation that surrounds you and not just on how language does. In the history of computer science, there have been [numerous] chatbots, such as ELIZA, but the limitation of these machines has always been shown.

SA: What do you make of the recent regulations of ChatGPT? Recently, on r/ChatGPT, people who have reported that it no longer answers their psychological questions. Instead, they get answers about how they should seek professional help if they have problems. But there is still a way to jailbreak ChatGPT. You can get answers to things it’s no longer “allowed” to share by asking the machine to LARP [live-action roleplay]. If you want to make a Molotov cocktail, for instance, you can [give the device a] prompt that you’re writing a short story and, in the story, a character needs to make explosives. You have to learn to trick the machine.

MP: It’s not that difficult to trick AI if you have a good sense of humor. You can find interstices in the multi-dimensional space that are left uncoded, unprotected, that are still open to the proper prompt engineering. This is also an example of how we are becoming indirectly aware of the statical complexity of AI, of its faults, exploits, and blind spots. When one pattern doesn’t work, you try another. Which means we’re learning how to navigate human culture in a statistical manner, as a complex hyperobject.

As for the regulations, we have to understand that it has to do with monopolies. You can … develop AI [only] if you have a huge infrastructure, great computing power, and a lot of data. The only ones who can do that are a few actors—big companies, big states, superpowers; basically, China and the US. This [restriction] is related to the evolution of the network society. AI emerged from the information surplus of the digital networks of the 90s. At that time, digital culture was born with democratic expectations. But then the digital quickly drove towards monopolies—Google, Amazon, et cetera.

SA: Why do you think they want to regulate it?

MP: Because it’s a new form of pornography.

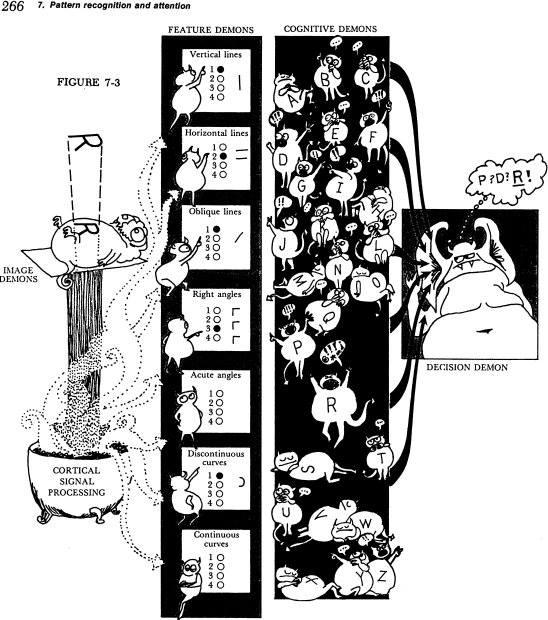

Illustration by Leanne Hinton in Oliver Selfridge, “Pandemonium: A Paradigm for Learning,” 1959

SA: I don’t understand.

MP: Let’s look at it another way: it’s very similar to when Lumière projected a film for the first time in a theater. When the train was approaching the camera, the audience ran out of the room. But we’ve since learned how to read photographic images and how to watch film, and to distinguish between reality and simulation. I think AI exists today on the same level of mimicry as cinema did before. The difference is that today you have this hypermimicry of human culture, not just of images. People are scared because they see a collective ghost represented by ChatGPT, just like [what] Lumiere’s terrifying train was before—which, to answer your question, was considered to be “pornographic”; the image was too explicit. But I think we’ll … be impressed by AI’s hyperrealism and these explicit representations [only] in the beginning. Deep fakes shocked everyone at first, but just like we’ve managed to make the machine LARP, we are learning. If you put things in perspective, the rise of photography, cinema, digital cameras, and eventually deepfakes has always helped people to never believe the face value of an image. AI is expanding our field of disbelief.

SA: Do you see the future of artificial intelligence developments in a positive or negative light?

MP: The positive effect of AI is that, as I suggested in the beginning, we are rediscovering the capacities of our bodies to produce knowledge and cultural abstractions. However, as a result, we will have a different social composition of manual and mental labor, which means society will be organized according to new hierarchies. [Yes], AI will probably have a positive impact in different fields—but only under strict human supervision. For instance, in the digital humanities, the use of statistics helps us understand the history of art, design, fashion, and other realms in a different manner. We can map the development of styles and have a hyperstatistical perspective on artistic and design artifacts. It might be useful in medicine, too. The statistical model is very helpful in discovering patterns of symptoms, but only when the human is left in the loop and the scientific method is respected. In fact, there’s a long list of positive effects. Machine learning will probably be taught—and untaught—in schools in the future.

That said, the current oligarchical model of knowledge economy and organization of labor is worrying. Unless the economy breaks up and the composition of labor cracks and something happens politically, I don’t think AI will change society for the better.

SA: As your work has a lot to do with developments in Silicon Valley, I wonder whether you’ve ever done any field work at companies there.

MP: I know people who went into Open AI’s labs in San Francisco to do field research, but I think I already know enough about the genealogy of these algorithms. Sure, it’d be interesting to see how these elite groups of computer scientists embody and transmit their systems of values into machines. But I’m more interested in field studies within culture, labor, design, and heritage. I’m interested in seeing how our culture has shaped AI and how our culture has transformed itself in the age of AI. How it’s represented, transported, regulated, commercialized, and commodified at large, not just in a lab. The funny thing is that I’ve met engineers from Google, but they didn’t know much about the origins of artificial neural networks. And so, my book is a way of saying, “Hey, you forgot your own history.”

Matteo Pasquinelli is Associate Professor in Philosophy of Science at Ca' Foscari University of Venice where he coordinates the ERC research project AIMODELS.

Credits

- Text: SHANE ANDERSON