CYPRIEN GAILLARD: L’Origami du Monde

|DIETER ROELSTRAETE

CYPRIEN GAILLARD has a thing for monuments—their grandeur, obviously, which is sometimes matched by the majesty of his own art projects (his 2012 film Artefact, originally shot using an iPhone and subsequently transferred to 35 millimeter film, comes to mind) but also, much more pointedly, the inevitability of their ruination—and the greater the monument, the more compelling the drama of its demise. Although Gaillard is certainly sensitive to the luscious, entropic poetry of material decay—a sculptural sensibility suffuses many of his image-installations—these monuments do not necessarily have to be made of blood, sweat, steel and stone. Indeed, the “monument” at the heart of the artist’s latest large-scale project is a prime example of just such an immaterial edifice—a paper empire if ever there was one: National Geographic Magazine, the world-renowned official publication, for exactly 125 years now, of the Washington, DC-based National Geographic Society.

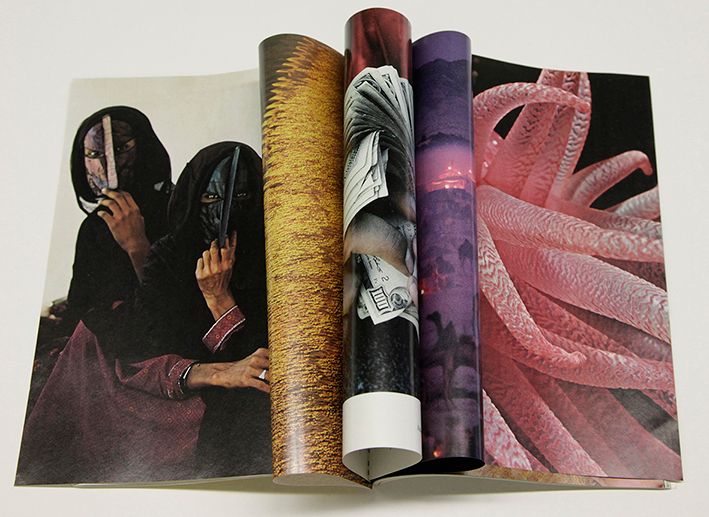

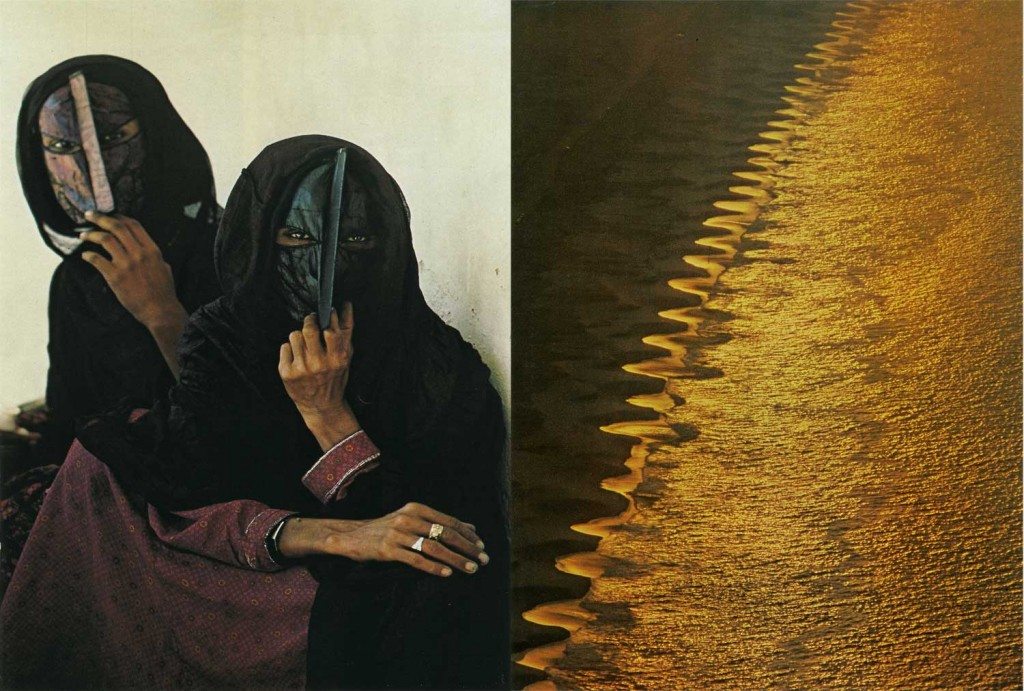

Back in an immense temporary workspace in the industrial far west of Berlin’s Moabit district, I am allowed a peek in to see this project of folds take shape: hundreds of pages full of characteristically colorful photographs, carefully cut from a lifetime of National Geographic issues, lie strewn and scattered across a dozen makeshift table tops, waiting to be assembled in a well-ordered phalanx of small paper sculptures. They are sculptures (tiny monuments, if you will), not collages: no glue is used in putting them together, just a single cut, a single fold, a single bending gesture—there are rustling echoes here of the age-old sculptural language of balance and tension. (Roland Barthes in The Rustle of Language: “the rustle is the noise of what is working well.”) Once completed—a painstaking process of selecting and juxtaposing just the right images from the deluge of National Geographic photography—the objects will resemble crystalline relics, delicately propped up inside glass vitrines. With a little more imagination, the contours of a floral formation start to emerge; there are faint traces (inevitably, in this landscape of folds and creases, tents and erections) of genital imagery—think of it as L’Origami du monde. It is a fractured, kaleidoscopic world, governed by the serendipitous, associative logic of two, three, four, or five images talking to each other across the divide of continents, cultures, and generations—sometimes in the universal language of formal resemblance (the roof of a collapsed house looks like the foamy crest of a giant wave), sometimes in the lingua franca of some deeper conceptual convergence (a girl wielding a baseball next to a Masai warrior with his spear), sometimes plainly speaking in tongues, or just in jest (the curve of the Guggenheim in New York opposite the snaking trail of a bushfire). Indeed, the work could have been titled either Geographical Analogies or Floods of the Old and New World—note the fluvial, diluvium ring of the latter—had these titles not been given to two of Gaillard’s earlier projects, formally and materially quite comparable to this one: a flood of analogue imagery; a picture of the world on the cusp of old and new.

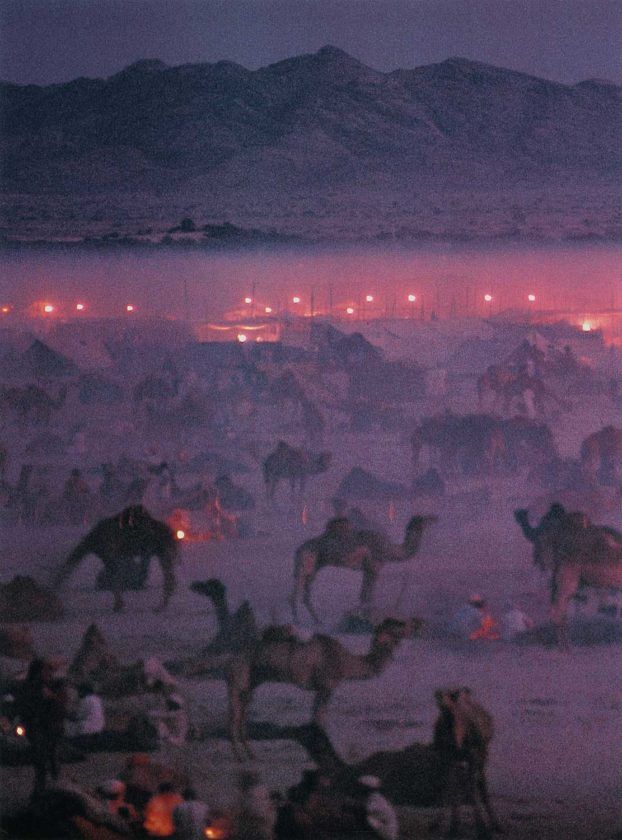

Most of the photographs that make it into these bouquets, I find out, are taken from National Geographic issues from the 1960s, 70s and 80s—the era we can probably look back upon as the magazine’s golden age. This choice is partly informed by the artist’s wariness of facile nostalgia—this is no homage to long-lost ways of seeing, rather more like an irreverent, at times even iconoclastic, joyride through an imagescape defined by still-familiar markers: the world unfolding in these foldings is still recognizably ours. At the same time, however, through the iconic yellow frame of a cover design that hasn’t changed for over a century, we catch a glimpse of a steadily receding past—who needs National Geographic in the age of high-speed, hand-held image searching, memes, tumblrs, and various other types of “viral” visuals? The coming of the Internet arguably ushered in the end of this particular chapter in the history of publishing culture, and this is precisely the moment—sometime in the nineties, when Gaillard was still a teenager—when National Geographic as a brand “lost it”: first it sold its soul to television (when does one ever see anything national, or anything remotely geographic, on the National Geographic Channel? How many reality-TV shows about hoarding and storage wars can one actually watch?), then followed a series of subtle and not-so-subtle shifts within the magazine’s visual content and imaging policies (as the artist put it: “how many more features on life among the sharks do we need? Aren’t people more interesting to look at?”). Of course, these focal shifts are inextricably bound up with deeper changes in culture: looking at some of the photographs (especially of people—of “others”) published in National Geographic issues from the 1970s, it is hard to imagine getting away with doing the same today, on the other side of the historical divide marked by the rise of political correctness, by the emergence of postcolonial theory and assorted critiques of empire. Here, the implicit critique of the imperial optic (“did they really print that?”), really an Institutional Critique of sorts, folds back into Gaillard’s long-standing fascination with civilization’s melancholy afterlife—with the sorry yet spectacular sight of mighty monuments, now lying in ruins, overgrown with the weeds of time.

Catastrophe is a recurring theme in Gaillard’s work, which occasionally indulges in what could in fact be called “catastrophilia.” (“Is that all there is?” is what it asks of us, in Peggy Lee’s mildly amused plaintive tone.) Fittingly, for a crucial stretch of ten, fifteen years in the 1970s and 80s, National Geographic became a dependable purveyor of such exact images of catastrophe, painting a rather bleak picture of life on Planet Earth in the process—“graphic” rather than “geographic.” Extensive reporting on oil spills, nuclear crises, and acid rain; newsflashes from the “planet of slums” and the global archipelago of waste; spectacular accounts of natural disasters and the terrible ecological legacy of human hubris… all quintessentially Gaillardian themes. National Geographic may well have played a crucial role in the slow but steady emerging of today’s environmental awareness (as well as that of a broadly humanitarian consciousness—recall the celebrated cover portrait, shot by Steve McCurry in 1985, of Sharbat Gula, the enigmatic blue-eyed Afghan girl). On a related note, it is tempting to project the culture of 1970s political paranoia back onto the vogue for aerial photography in those years—for oversight, surveying, and surveillance. Part of the military-industrial complex’s “scientific” superstructure or just outside of it looking in, National Geographic’s all-seeing eye appears at times not so very different, and geographically not so far removed, from that of the FBI or CIA—or, why not, the NSA. (Just Googled it, and in fact: the National Geographic Society’s headquarters in Washington, DC, are a mere 23 miles away from the NSA office in Fort Meade, Maryland—I’m pretty sure the latter’s Kaaba-like black monolith must have featured inside the pages of National Geographic at some point or another.) Gaillard’s relationship to this dream of total oversight, the Olympic viewpoint of the international geographer, is an ambiguous one to say the least—the lure of totalizing thought certainly animates some of the thinking behind the project. Yet it is telling that the one art-historical reference that comes up in our conversation during my visit to his temporary studio is to the work of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, the 18th-century Italian master of labyrinthine architectural capriccios. It is no coincidence that Piranesi is known today for his elaborate treatment of two motifs in particular: the prison and the ruin—the Janus face of so many dreams of totalization.

Credits

- Text: DIETER ROELSTRAETE