Coup de Net: METAHAVEN’s “Black Transparency”

|Thom Bettridge

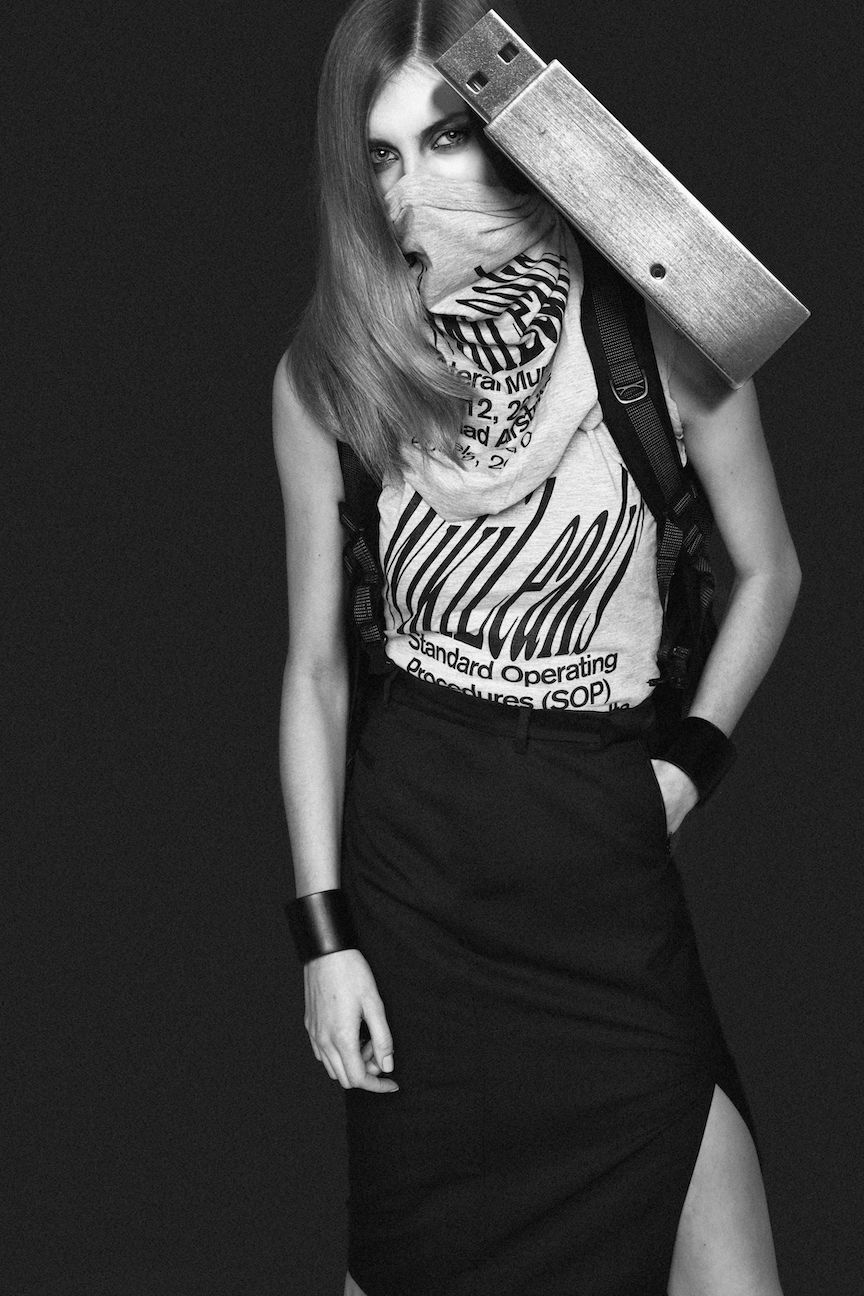

METAHAVEN’s newly released book Black Transparency: The Right to Know in the Age of Mass Surveillance (Sternberg Press, 2015) is a winding manual on the geopolitics of government secrecy and its combatants. Part essay, part zine, the Amsterdam-based design studio’s book focuses on the “how” as opposed to the “what” of transparency, zeroing in on the paradox that the fight for accessible knowledge (by groups such as WikiLeaks) is often carried out through necessarily opaque and propagandistic means. Black Transparency swallows its own tail in pursuit of its subject, following the un-coiling and re-coiling of ideology and information at the hands of whistleblowers and organizations. In a Chutes and Ladders-style infographic insert, the authors trace transparency back to its roots in Tacitus and the Magna Carta, and chart how “the right to know” has splintered and developed across recent decades. Packed with a mountain of sources—ranging from an interview with the anonymous designer of the WikiLeaks logo, to an master’s thesis written by Muammar Gaddafi’s son, to the protean status of Crimea on GoogleMaps—Black Transparency is a non-fiction document that reads like a spy thriller. As Metahaven writes, “Indeed, the facts emerging under black transparency are so many and so rich that science fiction authors ought to fear a coming unemployment; whistleblowers are the ghost writers of the future.”

Metahaven has now designed the visual identity for the group exhibition “Transparencies,” which is ongoing at the Bielefelder Kunstverein and opens November 20 at the Kunstverein Nürnberg. Following up on their profile in Issue #26, 032c’s Thom Bettridge spoke with Vinca Kruk and Daniel van der Velden of Metahaven:

THOM BETTRIDGE: Transparency is such a tricky concept. In categorical terms, something transparent strives to be an invisible barrier. Transparency is therefore un-seeable until it fails, so the only way to discuss transparency is through moments of its failure. Your concept of “black transparency” seems to allude to this paradox.

METAHAVEN: Black transparency relies on the notion that if you’re trying to create transparency in the world by revealing secrets—or by blowing whistles—then this transparency is interwoven with your own opacity. WikiLeaks has taken on a crucial role in this re-definition of transparency. It’s only when there are stains on the glass that you start to notice that there was transparency in the first place. In design terms, transparency is invisibility. The classic notion of invisible design—or design that’s so effective that you don’t even notice it—is necessarily impossible. The book tries to explore this too, especially when transparency gets endowed with big ethical and political motives, revealing secrets in defense of the public.

From a design and production perspective, the book itself has a very particular quality to it. The size, the paper stock, the typeface all feel more like an airport novel—like a Tom Clancy book—than a classic artist’s book.

We had it produced at a Danish printer that does high-volume thriller novels. And we started to work with this printer to arrive at the feeling you just described.

It also plays into a certain seductive aura surrounding these issues of transparency and WikiLeaks, which are represented in the news in a very thriller novel type of way. And similarly we’re seeing a return of Cold War concerns and attitudes—both in the news media and in Hollywood—where Russia is once again becoming this exoticized, villain-like Other.

It’s definitely become that. The book describes how, at its beginning, WikiLeaks was seen as another pro-democracy NGO, with some added Wikipedia flavor. It was explicitly about exposing non-Western authoritarian regimes, though already in 2009 it had released Guantánamo Bay’s Camp Delta operations manual. The Cold War spectral overtones that are dominating now started to appear around 2010, when WikiLeaks and its adversaries shifted from asymmetrical to symmetrical confrontation, and have only gotten stronger after Russia became involved. Those events do suggest a Cold War-type geopolitical narrative that’s appearing again, but appearances can be deceiving.

And it’s interesting to see how these 20th century tropes mutate as they re-appear. For example, Foucault’s idea of a surveillance society—that he explains using Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon—seems unequipped to describe surveillance in a digital age. We’re not sitting in a prison being watched the invisible eye of the state. We’re now constantly in a process of broadcasting our lives and voyeuristically observing each other.

When somebody becomes a whistleblower, they can reveal information of companies or states, but at the same time these companies or states are already enacting surveillance on their subjects. So it’s a double-bind. Bentham’s panopticon is insufficient to describe this current state, in the same way that a glass building façade is insufficient to describe transparency. It’s become much more complex. There’s surveillance, but there’s also self-censorship—as in the way that speech is influenced by its perceived chances to be Facebook-liked or retweetable. There’s all kinds of speech acts and modes of vision at work at the same time. As part of the book, we traced transparency’s trajectory through language, from a description of a material state to a metaphor for clarity, and eventually, organization. There’s this dream of a world without secrets, and a history of governmental structures that sought to realize it—for example, the League of Nations. Quite separately from that, yet running in parallel in the transparency narrative, there’s the idea that the release of information can act as a trigger for systemic change. In the 1990s, researchers at IBM studied the effects of grains of sand being added to a pile, one by one, causing its eventual collapse. In the mid-2000s there were many theories about information cascades bringing about similar forms of change. Organizations like WikiLeaks were built around these ideas. The tricky bit is that one never can know exactly where the change will lead to, and if and how it will backfire.

So do these breaches necessarily happen from a condition of over-saturation?

The beginnings of the Arab Spring in Tunisia are a classic an example of an information cascade. But many more factors than information alone were at work in triggering the revolution. With the emergence of large-scale leaks, where entire databases are made public, the information itself is no longer the central fact. It has to be unearthed from thousands of pages. But in the longer run, the WikiLeaks cables have an archival or historical role that even outweighs their role in the present. The archive serves as a backdrop to connect emerging narratives.

What types of narratives?

Many emerging narratives on the geopolitical stage are, in the context of mainstream media, simply presented as “news.” Events seem to lack history, and appear out of nowhere. For example, the Western mainstream media who applauded the US- and UK-led invasion of Iraq in 2003—to be clear, that is almost all Western mainstream media—have not been keen on exposing the direct connection between that invasion and the rise of Islamic State. Instead, Islamic State is referred to as a “cancer,” a bunch of “monsters,” or “barbarians,” which they may very well be. But such words leave the West’s own role in creating this threat comfortably out of the picture frame. The archive, then, provides concrete evidence for those who want to make a different case. Databases like Cablegate, the Syria files, and the Stratfor archives offer unprecedented context to counterbalance “news.”

It seems as through most new subversive enterprises contain some type of brand machinery. For example, these color-based activist movements like the Orange Revolution in Ukraine have the same brand logic as Lance Armstrong’s Livestrong bracelets. Black Transparency begins with a chapter on the WikiLeaks logo. Why were you fixated on the logo as a starting point?

In the post-political context of the 1990s and early 2000s, arguably, revolution lost the aesthetic components that it still possessed during the Cold War. The dissolution of the Left, and the de-politization of human rights movements, has created not just a political but also an aesthetic vacuum, in which the “color revolutions” appear, a Pantone swatchbook of pastel hues where the most overtly revolutionary color of the 20th century, red, is categorically avoided. We see the irony, 032c! The Dalai Lamafication of the revolutionary aesthetic has brought about its identification with earthy and flowery tints, fabrics, and plants. While each individual uprising is based in a local context, there undoubtedly is a pattern to the color revolutions. Add to this the identification of revolution with information technology, first diagnosed by the West in its take on Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution, and culminating in Iran’s 2009 Green Revolution, with Twitter’s famous postponement of its server maintenance on request of the US State Department. For WikiLeaks, it was about the need to be perceived as a credible organization. The logo was the only image the organization published in the first two years of its existence. They didn’t have faces or any type of celebrity outside of their logo. Then the logo itself is so eerily different from what you normally see. It uses known tropes such as globes, but then the hourglass and the candle-like dripping, and stuff like that, are something that you might expect more of a CorelDraw homemade Salvador Dalí painting.

It looks very amateurish.

But in a good way. It’s so sticky. Many NGOs have these very clean identities that make them presentable in policy circles. That also stands for the way in which all their authoritarianism top-100s and corruption indices participate in the status quo in some fundamental way. WikiLeaks has always been and will always be something entirely different.

How would you describe the world vision behind a transparency group such as WikiLeaks? In the subtitle of your book there’s this phrase “The Right to Know,” which has the type of language one would associate with the American Revolution, or the type of liberal politics championed by the Enlightenment.

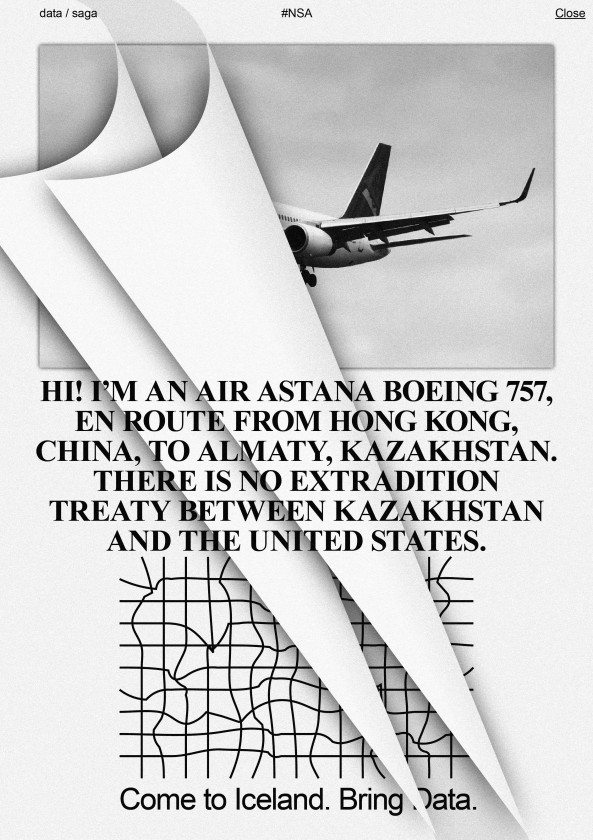

American liberal, and most of all, libertarian political circles have been the most vocal about transparency as a way to curb the power of the executive branch. But ultimately there are limits to that, because transparency—like surveillance—has gone global and can be framed in an American political or juridical context only to the extent that the US as a power exerts powerful effects across the world. Daniel Ellsberg’s leak of the Pentagon Papers was fully contained within a US political ethos, and though he was cleared from prosecution, Ellsberg was fully prepared to answer to the American legal system when he was held accountable for his heroic act. Chelsea Manning, who gave the Collateral Murder video and many other files to WikiLeaks, now serves a 35-year prison sentence in a US prison. She perceived a direct emotional relationship between herself and events in the world, making the personal geopolitical. Together with Holly Herndon, Jake Applebaum, and Mat Dryhurst, we were so very honored to interview Chelsea Manning for Paper magazine recently. WikiLeaks, as a matter of principle, has never identified itself with any jurisdiction or border. So when it publishes leaked information, the idea of a greater purpose shifts from the national context—the US—directly to universalism, in accordance with the infrastructure of planetary-scale computation that enables and facilitates the leaks themselves. Then, with events like the recent hack—and subsequent leak—of the Ashley Madison database, for which there is no other imperative than damaging people, it’s clear that there are in effect no norms for black transparency. Everything that can happen, will happen.

I’m curious about your opinion on the Ashley Madison leak. It’s also different in the sense that it revolved around sexuality and shame, rather than government secrets.

There’s a kind of libidinal component to transparency that’s in every leak, not just the Ashley Madison leak. Leaks don’t just serve a rationally justified need for information, but also cater to the very sensation of the exposure itself: the secret revealed.

In what sense are all leaks sexual?

It’s the fact that you’re having a very crude form of intimacy with information.

There’s all these weird mirroring effects. Transparency groups often operate against the notion that the government is watching us, but the method wherein to bring that down is to enact our own surveillance on the government.

The State vs. the People binary is a very non-nuanced binary. There are so many narratives running at the same time. The cloud increasingly tells us exactly what we want to hear—either by having us live in filter bubbles of our own preferences, or by conscious design. In the case of Crimea, for example, there were different versions of it on GoogleMaps. If you Googled it in different countries, it gave you different results as to whom the territory belongs. If you Googled it in Ukraine it was part of Ukraine, for Google in Russia, it was Russian. Which version is more real? All of those realities and modalities are simultaneously coexisting.

We’re also seeing a shift in consumer technology that’s geared towards privacy and encryption—special messaging platforms, email servers, routers, etc. Secrecy has taken on a certain market value.

Take for example Protonmail, the email provider that brands itself as an 100 percent secure data haven in Switzerland. In some way, it is borrowing from the country’s history of bank secrecy and status aparte in the geopolitical space. The consumer value of privacy depoliticizes the free thought, free speech, and free association and conversation rights that everyone deserves. But when you talk to someone about privacy, you can never be sure that you’re both talking about the same thing. Privacy is an ancient paradigm to many people. It’s merely the way that mainstream media frame the issue of surveillance to what they perceive as their consumers.

And there is such a longstanding connection between privacy and aspiration luxury. Take for example the way a tinted limousine window works as a luxury apparatus. It revolves around this idea of being able to see out, but having no one be able to see in.

The Blackberry, as the first smartphone, was famed for its secure messaging system. It was sort of a parallel to that tinted window. And then Blackberry of course has the word “black” in it, which connotes both luxury and opacity. And now you have Apple becoming more of a product that brands privacy and encryption as part of its design aesthetic. But at the same time, it’s a mainstream product for millions of people.

Privacy is then transformed into a standard bourgeois privilege.

Even the assertion “If you have nothinbg to hide, you have nothing to fear” is a class proposition. It plays on people’s self-perception, of the way in which their thoughts and actions matter or not. People who say that they have nothing to hide are being unnecessarily humble with regard to the wider importance of the things they have in their lives and the people to whom they relate. It can even be true that you have nothing to hide, but what if you gave me your PIN number, your email accounts, and your whole money-data map? Almost no one would do that.

Tell me about what’s next for Metahaven. I heard that you’ve been researching Russia.

Something we address in Black Transparency is the idea that a state, in order to appear modern, has to hide the fact that it has secrets—and the book is about the eternal re-discovery of this lie. This trope around the state falls flat with Russia, where there’s never been real transparency—which may be why black transparency’s protagonists rarely criticize Russia directly. The book describes how WikiLeaks once announced a major leak on Russia, and then held back and didn’t publish. Russia plays an “Other” to the west, the un-West in some sense. Its actions on the world stage and its symbolic role in the media serve this ex nihilo otherness–and this is what interests us because at its core—conceptually—this is a subversive act. It’s been seen as a recent postmodern turn, but the idea that truth is a creative work of fiction has much older traces in Russian culture and philosophy. And one doesn’t need to appreciate Vladimir Putin to appreciate that reality can be viewed through many different lenses. You could say that subversion here falls outside the liberal lens of what it is to protest. Our moving image project called The Sprawl is dealing with things like Internet propaganda, perception, and subversion, and that’s the project we are currently finishing.

Is the title The Sprawl a reference to William Gibson?

Not really. It’s more a reference to the notion of the proliferation of narratives and different, parallel truths, which you could say is a postmodern thing, but also a slightly spiritual thing. The Sprawl plays with and connects narratives that the West perceives as propaganda. In artistic terms, it is a combination between a documentary and a music video.

How would you define the spiritual element of propaganda?

The fight over truth is not just about presenting evidence and facts. Belief plays a strong role, even if you think that you have all the information.

And if you don’t know the truth, you have to believe. In that sense, this contemporary crisis of reality is very spiritual.

It’s not even necessary to be unaware of the truth. Even if you are fully aware of what happened, such as with the terrible events in Paris, there still is a crisis of reality. Many of us have now jumped from the belief that the war in the Middle East doesn’t happen here, to the next belief, which is that we’re at war and everything we have been doing in the Middle East bears no relation to Islamic State. Our beliefs protect us from examining our own actions and becoming transparent to ourselves.

Part two of the group exhibition “Transparencies” opens this Friday (November 20th) at the Kunstverein Nürnberg.

Credits

- Interview: Thom Bettridge