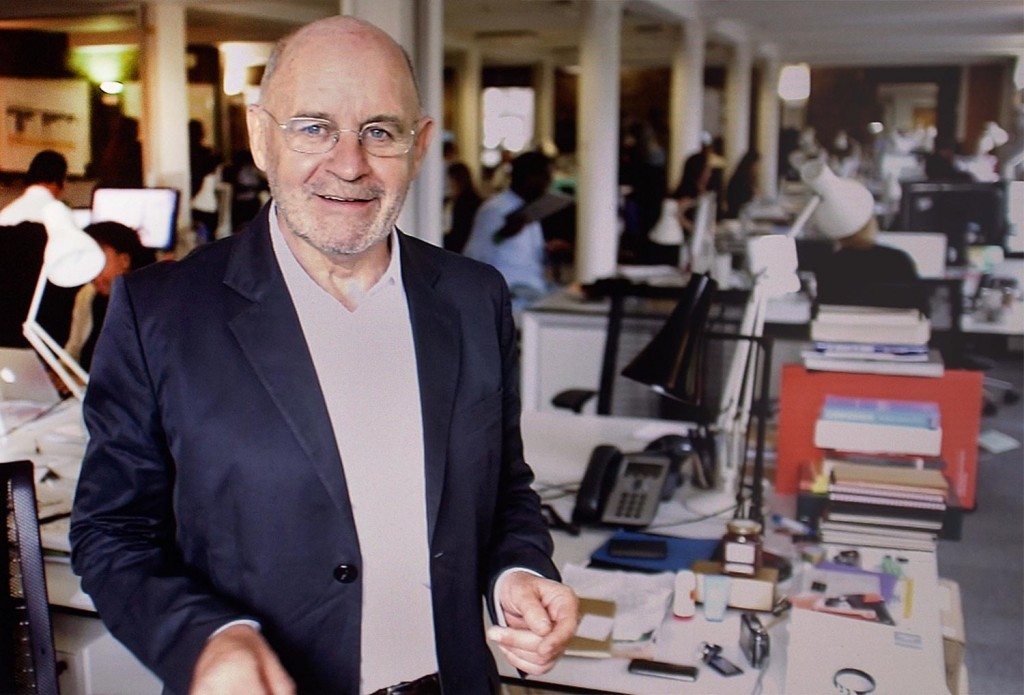

Corporate Personality: BRIAN BOYLAN @ Wolff Olins

|THOMAS DEMAND

BRIAN BOYLAN is the chairman of the legendary branding firm WOLFF OLINS. Founded in London in 1965 by Michael Wolff and Wally Olins, their first job was to create the identity for Apple Records with The Beatles. One of the entities crucially responsible for articulating branding as a discipline in its own right, Wolff Olins has created a century’s worth of influential brands: Orange, the City of New York, the 2012 Olympics, and PRODUCT(RED), among countless others. Over his 40-plus-year tenure, Boylan in particular has shaped the firm’s relationship with the art world through branding initiatives with the Tate, the Serpentine, and the Smithsonian, and through projects like Olafur Eliasson’s Little Sun (2011). For 032c, Thomas Demand discusses organizational purpose, the new pope, and artists’ diffusion brands with Boylan over a correspondence this fall. At a moment when the relationship between branding and the art world is seen through a particularly sharp lens, Boylan provides a key perspective on the bond between image and substance.

Thomas Demand: What do you think of the new pope? His new branding initiative is rather startling. Could you have done it better?

Brian Boylan: I don’t know whether his brand strategy has been developed by some smart Jesuits running the Vatican City Papal Brand Governate (using the same tools they used on me), or by Simon Fuller’s XIX (the creators of celebrity brands like the Beckhams). Either way, Brand Francis is doing pretty okay after a very short time in the marketplace.

I’ve spent most of the last 50 years avoiding Popes and Catholicism, but recently I have to say I couldn’t fail to notice Pope Francis. There seems to have been a concerted effort to promote Pope Francis, to position him as a different sort of pope. I’ve noticed that he is having an impact that has been remarked on way beyond the confines of the Catholic Church – from the Pope’s star-like acclaim from three million in Rio, the so-called papal bounce, to an increase in confessions in the UK. Plus the old French car story, which hit primetime BBC News at the same time as the recent Washington shoot-out. A series of high-profile gestures and pronouncements have made him a celebrity, paradoxically and very cleverly by making a point of avoiding markers of privilege and the trappings normally associated with celebrity, status, and fame.

He seems to be putting himself across as the People’s Pope, a “no frills” pope, with his “common touch providing the greatest inspiration.” No smart cars, no grand apartment, no ermine trimming at his coronation. Washing feet in prisons, on the side of the poor, fairness, and fair values for everyone in an unfair world, and addressing universal societal issues, not theological issues – “food waste is stealing from the poor!”

“Pope Francis, the People’s Pope, or Frank Pope, as we might know him in the future, has made a great start in getting the people on his side. The question is, will it last, and is it image or substance?”

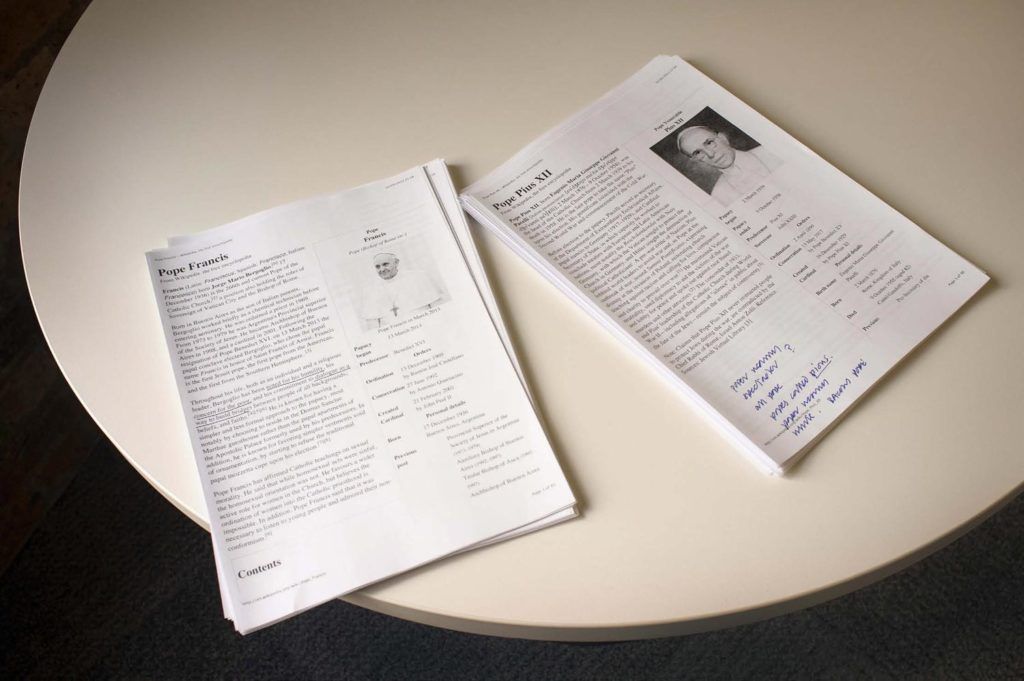

Yet it looks like it’s still the “old” Church, stuck in the past. He looks like the pope of my childhood 50 years ago, Pius XII. They all look the same and alien. Formulaically dressed in white, cross hanging from neck, imperious, transported down from heaven with worryingly benign smiles, and from time to time in spectacles. Here’s a thought: Would a cross-eyed pope ever be credible?

To make a real mark, to really move the Church forward, he has to change some of the fundamentals. Take a real-life, real-people approach to contraception, abortion, and celibacy. He could also begin to make the Church look and sound the part. Bring it into real people’s lives and into the 21st century. It still looks like a museum piece; it talks and uses the private language of theology. If his Church of the People is to succeed, he needs to make it more than his posturing as the Poor People’s Pope.

But what I find surprising is that the main change is the way he gets his message out there, which you acknowledge yourself as well. He tries to get the people first, then the institution, and he’s doing so with very iconic gestures. Of course, that was all at the beginning, but I thought the idea was strong because it’s so simple. And if I understand the idea of rebranding correctly, then the communication around the client is mainly what is targeted, right? To what extent would you counsel on the product as well, or in this case the catechism?

Targeting clients was it, and still is in many cases, but with social media you can’t restrict what you are doing, or the impact it might have. Pope Francis’s latest reported move towards the people – christened the “Cold Call Pope” – has him calling up people with some personal problem, like a death in the family, or issues with their sexuality. But what about the people who don’t get the call? And what about the probability, which apparently has already started, of someone else passing themselves off as the Pope and pissing off the Vatican, obliging them to issue denials?

More important than that, and probably more aggravating for the powers that be at Vatican HQ, is that in some of his conversations he can be way off brand. In one interview, which was kept very low profile, he said that “the moral edifice of the Church is likely to fall like a house of cards.”

So he is out there, addressing the crowds and causing a bit of commotion, putting himself closer to the people. But as an advisor I would ask, is he getting close enough to enough of them? Is he making full use of social media to reach enough of them? He has three million Twitter followers (Barack Obama has 35 million), and couldn’t he be using social media to encourage people to mobilize themselves into a grassroots, bottom-across movement? There are some 1.2 billion Catholics in this world, and even 20 percent of them would be a force to be reckoned with – if motivated and activated not by beliefs for the next world, but by actions for the world now.

Pope Francis, the People’s Pope, or Frank Pope as we might know him in the future, has made a great start in getting the people on his side. The question is, will it last, will he last, and is it image or substance? People’s Pope is simple, but to work, it has to take us much further than this first flush of iconic gestures.

Substance versus image, that’s a rather interesting dichotomy. I always prefer image, because it becomes substantial after a while. That’s the miracle of art, and presumably that’s why religion liked us for centuries as well, at least from an outsider’s point of view. As an insider in the arts, what do you think this approach would mean concerning the noise around the arts? Shall I wash Roman Abramovich’s feet? Or, more seriously, if I understand you correctly, you are trying to practice your part in the most uncynical way thinkable, aren’t you? So the branding around the arts probably appears to be market-friendly, but for the artist, it’s a fundamental decision about life and one’s attitude towards it.

Substance versus image: a similar challenge we both face in what we do. You prefer image; I lean towards substance recognizing the importance of image. You create images in a true sense – tactile works of art; we produce them in a less tactile, more diffuse sense – image as a broader church, from reputation to looks to experience.

In art, you are right: The image is the substance. But in what we do, working with brand and brands, the substance is becoming increasingly and critically important. Which is why I banged on about the Pope earlier. People are going beyond the veneer. The successful brands today are those that enable folks to do things – as well as to look good and make you feel good. Utility is essential. Image has to help deliver the utility and, of course, the commercial value. In that respect we consider and create image as a means to an end – not the end in itself, whereas for the artist the work is the end.

Touché! The work is the end, my friend. That’s awful news. You think branded communication could be helpful here?

Some of that commercial stuff has steadily and forcefully crept into the art world. (But that’s not new – money was always around.) It is a market, in fact, many markets. Some artists are brands, even global brands, and their brands and images are carefully nurtured, consciously or otherwise. Art is big business. But does that mean that artists are now market-facing, or, as you put it, market-friendly? I don’t think they are. Most of those I know just do what they do; but I can’t help feeling all artists are now much more market aware, and some are even market-making, and making the most of the brand tool to do that, although they might be reluctant to admit it. (Brand still appears to be a dirty word in the art world!) Damien Hirst is a brand – his “Spot Paintings,” and to a lesser extent his “Spin Paintings,” are his diffusion line brands. “Other Criteria” is his curatorial/shop brand, a.k.a. a brand-led business, or an artist doing a serious series of different works. What drives this? The artist’s desire to get more of his or her work into the world, in the market, so to speak? Or to gain more market value?

We are such a niche-niche; if someone gets his work into the real world, that’s already quite remarkable. Doug Aitken just did this three-week tour with a train throughout the States, and there I recognized the possibility of getting the two ends together somehow. Levi’s was the sponsor, which in a way probably makes a lot of sense for them. Did you advise them? Would you? And how do you choose your clients?

“If MoMA were a person, would he or she sit in a wheelchair in 50 years? Long beard? Plastic surgery? Pondering about its lost marbles?”

I had noticed Station to Station and thought it looked great. It gets the art out there, it gets Levi’s out there with some very good art and culture brands, and Levi’s is a good brand with a lot of credibility and a broad audience to do it with – and the economic clout too.

We didn’t work with them – but would have loved to. Choosing and getting who to partner with is difficult, not just in getting the right brand partner, but in getting the whole notion of art sponsorship out of the boardroom. This has less to do with reputation and entertaining and more to do with engagement.

Some others artists and corporations are doing it – Jeremy Deller’s Sacrilege, which visited 32 cities cities and towns; BMW Guggenheim Lab; and even UBS’s MAP initiative. So that’s a good example of getting it out.

So far our work has concentrated on getting people outside in, and getting people on the inside onboard. What drives us is getting more uptake of who and whatever we are working with to create curiosity, interest, desire – but all of that driven by an idea – the purpose of the enterprise we are working with. A purpose that can be shared with customers, employees, and partners. Our role in all of this is to create a clear, compelling articulation of that purpose – big, simple, and true – and then give that a very distinctive form and voice.

Articulation … hmm. It sounds like if a brand were a single person, you would teach him or her how to speak, not what to say. What else? What not to wear? Manners? Can one call a brand a corporate personality?

You certainly could call a brand a corporate personality. In fact, in the early days of Wolff Olins – the 1970s – Wally Olins, my predecessor, penned a book called The Corporate Personality (1978), which was to explain the theory (if it existed) of what we did then. Today I think what we do is much more than personality. It engages with purpose. And we don’t teach. We try as much as possible to co-make with our clients, advising and influencing, stimulating as much as possible. More direction than dictation. These days brands have to flex, but not deviate.

But if that personality flexes too much it can overstretch the attention muscles of the audience. Like with the 2012 Olympics. That concept got a kind of sore welcome, no? Was it too complex?

Complex maybe; controversial for sure. A little painful at the time. It certainly was much more than the conventionally practiced Olympic identity – a stylized national stereotype or an athletic gesture meeting an iconic building, with the city name and date sitting on top of the Olympic rings.

The London 2012 bid was won on the promise of extraordinary levels of participation (not watching), especially for young people. These were to be Everyone’s Olympics: Everyone Olympic (our words), with culture playing a critical and integral part as originally envisaged in the modern Olympics. The Paralympics were to be fully integrated, too. Both for the first time.

“Brands are organizations, and like organisms, they are alive, they have to be able to change and morph. Today more than ever our challenge is defining the limits of change, and prescribing systems that permit change.”

These were to be Olympics like never before: off the pedestal, out of the stadium, into the streets. Join in, take part, play your part, lasting not just the few weeks’ games period, but also the four years before, and hopefully long after.

In these respects they were more complex and more challenging and in our view more demanding of people to fundamentally reconsider the Olympics, to see it not as an event, but more a way of behaving. Our premise was to create 2012 as a brand to do that. Not the London Olympics, but 2012, connecting the games with the normal sponsorship initiatives and with a whole range of cultural and social activities taking place outside the games. That had never been done before, but we pushed to go beyond that, to permit everyone to be able to create their own version of 2012. For Everyone’s Olympics, everyone has their own version of the brand.

All of that resulted in the mark based on the numbers 2 0 1 2 – a disjointed, disconcerting, hollow form that could be filled to suit. The Olympic rings TM could be removed to overcome restrictions on widespread use. Something that everyone could use. On reflection I don’t think it was too complex. A “fill-in, make-your-own-version” logo is a very simple notion. When it launched it wasn’t explained like that, and it wasn’t liked either – by Daily Mail and Daily Design. The trademark lawyers restricted its use to the games, the sponsors, the countries, and the cultural initiatives, saying that widespread use would reduce its commercial value!

So, sadly it did not get to be used by the people it was meant for. Although some did break the rules, I’m glad to see and say.

Coming back to your expertise within the art world, you introduce a distinctive brand or reinvent a platform for an institution, no? You just said in a way that you are beyond surface, which I’d like to get an example of. If you, for instance, relaunch a new museum, what’s your contribution to the content-building? Can you talk about it?

We have done some work in the art world and I can explain what I mean by below, beyond, behind surface. Tate is a good example. When Tate commissioned the TGMA building, it wasn’t clear what it was to be or where it would sit in the world or fit in the world of Tate.

Working with Tate’s top team, we helped them define a clear purpose – “Democratizing Access to Art”: articulating its way of thinking, breaking out of the straightjackets of convention thinking, which we summed up as “Look Again, Think Again,” a challenge to staff and public. And finally that Tate would have perspectives, not doctrines: “Always Changing, Always Tate.”

All three of these manifest themselves in the way Tate is, as well as the way it looks. The non-chronological hangs are rooted in “Look Again, Think Again.”

Tate Modern is shorthand for Tate’s particular perspective on modern, and the many versions of the logo – 60 – is a manifestation of “Always changing, Always Tate.”

The particular look – bold font, bright colors, and sharp language – and dropping the “The” from “The Tate” take it out of the institutional world of The National Gallery and place it firmly as a brand alongside Selfridges. Off the museum pedestal and onto the streets. Not to everyone’s liking.

So the iconic forms we created for Tate didn’t come from design and the design world, or art and the art world, but from a need to help Tate realize its ambitions in and for a wider world. Has it? Or has it just got the numbers up?

Well, for sure it widened the standard set of options for the suburban dweller for what to do on a rainy weekend. When I lived in London in the early 1990s it seemed all rather dire – either you went to go watch football, shopped in the same chain stores, or got drunk somewhere. Then the lottery was introduced.

The impact has been much more dramatic than we, or Tate, could have imagined, but it’s what we had hoped for. It also set the scene and paved the way for other cultural institutions in London and across the world to take to brand. (“But let’s not use the “b” word, it will upset our trustees.”) We worked in Europe and the US – for institutions like Schaulager and New Museum and Smithsonian, and on a global level and a broader cultural level for the 2012 Olympics, where 2012 was to be the brand, not just the date!

We – me and the great designer Marina Willer, who had done Tate with me – recently returned to London to help Serpentine, which you personally know well. It’s a similar situation to Tate: They’re also getting another building – the Zaha Hadid-designed former Magazine (in a military sense) building. It’s similar also in that it provokes the need and creates the opportunity for Serpentine to assess, redefine, and assert its place in the world. So a similar approach – inside-out – requiring not just a new logo, but a clear idea of what Serpentine stands for, how it could deliver that, and how we wanted people – the public, artists, and collaborators – to think about it.

Working for more than a year with the two directors, we defined Serpentine as one, not two, with the purpose of “Opening Out Art” – continuing to extend the boundaries, introducing

New Forms (such as architecture, film, performance art, dance, writing, science), developing New Formats from the interplay between these forms, and creating New Ways by stimulating the interplay between artists, audiences, and spaces. The specially commissioned monthly audio stories, timed to be listened to as you walk from one gallery to the other, are a good example of this.

We describe Serpentine as “An Open Landscape for Art,” picking up on both its “Opening Out” idea and its very special location in a park in the heart of London. The brand identity we created manifests that. Inserted in the new Serpentine logo is an aperture – the opening into the landscape, varying in position and width depending on the requirements or whims of artists or designers. The aperture idea extends to create fields, ideal for digital.

I looked at it and I think I get it, even if I am not sure about the disruption of that beautiful word Serpentine, very unique and never really explained for this context. I think it works best when the insert is moving into different places, if the signage isn’t static but changes for each of its appearances.

It is intended to be used in different positions – that is the whole point. And I think that over time it will be recognized as one whole – including the insertions, and not as the current word broken in two.

As you say, there is a natural tendency to get used to things over time. Do especially monumental successes like Tate wear the brand out to an extent? Are you still advising them? Or is there a Tate 2.0 level of handling the brand, which was part of the original plan? Was it a launch, or more of a peripatetic, morphing strategy?

It is not just that you get used to things – maybe we take them for granted – but that circumstances change. Brands are organizations, and like organisms, they are alive, they have to be able to change and morph. Today more than ever our challenge is to define the limits of change, and to prescribe systems that permit change.

We did work for Tate on an ongoing basis for 10 years and moved on to the focus of the defining purpose and the way it looks, and there is a possibility that we might re-engage around the impact of the new Tate Modern extension. Increasingly we see brand as a journey with intention, not a destination, and we look forward to long collaborations with our clients.

Do you think a cultural institution needs to present itself as a brand at all? I guess that any guerilla attitude would work for a while, but then once tradition comes into play it might need to contemplate how to get the freshness together with their own history. Or is my notion too paralyzed about being manipulated, and actually every player in the public is to a certain extent a brand? Is there only good and bad brand management?

The point you are making about a guerilla attitude is unclear to me, but in response to your last question – every player in the public arena isn’t necessarily a brand, nor should they be, but many could use the techniques of brand to enhance their social impact – and that they certainly should do.

What I mean by a guerilla attitude is an unorganized, unsustainable, and inconsistent appearance, like Experimental Jetset tried a couple of years ago, or actually one that any small artist-run space tries to set up. Though Tate, Serpentine, and the Smithsonian are established institutions. Any advice for the unorganized, underfunded, and desperately understaffed stint?

Advice to the under-everything organizations would be to just go for it. As you can see from my ramblings – it is not rocket science, and there are lots of very smart, very creative people (much smarter than we old-timers are) out there dying for the opportunity to do something. Also, some very small organizations already do it well. Chisenhale, for example, has great brand and brilliant identity with virtually no money at all.

What do you think the museum will look like in, say, 50 years? If MoMA were a person, would he or she sit in a wheelchair? Long beard? Plastic surgery? Pondering about its lost marbles?

It’s impossible to say looking at the changes over the last 15–20 years. My hope would be that well before your 50 years is up museums reestablish a dominant position in the art world – which is currently dominated by the market forces of galleries, auction houses, art fairs, and of course just money. That $uper tanker will be hard to turn around.

For MoMA in 2613, there are a couple of choices: to continue as is, dominated by 20th-century modern and become MoMAfied. Still worth a visit to see some of the great treasures of the 20th century, but a historical museum. More likely, it will have been injected with a magical brand-rejuvenation drug that will have given it a new lease on life, new focus, new energy, new blood in its veins, and the wherewithal to flirt with, attract, and take on the bright young things of the 21st century.

Credits

- Text: THOMAS DEMAND

- Photography: ROBI RODRIGUEZ