MATT LAMBERT: Pleasure Park

|IRINA BACONSKY

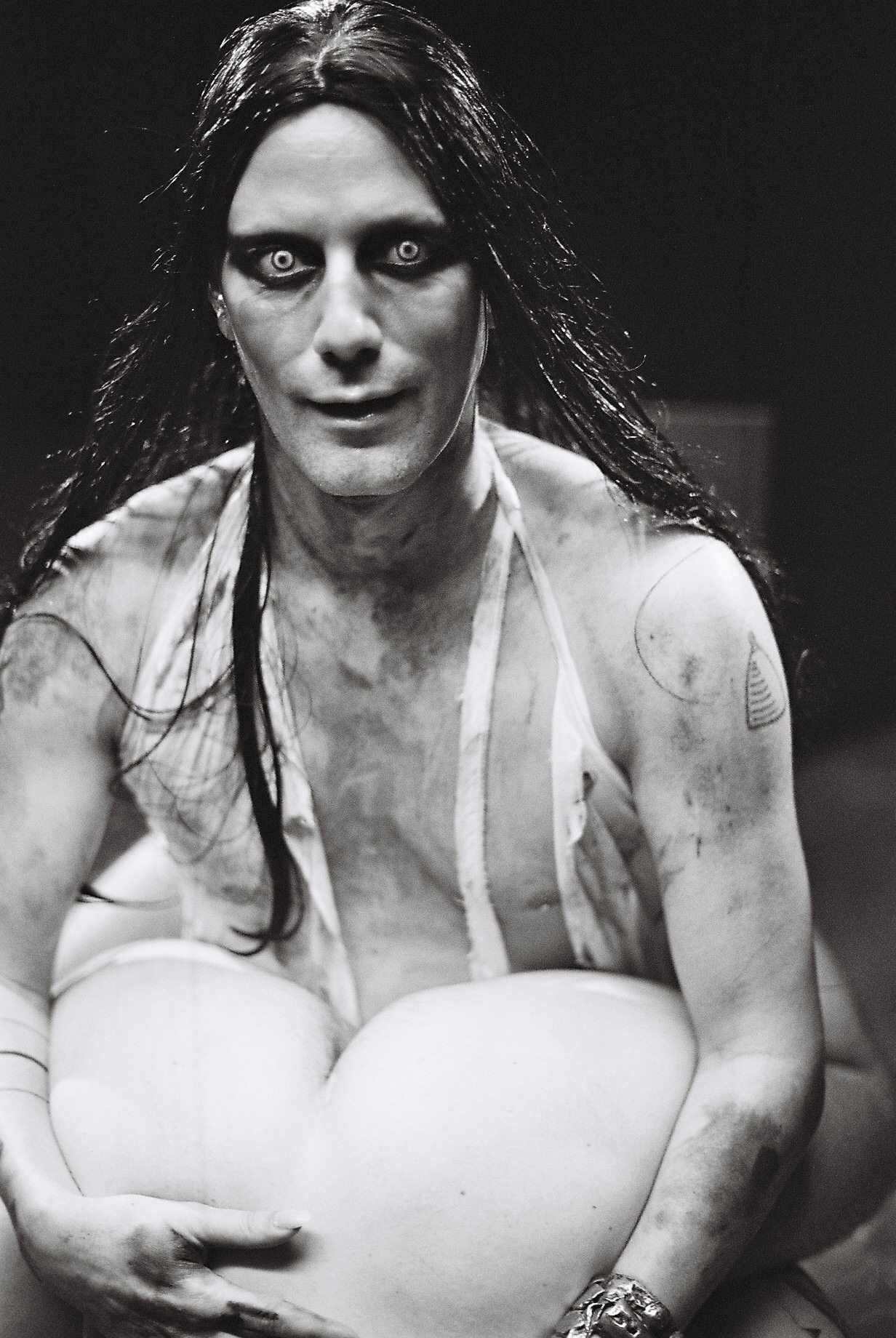

“The world of the heterosexual is a sick and boring life,” states Edith Massey in Female Trouble, John Waters’ 1974 brazen classic of grotesque comedy. A long history of analogue playful, punk, or personal artistic takes on sexual identity have contributed to chiseling a prism of queer aesthetics, which Berlin-based filmmaker and photographer Matt Lambert inhabits with his new project, Pleasure Park, a collaboration with porn studio men.com and the Tom of Finland Foundation.

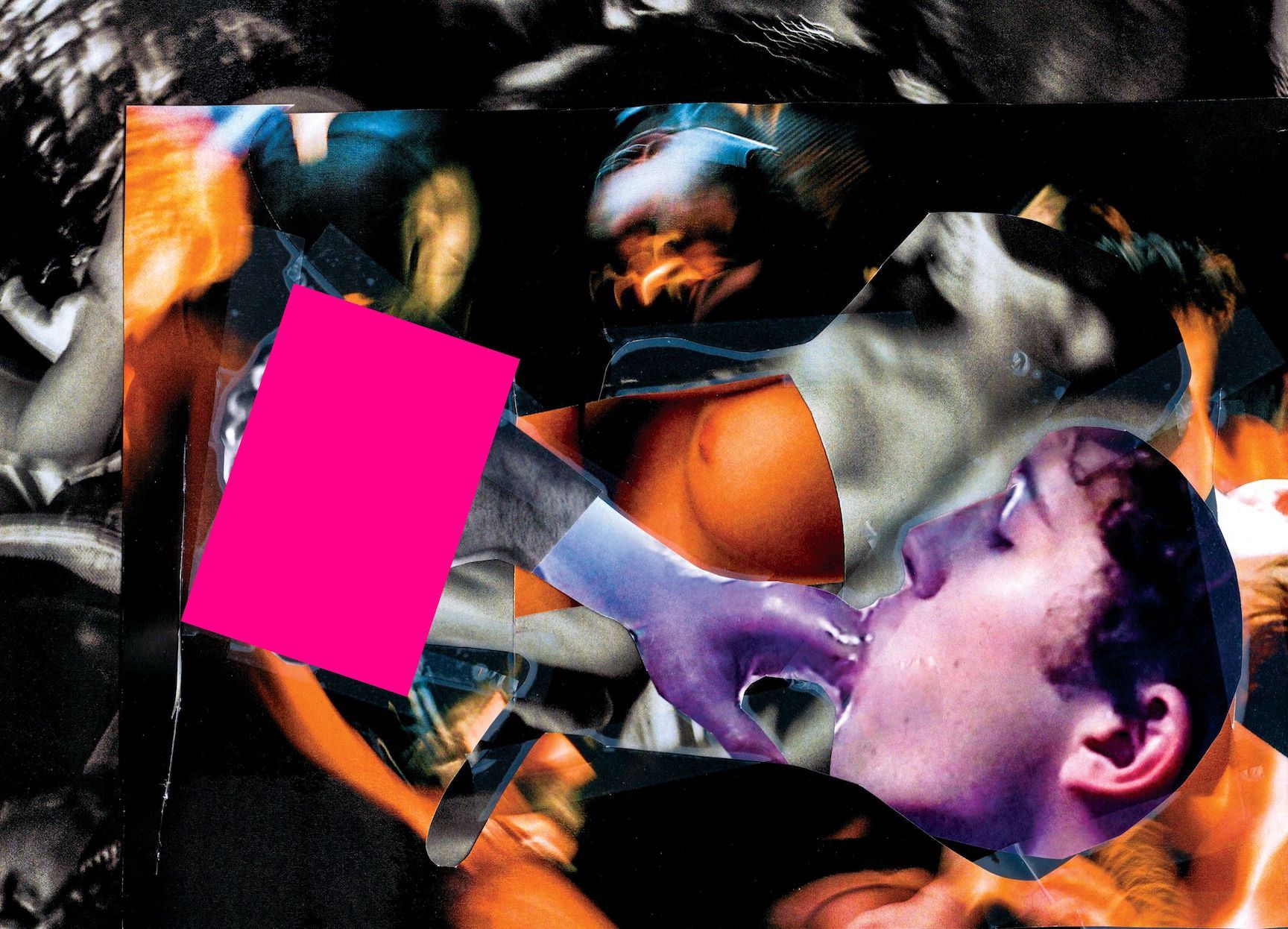

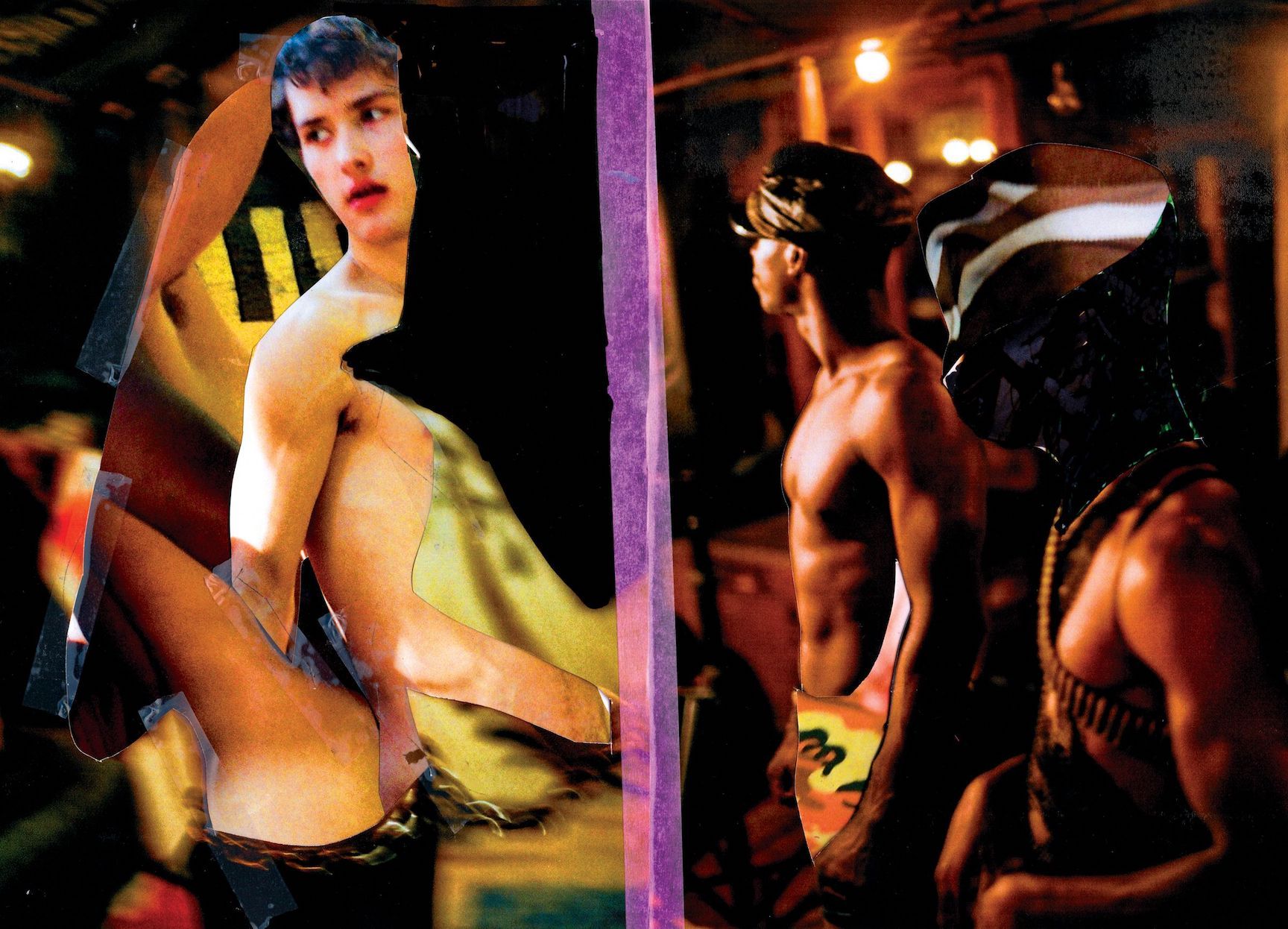

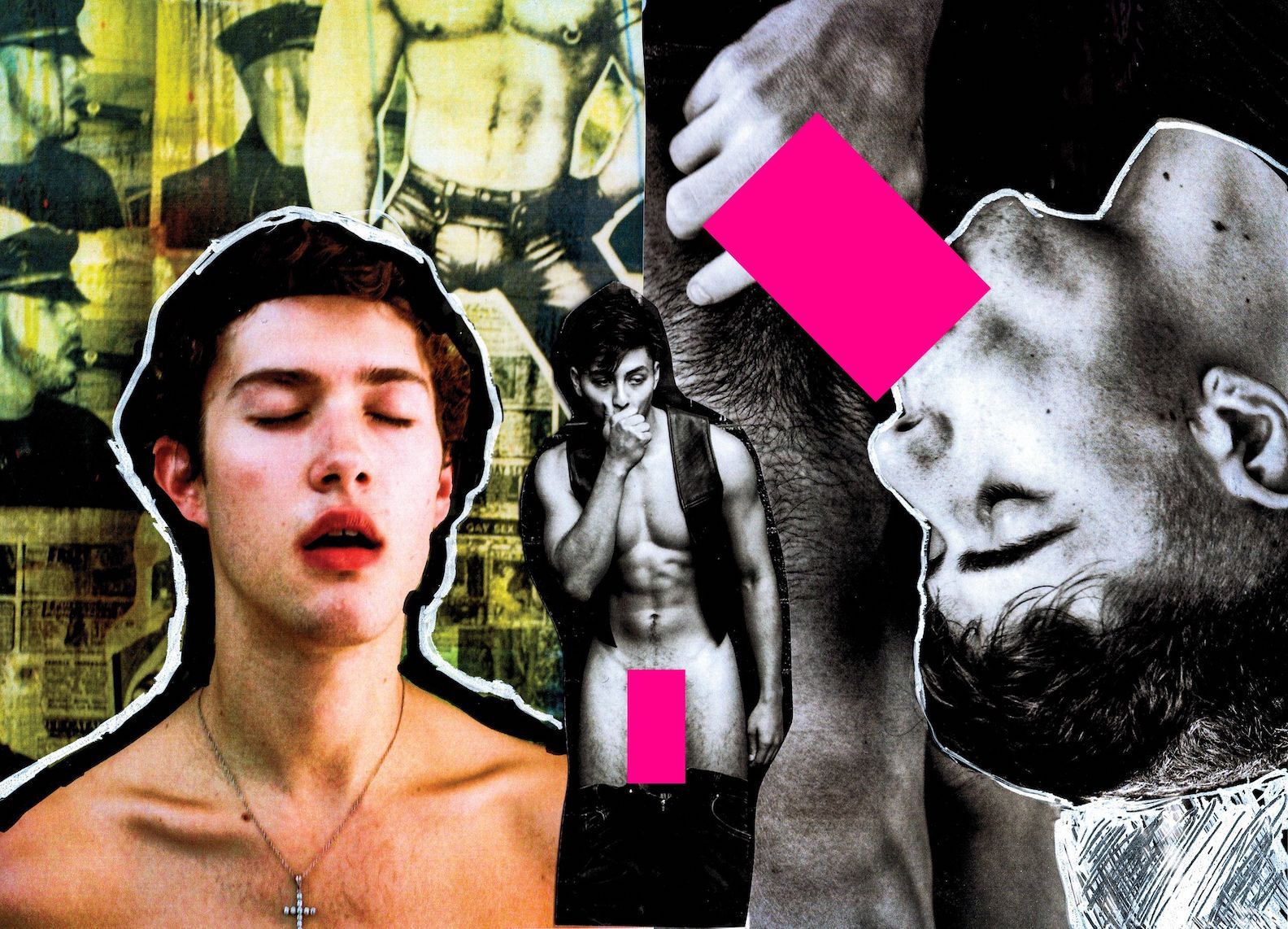

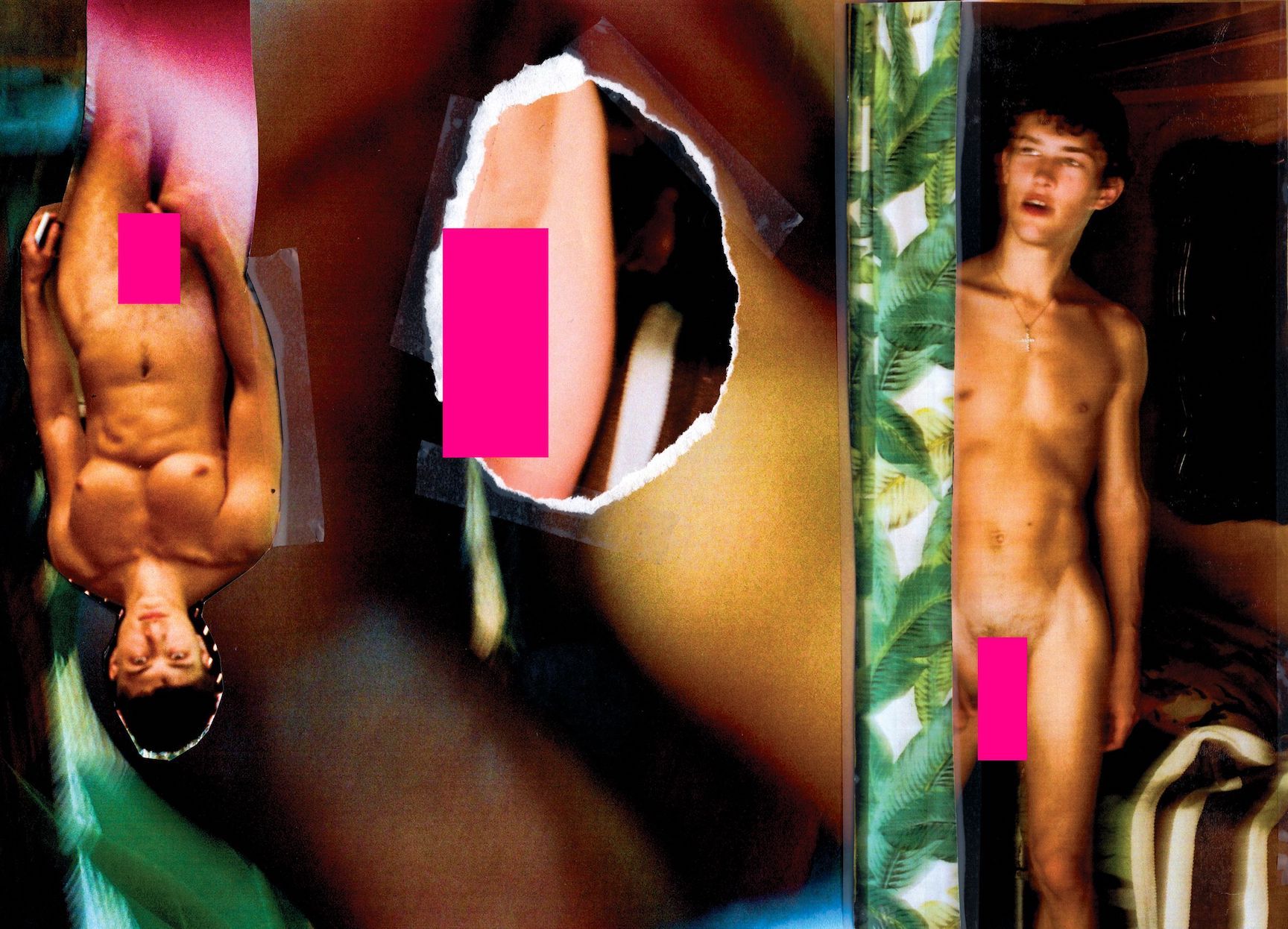

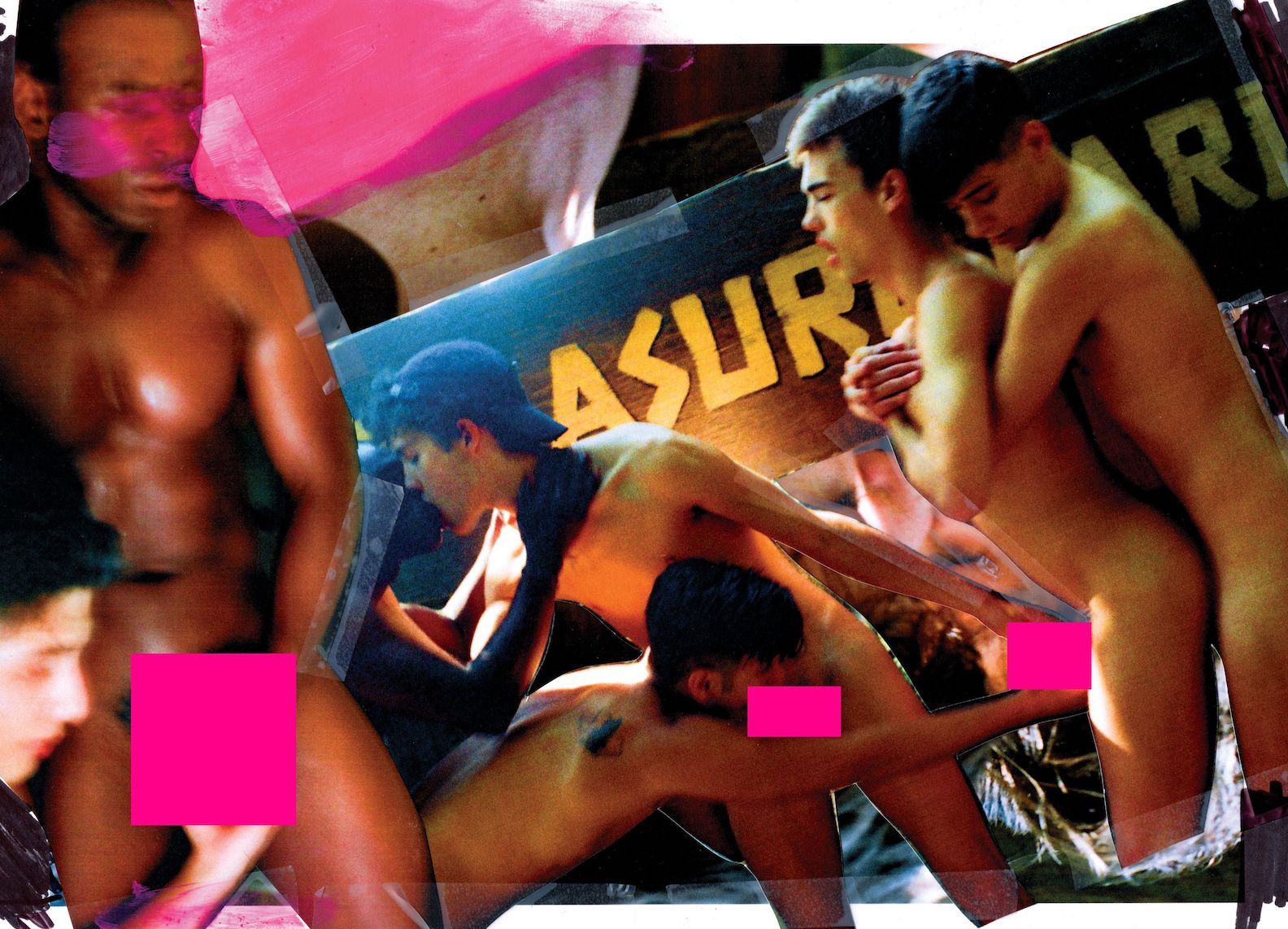

Shot over one summer day at Finland’s former house and visually nodding to the forefather of homoerotic illustration, Pleasure Park is a collage – a jigsaw of soft-core images featuring a group of friends and adult performers – to be released in early 2020 both as a film and a zine with illustrations and graphic design by Berlin legend, Stefan Fähler. Ahead of the zine’s pop-up launch, we asked Lambert to revisit the progressive and subconscious fashioning of his photographic lens.

Irinia Baconsky: How did the premise of Pleasure Park emerge?

Matt Lambert: This project is many things at once, but it started as a film. I tend to do one explicit film a year, and this year I was approached by Men.com who were doing a collaboration with the Tom of Finland Foundation. I made a film that is set in the present day but has a nostalgic timelessness to it, all shot in one day at Tom’s former home which is now the Tom of Finland Foundation. The photographs shot parallel to the film are what led to the Pleasure Park zine – my fifth publishing project and a follow up to Vitium, a zine I made with my husband, Jannis.

How does Pleasure Park flow from Vitium?

Vitium was an homage to queercore publishing. I grew up in LA and was obsessed with punk, but in spite of this love affair I had with it, it’s something that I felt subconsciously excluded from. It wasn’t until later, when I discovered the queer punk movement, that I realized there was a place for me to exist in that world, and that being a faggot was punk as fuck. So Vitium was a sort of homage to that queercore and homocore movement, to mentors and inspirations like Bruce LaBruce, Peter Berlin, Pansy Division and such. Pleasure Park is just a continuation of that, it’s me re-contextualizing and revisiting my youth through the lens of a homopunk aesthetic — one that I wish I’d had, and wish I’d known existed right beneath my nose while I was growing up.

Pleasure Park is a film and also a zine. You made the zine a series of collages. What draws you to collage?

There’s a looseness and a spontaneity that comes across in the film, and in the energy of the people in it. There’s a found-footage, documentary feel to it all — like a relic that’s been unearthed. I liked this idea of this body of work feeling like an archive, a collection of moments, something homemade. The collage creates this archival, yet spontaneous feeling that made sense and the punk gig posters hanging in LA in the 1990s was one of the first aesthetics I fell in love with as a kid.

This sense of effortlessness is also personified by the stars of the project. How did you choose your subjects?

Some of them are friends; others, former collaborators. It was important to create an atmosphere with performers who were honest, effortless and didn’t come off as overly self-aware which isn’t always easy to find when working with people who have lots of adult film experience — they can become overly performative and forget what natural intimacy is supposed to look like on-camera.

You knowing them perhaps also contributed to creating this relaxed, intimate atmosphere.

For sure. The moments were constructed, but they were also very honest and real and never felt forced. It’s something in between constructed and documented.

The shooting took place at the house where Tom of Finland, one of the biggest references when it comes to homoerotic art, used to live. Who else inspires you?

For this project, a lot of it is subconsciously referencing punk aesthetics, films like The Decline of Western Civilization, chronicles of the punk scene. But the style was also born out of necessity, and wanting to have a small crew. The lo-fi aesthetic was a choice but also a necessity as is often the way when I shoot projects like that.

How has your take on queer or male intimacy evolved over the years?

For many people around the world, especially queer people, porn is very often the first way for them to engage with ideas of sexuality and intimacy. I’m by no means trying to make “educational porn,” but rather work that shows a more playful and humanistic form of intimacy that’s not necessarily reduced to sex – sex is obviously a big part of the conversation, but for me, becoming more aware of the politics behind what I’m doing changed my perspective, thinking about how queer young adults will engage with my work and how that could potentially offer them an alternative to what’s out there — one that’s celebratory and humorous, awkward and authentic. People like Erika Lust, an amazing Barcelona-based feminist porn director, are definitely changing the conversation, alongside countless other independent queer filmmakers. It’s not that we’re bound to be educators when we make this kind of work, but I do feel we have a responsibility to show a different perspective — one that explores intimacy in its many forms and not just reductionist sex.

Looking back on your work, Vitium was a more overt “fuck you” to heteronormativity, whereas Pleasure Park is conveying the same message in a more subtle way. Showing alternative ways of building intimacy can be a strong political statement in itself, even without the “aggressive” aesthetics.

Sean Ford and I had a conversation about the looming end of the world and how we’re living our lives with this sense of pre-apocalyptic doom looming over our shoulders. So in a way, the film is a nihilistic celebration of being true to yourself and feeling free in your own skin now. Because, what if the world ended tomorrow?

You speak of porn as most people’s first interaction with the notion of sexuality, but pornography itself is rarely seen as art. Do you think porn has the potential to be an art form?

For me, the word pornography can be really problematic and exhausting. I like to assert that my work is not porn, but of course when I do collaborations with porn studios it becomes a bit tricky. It’s different when I do a fashion collaboration like the one I did with Rick Owens – I can somehow get away with someone fisting themselves, but the context is what changes things a lot. For me, pornography is very reductionist as a word, because it’s loaded with an element of excess and over-indulgence. With my work generally and Pleasure Park specifically, I’d like to think that I make art or experimental films that have explicit content without being “pornographic.”

So in a way, you see porn as an inevitable compromise on artistic integrity.

The artistic integrity is often undermined when work starts to be made for commercial purposes, and porn is primarily a commercial commodity. It’s produced and consumed very quickly, so aesthetics are rarely part of the conversation. It’s also irrelevant if the connection between its performers is authentic, nor is that the focus.

How do you feel about people masturbating to your work?

I love that people can do that. But I also love the idea of enabling and empowering them to build a connection with each other. When Flower came out, this porn blog reviewed it by saying something like “this doesn’t make me want to jerk off, it makes me want to go and live out a sexual fantasy.” That’s kind of a cool thing, making aspirational explicit content. It’s a pretty cheap trick to get someone aroused, at the end of the day. It’s a much more interesting challenge to get someone to rethink the way they engage intimately and sexually with the world around them.

Credits

- Text: IRINA BACONSKY

- Talent: SEAN FORD, JOEY MILLS, ANGEL RIVERS, RIVER WILSON, TANNOR REED