Brenda’s Business with Fabio Piras

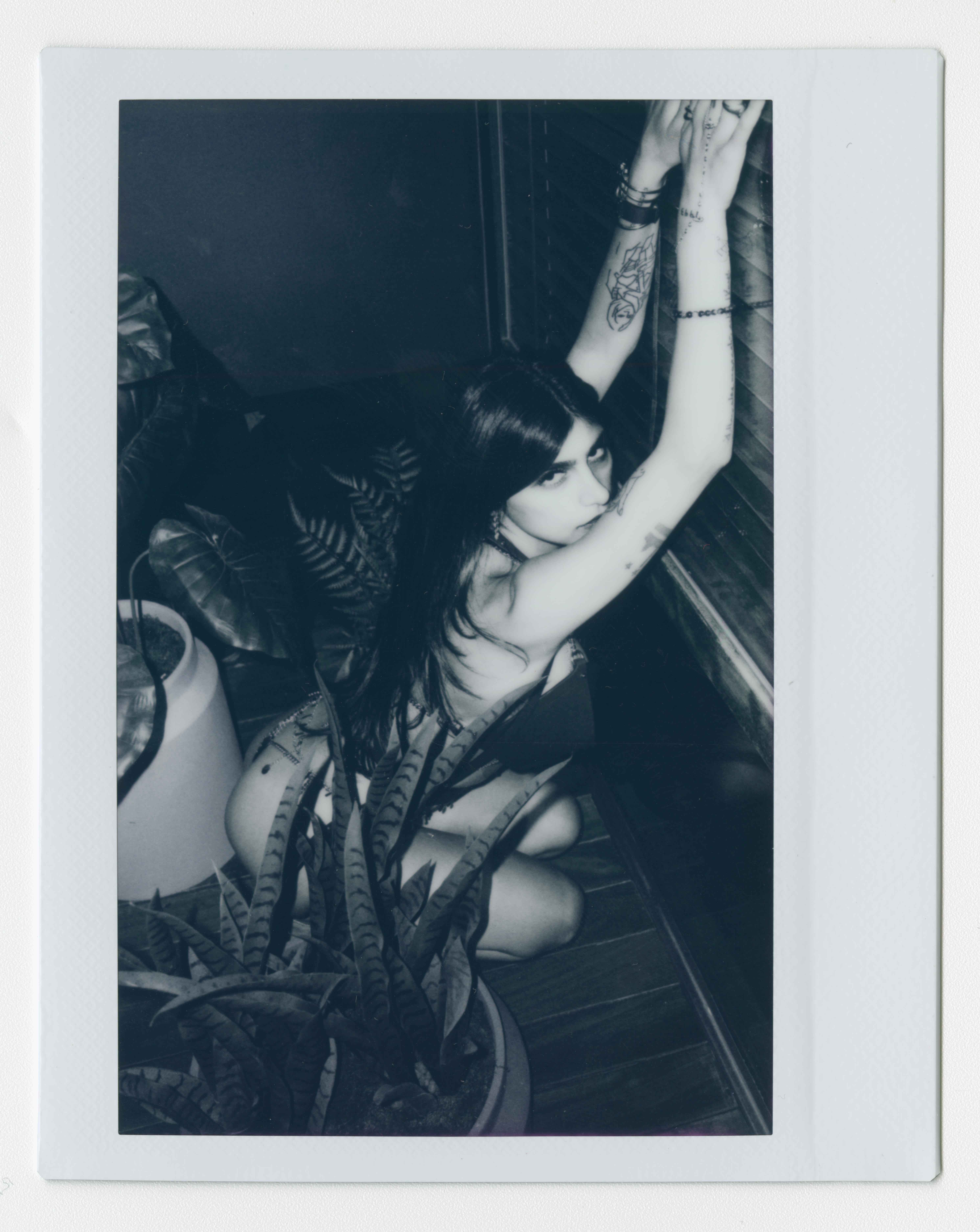

|BRENDA WEISCHER

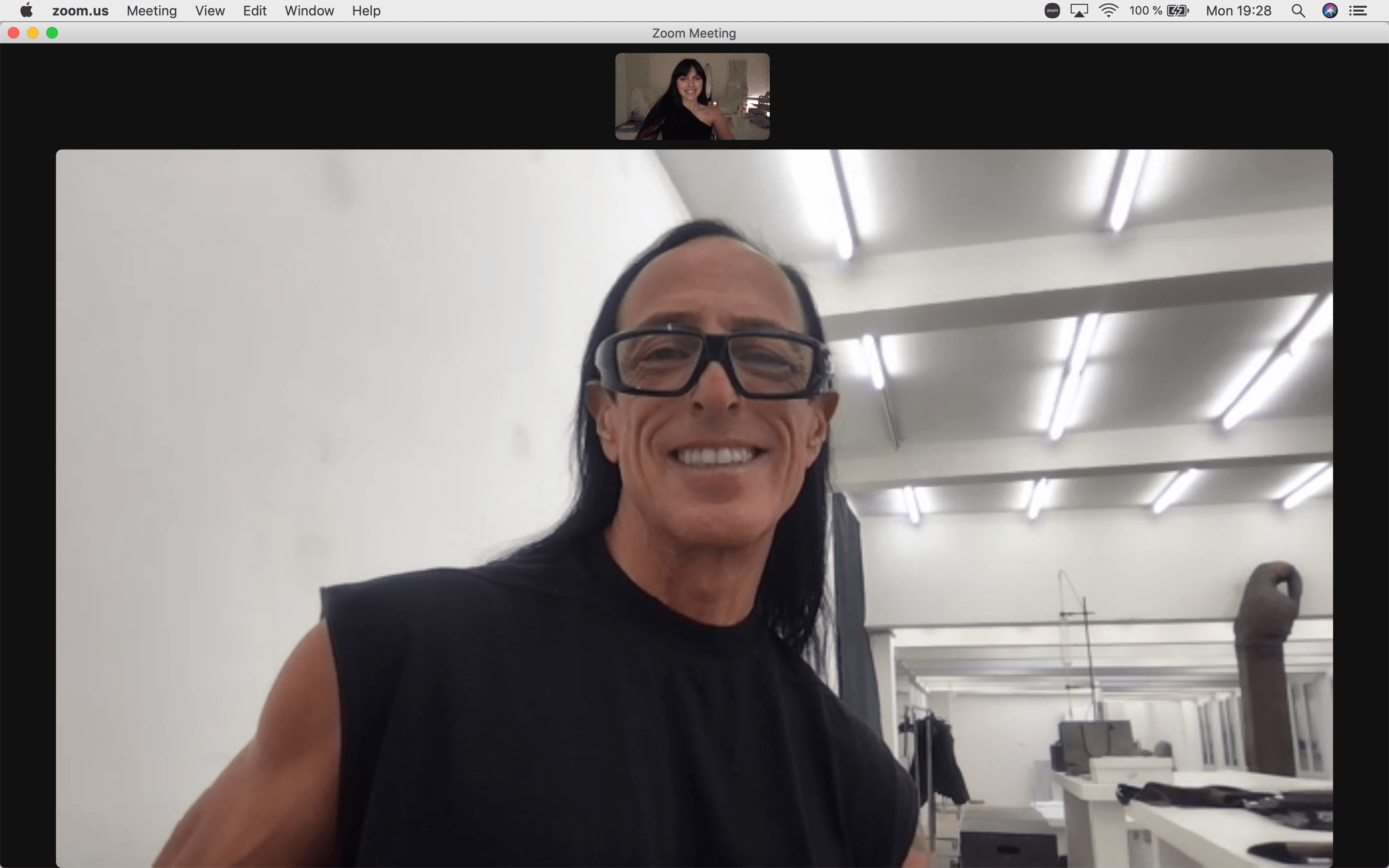

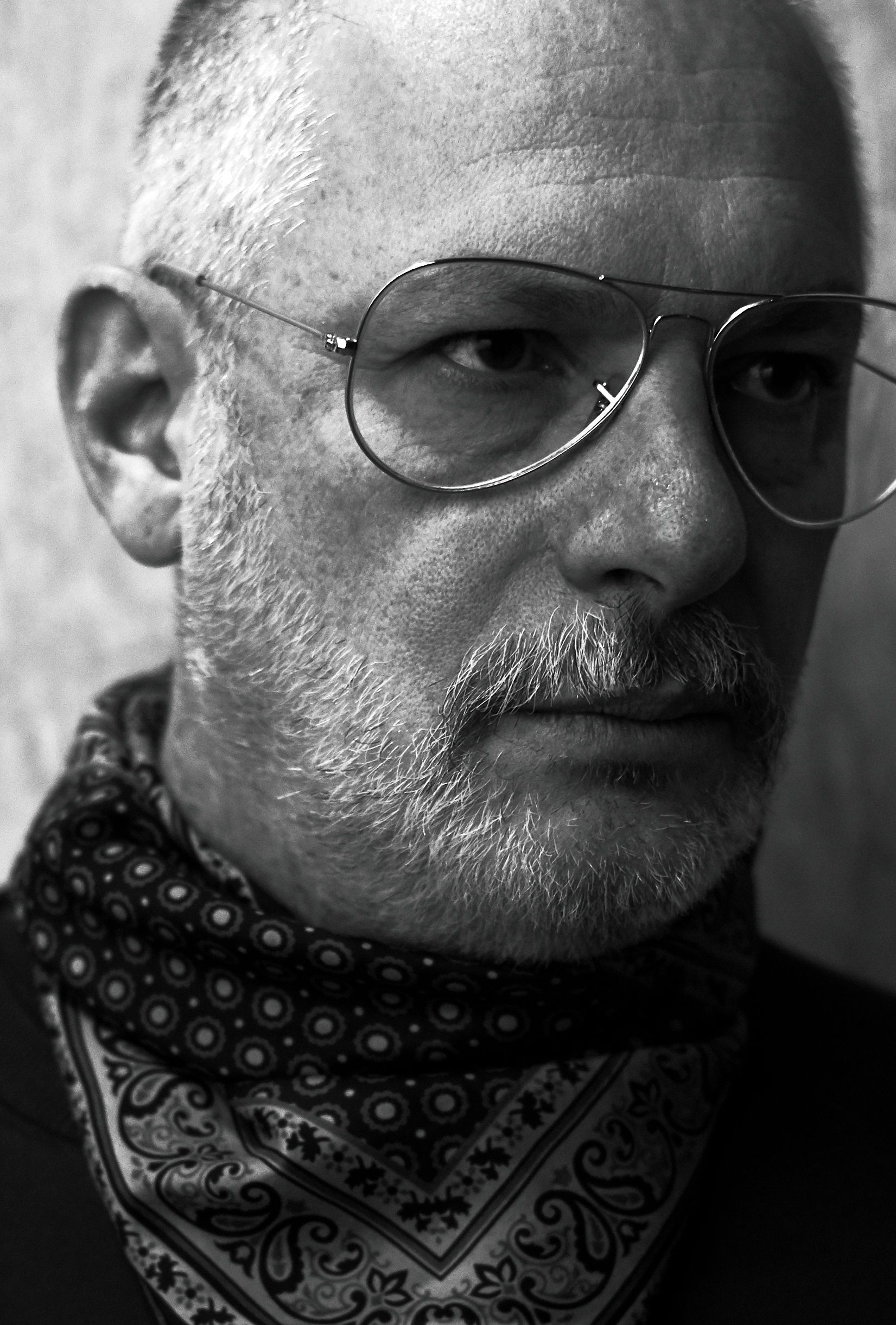

I wish I took a sneaky picture of Fabio Piras’ office while we conducted the interview for this edition of Brenda’s Business. Picture the office of a fashion professor at Hogwarts. Images plastered all over the walls, signed cards, catalogs, fashion books, even his water carafe is a design object. And why wouldn’t it be. Piras is the course director of the infamous MA fashion course at Central Saint Martins in London.

Listing all the stars who have come out of the school’s program without missing anyone is difficult, so here are just a few: Alexander McQueen, John Galliano, Phoebe Philo, Charlotte Knowles, Kim Jones, Craig Green, Daniel Lee, Kiko Kostadinov. Piras himself is also a graduate of the MA course.

In what follows, Fabio talks to me about being an institution, the nerve-racking application process for students, and why one should apply even without having the necessary funds. The university lists 13 scholarships on the course preview of its website alone. If there is a will, there is a way?

BRENDA WEISCHER: Fabio, how long have you been at your position now?

FABIO PIRAS: In this position since 2014, so almost ten years.

BW: You’re sitting at the helm of the one degree that a lot of aspiring fashion designers want to graduate from. There have never been more eyes on the fashion industry. Same with Fashion Week. Everyone wants to go. The shows are getting bigger. Information is more accessible, people are googling, “What did this designer study?” I am sure applications at Central Saint Martins are at an all-time high.

FP: They are. But there come concerns with that. You know, I’m concerned that sometimes you become this kind of institution within the institution of fashion. And it’s worrying when you become this institution. You become a brand.

I’m not that concerned about the perception that the industry has of us but I’m very concerned about the perception that potential students may have of us. Are we a platform to fashion stardom? The fashion X factor? If that’s what we are, then that’s concerning. And we can’t deny the fact that we’ve been quite active participants in this hype. Of course, it would be foolish of me to say, “Oh my God, what’s happened to us?” We advertise with our successes, we’re very proud of them. But it’s a fine line.

The genesis is 1992, McQueen. And there’s not a single year that didn’t produce somebody who made a mark. What are the expectations of the students who come here? To establish themselves as people that could contribute to fashion. And they might come here with delusional or fantastic plans that might be naïve. I think they should always be naïve to start with. It’s quite good to not know what the context of your future is.

BW: I agree.

FP: I don’t think that the priority is, “How are we going to save the world by doing fashion?” However, that needs to be on our agenda, too. How are we going to respond to current issues and current emergencies and how are we accountable? And that is obviously what makes the course (MA in Fashion) renew itself. We are proactively connected to the fashion industry. Our job is to also criticize that connection but we have to find positivity within that criticism. It’s not a rejection, it’s an awareness of what we are associated with.

BW: If applications are at an all-time high, are there also more job opportunities? I think as an outsider you might assume that conglomerates such as LVMH come straight to Central Saint Martins to hand out jobs. What do you observe, recruitment wise? Or do young designers become big on social media without needing the “institution” anymore?

FP: This is a loaded question, isn’t it? There are three sides. There’s the student, there’s the school, and there’s the job. We are not in the era where brands just come here and hand out jobs. This idea that you come onto this course today and you get a job straight away at the highest levels of fashion, in these times, I would be lying if I endorsed this. We are fully aware of this. There are enormously more fashion graduates out there than the professional employment space that is available. It’s not always easy, for all sorts of reasons. Employment laws, in Europe for instance. You always have to start with an internship because that’s easier to process as an initial contract. Then, there’s the fact that we live with Brexit here. If it was difficult for postgraduate students to get into an internship in Europe before, it’s almost impossible now. And, the fashion industry has become very accustomed to the idea of internships. When students are able to put their foot in the door, it’s very rare that that foot doesn’t move forward inside beyond that door.

BW: Right. That was my experience, too.

FP: But then you can’t pretend that all the students have the same kind of commitment to their work, to their future as designers in the industry. There’s a lot of fear of joining the industry, of what’s demanded of you—of what’s not demanded of you, too, actually. Six years of education to then sit in front of the computer to do some stuff that does not really value what you can actually do. The students want the creative side of it. So, they choose the alternative.

BW: What’s the alternative?

FP: The alternative is to start your own thing, to get together with other people, maybe to work for a brand that can’t pay you, or not at all what they should, but then you’re an equal partner in it. It’s super hard to start your own project, but it has and brings great value, and the income doesn’t necessarily have to come from the business of producing and wholesaling, it can come from different places today.

BW: Do you also get business advice here in the MA course? Do you tell the students that there are different ways of income? Or is it only about craft and creativity?

FP: No, it’s not just craft and creativity. Craft and creativity mean nothing if you don’t put it into some context. The same way that talent means nothing if you can’t manage it. Actually, talent could be your damning misfortune if you can’t manage it. You can have a super small amount of talent, but if you manage that well…

BW: And as a mentor, how do you balance motivating someone and keeping things realistic?

FP: That depends on what you mean by motivating. Students need feedback, but there needs to be encouragement too. When a student is almost too shy or fearful of what they would like to do, you have to encourage them and push them to get to that point. To really make them understand that what they do is great. Very often, it’s the ones who do really great things who are so intimidated by what they do. This is what separates the students who reach what they wanted or become part of what they wanted very, very quickly when they leave the course. These are the names that are around. They didn’t need motivation. They needed encouragement. And they needed to validate what they believed, no matter how naïve it was. Motivation lies in working with that and giving feedback and showing how that can exist.

BW: Are you looking equally at the loud and the quiet students?

FP: I think that, as a student, you need to be supported for exactly who you are.

BW: And can you always separate your personal taste?

FP: Well, I think you have to, but I don’t think you can separate it completely because you’re human. However, I think you should give an equal level of guidance and feedback and critical feedback on everything. If it had to be about what I like, then it would be extremely limited, because I don’t like many things.

BW: Are you known to be a harsh critic?

FP:I think I’m less harsh now. Sometimes I have to evaluate how harsh I can be, and we are in a time where harshness is actually a very difficult thing to put forward. I’m quite direct in my circumnavigating way of saying things, but I always say what I think. There are students who can handle a direct comment and there are those who need you to deliver it more gently. But from the students’ perspective I’m always harsh no matter what. It’s also a personal interpretation.

BW: There’s going to be a lot of people reading this, and it’s their dream to study at Central Saint Martins. What do you apply with? What do you submit?

FP: You submit a portfolio or a body of work that shows the evidence of how you think, work, imagine, your potential, and what your skills are.

BW: To be honest, I don’t even know what it means, “a portfolio.” It’s sketches, it’s fabric?

FP: It’s samples of work, isn’t it? We require four projects.

BW: Right.

FP: Four projects can be monumental, so we require extracts of four projects. In which you demonstrate how you research, where your idea came from, how you translate those ideas into your design, how you communicate your design. And that gives us evidence of the way you work, of how you inform yourself and what is your point of view in fashion. Then, if you get selected for an interview—we don’t interview everyone, this year we had about 1,000 applications—

BW: Is there an immediate red flag for you?

FP: No, because you can have an extremely unrefined portfolio with plenty of good things in it. It’s not about the perfect portfolio. That’s the common misunderstanding among students, even on the course. “My work was really beautifully delivered and the work of so and so wasn’t.” But that one had content. Yours had less content.

BW: It’s not bad to submit a lot of things?

FP: It’s about what you propose. Students who apply to the masters come from diverse backgrounds, experiences, or levels of study and so they might not show a level of work that is very sophisticated in terms of presentation or delivery. Potential is the key.

BW: So, you show potential and get the interview. How many get the interview?

FP: Quite a lot because I like to understand who is behind the work. Maybe a third of the applicants.

BW: The interview is still online?

FP: Yes, since Covid. But there is a positive aspect to this: it’s less intimidating. It’s intimidating coming in here, I think. Imagine traveling at five o’clock in the morning from Berlin. You come to London and wait for the whole day to be interviewed, because you’re interviewed at four o’clock. I mean, how nervous would you be by then?

BW: I would shit myself. So, when people come in, they’ve already had three mental breakdowns?

FP: It used to be like that. They would have to come here in the morning, they would put their portfolios on the tables, and then some portfolios would be selected, and some portfolios would not be selected. A lot of pressure.

BW: So now you kept it online.

FP: A short interview, it’s about 15 minutes. It’s the way you respond to some of our questions.

BW: About the work?

FP: About the work. Questions about fashion, their point of view. Students hate questions about fashion.

BW: Really?

FP: Yeah. I want to know what it is that they like. What do they respect? What do they find interesting?

BW: And they think everything is bad right now?

FP: Sometimes the answer is dismissive. Like, “I’m not interested in fashion.” But if you’re not interested in fashion, what are you interested in? Why do you want to come to the course? That’s a really difficult question. Generally you get a very generic or well-rehearsedanswer. My advice would be that if you want to come to a course like this today, you need to ask yourself: Do I really need fashion education? And: What kind of fashion education? That’s the first question you can ask yourself.

BW: Well, what do you think?

FP: The course costs a lot of money. 35,000 Pounds for an international student. Why do you want to pay that amount of money to come to a course like this? If you don’t have a clear answer, then it’s a waste of your time and money.

BW: What if someone says they want to come for the prestige of having gone to CSM?

FP: I would question what I mean by prestige andI would use those 35,000 Pounds and invest in myself or my brand. Yes, Central Saint Martins has a name that is recognized, but it doesn’t have the power to make you.

BW: I can only speak for myself and that Central Saint Martins got me into conversations, but it didn’t keep me in the room.

FP: Exactly.

BW: And what do you see with students now? Do they all want to do their own brand, or do they want to work at houses?

FP: They start by saying they want to do their own brands, then they learn that there might be other things they want to do. Within the two years, you find more career pathways and houses you can go to or you decide to do your own brand. We don’t necessarily show the students “these are all the jobs you can do” because our focus is on the student. By the time they finish, they have an awareness of who and where they are artistically whether they want to admit it or not. At that point, they still have to start making sense of all that. They need that buffer period. Unless they walk into employment opportunities or get spotted immediately, which happens.

BW: So, it does still happen. A student gets picked up for a job straight after graduation.

FP: Yes. But then there can be administration issues. Sometimes it takes a whole year, and by then the graduate takes another opportunity or wants to do something completely different. Sometimes head of designs or other employers may want you, but they don’t have the exact position to include you. But then when they eventually do, they may still call you back.

BW: “They.”

FP: HR, talent recruitment, or emerging talent recruitment—all sorts. We have a relationship with big groups, brands. It’s interesting to see what they pick up on, which is not necessarily what we pick up on. Then there are the design teams of the brands. Whether they have decision power or not depends on the brand or organization they are in, but they still have a power to say to us, “we’ve seen this interesting student, can you put us in contact?” and take it from there.

BW: Which brands do the students all want to work for, or are they all completely different?

FP: They are talking about Bottega, Loewe, Marni, Maison Margiela, Balenciaga.

BW: A tiny pool. Out of a tiny pool who could afford this education.

FP: That is something I wanted to touch on earlier. If you think you are the kind of person that belongs in this course, but you can’t afford it, then you should try no matter what. If you are really a talent we can include in this course, we will find a way to include you. That is not something we can do with everyone but it’s something we can do with some. The gates are open. We have students who apply who are given an offer to study here, and they withdraw, without even trying to get a sponsorship. Just enroll. You get three weeks before anyone follows up for money.

BW: After I gave my lecture here this morning, a girl came up to me and said, “I don’t even study here. I snuck in.”

FP: Exactly. Don’t be immediately intimidated! There are scholarships available. There are not enough, in my opinion, but they are there. An institution like ours is elitist by default, but by nature we love the idea that we can enable access to those students who always feel they should be included. Also consider the wild card. The genesis starts at McQueen. If we didn’t have that mindset then there would have never been a McQueen. He wouldn’t have been able to study here. The head of MA Fashion made sure he got in and found the money for him no matter what, and we’ve continued with that mindset. And that’s important. Otherwise, the course would be full of the same kind of people. No variety. No diversity.

BW: This just reminded me of something. I hope it won’t offend you. I had just started my journalism course and the MA show was two weeks away. So, I asked my professor how to enquire for tickets. He said, “Figure it out, no one will do that for you.” I took his “advice” and in the end I went with a fake ticket. Photocopied. Thinking back, I was a security threat. But I really wanted to go.

FP: I totally respect that because that’s what we used to do when we were students. Once a year, we got onto a bus and the school would take us to the shows in Paris and then we would be released with no invites, nothing. But we wanted to be at the shows. So, in whatever ridiculous way, we always made it. Trying to push in, pretending to be a model, pretending to work backstage, hiding behind somebody going in. The trick was that you had to wait for some sort of big name to arrive who created a commotion.

BW: Now it’s more difficult. Security everywhere. But I don’t regret going with my fake invite.

FP: I remember one year, there was this student outside the venue of our show who pretended they were my brother. Security kept coming backstage, saying, “your brother is here. Your brother is here.” I don’t have a brother. But I didn’t say that. I said “okay, where is my brother?” And I went and got them in. They actually teach in the BA course now.

Credits

- Text: BRENDA WEISCHER