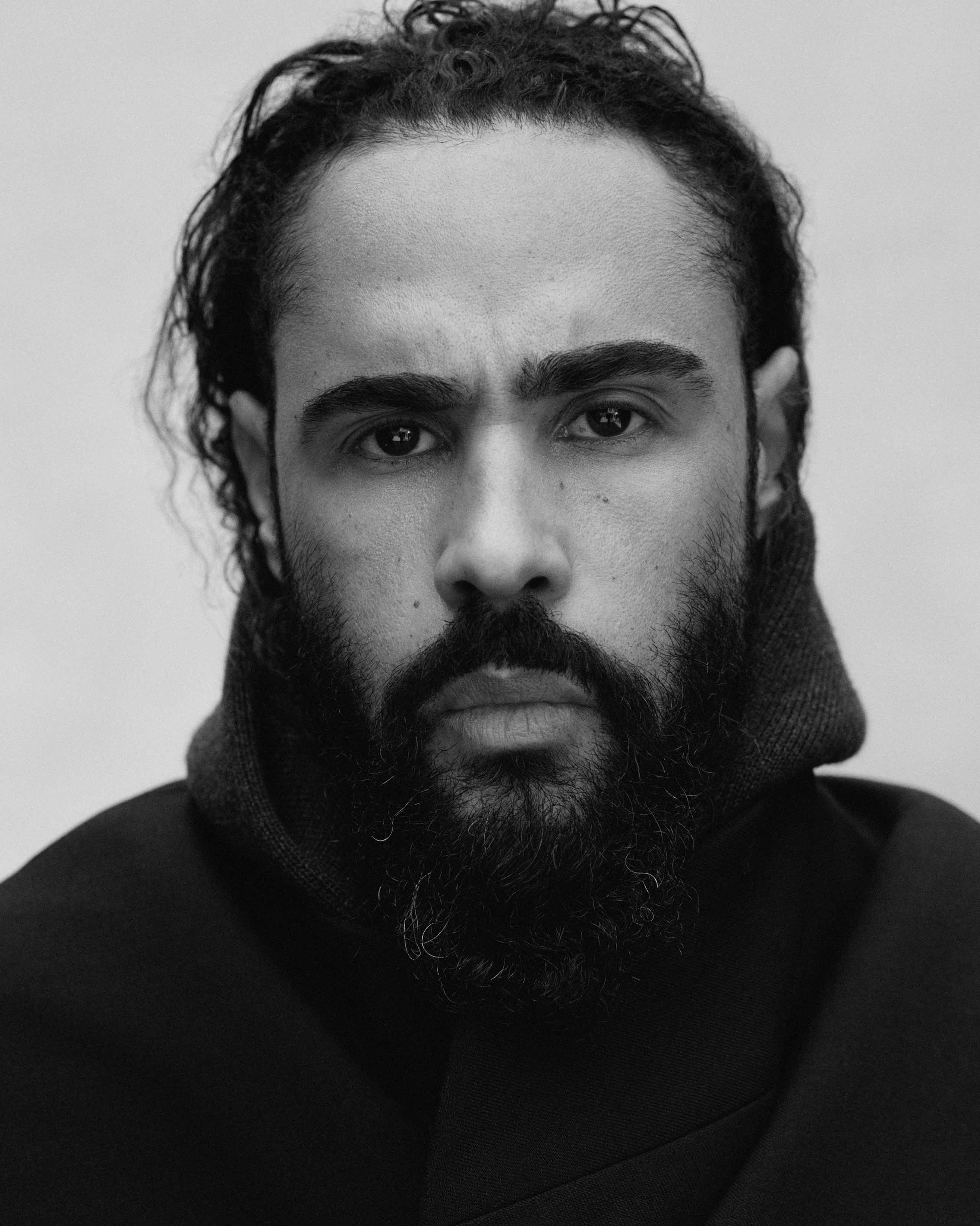

Brenda’s Business with JERRY LORENZO

|Brenda Weischer

During the weeks leading up to Jerry Lorenzo’s first runway show on April 19, 2023, there were more visual cues about his Fear of God brand in Los Angeles than for any other event taking place at the same time (allegedly Coachella also happened). Giant greige posters towered over the Santa Monica Freeway and Sunset Boulevard that were quiet if you compared their designs to the adjacent Netflix show promotions, but loud if you considered their size and location.

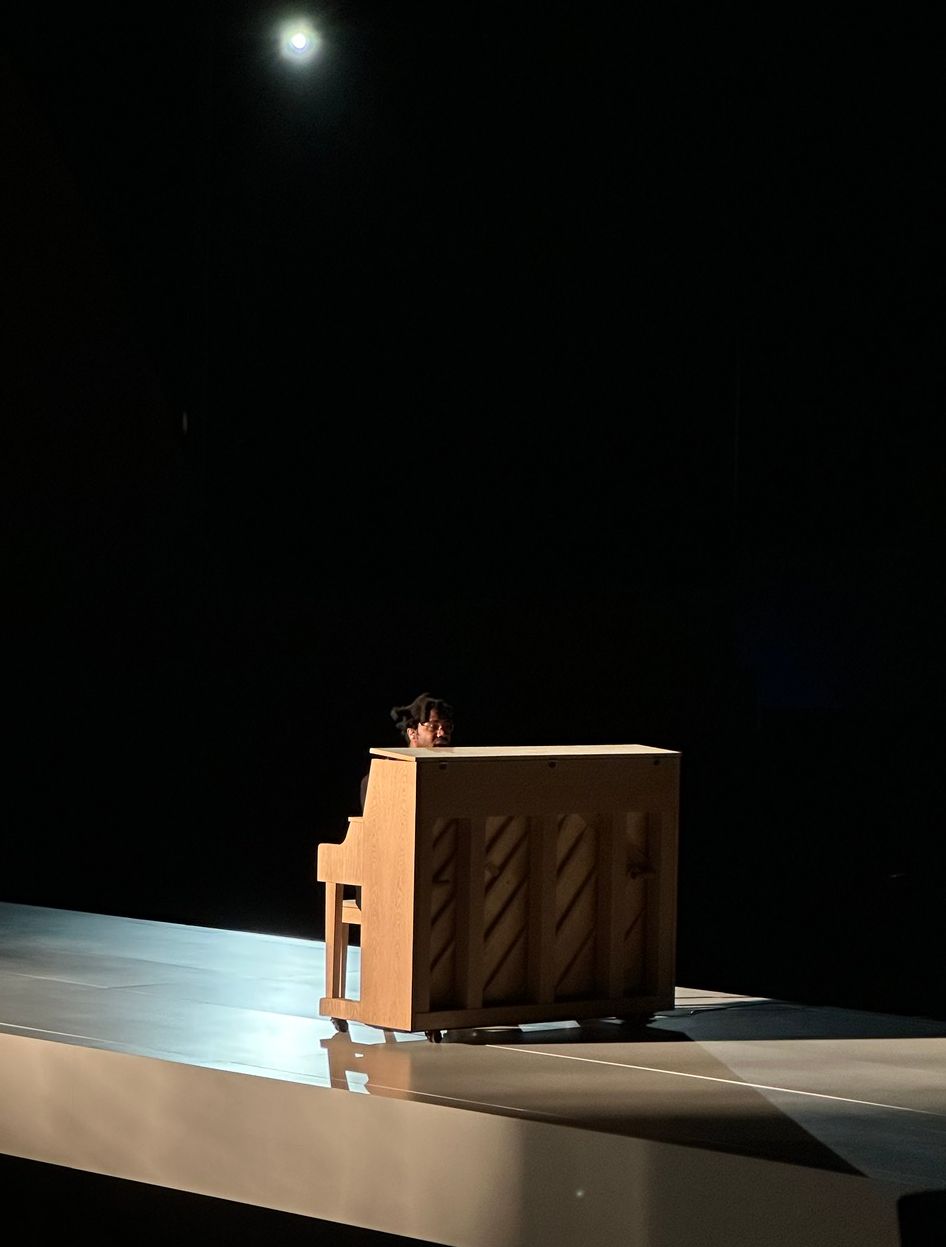

When it was announced that Lorenzo’s first Fear of God show would take place at the iconic Hollywood Bowl—an amphitheater that has hosted everyone from Frank Sinatra to The Supremes and The Rolling Stones—it was clear that the show’s sentiment was “go big or go home.” Jerry Lorenzo, the creative director who founded the brand a decade ago with no traditional fashion training, was in fact going big, close to home—he lives ten minutes from the venue. Putting on a spectacle, Lorenzo, who has never bent to the industry’s standards, assembled an absolute all-star team in the fashion world: Carlos Nazario styled Collection 8, Jawara Wauchope ran hair, Yadim Carranza directed makeup, Sampha opened the show with a live performance, Pusha T and DeAndre Hopkins made appearances, and the stage was graced by fashion superstars Anok Yai, Joan Smalls, Adut Akech, and Adesuwa Aighewi. By the time Alton Mason closed the show, everyone around me was on their feet. There were no show notes for press after, but the location, casting, sound, crowd, production, and creative direction didn’t need many words—if any at all.

I met Lorenzo two days later, and since I was sure he had heard enough compliments about his show, I decided to backtrack a little.

BRENDA WEISCHER: In 2013, you were a manager for an athlete and threw parties in LA for a living. Then you realized that there is a gap in the fashion market. I have this theory—or more a belief—that the best and longest-lasting brands start when someone creates a product for themselves and not for others. What exactly was that gap?

JERRY LORENZO: I think there’s always a gap in the market for anyone who wants to tell an authentic story. We’re attempting to tell a real human story, in an elegant and sophisticated way that’s easy to digest. I think that is the magic that makes room for your story to be heard.

BW: I read that Fear of God was entirely self-funded when you started. How much did you save from your previous work?

JL: I started Fear of God with like ten thousand dollars.

BW: What did you invest that in? How did you get into pattern cutting and sample making? How did you find people? Did you know anything?

JL: No, I honestly went downtown to the Garment District in LA and found people I knew. I knew people who knew people. But the patternmaker was the first patternmaker I ever met.

BW: You went with the first one you met?

JL: I was trying to make a long T-shirt. How to make that pattern probably took me six months to figure out. But I went through a lot of production development teams in Los Angeles. I don’t want to throw anyone under the bus, but ten years later, with further understanding of their job now, what they do is a hustle. And I didn’t know I was in that game because I was playing with such small units. Now I understand there’s a few people that work in that space and there are even more than a few that work in that space in an integral way.

BW: And then you had a physical product and had to find stockists?

JL: No, I immediately started with direct-to-consumer. I was throwing parties in LA so I kind of knew everyone. It was easy to get my clothes to certain people and it took off by word of mouth. My approach to seeding products was the same as to how I threw the parties. I didn’t want to call you and beg you to come to the party, I just wanted to throw the best one possible. My focus—whether it’s a fashion show, the parties I used to throw, or a product that we make—is on the product and letting the product make room for conversation.

BW: What I find special about Fear of God is that you completely ignored the fashion cycle from the beginning. Was that a thought-through decision or was it because you didn’t know you had to release every six months?

JL: I would say it was out of ignorance regarding the fashion cycle, but from a full understanding of how I shop. I don’t shop for Autumn/Winter, Spring/Summer. In the spring, I will get a coat when it’s cold. It doesn’t matter what season it is if I’m making something that someone wants.

BW: It will be good in three years too.

JL: Yeah. I didn’t really believe in having to deliver based on seasons. I felt more like having to deliver based on what people wanted. And to me, that transcends season. I knew that’s how I shopped and I was ignorant as to how products were bought, as well as about the lead times, and seasons, et cetera. When I had my first appointment with Barneys, they said, “Our buying season is in a few months, but we’ll take a look at your collection.”

BW: Do you still have to justify yourself to stockists? Do you have to explain that this is not how you work?

JL: Not at this point. If I had to, we would just work with someone else.

BW: You still being around and Barneys being out of business is kind of ironic, don’t you think?

JL: I think that there’s irony in the fact that when Shayne Oliver, Virgil [Abloh], and myself came into Barneys with HBA, Pyrex, and Fear Of God, we were kind of the first of a genre of designers. A genre that was hard to define. And I still won’t call it luxury street. It was just a new point of view that was hard to define. Unfortunately, I think Barneys thought that there were many more designers that were similar. But there’s a reason Shayne is Shayne. There’s a reason Virgil is Virgil, and there’s a reason why Fear of God is Fear of God. What we’re doing is so new and so disruptive that the industry can be confused.

BW: I listened to the BOF podcast with Tim Blanks where you talked about “transactional intent versus transformative intent.” Would you mind revisiting this thought? I think a lot of people get very lost in their transactional intentions.

JL: Our intent is not to transact with our customers. Our intent is to transform the way they feel about themselves through the product. If a blazer, a pair of trousers, or a pair of sweats makes you feel better when you walk out of the house, and it makes you become a better version of who you are, I have more faith in that than your purchase history with me.

BW: When I talk to people about Fear of God, they all bring up community. This dialogue, lasting over a decade, must be strong but it’s not visible to an outsider as there are no physical stores or shows. For a lot of brands, the only thing they have to lure people back in is the show. It’s the touching point every few months to remind people, “We’re here, and we’re here to sell product.” You don’t do any of that. How do you stay in touch? Where does the community meet?

JL: I think community is a product of who you are. We put our beliefs into our products, and that creates the community. We don’t intentionally gather our community to strengthen our relationship. It’s our core values that keep us together. It’s like this anniversary card I got my wife with two people on it. It explains that relationships don’t last based on us staring into each other’s eyes, but they last based on us sitting next to each other, staring at the future in the same way.

And I think the connection is much easier when you see things the same way. When you’re looking the same way at the future and not constantly trying to have community for the sake of having community. I would rather speak clearly when I have something to say. And hopefully, the message of the Hollywood Bowl is clearer than speaking for the sake of speaking two or three times a year through a collection. If my clothes aren’t ready and my pieces aren’t ready and my story is not ready, I’d rather be silent.

BW: Maybe you’re not looking around at what everyone is doing but most brands are screaming right now. Do you think a brand can exist for a long time today without having core values?

JL: I think a lot of brands exist without them. The reality is that the industry is based on transactions, and what’s happening is that a lot of brands understand trends and can build a successful company with what’s trending in the market. I think it requires a different approach to do something new, though. It requires telling a story that no one else is telling when no one else is speaking. It requires full authenticity. And that’s where my conviction is. I could never do this just for the sake of doing it and building a collection off a merchandise plan. That’s not where this is coming from. It’s coming from a different place.

BW: A different place… A lot of the people that you “came up with” have eventually ventured to Europe, to Paris. Was it ever on your mind to show there? Were you ever in talks with a house? Or was it always clear to you, “I’m in LA and I’m staying here”?

JL: My intent has always been to be here in Los Angeles. When Virgil took the job at Louis Vuitton, I felt like he carried a cross and gave us a point of view. Not that we needed validity from a certain space, but it did provide a different level of validity to what we have to say. And in some way, I feel like it freed me from having to go to Europe. I don’t desire being at a house where I’m there based on what they think is trending or what they think they want to say. Right now, I need to be in a position where I can say what I want to say without compromises.

One of the amazing things about Virgil was that he had so much joy in everything he did. Nike was like, “Hey, we want you to do these ten shoes,” and he said, “All right, I’m going to just have fun with them and do these ten shoes.” When I went to Nike, I was like, “I can’t. My gifts and talents are different. I have to make this basketball shoe. If it’s not good, it’s nothing.” And that doesn’t really work with going to a house where they want you to play with these pieces. It’s too limiting for my process of creating. It’s taken us two and a half years to finish Collection 8. I’m still learning, getting better as I go. That process can’t be rushed, it can’t be compromised. I know that if I’m at a house I don’t get to play Nina Simone and Tupac and Dinah Washington and a verse from Ye. Something would be compromised.

BW: When 99 percent of designers would say being at a house is the biggest goal, the biggest chance, your words for this are “limiting.”

JL: We’re attempting to earn the freedom to do what we want to do.

BW: And be your own house?

JL: Be our own house or our own brand—just be wherever we want to be at that time. Obviously, there’s a business strategy that makes it possible for money and resources to support that, but there’s also branding and other elements that help with that luxury. We want the luxury to take as much time as we want with these collections. The luxury to say what we want, when we want, and how we want to say it. And that’s what I’m fighting for. I’m not fighting to be at a luxury house and to be the next designer of the week. There’s an immediate clock against that. What we’re doing, I believe, is uncapped potential. And that’s where I find my peace.

BW: You don’t set a deadline for yourself?

JL: We set a loose deadline. We know we need to be in the market about every year and a half. And I understand the ebbs and flows of art, of who we’re speaking to, and when they need to hear from us. And so, we knew at the end of last year that it would be time in April. We pushed a little harder to meet this show deadline than usual and it was a good exercise. We’re usually just iterating until we get it to where we need it to go, and then release it digitally, or however else, to our community. But I think this physical day and the hard line in the sand made us exercise some muscles that we hadn’t exercised before, and that only made us stronger.

BW: Did you ever plan to do a show and then not do it? Or was this the first time ever?

JL: No, never. We did a presentation in Paris, but that was a collaboration with Zegna. We did it during women’s, and that was a little disruptive in and of itself. I think it was the first time they ever included women in their campaigns. But that felt a little dishonest. It felt like I was playing the game too much. Looking back, I would have preferred for it to have taken place in Italy where we made the collection.

To invite people to appreciate our pieces as art and not just wardrobe solutions, the craft needed to get to a certain place. I felt confident my product was at that level from a craft perspective, but I wanted to be at a place in terms of business, where we have the financial resources to express ourselves at a high level. In addition to that, I wanted to be really convinced of the story that I wanted to tell. And it wasn’t until April 19 that it was time to tell a story.

BW: Did you know immediately where you wanted to show?

JL: Yeah. To me, the Hollywood Bowl is the last iconic place in Los Angeles. It’s one of the best evenings. You could literally watch any band there and you’re just sitting under the stars. There’s something magical about it. It takes you to a different world. And I knew that if we were ever going to show, this would be it. And it’s authentic to who I am. I’ve seen everyone from Steely Dan, Stevie Nicks, and Nas to Wu-Tang, Diana Ross, and Michael McDonald. I’ve seen so many shows there and I love that venue.

BW: This show was not an announcement of “I am in the cycle now,” right? Did it create pressure to do a show every time you do a collection?

JL: The intention of this was to relieve the pressure. Not to say, “We can do this,” but to say, “We’ll do a show if we want to.” If we want to release a collection a different way, we’ll do it that way. But the intention is to never put ourselves in a place where our community assumes anything other than us wanting to put out the best product. There are no other assumptions that need to drive what we do.

Credits

- Text: Brenda Weischer

Related Content

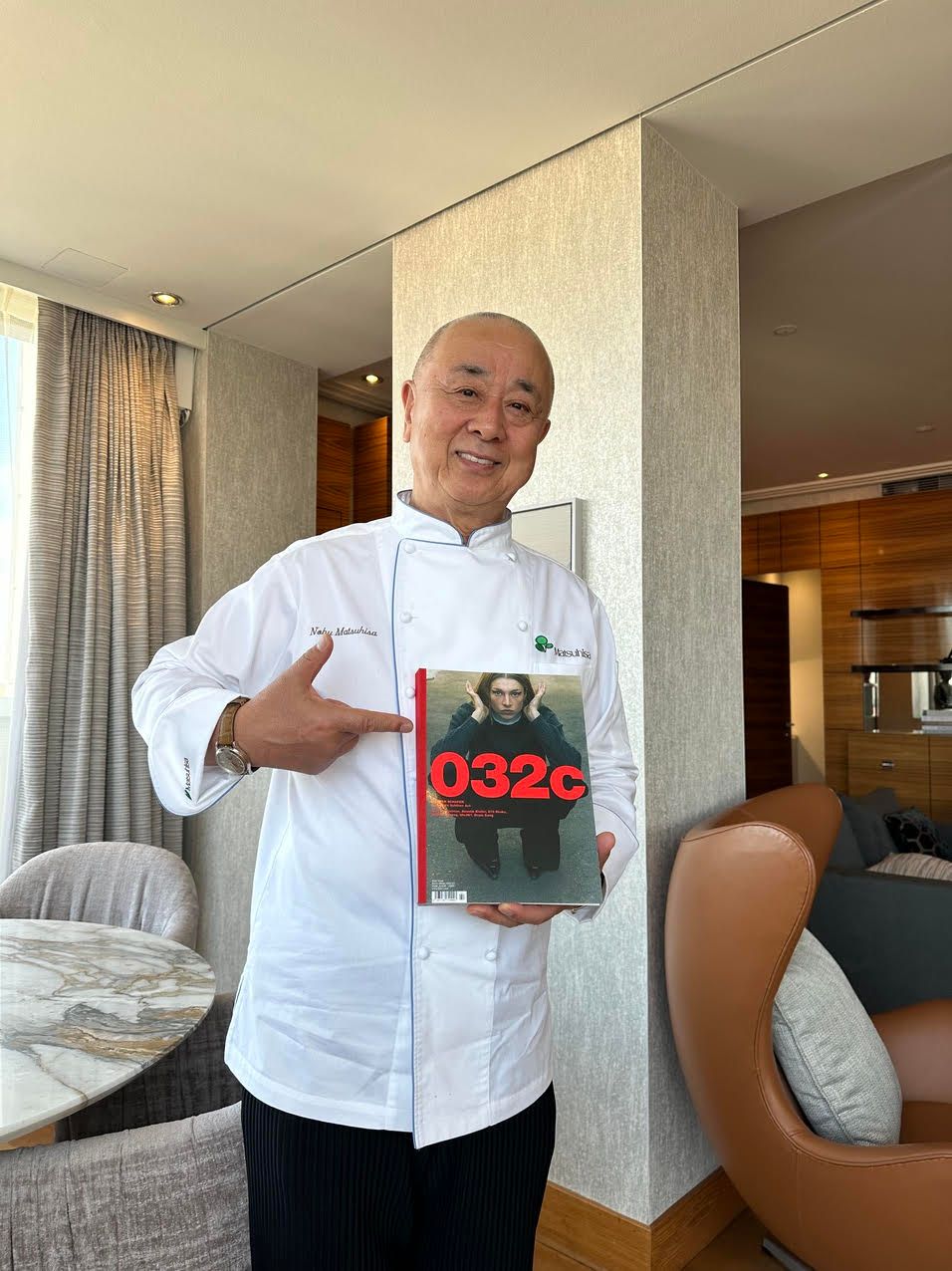

Brenda’s Business with NOBU

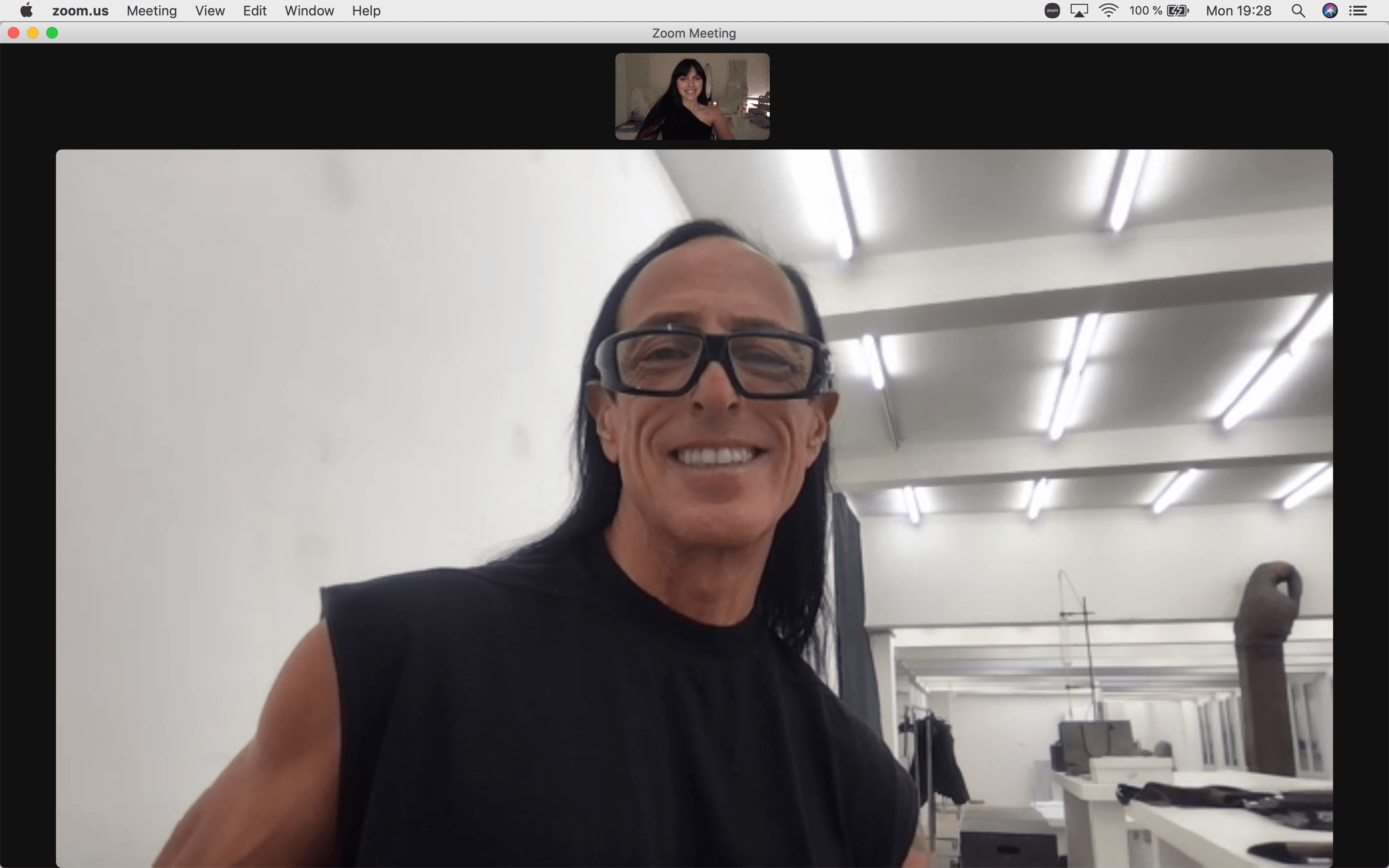

Brenda’s Business with RICK OWENS

Brenda’s Business with ISAMAYA FFRENCH

Brenda’s Business with PETER DO

Brenda’s Business with GSTAAD GUY

Brenda’s Business with MIA KHALIFA

Brenda’s Business with SHAYNE OLIVER

#SaveTheCraft: Alessandro Sartori and Jerry Lorenzo Co-Create with Fear of God exclusively for Ermenegildo Zegna