Keeping it Platonic: A Conversation with JEFF KOONS

|THOM BETTRIDGEBROOKE HOLMES

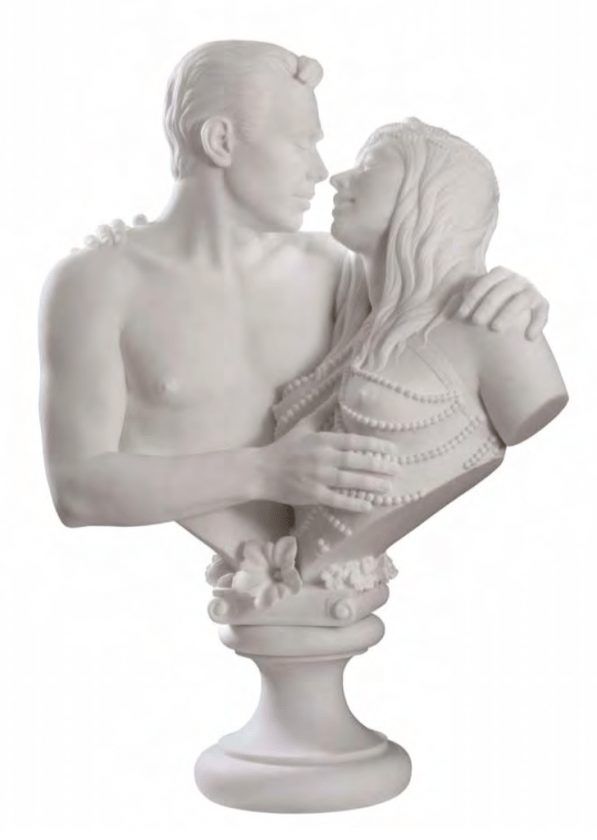

While sociologist Zygmunt Bauman famously argued that we are living in a time of “liquid modernity,” this description can lead to the dangerous assumption that there was something solid about the past, something immovable onto which we may anchor our nostalgia. Granted, the age of networks, drones, and fake news stirs within us a particular feeling of flux. But it is worth keeping in mind that the twin births of Western democracy and philosophy in ancient Athens were conjured up by a love for conflict and argument. In fact, classicist Brooke Holmes argues that throughout the Greek canon, chaos is vaunted as an essential component of existence. Her book Liquid Antiquity, created in collaboration with art collector Dakis Joannou’s DESTE Foundation, explores this fluidness of the ancient world. Its aim is to “de-petrify” the past, to melt the white marble of what we think to be classical and mobilize it in a manner that fluidly interacts with the questions of contemporary art. Such a project gels perfectly with the sensibilities of Joannou, who in 1988 teamed up with Jeffrey Deitch to create “Cultural Geometry,” an exhibition that collided together the then-trendy Neo-Geo painting movement with ancient Cypriot artifacts. Holmes’s book forms similar transhistorical wormholes, organized neatly into chapters on time, the body, and institutions. Her exploration sprawls into interviews with artists such as Urs Fischer, Matthew Barney, Kaari Upson, and Paul Chan. Here, she speaks with Jeff Koons about his unlikely affinity for Plato, a philosopher who scorned art and the carnal desires that define Koons’s work.

Brooke Holmes: Antiquity seems to have become increasingly powerful for you over the past ten years. What has drawn you to it?

Jeff Koons: What myth and art bring about is a sense of concreteness, a sense that we each have a self, that we are unique and have a place within culture and community. In my Antiquity series, which began in 2008, I wanted to show how our external cultural life emulates our interior life as well as our biology. The ways our genes and DNA are connected parallel the connectivity of our cultural life. I wanted to show that I have become a different person, that the viewer becomes a different person, after coming into contact with the work of an artist like Manet, and that Manet became different after encountering Goya, and Goya after Velázquez, and Velázquez after Ariadne. I’ve always loved the connectivity of art history. I believe art morphs in our genes and our DNA. You know, art, like life, is completely ethereal. It’s really just a chain of chemical reactions – a floodgate opens and one molecule affects another.

So the connection with ancient art is operating at a very deep level for you.

My interest in antiquity really comes from thinking about metaphysics, the im- mediate and the ethereal. I’m interested in what it means to be a human being, to have one foot in the past while at the same time walking in the present. Some people think history is confining, that it narrows us and keeps us from making gestures to the future, but I really believe the opposite. I think that history can change who we are and help us walk into the future more confidently.

You seem to be particularly inspired in the series by a cluster of mythological figures – Pan and Eros, satyrs – all figures that have a kind of animal or vital energy, an energy we associate with nature.

I think of Pan as a symbol of the eternal. There are two variations on the eternal: the biological, the life energy that leapfrogs onward in space and time, and the eternal as it exists in the realm of ideas – Platonism and pure form. I want my work to be in constant dialogue with these two realms.

One of the things that comes through in the Hulk Elvis series is this idea of repetition. Throughout your career you’ve worked in series and with reproducing images. How does the copy figure into the Antiquity series?

Many of the most wonderful antique works we wouldn’t even know about had it not been for Roman copies. If you think about a copy in Platonic terms, you have an idea of the chair, and then every other chair is just a version of that original chair. And when it comes to procreation, biological procreation happens in one way, but the inanimate world procreates through reflections. If I’m working with a copy, I’m doing it as a reference, because what I’m really interested in is the Platonic idea of the piece. If I’m working with a plaster cast and putting a gazing ball in front of it, for example, I want to refer to Silenus and the Infant Dionysus, or to the Mona Lisa. It’s not about the object per se, but about the original artist and the artists whom that person felt connected to.

Plato was famously against art, but he became important to the larger thinking about the classical tradition of beauty and form, and its aspiration to something higher. What is Platonism to you? Is it the idea of transcendence?

Platonism is about developing self-knowledge and experiencing transcendence. It’s about finding the freedom to walk out of that cave and achieve the highest level of consciousness possible while also being aware of a responsibility to share that information with your community and society. It’s a beautiful philosophy. Plato’s belief that the eternal exists through perfect forms and mathematics really offers answers while at the same time remaining completely ethereal. I enjoy Platonism because of the rigor, because of how Plato looked at the world and tried to make meaning out of it. Even though I look at the soul very differently, his ideas bring things into concreteness for me.

What is your thinking about the soul? It’s a term we don’t often throw around these days.

Like I said earlier, I think life is just a chain of chemical reactions. Our biology is the result of chemicals reacting with the external world to cause reactions, and in response to that, consciousness is nothing more than stored chemical reactions that create memories. I think there’s ongoing potential because the elements in the world continue to have chemical reactions, but I don’t believe in a sense of true self, or an eternal soul, or anything like that. I believe in the elements. I believe in physics, and in gravity and the elements and matter and dark matter, and all the other things that are in play.

Credits

- Text: THOM BETTRIDGE

- Interview: BROOKE HOLMES

- Images courtesy of: DESTE Foundation