“The Nakeds”: Exhibiting Nude Drawing in an Era of Digitized Sexuality

Culturally speaking, nakedness is already widely circulated. Terabytes of pornographic videos are stored on servers worldwide, and tons of magazines featuring thighs, breasts, and sex scenes are being recycled daily—oscillating between a variety of platforms. The image of the naked body is no longer a taboo, but rather a source of visual fatigue. Yet nakedness in art still remains relevant. Every artist still has a body, and it serves a surface of fears, desires, and society’s restriction. Drawing, the medium which stands as far from technology as possible, is still loved as an intimate and tangible subject. The curved and broken lines are not meant to add to the global over-saturation of nude, they are introspective attempts to resolve the riddle of possessing and desiring a body, or feeling detached from it. Naked drawings reflect the contemporary state of humanity—vulnerable and deformed figures floating in a void.

“It is a dream, a naked dream. There is blood-red sun in the sky. Men and women ride into town on motorbikes. A naked motorcycle gang. Around and around dirt main square. Upon it a circus tent is pitched. They park in a line, dismount and enter. Inside they take their seats on the rough wooden benches. The smell of animal, hot earth, popcorn and diesel”, writes David Austen, artist and co-curator of “The Nakeds,” in the beginning of his essay about the exhibition. It shows how personal, weird, and subconscious our experience of nakedness can be: both as thoughts of our own, and as a cultural concept.

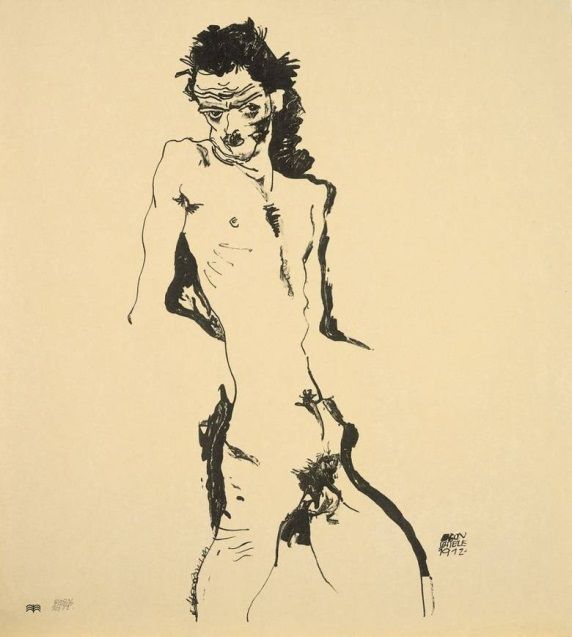

The idea of the exhibition emerged from Austen’s conversations with Gemma Blackshaw, an art historian and a specialist in modern Viennese art, about Egon Schiele, whose work was a crucial turning point in the representation of the naked body. The curators tried to trace Schiele’s influence in contemporary artists’ work, and discovered that, for most, Schiele is like a pop star of their teenage years. His influence is hard to overestimate, but slightly embarrassing to confess. The curatorial model was intuitive and anarchic: “The Nakeds” is a group show Schiele would be happy to be part of, if only he were alive.

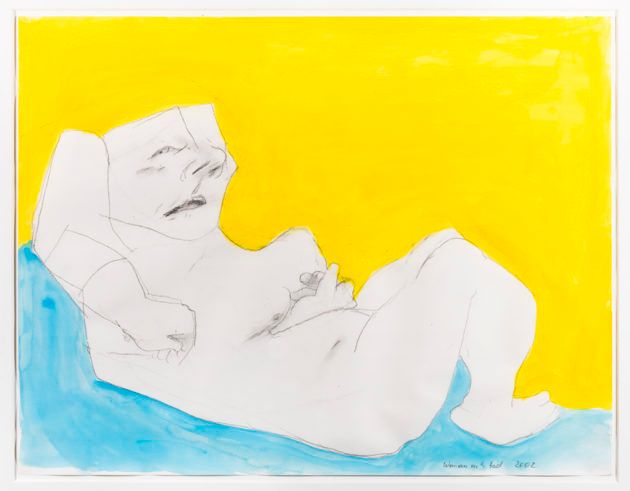

The visions of nakedness are incredibly varied—from George Kondo’s perfect Hollywood beauty with a monstrous face to Nicola Tyson’s ghosts to a matriarchal totem by Louise Bourgeois to lovemaking drawn by Tracy Emin’s shaky hand. They all expose a certain form of metaphorical nakeness: intimacy, society’s repression, a circle of shame and desire. The show challenges the distinctions between the erotic and the pornographic, trying, in a way, to bring the nakedness back to the territory of what is shocking and exciting.

032c spoke with David Austen and Gemma Blackshaw, and curators Kate Macfarlane and Mary Doyle about nakedness and the nude, the rejection of voyeurism, and the feminist approach to representing the body.

How did Egon Schiele’s work become the starting point of the show?

Gemma Blackshaw: When we think of Schiele, we think of him in the context of his mentor Gustav Klimt, in relation to Sigmund Freud working on his essay on sexuality and interpretation of dreams in Vienna at the same time. What interests me is that, around 1900, Vienna was Europe’s largest producer of pornography. There was a real industry in the city. We mostly think about Schiele’s work in terms of the erotic as opposed to the pornographic, keeping the distinction between the two. I was interested in challenging those distinctions, returning to what was so smoking about his work. Schiele was really concerned with testing these limits, challenging what was and wasn’t culturally acceptable and legal.

Do you look at the show as exposing the changing trend for how the body is represented, or it is more about the artists’ personal reflections on body?

Mary Doyle: There does seem to be an interest in representation of the body currently. Perhaps, in this fast-paced technological world, there is a need to reflect back on ourselves. Drawing by association is a personal and clandestine activity, so it has long provided artists a freedom to express the physical and mental terrain of the body and sexuality. Our exhibition focuses on the idea of the naked, the body exposed and isolated, as opposed to the nude. As we put this exhibition together, several other exhibitions around the theme of the body emerged, and of course it runs concurrently with “Egon Schiele: The Radical Nude” at the Courtauld Gallery.

Putting together this show you wanted to reject the voyeuristic gaze. Why?

Kate Macfarlane: Historically, the nude in art is associated with the controlling voyeuristic male gaze. We endeavoured to select works that said something about internal experiences rather than images that conform to conventions of beauty.

How do you think the approach to nudes has changed in the current informational environment, when we are constantly exposed to pornography and nakedness?

David Austen: Yes, the body is more exposed in the media and in online pornography. Any dummy knows that placing magazines beyond reach, or a glimpse of a white thigh is going to be far more mysterious and enticing. The pneumatic pornography of today is deadly boring and controlling. It’s reminiscent of the black-market, but government sanctioned, vice in Orwell’s 1984. This show is about the exposure of the body and soul. It is the body as a naked vessel alone in the void. It sets out how drawing can be a terrain where intimacy can be shared. Drawing has a speed that consequently stops time. A petit breath.

Could you expand a bit on the feminist element of the show: woman artists challenging a historically male and heterosexual perspective the female body?

Gemma Blackshaw: As a feminist art historian of the modern period, I am interested in how modernists connected masculinity, as opposed to femininity, with creativity. For modernists, women can pose, but they certainly cannot paint. What impact has this paradigm had on woman artists working throughout the 20th century and up to the present day? In my research for “The Nakeds,” I conversed with Marlene Dumas, Tracey Emin, Chantal Joffe, Georgina Starr, and Nicola Tyson. How did they approach the gendered practice of painting? How did they choose to represent women. How did they contest the modernist paradigm? It is interesting that drawing was an important practice for all of these women, even those such as Joffe and Tyson, who we would more readily identify as painters. As Maria Lassnig, another artist in “The Nakeds,” once wrote: “The pen is the sister of the brush.”

Do you have a favorite work in this show? What’s special about it for you?

Gemma Blackshaw: I have specialized in the work of Egon Schiele for over a decade, and I have seen his drawings in a number of places—galleries, archives, a bank vault, and, most memorably, a downstairs loo. But the two drawings we have in “The Nakeds” depicting Schiele and his lover Wally are special because they are so unusual when placed in the wider context of this “anguished” artist’s oeuvre. The faint line, the soft pencil, the round face, and the full lip—these works are more tender than tortured, and this makes them an intriguing pair.

David Austen: I have thought about going into hiding with the Schieles. Joseph Beuys has been a large influence on my own work, and we have two wonderful drawings in the show. Enrico David specially made his frottage cadaver made of floor rubbings and brown wrapping paper. It’s bent and pinned to the wall, and feels like a fragile creature scurrying across it. Its creation for “The Nakeds” makes it special for me.