ATTILA RICHARD LUKACS: Polaroids

In today's media landscape, a book review is often a slap on the back. A handshake among colleagues that says, “well done.” But we have never been afraid to offer critique when critique is due. In our print section Berlin Reviews, we've always tried to take the propositions of a book seriously and push them to their extremes.

Archive Berlin Review from our issue #22.

“THE POLAROIDS REALLY GOT SERIOUS WHEN I MOVED TO BERLIN IN 1986, BUT MY FOCUS HAD SHIFTED ALMOST 100% TO CARAVAGGIO ...

I PHOTOGRAPHED MODELS IN IDENTICAL POSES. THE DEGAS POSES ARE ALL NUDES, AND THE CARAVAGGIO WERE NUDE AND CLOTHED. IF THE CARAVAGGIO FIGURES WERE WEARING, LET’S SAY, A BLACK, BILLOWY-SLEEVED SHIRT – WELL, THOSE WERE VERY MUCH LIKE BOMBER JACKETS IN THE CUT, WHICH WAS A UNIFORM. SO IT WAS VERY EASY TO PUT A BOMBER JACKET INTO A CARAVAGGIO BLOUSON SHIRT.”

– Attila Richard Lukacz

Michael Morris – “I have a recurring dream where I’m a serial killer,” Canadian painter Attila Richard Lukacs revealed to the Village Voice a decade ago. At the time, he was also struggling with a nasty methamphetamine habit (duly documented in the 2004 film about him, Drawing Out The Demons): “I was doing meth 24/7 while constructing a large junk installation. Eventually I built myself inside it and couldn’t get out. I had to have pizza delivered through a gap in the boards.” Once, while caught between dream and reality, he was unable to determine whether he had actually murdered someone. “I didn’t know. It was like, they’re coming for me tomorrow, and I spent 20 minutes on the toilet trying to decide what to do with my life.” He kept repeating the same question: “Attila, what did you do with the body?”

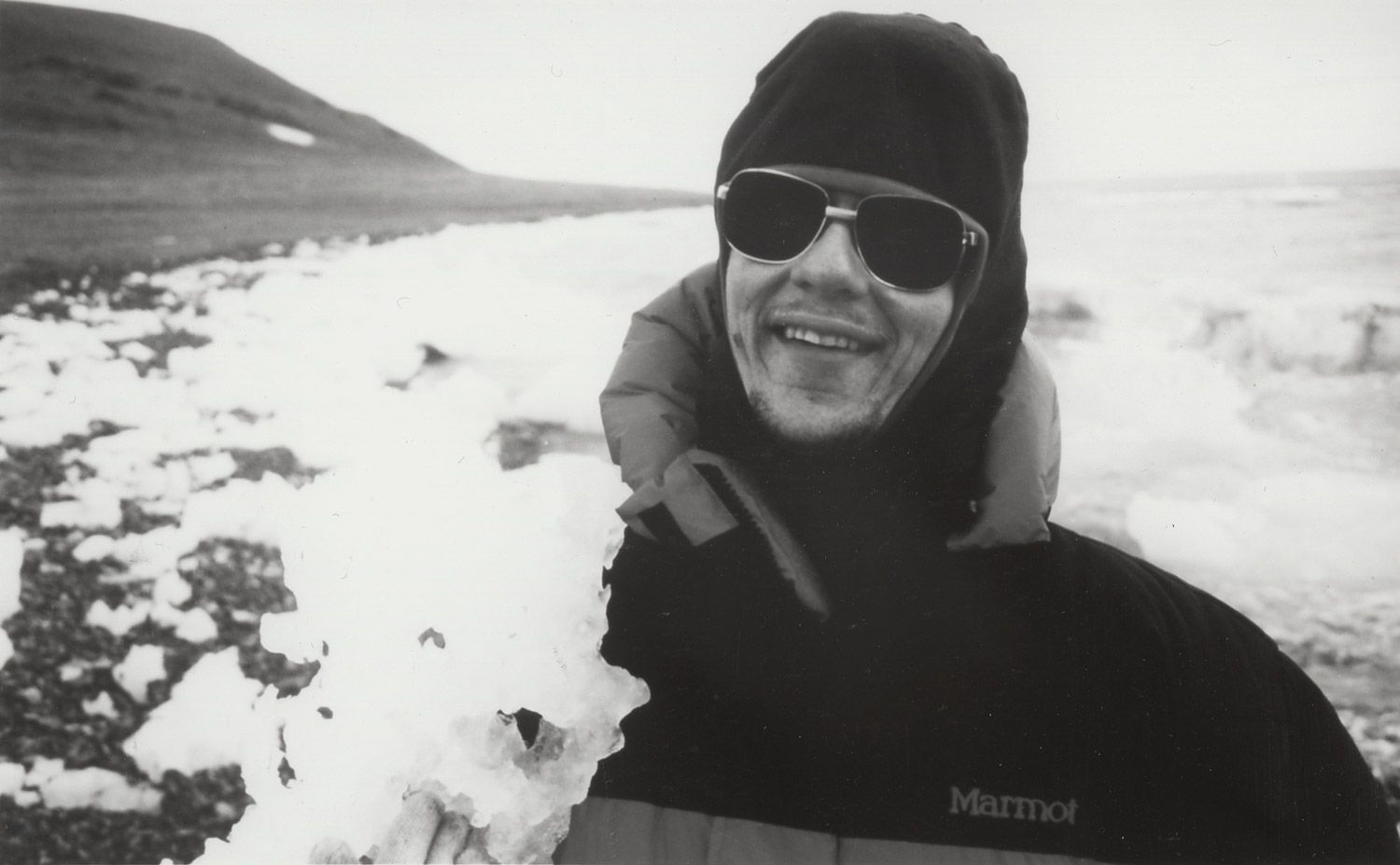

For the larger part of his career, which climaxed in the 1990s and was followed by a spiraling descent into polytoxicomania, critics focused on the carnage manifest in his large-scale paintings. On his canvases, muscular skinheads or military recruits, their proportions slightly skewed and their faces blurred, cavort in violently erotic reveries channeling Degas’ Young Spartans. In 1986, at the age of 24, Lukacs, the son of Hungarian immigrants to Canada, moved to Berlin, where his friend and fellow Canadian artist Michael Morris helped him to successfully apply for a residency at Künstlerhaus Bethanien. His was a Berlin at the very nadir – or peak, depending on your perspective – of the Cold War: a decade after Bowie’s Heroes, bunkered between the eternally monumental architectures of Schinkel and Speer, the cracks in the Wall already mapping out a land yet to form. It was the time of End Art, Die Tödliche Doris, Einstürzende Neubauten and a Weimaresque gay scene obsessed with archaic paraphernalia and iconographies: thanatoerotic Gestapo uniforms, combat boots, bomber jackets and the musky odor of jockstraps. German intellectuals and historians like Ernst Nolte and Jürgen Habermas were bare-knuckle fighting about the Teutonic concept of self, revisionist history, and the atrocities of Communism; Attila Richard Lukacs, meanwhile, got himself a Polaroid camera and became a serial killer. What started out as research for his paintings, in which he recreated impossible sculptural poses of classical male figures by assembling them from different photographs, soon took on a life of its own. It became an obsession for Lukacs. Hundreds and hundreds of Polaroids fluttered through his studio, fusing with paint smears and other flotsam. His paintings have provoked comparisons to the work of Francis Bacon – the notorious Arthur Kroker used descriptors like “explosion of schizophrenia,” “hysteria,” “torture,” “discipline” and “violence” for Lukacs’ work. The immense archive of Polaroids that Michael Morris has collected, curated into an exhibition and made into a book, allows for a dismantling glance behind that public image. We see intimate, private, loving situations. Lukacs met his models in gay hangouts like Oranienbar, or around Berlin’s many squats, and quite a few of them were also his lovers, or rent boys picked up around Bahnhof Zoo. His highly repetitious way of photographing creates instant series. Shot with token backdrops chosen for practicality rather than aesthetics, the effect makes the images all the more revealing by focusing on everyday imperfections.

Polaroids. Photographs by Attila Richard Lukacs, conceptualized and assembled by Michael Morris, Arsenal Pulp Press, Vancouver 2010 www.arsenalpulp.com

Attila Richard Lukacz is represented by Johnen Galerie Berlin.