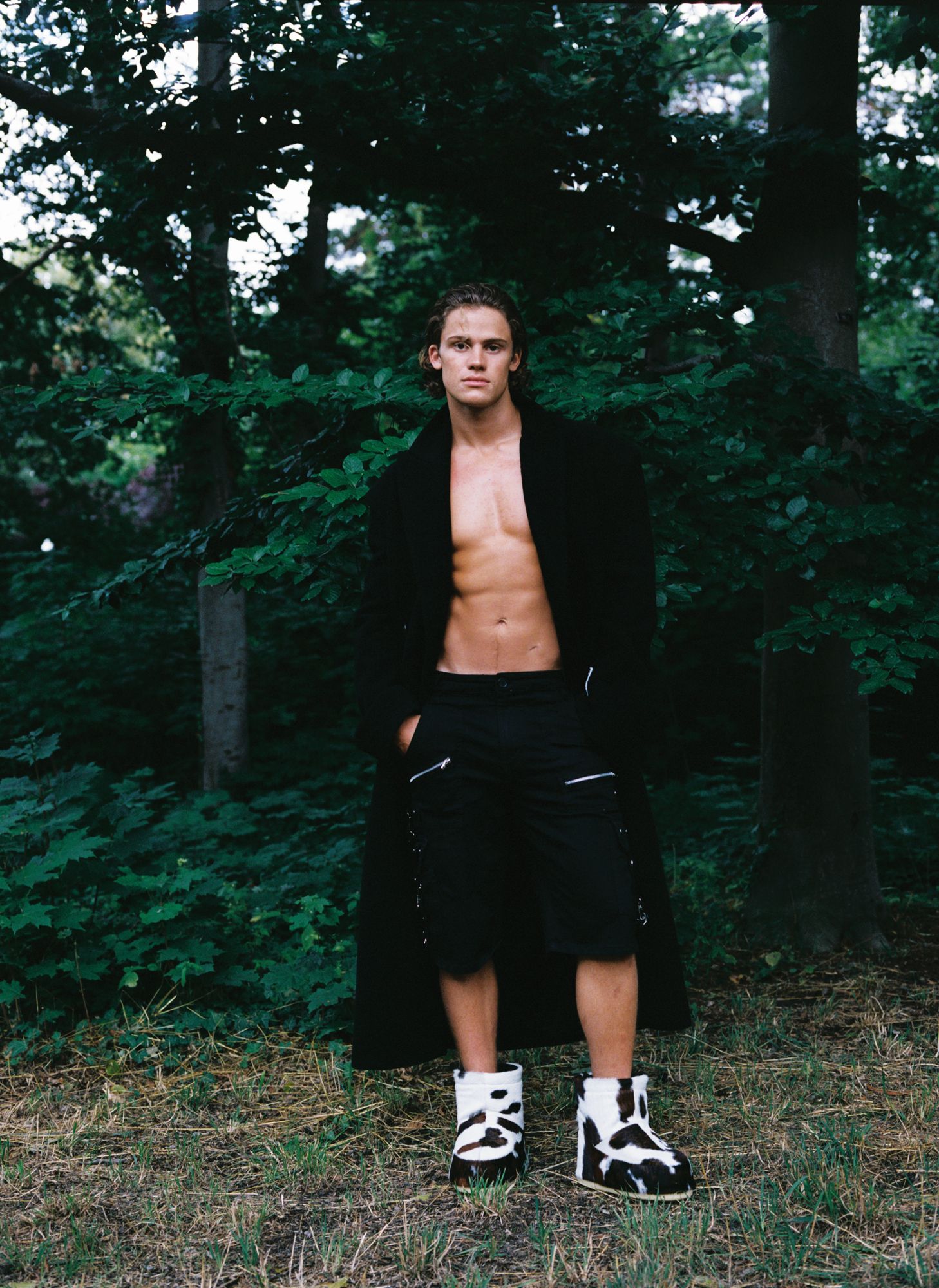

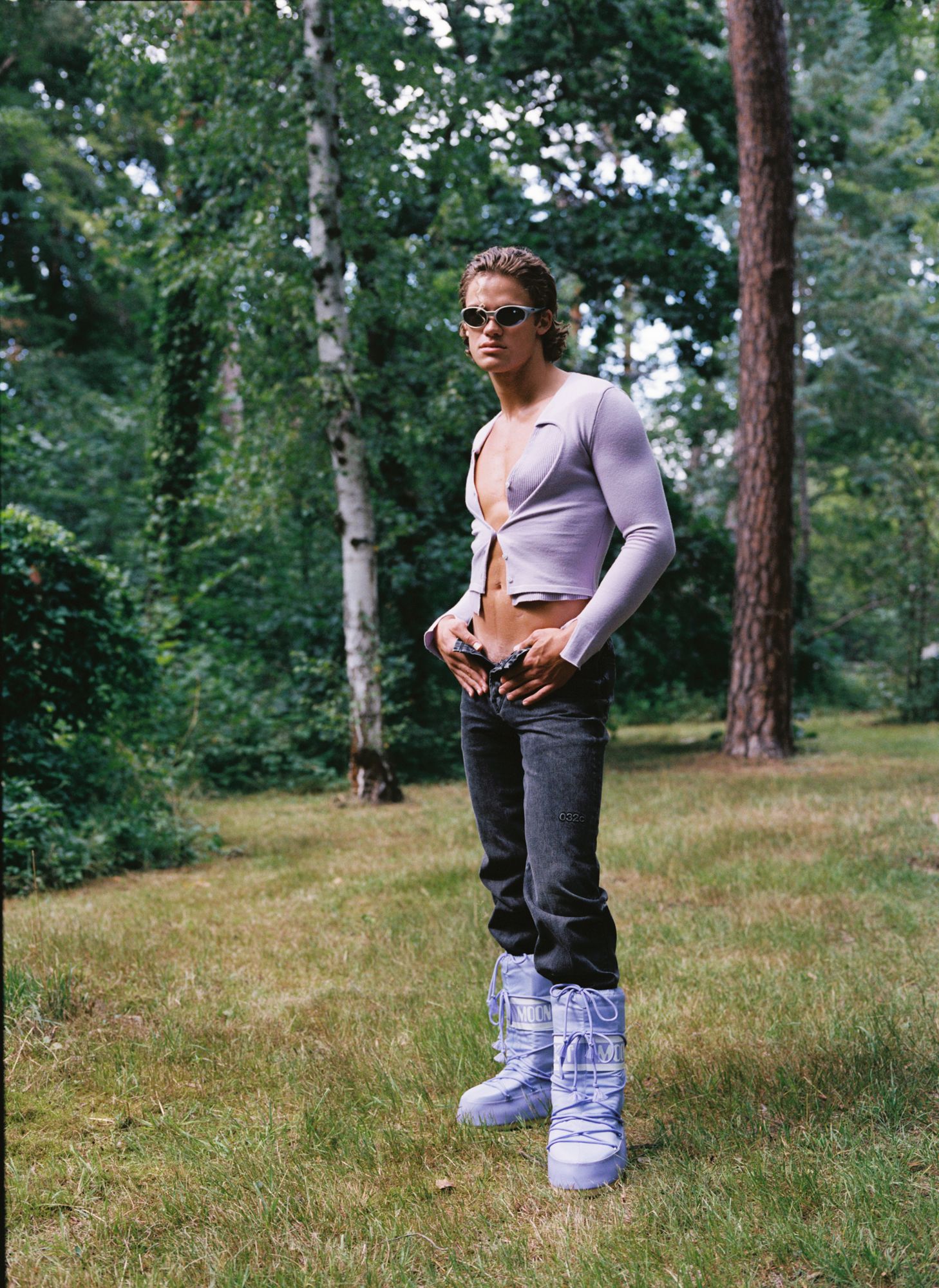

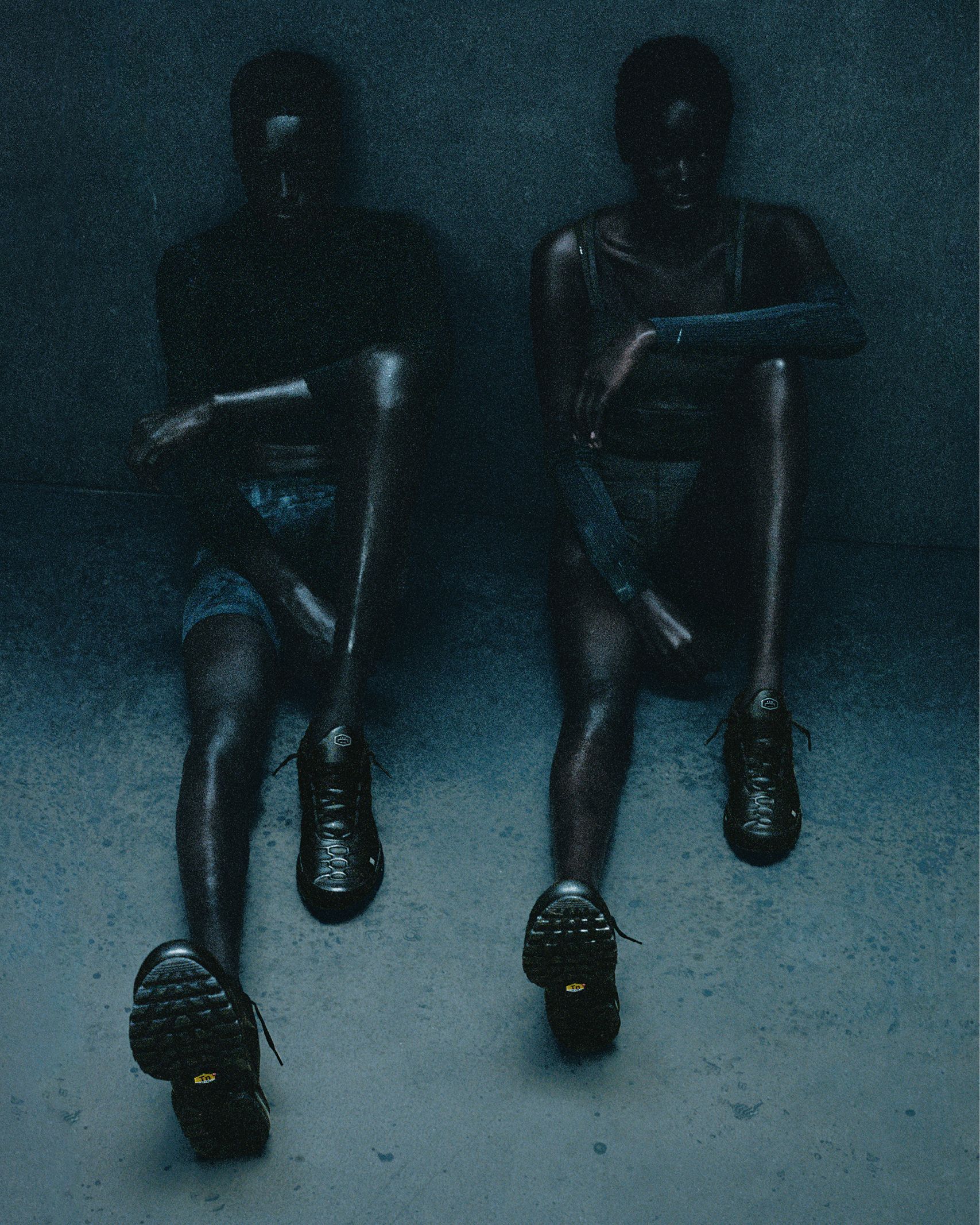

Après Ski with Lucas Braathen

When I spoke about the skiing in my hometown with Lucas Braathen, the Norwegian alpine ski racer who won the 2023 World Cup in slalom, he got very excited about Palisades Tahoe, a location I had surprisingly never heard of. “That’s because they changed the name,” he said, “the previous one was offensive.” As we spoke, it became clear to me that his excitement was not focused on the slope that had once hosted the Winter Olympics, rather it was because it was a station on his journey to skiing domination.

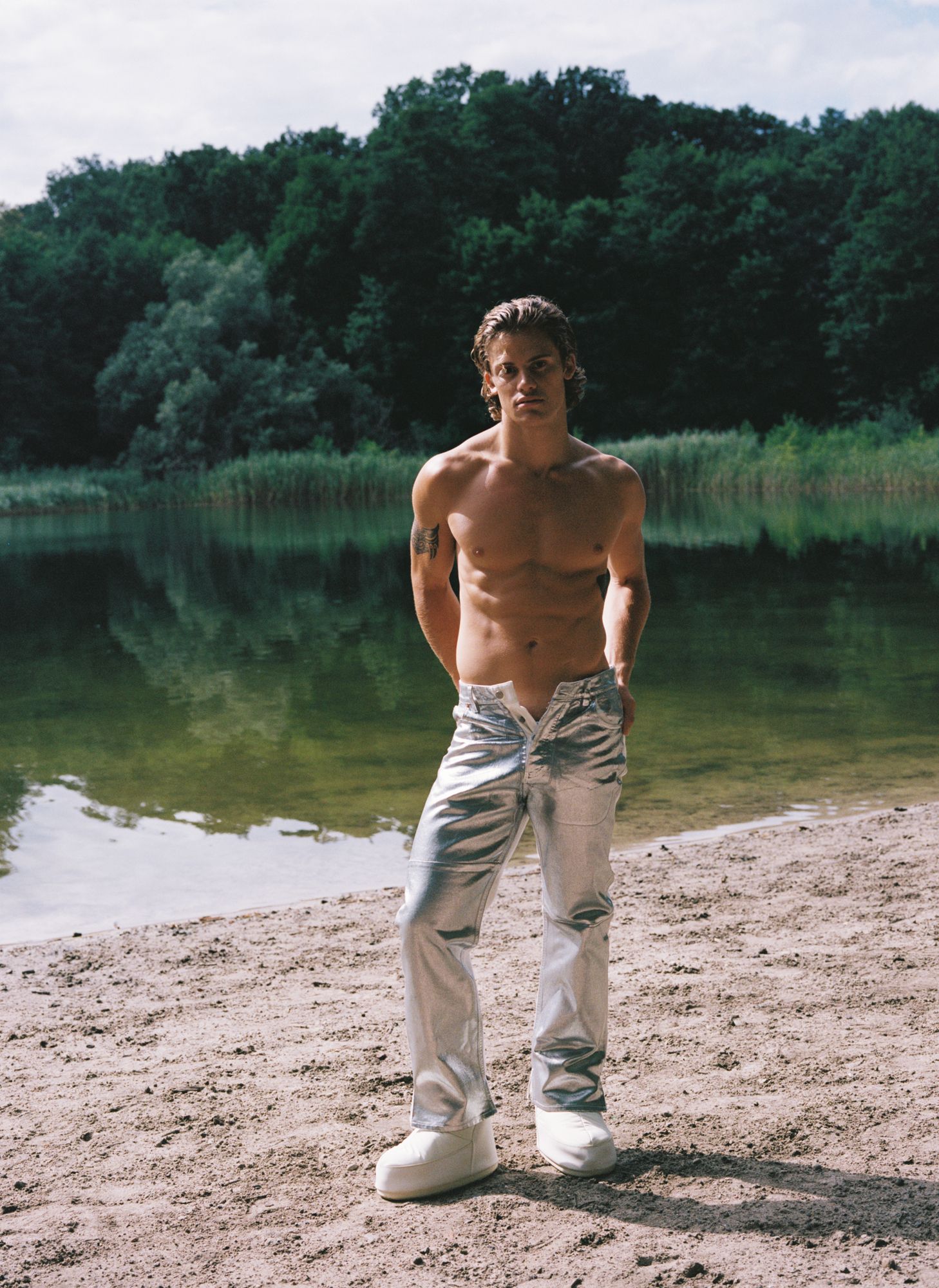

With five wins to his name, 12 podium appearances, and the World Cup trophy all taking place in but a few years, Braathen was at the top of his game when he shocked the world on October 27, 2023 and left the sport for good at the age of 23. This surprised me when I read about it on sports sites, but it made perfect sense after we spoke about skiing as showbusiness, about following your dreams—and of course, Moon Boots, which, as we will see, are synonymous with his success.

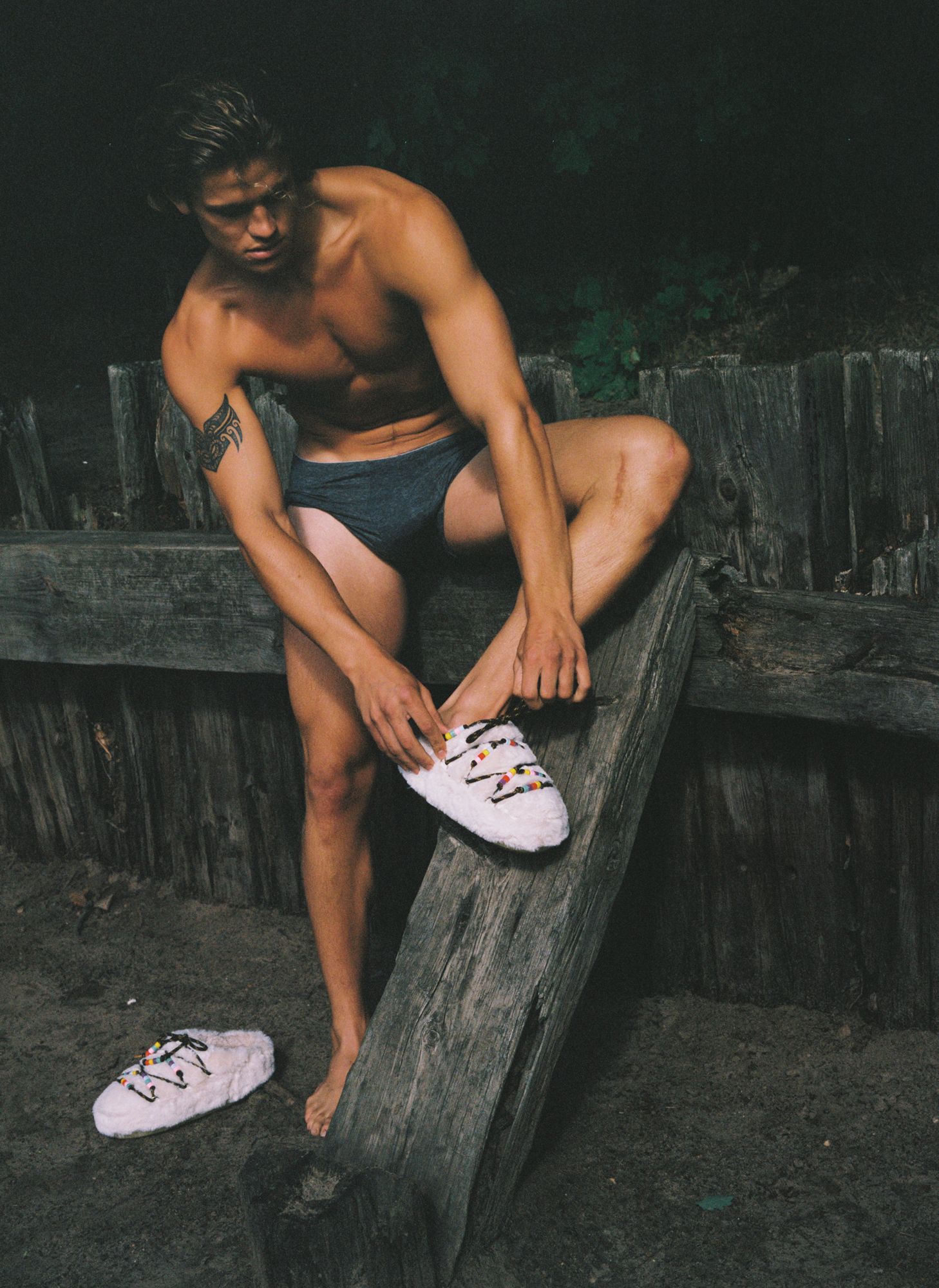

SHANE ANDERSON: Where I grew up, every kid wore Moon Boots after a day on the slopes. Was it the same for you?

LUCAS BRAATHEN: I very much grew up with my father putting Moon Boots on me as a kid. I’d be walking through villages and at European ski resorts with my Moon Boots that were half my height. They were a chance to make a statement and differentiate yourself in an environment where everyone dresses in the same conservative snowsuits.

When I started racing as a professional and won on an international level, I always made sure to jump up on the podium in my Moon Boots. They were a reminder of where I came from and a part of how I became the athlete winning races on a global stage. But the international press didn’t approve. There were articles, especially in Italy, questioning why I wore them and saying that I should act like a professional skier—which meant dressing in the super conservative snowsuits. They’d be like, “Who the hell does he think he is?” Articles like those made me want to push that prejudice to the breaking point, and when I won the overall World Cup in slalom this year, I made sure to wear a pair of pink Moon Boots.

SA: So, you started wearing them out of sentimentality and then out of defiance.

LB: I would say so. And when I’d read things like, “Men don’t wear Moon Boots, they’re too feminine,” I’d then be like, “I’m definitely going to own this—this is me.” I’m not going to change because their environment doesn’t allow it. They only gave me more of an incentive to differentiate myself in their conservative world dictating how you should look and speak.

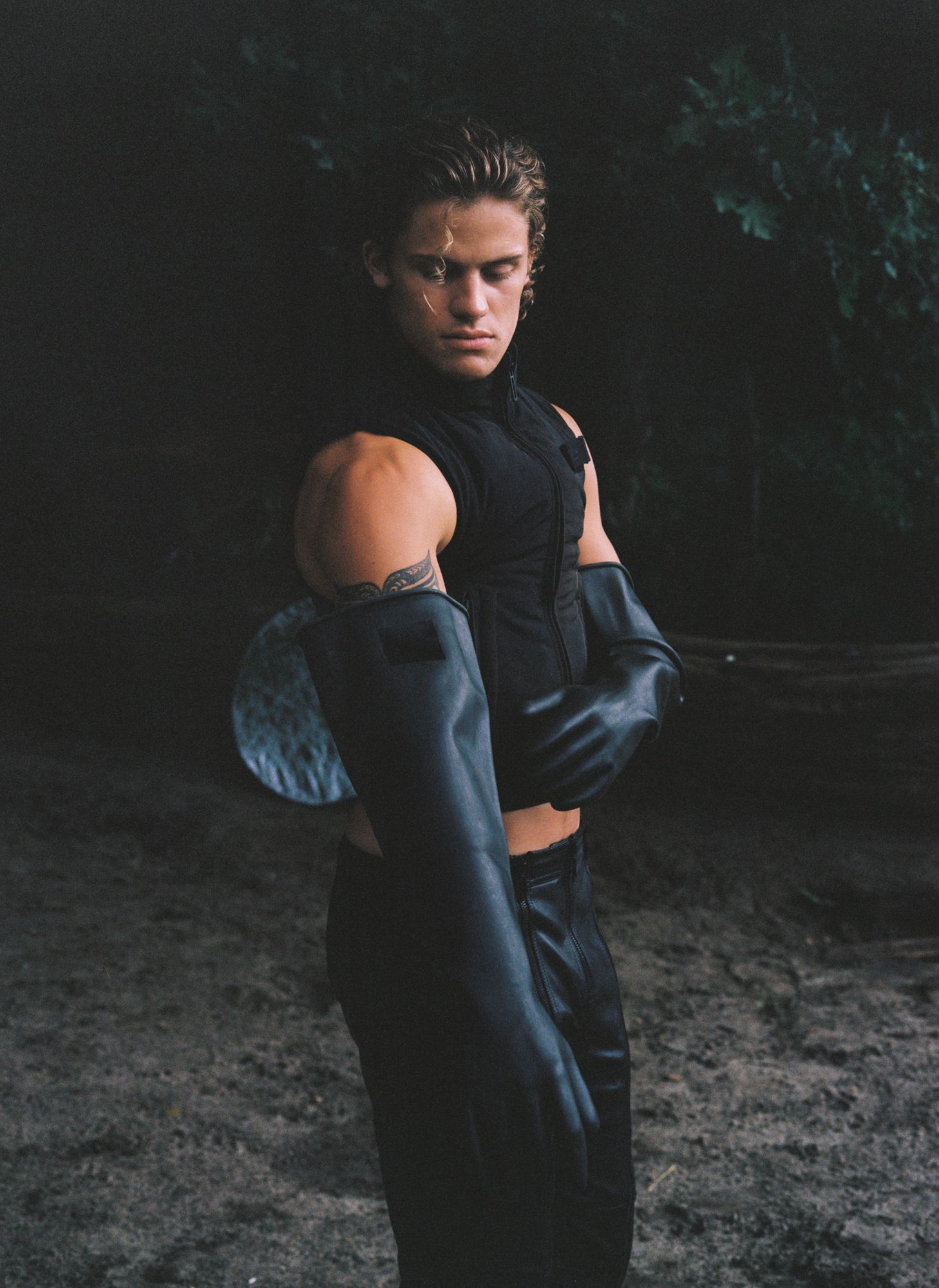

One of my goals as an athlete became challenging that very rigid environment and showing that it’s OK to be whoever you are—whether that be an extrovert or introvert or whatever. Just be you. And if you can do that, then you’re going to increase your possibilities to succeed, in part because you’re going to be happy. And Moon Boots felt like a perfect way to do that for me, since you’re very limited in what you can wear as part of a big skiing federation. On the podium, you’re basically stuck with the race suit condoms that have logos all over the place and that are not made in a very aesthetically appealing way. The only exceptions to the race suits are footwear and eyewear. That’s what I had to work with to visually represent and express my personality. So, when I was on TV and representing my country, I wore Moon Boots—there was no partnership, no money, and we never talked, but I was always wearing them on the podium—and vintage Oakleys—like those Dennis Rodman or Michael Jordan would wear.

SA: You suggested a desire to represent your personality with your clothes. What does Moon Boot and vintage Oakleys say about your personality?

LB: I’m a very curious person. Someone who is always looking for inspiration that doesn’t come from my sport. I try to learn as much as possible from people who have gained some success in very different professions or situations and then bring it into my niche, where I can then teach it to other people. I felt like that helped me gain an edge over my competition, who didn’t necessarily go outside of their own sport to learn new methods of thinking.

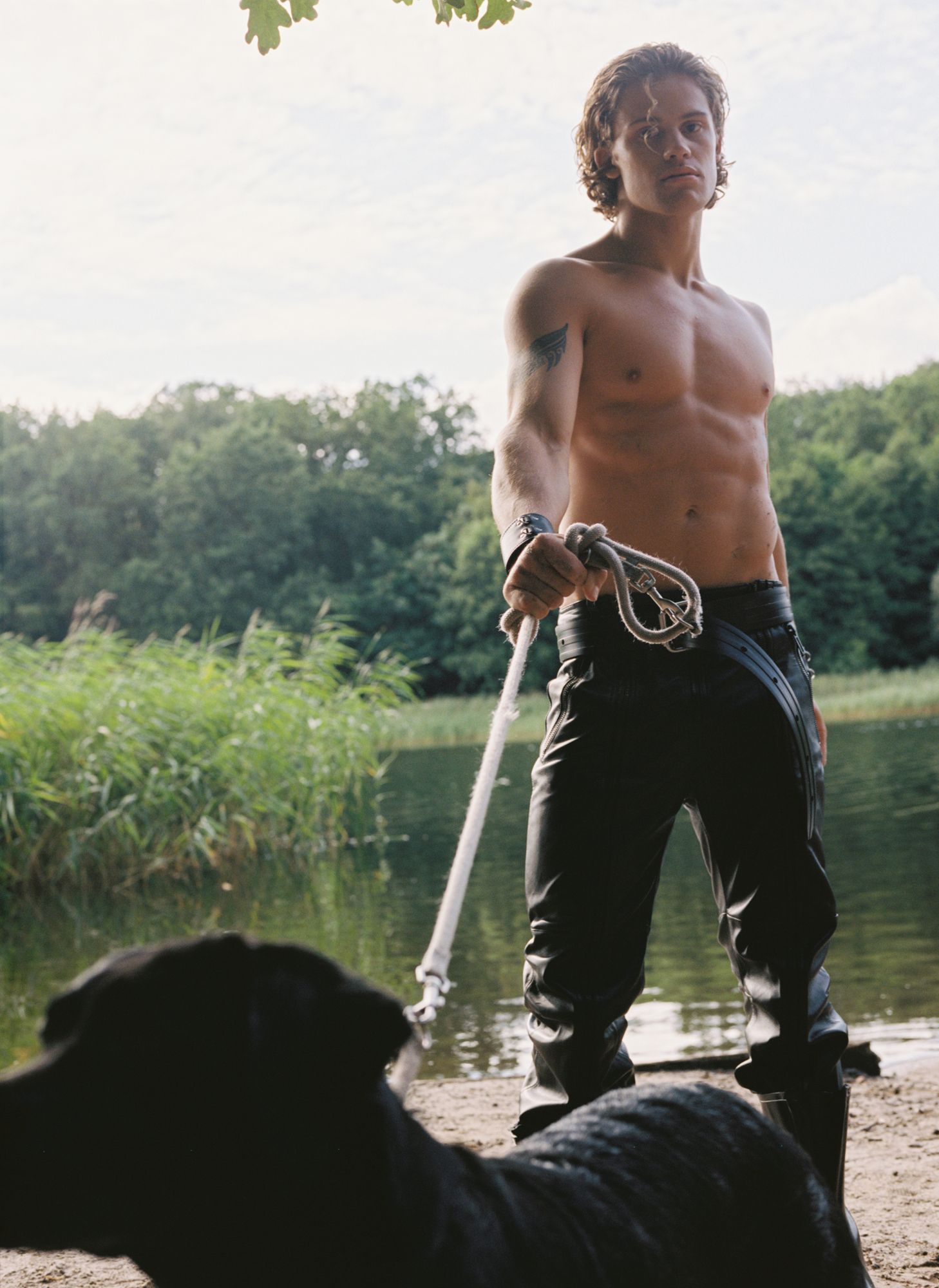

I would also say I’m a very expressive person. When I was growing up, I always knew I’d end up in a profession where I could express myself. As a kid, I was crazy about music and dancing. I would schedule a time in the afternoon every week where I’d put on a choreography in front of my family. I’ve always had this need to bring myself out of my comfort zone—and to do that in a way where I’m expressing myself and making myself vulnerable in front of a crowd—because I always felt an intense sense of satisfaction by overcoming that. And skiing became the best show business for me to express myself. That’s why I try to showcase who I am and be proud of that, hoping that it breaks the status quo and creates acceptance for difference—the sport of alpine skiing would definitely benefit from that.

SA: How is downhill skiing a showbusiness?

LB: First of all, it’s a visually pleasing sport. You’re going at over 100 km/h and then maybe jumping 80 meters into the air and that’s beautiful. It’s a crazy piece of entertainment. But what’s needed is to show the personalities underneath the helmets like the show Formula 1: Drive to Survive does. That’s what’s made Formula 1 so popular lately—in fact, it’s the fastest growing sport in terms of popularity—and that’s what I was trying to do. I wanted people to engage with skiing even if they’re not interested in the sport. They might only watch it because they might be fascinated by the personalities and the stories.

SA: But now you’ve walked away from skiing.

LB: I have, and there are a lot of reasons, but it really comes down to this: I had three goals in my career. The first was to be the best in the world at something. The second was to give something back to the community of sports , which I’ve done with my LUCI Foundation for kids. And the third goal was to transcend sports.

When I achieved the first two already by the age of 23, I decided to walk away and find what path I wanted to take to make a difference. It was really controversial to quit after being awarded the best skier in the world in the last race I was in, but I realized that if I wanted to achieve goal number three, then I’d have to leave the restrictive system that I was in. You know, one week after receiving the award at the World Cup Final, I was already back in the grind training. And I realized, that in order to keep skiing in this system, I’d have to put my third goal on hold. I asked myself whether I was willing to do that, and the answer was clear that I wasn’t. After all, the only way I’ve been able to achieve any success at all is by aiming for these goals.

SA: What’s next then?

LB: Right now, I’m still an ambassador for Oakley, Atomic, and Red Bull, but I’m transitioning from being an athlete to working in their creative departments. What’s in store for me long-term, though, is still very up in the air.

SA: If you could ski anywhere in the world, where would it be and what would the conditions be?

LB: If I was speaking about it from a sports perspective, I’d say a slope with very slick and compact ice. That’s where I thrive—on ice that hurts to your soul if you fall. But if you asked me about a “soul skiing day,” then the closest I’ve ever been to this was on the South Island in New Zealand, where I met a bunch of ski bums from all over the world, and they took me under their wing. They took me into this crazy backcountry, and we skied down to this turquoise lake amongst the craziest scenery ever.

And so, ideally, it would be like this. It would have snowed the night before. You’d wake up early, there’d be fresh powder, and you’d be hiking in the back country and not at a resort. You’re just wild in nature, no machines, nothing. Just you and the mountain.

Credits

- Text: SHANE ANDERSON

- Photography: JACQUELINE LANDVIK

- Fashion: RAS BARTRAM

- Talent: LUCAS BRAATHEN

- Production: MONIKA MARTINEZ

- Makeup: HYANGSOON LEE

- Hair: MASAYUKI YUASA

- Photography Assistant: DAVID MESA

Related Content

The rave as mosh pit: BAMBII’s INFINITY CLUB

Now Is/Was Forever: New collections from luxury sportswear pioneer JET SET

Angle of Attack: MONCLER Exploits the Advantage of Terrain

KNWLS Caters to Adrenaline Junkies in Their S/S-22 Campaign

Brenda’s Business with Rimowa’s EMELIE DE VITIS

Never Growing Up: GABRIEL MOSES and SAMUEL ROSS’ ACW_NIKE TN98

“Nepotism Is All I've Ever Wanted”: An Interview with BAKAR

INVENTING KIM KARDASHIAN: CHRISTOPHER KULENDRAN THOMAS