Learning a Vocabulary of Pragmatism: NIKIL SAVAL's Unconventional Path to Politics

|Andrew Pasquier

While creative ecosystems may be comfortably merging into what we’ve called The Big Flat Now, cultural industries and the convention-driven world of politics don’t necessary flow into one another so smoothly. Yet, as series of crises – from Covid-19 to climate change – confront younger generations, a new crop of activists on the Left are breaking though these false barriers, demanding political action from brands, publications, and arts organizations. Some, like NIKIL SAVAL, are even jumping into politics themselves.

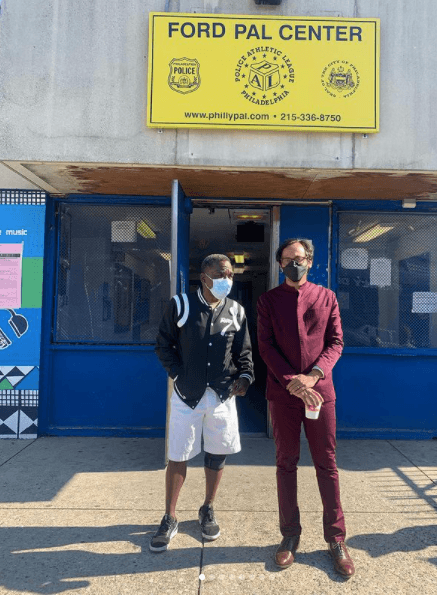

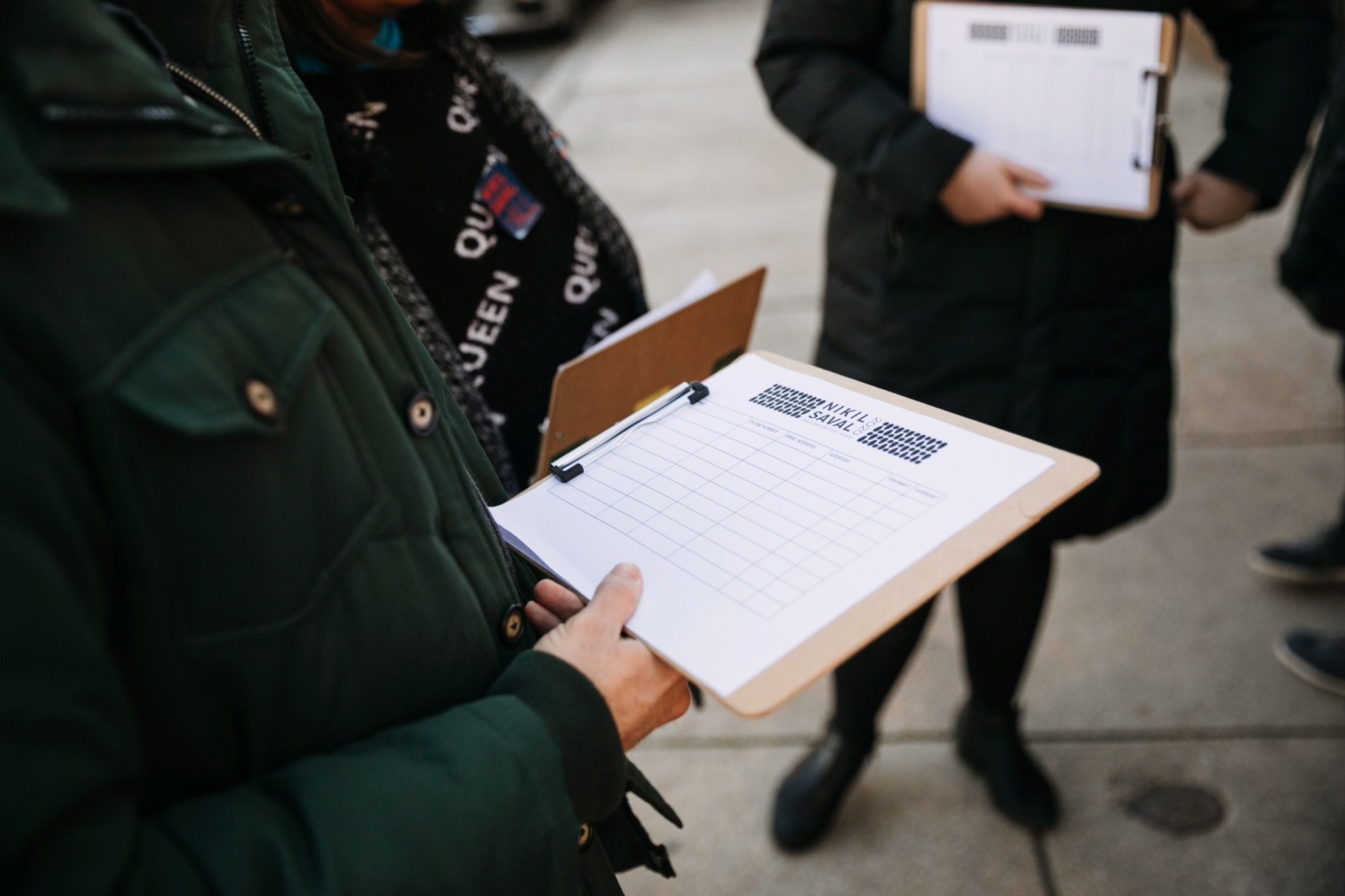

Saval has a resume that’s far from typical: before being elected to Pennsylvania’s State Senate last fall, he was the editor of literary and political magazine N+1 and author of Cubed, a design history of the corporate office. Pennsylvania’s sleepy capital Harrisburg is far from the downtown New York literary scene where Saval operated for much of the last decade, and he admits that to translate theory into praxis, he has needed to teach himself a new “vocabulary of pragmatism for politics.” Still, as he underlines, the political world has much to learn from the creative vocabularies of artists and designers, too, if big policy goals such as the Green New Deal are going to garner widespread support.

While Saval’s work is now rooted in Philadelphia, many of the issues he hopes to tackle apply to cities around the globe – and so do the solutions. While Berlin’s Mietendeckel or “rent freeze” law was recently overturned by Germany’s Constitutional Court, it inspired housing activists, including Saval, a continent away. In response to the ruling, a diverse coalition of artists and activists in Berlin gathered more than 300,000 signatures this month, forcing a referendum this September on expropriating major landlords in order to preserve housing affordability in the rapidly gentrifying German capital. With the Berlin debate in mind, Andrew Pasquier caught up with his own state senator from 032c’s Berlin office, discussing the environmental implications of each city’s housing stock and the need for more unconventional paths into politics.

Andrew Pasquier: In your new role on the Urban Affairs and Housing Committee, you’ve championed several bills seeking to extend a moratorium on evictions and foreclosures in Pennsylvania. These are crucial short-term policies in a crisis, but they don’t fix deeper issues that lead to housing precarity.

Nikil Saval: Right now we are focused on promoting housing stability and security through Covid relief measures, but we do have some bills in the works with longer-term implications—like sealing eviction records and banning criminal background checks in the housing market. Ultimately, we want to create a workforce development program for building green housing that is tailored to housing conditions locally.

In Philly, like in lots of places in the United States and across the world, you have an aging housing stock, and, at the same time, relatively high rates of homeownership. There is often no way for people who own homes—and certainly those who rent—to afford upkeep, weatherization, you name it. Many people are dealing with mounds of utility debt due to the pandemic, and in Philadelphia, it’s an issue that is disproportionately borne by people of color.

Two years ago Berlin passed an aggressive “rent freeze” law that retroactively lowered many people’s rent—bold public action that got lots of attention from housing advocates across Europe and America. Yet the housing stock in places like Philly is very different than the large apartment blocks of Berlin. What challenges do you see in trying to apply this type of sweeping government action onto the privatized logic of individual homeownership in America?

It’s a good question. Ultimately, we need to make it possible for individual homeowners to think, “I don’t have solar on my rooftop, but I want it.” It has to be easy for them to do it. The cool thing is we don’t actually need everyone to have energy on their rooftops—we can also connect people into a community grid. It’s even an idea Republicans are basically fine with, which is shocking! They generally have this visceral, almost atavistic rage against a lot of clean energy projects. But community microgrids? This one is okay.

“The Left, for a long time, has not seemed to be in charge of the future—the Right has claimed that territory.”

When you ran for office last year in the middle of the pandemic, people had very immediate concerns about their family’s health and economic situation. Yet your campaign made a big point of speaking about long-term, loftier political concepts like the Green New Deal. When you took these big leftist ideas to voters on the campaign trail, how do you make sure not to scare people?

I would say that it was it was easier than I expected, especially when it comes to energy and housing. These are infrastructures that affect your daily life. I mean, there’s a point at which politics becomes an abstraction—like when you’re talking about “millions of green jobs.” Joe Biden was using that kind of rhetoric, and certainly Bernie Sanders. This level of abstraction can start to escape people.

The Left, for a long time, has not seemed to be in charge of the future—the Right has claimed that territory. I think it’s starting to shift now a little bit, but back in the 1980s there was the Reaganite, Thatcherite revolution. The Left was tied to these old trade unions, while the other side offered a new neoliberal vision of the future.

But now there is this element of the Left becoming sexy again. Not literally, of course, but would you say that people are becoming more radical?

There’s a receptivity to new ideas altogether.

“When you’re a writer, you can retain some distance from a subject— you can retain skepticism, you can ironize your commitments, you can be pessimistic. But when you’re politically involved you actually have to make public commitments and believe in your arguments so you can pragmatically sell things.”

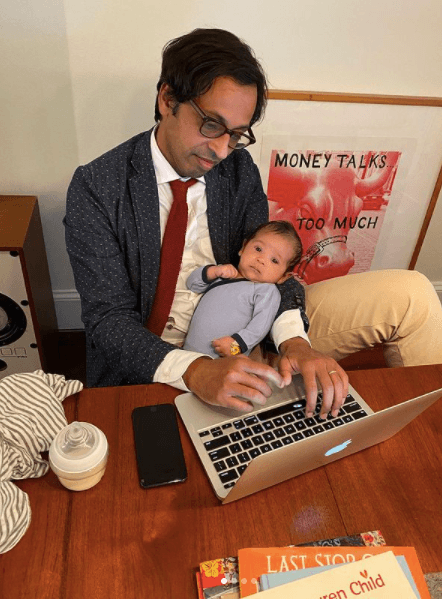

How do you relate that desire for new ideas and new people to your own entry to politics? Your path is atypical in American politics. You started in the academic, literary sphere before running for office. On the surface, they’re really different worlds.

There’s certainly a difference, but the difference is less stark than I expected. I actually find politics to be very rewarding intellectually. You can go into as much depth as needed on a certain problem, and then actually propose ideas or solutions rather than just analysis. It’s absorbing in a way that I couldn’t quite anticipate.

For about a decade you were a critic. A critic doesn’t usually propose solutions.

I got into design writing, principally, because I was curious about architecture in cities. I wrote my first book about the office. I was trying to write a labor history, but then you keep coming up against the spatial constraint, or nature, of that history. A good degree of modern work takes place in office districts, in office buildings, with office interiors that are a distinct spatial model from blue collar or manufacturing interiors. You can read design history—tested against the history of capitalism—as an effort to solve some fundamental problems about the nature of work, which then generates new problems out of those design solutions. I realized that there was this dialectical relationship between design and socio-economic life, labor, social problems, etc. That observation remains true, and subsequently led me to grow an interest in affordable housing and politics.

When you’re a writer, you can retain some distance from a subject. You can retain skepticism; you can ironize your commitments; you can be pessimistic. But when you’re politically involved you actually have to make public commitments and believe in your arguments so you can pragmatically sell things. I feel like I’ve had to develop both of those approaches.

I read the philosopher Richard Rorty a lot when I was younger. He has this sort of postmodernist, liberal ironist view that you just ultimately have two vocabularies: a vocabulary of pragmatism for politics, and a deeper, ingrained skepticism that is private to you. I find it hard to live without both. I’m sure there are other people for whom everything is good or everything is true across the board, but I’m not one of those people.

“I think a cultural shift is happening organically where a lot of arts institutions and media organizations now see their role in politics.”

Since you’re an expert on the corporate office, what do you think about the changes to work culture that we’ve seen over the past year during the pandemic? What could they mean for business districts like Center City Philadelphia or Midtown Manhattan? It’s a huge problem for municipal budgets that rely on commercial tax revenue, yet maybe this shift offers an opportunity to repurpose or reclaim urban space for new uses.

We were trending in this direction before the pandemic. There was already a shrinking proportion of office space per employee. We have all this empty commercial real estate that ultimately just needs to become housing. However, it’s an open question about whether these office buildings will actually become housing on terms that benefit most people. There already is a well-worn process by which commercial or industrial real estate is turned into residential usage: condos.

Most low-income people aren’t going to magically afford a luxury condo.

Exactly. Increasing the housing supply can depress rents overall, but it’s not fast enough—in the short term, it can actually increase rents. The weird thing about American cities in particular is that there are these “central business districts” that are just that. The very word “downtown” is American, fundamentally.

For something like the Green New Deal to work politically, it can’t remain a closed debate among policy experts. What kind of role do you see for people in the literary, art, or design worlds in transforming political ideas into a wider movement?

I feel like the Green New Deal needs to be approached as a collective cultural project—a little bit like in like the New Deal in the United States when there was a public labor force employing artists. People in the Depression didn’t have work, and honestly this past year with the pandemic a lot of people don’t have work either. Journalism, the literary arts, and other creative industries aren’t exactly thriving right now. To an extent, I think a cultural shift is happening organically where a lot of arts institutions and media organizations now see their role in politics. It’s a bit propagandistic but that’s part of it when people are really devoted to a collective project.

Credits

- Text: Andrew Pasquier