ALLEN JONES: Discovering A Muse At Madame Tussauds

|Phillip Pyle

The work of British artist Allen Jones has often caused incendiary debate—in fact, his work has even been stink bombed and doused with paint stripper by protestors. With a practice equally rooted in the circles of Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Minimalism that he flirted with while living at the Chelsea Hotel in the mid 60s, Jones engages with subjects of fetish, sexuality, gender, and the psyche through a distinctly Surrealist lens. Although part of the Royal College of Art’s famous 1961 “Young Contemporaries” show, it was in 1970 that Jones’ name gained permanence in the annals of art history. That year, Jones debuted three sculptures, Chair, Table, and Hatstand, which would become known as the “furniture” series. The fiberglass works depict women—modeled after Madame Tussauds waxes—clad in fetish wear, morphed into objects of pure utility and/or decoration. They would ignite Jones’ career, and the controversies surrounding him, eventually leading feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey to not so fondly declare Jones a master “of the language of basic fetishism” in a 1973 essay.

From early on, Jones was surprisingly plastic in his representations. In the 60s, works such as Man Woman (1963) pushed against traditional ideas of gender, inscribing masculinity and femininity as contingent, enmeshed entities. Jones’ interest in playing with the signifiers of gender can seem unfettered at times, and, at others, slightly perverse. Such is the case with Sweet Spot (2017), a multi-media work featuring a woman standing on a stool in front of a color field-esque canvas. Both the figure and the stool are painted, as if to deceptively blend in with the splotchy painting behind them. The attempt at naturalistic camouflage erodes at the woman’s feet, from which a heel protrudes seamlessly like a fashionable cyborg and whose toes are deliberately bulbous, even tumorous, in form.

Phillip Pyle spoke with Jones on the occasion of the artist’s current show “Jour de fête” at LEVY Galerie about Madame Tussauds, the invention of spandex, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, and the retrospective brilliance of the 60s.

PHILLIP PYLE: Very early on, you were clearly inspired by Surrealism and Futurism. And even once you formally strayed away from those movements, your work retained a psychoanalytic interest. How has your visual language shifted over time in relation to your more theoretical or art historical interests?

ALLEN JONES:If I look at the history of art, one of the things I notice is that artists have been interested in conveying “movement” since the dawn of time. Whether you’re looking at prehistoric cave drawings of antelope and bulls or Renaissance paintings of Bacchanalian scenes. In the Pop period, the main idea was that gestural abstraction had killed off representation. It’s absurd to think that one of the most ancient impulses, to record things we have seen, should no longer be possible because of Donald Judd’s “boxes.”

What became clear to me was that the subject matter was not the problem, it was the visual language being used that had run out of steam. The artists who taught me wanted to be compared to [Walter] Sickert whose work echoed Degas and so on, backwards into the Renaissance. Yet there were artists who wanted to create a new visual language appropriate to their time. [Edward] Kienholz, [George] Segal and Marisol come to mind, whose work I had just discovered when moving to New York in the mid–60s. I wanted to defy the notion prevalent in picture making that the canvas itself was what was important, as much as the image upon it.

By adding a narrow shelf to the bottom edge of the canvas, it self-evidently became an object, allowing me to paint as illusionistically as I liked upon it. After a while I realized that I wanted the figure I was painting to use the shelf to step into the real world—my world.

PP: There’s an element of deliberate disfiguration in Sweet Spot (2017). In these newer works, you appear to be both reimbuing the painterly gesture and, in a way, sublimating unconscious activity to the level of surface or consciousness.

AJ:You touch on an interesting thing for me. Initially I wasn’t interested in what the figure was doing. I just wanted a statuesque presence, like the caryatids in Athens. I then saw that they might still be construed as some kind of found object, a window mannequin, so I decided to make the sculpture appear to have a function, hence Table (1969) and Chair (1969). I wanted to dislocate the expectation of what art could be.

On returning to London, I decided to contact Madame Tussauds, in the center of the city, to find a commercial sculptor with whom I could work. They recommended Dick Beech who made figures in fiberglass. Working with him allowed me to remove the expressionist involvement of the artist’s hand. These sculptures were, for me, a totally new thing. I wanted viewers to confront the figures in the same way that they would confront someone they had never met before.

In the past 20 to 50 years I have become interested in combining painted sculptures into my pictures so that by moving them in relation to the canvas one can change the dynamic of the composition. In each case there is a “sweet spot.”

PP: The use of color is striking because it draws you into more intimate conversation with dominant art strands in the 1960s. In New York, you were surrounded by the influences of Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and a nascent Minimalism, and, in your use of color, I see the specter of Abstract Expressionism and even of German Expressionism. There’s almost a hyper-signifying use of color.

AJ: I was interested in the idea that interested Matisse in his maturity. The elements used to make a painting are line and color, and Matisse’s thing was: how do you make them have their own individual presence as well as illustrating or defining the other?

PP: You’ve mentioned before how lycra (or spandex) was growing in popularity when you were starting to make sculptures resembling the body in the 1960s, and how this ran parallel with figuration in contemporary art. The body was becoming more visible in fashion and in contemporary art.

AJ: With these new materials, limbs could be exposed yet covered. This created a freeing up of the figure.

PP: Your work is often interpreted in terms of sex being an innately physical or representational act. But that seems at odds with your psychoanalytic interest—psychoanalysis often sees sex in a very different light. The psychoanalyst Jamison Webster once said: “And this is what annoys people so much about psychoanalysts—as if we reduce everything to sex. But they fail to see that we don’t simply mean sex as like penetrative intercourse or something. We’re talking about what is repressed, disavowed, forgotten.” I’m wondering if you share this definition of sex, especially considering the fetish elements in your work?

AJ: In the last two years, I made my first video. It is of my Hatstand figure. There was a museum touring retrospective a few years ago, and the figure was away on exhibition. When it came back, it was funny to see the figure made 40 to 50 years before and realize she was still standing with her arms raised! After all this time I thought that maybe she should get a “break.” What if I made a video that let her relax and put her arms down. She remains a sculpture but, relating to your question, there was something that happened which I had not anticipated. She puts her arms down, she shifts her weight onto one leg, she tosses her head a bit, but what I didn’t expect was the figure looks as though she’s slightly pissed off with having to stand there. She seems to have a personality which isn’t about “look at me,” but about putting up with the fact that she is being looked at. The figure coming to life introduces a psychological aspect totally against the expectation of what this figure would be.

PP: This element of movement is complemented by this tendency to represent masculine and feminine energy enmeshing with each other—

AJ: Yes, particularly in my first lithographs in the mid–60s. The suite Concerning Marriage (1964) was influenced by the writings of Nietzsche. As a student, I had discovered his book Thus Spoke Zarathustra in a skip whilst cleaning windows during the holidays. I liked the idea of visualizing his concept that each of us needs to balance the male and female elements within us. I illustrated the idea with a sequence of dancing couples where you could not see where one figure began or the other ended—they become one, a metaphor for the feelings I had when making love.

PP: You’ve previously talked about how you aren’t bothered by your work being copied or reproduced. Today, issues of imitation or mimicry are incredibly popular in conversations around artistic production, especially because we now have access to other people’s work in a more instantaneous way. I’d be interested to know if you still view imitation as a form of flattery when it’s becoming even more ubiquitous?

AJ: When I was first in New York, I remember Lichtenstein was being taken to court because he had made a painting of a diagram deconstructing a Cézanne painting of Madame Cézanne. He got it from a book, and the writer had taken him to court. I remembered that the judgment was that one was an illustration in the book, and the other one was a painted canvas. They were different things. That you cannot patent an “idea” was very interesting to me. And if anything, I think it’s quite interesting how stuff morphs both in intention and motivation.

PP: Elements of imitation and reproduction, and ideas of virality were already embedded in the artistic production in the 50s and 60s. Did you have any sense that that era would come to have as big an impact as it has?

AJ: No, not really. I mean, I was 26 years old when I went to New York. If it had been 1910, I would have gone to Paris. But New York was the place to go. I had never seen any Pop Art in the flesh at that time, even newspaper color supplements brought home from America were seen as exotic objects signaling the explosion of media to come. In New York, there was a continuous display of visual possibilities being laid out month by month in galleries such as Sidney Janis and Leo Castelli. Thursday evenings, you went to these gallery openings, and it was an exciting, creative visual dialogue about formal issues of what art could be. And, you know, part of the buzz was the arrogance of youth—knowing that if something’s knocking you out that it, by definition, is going to be good.

Credits

- Text: Phillip Pyle

Related Content

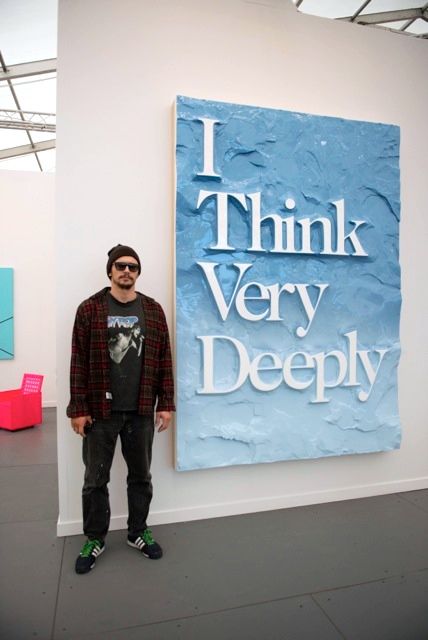

Actor JAMES FRANCO Reviews Frieze New York for 032c & Gets Photographed

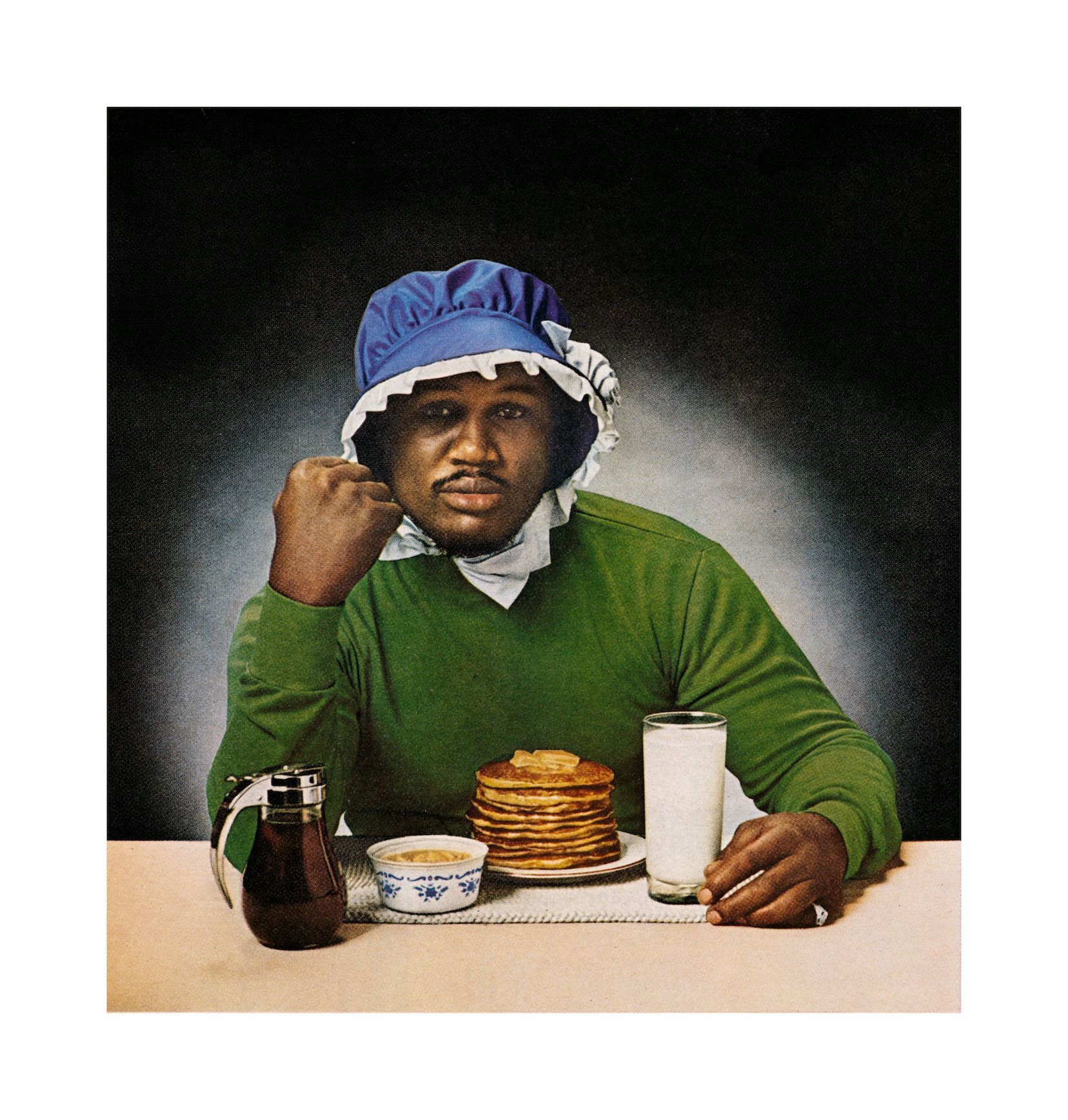

The Real Thing: Exhibiting the Art of the Bootleg

Sarah Lucas to Massimiliano Gioni: “I Didn’t Want a Boring Life”

The Real Thing: Exhibiting the Art of the Bootleg

Art World Resorts: A Remedy for Chronic Anxiety

Viscose: The World’s First Bagazine of Fashion Criticism

Art Critic JERRY SALTZ and 12 Supermodels Discuss the Selfie

“It’s Important to Be Visionary Rather Than Reactionary”: Artist Hank Willis Thomas’s Aesthetics of Mass Action