A Style Guide to Success by EZRA PETRONIO

|CASSIDY GEORGE

Coherence, consistency, and attention to detail – these are the keys to success in the fashion industry according to the art director, branding expert, and Self Service magazine co-founder, Ezra Petronio. Arguably, these principles of creative success run in Petronio’s blood. The native New Yorker is the son of an art director and the grandson of a typesetter (and head of the New York Typographical Union), both of whom worked in the magazine industry.

Following in the footsteps of his grandfather, Petronio studied typesetting at Parsons School of Design. After graduation and a brief stint at Interview magazine, Petronio moved to Paris, where he still resides today. He founded Petronio Associates in 1993, a creative agency with an impressive roster of clients that now includes Louis Vuitton, Yves Saint Laurent, Jil Sander, Miu Miu, and Comme des Garçons. The following year, he and Suzanne Knoller launched Self Service, a lauded fashion publication dedicated to celebrating a generation of young talent, who were yet to be embraced by industry gatekeepers. Self Service has also given Petronio the artistic freedom to showcase and hone his own editorial skill set, which also includes photography.

For 30 years, Petronio has captured the figures featured in the pages of Self Service in front of a plain, white backdrop, with a Land camera and FP-100 Polaroid film. With this consistent format, Petronio has highlighted the changing faces of industry catalysts, and created an extensive catalog of portraiture that chronicles three decades of evolution in art, fashion, and culture.

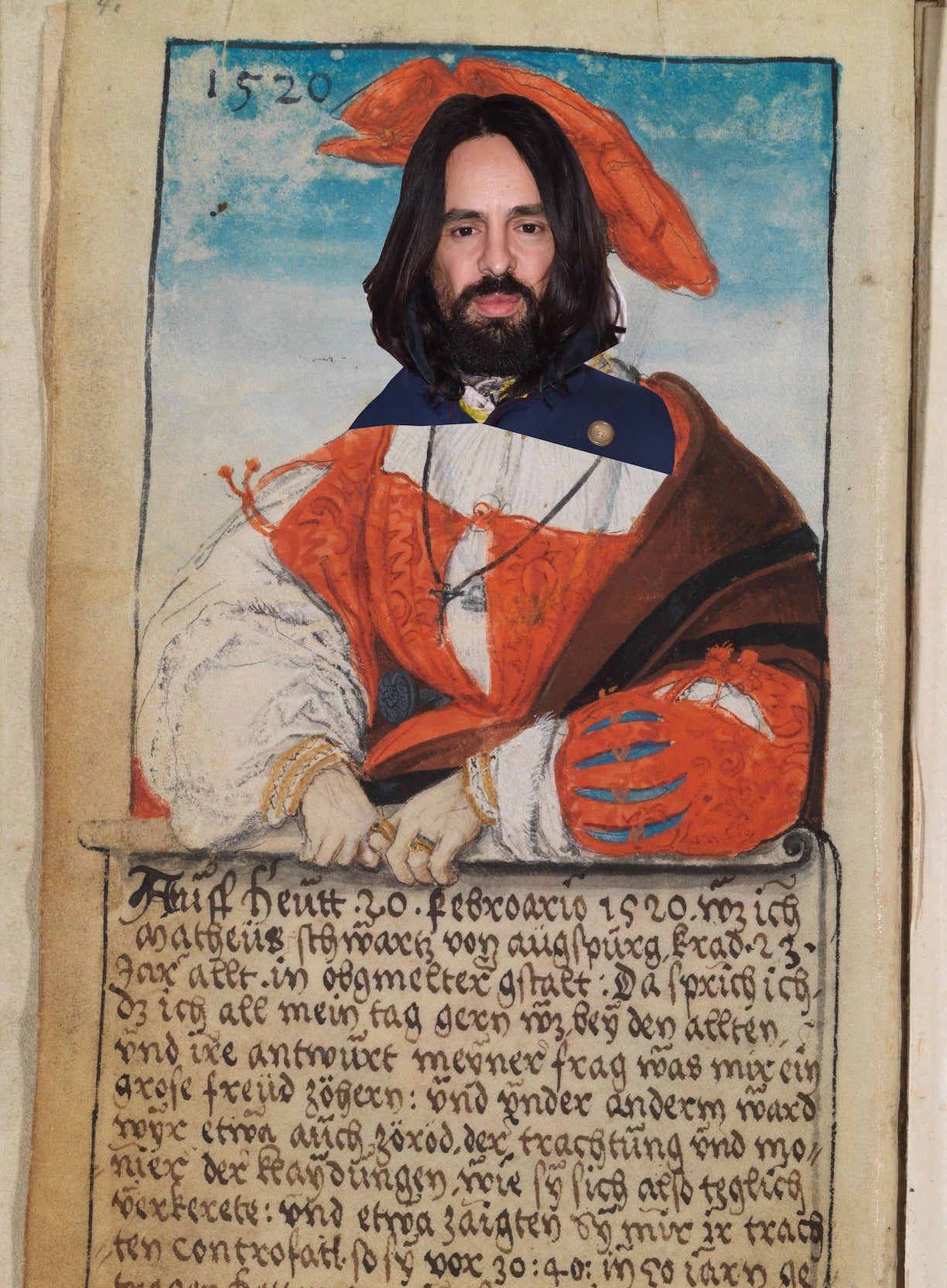

From now until February 22, a survey of Petronio’s photography is on view at Zurich’s Galerie Gmurzynska, in a two-part exhibition called “Stylistics.” With some of his Polaroids enlarged to unprecedented sizes (the largest are nearly two meters in height), Petronio has transformed the gallery space into a glamorous Hall of Fame. The “constellation of cultural icons” on display boasts the privilege of connection that magazine-making affords, and offers visitors a masterclass in the roles that coherence, consistency, and attention to detail play in creating imagery that is both impactful and enduring.

CASSIDY GEORGE: “Stylistics” is an impressive display of access to the creative elite. Anyone familiar with the complexity of interfaces like publicists, agents, and assistants knows that assembling a cast of characters that includes Donatella Versace, Karl Lagerfeld, Alexander McQueen, Nicolas Ghesquière, Kendall Jenner, and Anna Ewers is no small feat.

EZRA PETRONIO: It’s always a question of encounters. You meet people and they introduce you to more, and it grows like a spiderweb. Once you start documenting these people and immersing yourself in these different contexts, they become like little “happenings.” Looking back, it’s been a wild experience shooting everyone from underground architects and DJs in Berlin to Karl Lagerfeld at Cannes, or Jay Z backstage. The conversations have been lovely.

The show is really about the privilege we have to meet people, capture them, and create connections. That’s what magazines like ours are: a place of convergence of people and ideas. The project started with Self Service in the mid-1990s, because we had all of these crazy personalities coming through the office and we knew that we should document it. The show is basically a historical narration of that body of work, which gives you an idea of the range of creative minds we covered: designers, musicians, and artists, from the establishment to the avant-garde. In doing so, we’ve created a time capsule.

Why Polaroids?

I’ve been obsessed with Andy Warhol’s use of Polaroids as social documentation for as long as I can remember. Warhol inspired me to choose the Land camera, which has a lot of limitations. It has a fixed focus and everything is a single frame, so you can’t zoom in or out. All I really need is a white background. For me, portraiture is a very straightforward and direct process. It’s about taking the context out and focusing on the person.

You’ve found countless ways to play with these images in your layouts. How did you choose to exhibit them in “Stylistics”?

This show takes place in two spaces. In the first gallery, the Polaroids are shown at their normal size. In the second gallery, we took more of a fine-arts approach. We enlarged the Polaroids and created giant, oversized prints. When you see them at that scale, it’s a totally new encounter. You get to see all of the beautiful imperfections and all of the accidental, weird colors, the motion and emotion. Analogue photography is so chemically oriented, and I think it’s charming to see these images with all of this emulsion in such a digital era. We also tried to show some of my experimentation over the years. There are singles, diptychs, and collages.

Part of the artistry of portraiture is learning how to make people in a vulnerable position feel at ease. Does that come naturally to you?

Different cultures have different portrait traditions. Some are very cold and distant, while others are quite warm and personal. What you’re saying is true of all portraiture: the psychological component is half of the photograph. It’s maybe even the main ingredient. For example, if I’m shooting someone who is not self-confident, I can take dozens of portraits and the pictures won’t look good, no matter how beautiful they are.

The format also places a lot of pressure on me because we open the photos together, in real time. Polaroids don’t allow you to hide behind a screen or editing. Every moment is one of uncertainty and tension for both the subject and myself. If the person is not comfortable, or if I’m having a bad day, you can see it and feel it in the picture.

A lot of responsibility falls on your shoulders when you take portraits, because you have to create that trust – and often, that immediate trust. Sometimes I have an hour, sometimes I have five minutes, sometimes I do sessions with 20 people, and it just goes one after the other. I’ve shot over 4,000 portraits. It took time to learn how to make someone feel like they can let go in the moment and have faith in the collaborative process.

You had 4,000 people to choose from. How did you decide who made it into the show?

Of course, the more famous and recognizable people are in the exhibition, but we really made an effort to represent all of the creative fields and show a variety of characters. Even though 60 percent of the people I took portraits of are from the fashion industry, I captured people from all layers within the industry: hair stylists, models, designers, marketing people, CEOs. There’s no high or low for me. The richness and diversity is what makes it interesting.

Though the prompt is fixed, I imagine photographing such a range of characters has bred a dramatic range of experiences. Which stories stand out in your memory?

I remember every person, every shoot, and every situation. There were very few unpleasant ones. One time I waited four hours for Jean Paul Gaultier. He came in, didn’t say hello and just stood there while I took the photo. Then he walked out. I ended up with one Polaroid. But I’ve also photographed some geniuses who have been surprisingly nice. Shooting Louise Bourgeois at her brownstone in New York was a beautiful experience. There was a white wall above her couch, but it was covered with art and memorabilia. She asked her assistant to take it all down so that I could photograph her. I remember the assistant had white gloves on and was removing everything so carefully. It took forever! But in that hour span of time, I got to have this amazing one on one conversation with her.

There have been a lot of funny moments, especially when people come in prepared. Tom Ford, for example, knew my work. He studied the shadows and the style, and knew the exact position he wanted to be captured in. When I take someone’s portrait, I typically move around slowly and stop periodically to review. When I looked at the first batch of portraits that I took of him, I realized that he had moved with me to ensure he was in the pose he designed in every single frame. He had complete control. We laughed about it, and it became this fun game of cat and mouse.

There have also been a lot of funny locations, because I’m always hunting for that white background. I shot Vivienne Westwood in the toilets of Milan Fashion Week. I also photographed an amazing art historian at his home. The only white wall he had was in his laundry room, so he had to crawl on top of his washing machine in this little cupboard.

The show chronicles the faces of an evolving industry. What was the fashion world like in the early days of Self Service?

It was such a different dynamic! This was pre-Colette, pre-Eurostar, pre-internet. It was a very conservative time in France, even in the world of fashion photography and fashion design. There was no recognition of the avant-garde by the establishment, and there was very little intersection and connection between different industries. Self Service, and the wave of magazines that started at the same time, which included Purple and Dazed and Confused, set out to break those boundaries.

How would you describe the state of the industry today?

Right now, we’re in the device era. The entire system is being reconsidered. We’re in a sort of washing machine moment because there are so many new layers and complexities to navigate. Covid and economic pressures have created this general state of confusion. Streetwear has come in and changed everything. There’s also the problem of retail versus e-commerce. Influencer budgets are massive now, and big fashion magazines are going through difficult times.

Digital has set a new pace and things have accelerated rather quickly. People get out of school and get high profile jobs. They no longer have the time to find themselves and develop their body of work. For a long time, someone like Nicolas Ghesquière was who you looked up to. That was the model of success. Now, people look up to figures who have fast-tracked success.

Fashion today is about filling space and being in constant conversation with content, people, collections, and drops. The press is hungry for anything new. That’s generated a lot of hype for things that are very of the moment, but ultimately only things of quality will last.

How have these shifts impacted Self Service?

It’s funny to look back at our old campaigns, when we had four days to shoot three pictures. Those days are gone! Now, we go to set in the morning and have 150 assets to deliver: main print, main film, BTS, digital, gifs. We have to produce a huge quantity of things in very little time and for less money, but we have to keep the same level of quality and originality, despite the fact that the media we work with is constantly changing.

The intensity with which we have to work to be successful is far more extreme. It’s less enjoyable, but it isn’t necessarily less creative. But I think that’s the role of publications like ours: preserving creativity and creative thinking in this industry.

People in digital media sometimes consider the print world old fashioned, but Self Service has always embraced new technology. You did an iPad version of the magazine right after the iPad was released, made The Film Issue during the first wave of Covid-19 lockdowns, and have even experimented with augmented reality.

We don’t do it because it’s commercially relevant, we do it because we genuinely want to explore these things. Hopefully, we inspire others to do the same. The luxury fashion industry is actually quite late to the digital game, compared to other industries. At my agency, so much of my creative direction has been an attempt to change peoples’ mindset. Today, a successful campaign encompasses so much more than a billboard. Your Instagram has to be great, and your brand experience has to be really coherent across all channels. The most successful brands today are the ones that are coherent in everything they do.

Beyond coherence, what do you think is the key to success for labels in the “device era”?

Creating a brand identity that is easily perceived by mass audiences. For example, Gucci is about eccentricity. Balenciaga is about experimentation. Saint Laurent is about sexy black and white. People buy into what those brands represent, rather than what they are actually selling. It’s about values and associations, not outfits and products.

How can brands develop and evolve while maintaining that coherence?

It really depends. In a big brand, the decision making is limited to very few. But if there’s synergy at the top between a CEO, who has a strategic vision, and a creative director, who has an artistic vision – it’s magical. That is happening at Gucci and Balenciaga. Whether you like what they are doing or not, it’s coherent. The design on every asset, from an Instagram post to menu at a PR event, has the same level of excellence. Their messaging is consistent.

It’s a complicated task for a brand to figure out how to maintain their DNA while trying to appeal to the mindsets of new customers, and it's even more complicated for brands that are more unstructured or segmented. This younger generation is so overloaded with content and references that everything has become somewhat disposable to them. But they also have far more humility in their relationship to their environment and the industry, and care about things like sustainability and locality. They’re coming in with new, raw energy that’s unfiltered. I think finding talents who mirror that energy is exactly what magazines like ours are here to do.

Credits

- Text: CASSIDY GEORGE

- Photography: Ezra Petronio