A Film’s Sonic Architecture: DOUG AITKEN

A couple hours before I met Doug Aitken in Zurich, a friend, who was also in town for Zurich Art Weekend—which took place shortly before Art Basel—and I briefly discussed Aitken’s work over an Acai bowl. My friend suggested that I should inquire about Aitken’s relationship with MTV. I did not end up asking him about it but recognized the parallel between Aitken’s films and music video productions for the first time. We did, however, talk about music and sound as well as that the film he is currently showing at Eva Presenhuber in his show “Howl” has a musical architecture built within it. In this interview, we talked about the sound of technology and the art world’s migratory pattern.

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: The press release of your show proposes that viewers should think about pressing questions while engaging with the work. Which questions are these in particular?

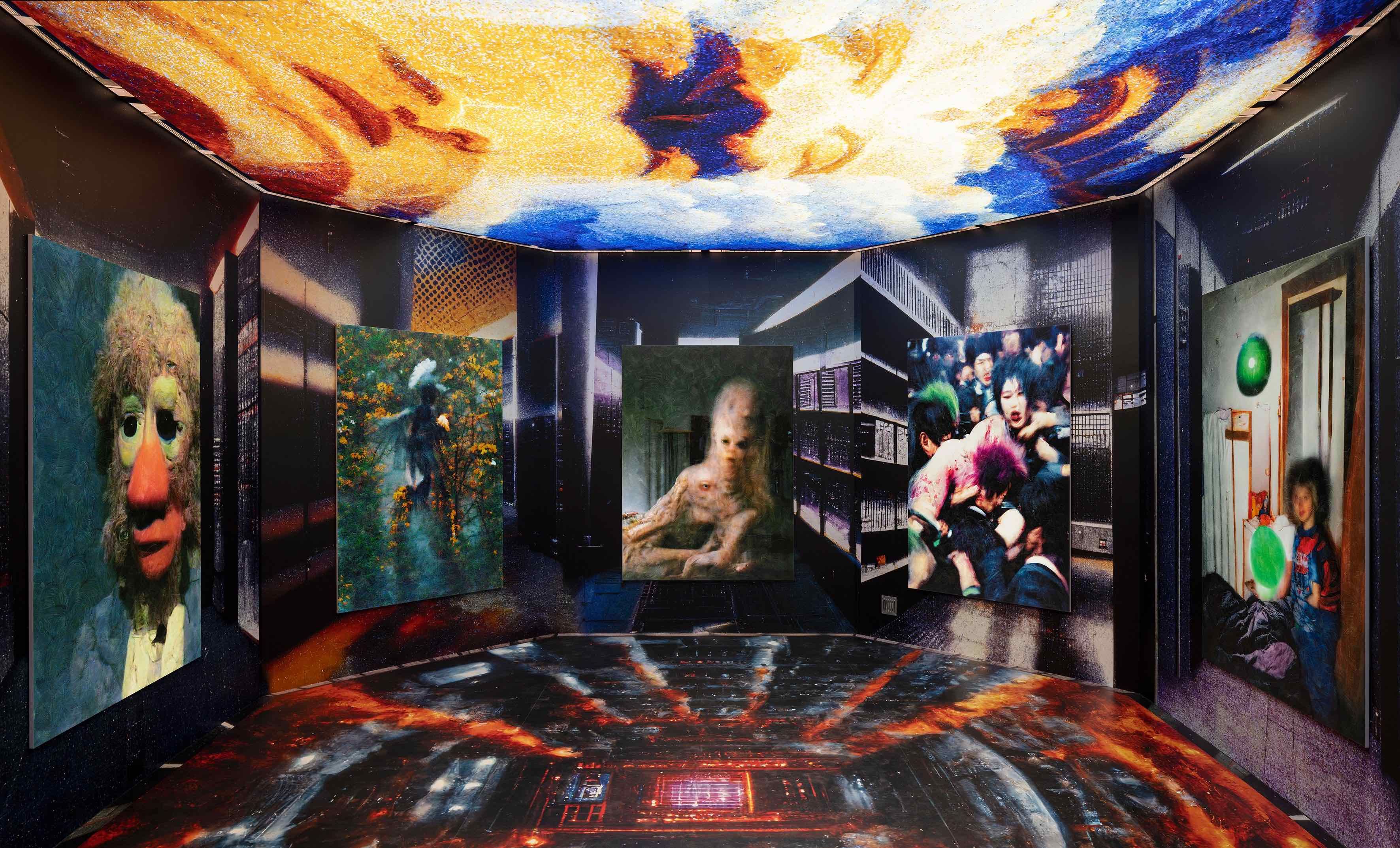

DOUG AITKEN: "Howl" is composed of a series of chapters where each room is exploring a different idea. In the final room a film installation tells a specific story that is simultaneously a universal one. It deals with a town in the US that was born in the early 20th century as a product of the mechanical revolution of oil, gas, and machines. A big part of the visible landscape has transformed from natural to mechanical. It poses questions around how we live in that environment, how we occupy it, but also where we go from there.

CKE: So, the video acts as a summary of the other exhibition chapters.

DA: They're all interconnected. The film installation wasn't made with an agenda or made with a script. I went out and actually discovered this place, spoke to the people there, and gave them a voice. Often when I asked questions, they'd say, "Nobody's ever asked me these questions before," or, "I feel like I'm never heard, I have no voice." The work is not really a documentary, it's more like a poem or musical composition that uses different people and creates a connectivity.

CKE: Do you find these people by accident, or do you choose them specifically?

DA: Well, I just find people and talk to them. You might be in a field, and there's a guy sleeping in his truck in an oil field. He wakes up, and you start talking to him. He wonders what you are doing. So, you tell him you're making this film, and you ask if he wants to be part of it. It was completely unscripted, raw, and spontaneous. That's why it took a long time to make.

CKE: Do you mean the video addresses universal questions that concern every human being? Do you explicitly intend for every viewer to be able to relate to these questions—and to the video, too?

DA: I think that a story that has a degree of intimacy or vulnerability can connect with you, whereas things which are generalized can't. With this piece, I'm not interested in making a documentary, and I don't want to make art that tells you how to think or what to do. I am interested in the idea that an artwork can provoke, and can create questions where there are none. I think about it like a nutrient that allows you to be stimulated in certain ways.

CKE: I remember a quote from the film where a woman said, "I live in the present," which made me think about if our current present is not simply a repetition of the past. The film works a lot with repetition as a stylistic device—both on a technical level but also in its narrative. But you can also think within the framework of repetition on a meta-level, since all these question around the ecological crisis have been addressed for years now, and we still don't seem to learn. Humans basically just keep repeating history over and over again.

DA: Repetition is a structure for this artwork, almost like an idea architecture. I was more interested in a specific spoken sentence, line, or word than in someone talking for 45 minutes. There's this interesting thing that happens with repetition in languages: when a word repeats, it changes meaning, or the nuance of the word's inflection changes as you hear it again and again. Sometimes words even disintegrate. I wanted to distill the language of the piece into short crystal ideas, instead of having a longer documentary format. Regarding the repetition of history, I ask myself if this is inescapable. Maybe we are in a feedback loop. This loop is a continual acceleration. We have a certain set of tools as humans, but how do we adapt to changes? How do we adapt to ChatGPT or the Apple augmented reality glasses that just came out? How do we keep adapting when the acceleration of innovation when technology moves so much faster than what we can absorb?

CKE: Talking about the architecture of a film makes the medium almost sculptural, where you have a kind of conceptual sculpture within the film.

DA: "Howl" sort of built itself. I didn't have a theme or concept when I started it. You edit one layer and then another layer and it would begin to build itself. I thought maybe we just need to approach this as a musical composition. It's liberating because when you aren't holding these massive stories, and you're able to create more room for ambiguity.

CKE: So, the film is a musical composition?

DA: In my mind, yes. I don't know if it is to you.

CKE: Perhaps the work is both sculptural and musical—they certainly have some overlap. Like in language. In another interview you said that you perceive language as sculptural, so it's somehow all intertwined.

DA: In the first room there's language as sculpture, and in the last room there's language in the air. On the one hand you have language in a solid form, as part of an object, for example a stone. On the other hand, you have liquid language as part of a moving atmosphere. All the music in the film we create ourselves. There is this interesting aspect you mentioned about repetition earlier. When we talk about music—and you live in Berlin where techno is almost like the architecture of Berlin—reduced beats or beat driven music happened before the industrial revolution. There's a lot of musicians I've spoken to who talked about growing up and hearing a factory or machine sounds outside their bedroom. In some ways, we humans are creatures who absorb what's around us. And the sound of technology is repetition. It seeps into how we think and what music we make. So, I started thinking about that idea of an invisible architecture, a sonic architecture in this film installation.

CKE: Thinking about that sonic architecture makes you realize that it's something inescapable, and that the power relations that architecture builds, supports, or enhances are also hard to escape. Since we're exposed to the "sound of technology" every day, I think you profoundly absorb the idea that you desperately need this technology, that there is no way without it.

DA: Maybe we need to step back to move forward. Maybe we need to not just stand at the horizon, looking and wondering. The piece would have been totally different if it was filmed in a hyper-new city, where everything is weightless and in the air. I think we need to reclaim an awareness of the space around us and recognize that we don't live a linear existence. It's not about acceleration and linearity. It's about a wider framework, a larger tapestry or connectivity with what's around us.

CKE: I think awareness is a concept that's especially popular in the art world. Everyone is aware that you don't need to fly to Zurich and Basel the week after, but everyone is still doing it.

DA: I think each every one of us is responsible for our actions, and what we can do to modify or alter our everyday actions is incredibly pertinent. In art, there is this kind of migratory pattern. People are moving nomadically to visit the next fair, museum, etc. So, there is this trail of a carbon footprint that the art world leaves behind. The other trail belongs to the art itself, which is often incredibly conservative art. It's formal, and it's commodifiable—an object made by a fabricator at a fabrication house that the artist has maybe never visited. But what happens if art changes its language? What happens if the materials are made where the art is shown? What if art is site specific, not just in a conceptual sense, but the ingredients and materials are made on-site. That's something that we are experimenting with at our studio right now, the thought of how we can grow art. That's a direction that we need to look at more and remove ourselves from this idea of containment—that art is a container for something, and something that should never change when it leaves the artist's studio.

Credits

- Text: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

Related Content

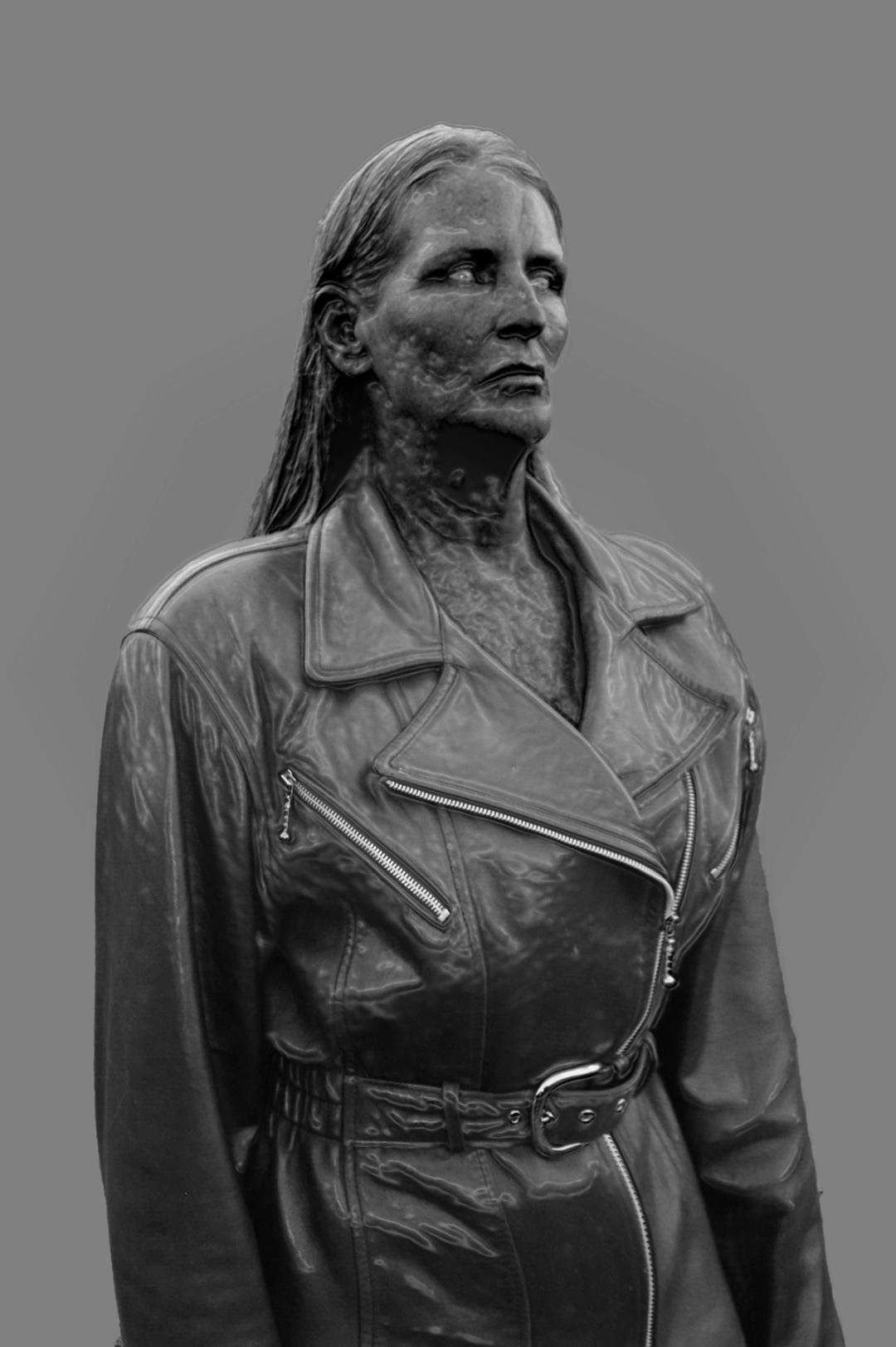

“It’s Like a Lighthouse”: DOUG AITKEN's Green Lens for SAINT LAURENT

BILLY BULTHEEL and ALEXANDER IEZZI: Sculpting Music in Churches

This Means DAWN: PACCBET Skate Film in Los Angeles

Art World Resorts: artgenève

Art World Resorts: On at Art Basel in Miami Beach

Finding Romance in the Grotesque: JON RAFMAN

Art World Resorts: No Utopias, but Chicago

KRISTINA NAGEL’s Landscapes of Depersonalizations