ZAHA HADID’S Posthumous Expression of Virtual Reality

|Robert Grunenberg

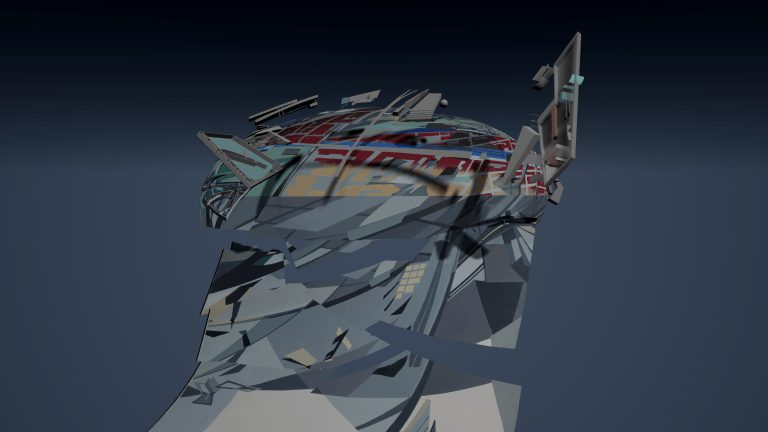

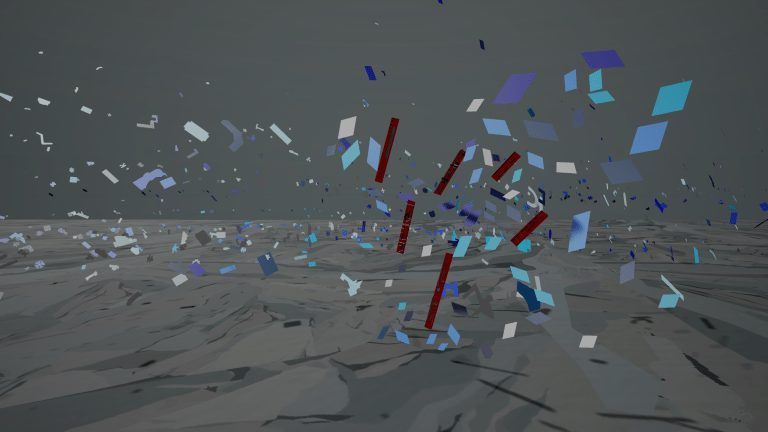

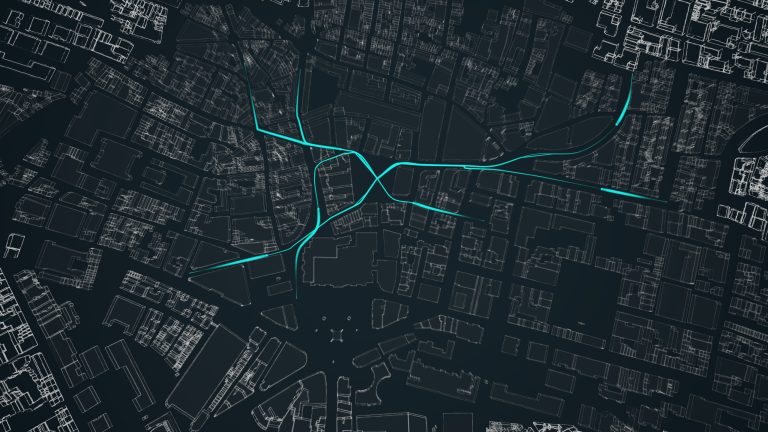

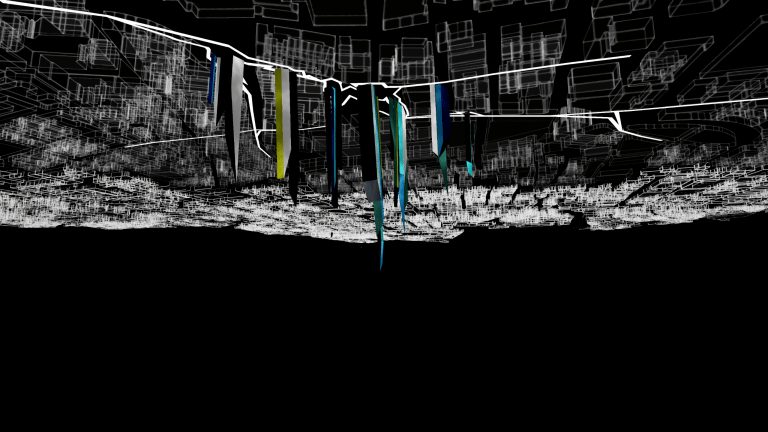

When Zaha Hadid passed away last year, the world lost not only a great architect but also a great artist. Since the 1970s, Hadid created a vast collection of paintings and drawings that were inspired by Russian Constructivism. The works are part of the exhibition “Zaha Hadid: Early Paintings and Drawings” curated by Amira Gad that recently closed in London and is now travelling to Hong Kong. In these lesser-known works, Hadid explores ways to override the principles of nature and gravity – ideas that would later be transformed into her bold architecture. Hadid’s paintings and drawings had remained unrealized until the Serpentine Gallery in London used virtual reality (VR) to breathe life into Hadid’s plans. In cooperation with Zaha Hadid Virtual Reality Group, led by Helmut Kinzler, and Google Arts & Culture, the Serpentine Gallery commissioned four experimental VR paintings that enable an immersive experience of Hadid’s practice. For 032c, Robert Grunenberg spoke to Ben Vickers, “Curator of Digital” at the Serpentine Gallery, about Hadid’s early paintings, the powers of VR, and its transformative influence over the art world.

Robert Grunenberg: Zaha Hadid once said, “I think there should be no end to experimentation.” Was that an inspiration for the show – to experiment and introduce virtual reality to a retrospective exhibition format?

Ben Vickers: That quote served as the mantra for the exhibition and led to the work with VR. Hadid’s practice with her early drawings and paintings starts in this highly speculative space. The paintings and drawings in the exhibition were a real revelation for me. None of the buildings they depict had ever been realized, all of them were produced prior the Vitra Fire Station. Which is very relevant to now, as at this moment in time we are highly aware of the emergence and influence of speculative practices in the art world. You see speculative design, architecture, fiction – there is a lot of speculation going on. If you look into the history of Hadid’s practice, what you see are these bold and what seemed like untenable propositions. But what is critical here for speculative practice is that she ended up realizing these very uncanny constructions that challenged engineering, architecture, and the way we think about buildings, and so much of this is a result of the digital turn in architecture.

Hadid’s use of perspective and space has a utopian spirit to it. Did she preempt VR?

Undoubtedly, the connection is clear, much of the motivation for working with VR is connected to those speculations and proposals for buildings. They preempt the process that you see in digital software: the ability to extrude, to look from different perspectives, the layering, the displacement, and the deforming techniques. All of these early works did that long before software was being used as a standard in architectural offices. Her work preempts the importance of the role of those technologies in architecture itself. In the mid and the late 90s, there was a dramatic move in most architectural studios regarding the digitalization of traditional processes of model-making and drawing and Zaha Hadid Architects were at the forefront of this shift, adopting technological processes from other industries. At the same time, Hadid’s ideas of buildings suddenly became real buildings, like the Vitra Fire Station in Germany from 1993. Those two things came together at that time. I don’t think it is an accident. Her paintings and drawings had a vision of the future, but she had to wait for it.

There is a wide spectrum of how VR is defined and treated in the creative disciplines. Often it is used as an add-on: You have VR architecture, VR art, VR fashion. How do you view VR?

I believe as Jaron Lanier stated at the onset of virtual reality’s development, that VR is its own discipline, its own medium. One that we are only at the very beginning of understanding. I don’t think these VR experiences serve simply as enhancements of Hadid’s paintings and drawings. Rather they are gateway points for accessing the growing depth of a constantly evolving practice. Technology is too often treated simply as an add-on that amplifies something that already exists. When you look at the works in the show and you think, “This is a proposition for a building,” that is already a virtual process that happens in the mind’s eye. The VR is acting approximately in that space, as a key to a new kind of sensory experience for the work.

Will VR disrupt everything we know in terms of exhibition space?

We’ve been waiting years for VR to arrive. At some point I didn’t think it would. About two years ago, when the first VR headset got crowdfunded, a lot of the technical problems that had prevented the first round of VR succeeding in the 80s and 90s, seemed to have been miraculously solved. The development since then has accelerated at such a fast rate, which is actually a result of the global success story of mobile phones. Mobile phones made everything so small and developed many parts of hardware. Without the mobile phone, we would never have had VR hardware. Ultimately, it made VR affordable. As a result of that, we suddenly accelerated into this space where VR has the same level of disruptive quality as the early Internet. Now we have this new spatial environment that will change how we learn, how we connect with one another and continue to collapse an embodied sense of temporality – we literally have no way of being able to predict what the impact of that will be on our lives, let alone the exhibition space.

When I tried the VR and entered Hadid’s VR experience of the painting Leicester Square, 1990 – Blue and Green Scrapers, 1990, it blew my mind. The space, the motion and the sound, the whole sensory experience was so immersive and very powerful.

With the Leicester Square work, you experience a drop of several hundred feet, which makes your stomach turn slightly, as you would naturally expect from such a drop. You have an extreme physical response to this painting that in many ways encompasses the scope of its proposition. I think within the next decade, our perception of reality is going to be very different to what we anticipated prior to the arrival of VR, and those kinds of physiological reactions are an early stage of building a new vocabulary for the senses.

What will its impact be for the art world?

We’ve been researching VR for the past two years and have been in touch with all these vanguard areas of VR development – like construction, porn, and gaming – in order to understand what the possibilities and limitations of the technology are. It’s interesting that curators rely on very particular narrative scripts for working with the traditional gallery space. Almost every art show in the world responds to the art historical script of the white cube. And so VR presents real difficulties here from a curatorial perspective because it suddenly moves you out of that space. So you have to ask yourself: what is the context or narrative structure of the VR space? Are we going to apply the white cube as the contextual environment? Obviously that’s completely stupid and embarrassing because you have a technology that enables you to create any context you can imagine, why would you select the confines of the white cube? With the introduction of any alternative script or narrative context, the role of the curator or even museum for that matter begins to take on very different meanings and skill sets.

And individual artists won’t only use VR to show their art, but also create art within a VR space.

The creation of art in VR – in the metaverse – is something I’m particularly interested in at the moment. The platforms though, are only just arriving. There are two companies that are leading the metaverse space right now: JanusVR and High Fidelity, the latter by the creator of Second Life. I haven’t come across any artist yet that works in there. I’ve had some meetings with artists in these metaverses, but it’s so new and there are a lot of restrictions. The cost of consumer VR for these kinds of environments is still far out of reach for too many people – which is one of the reasons we chose to release a version of the in-gallery experience as 360 videos.

All of these changes you have to think about as a “Curator of Digital.” This position was created when you started working for the Serpentine Gallery. What does a “Curator of Digital” do?

I have been working at the Serpentine Galleries now for about three years. I initially joined as a part of an ongoing conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Artistic Director of the Serpentine. We talked about what the impact of technology and the Internet would be on the museum and the gallery system. And what its relationship would be to the new media movements that had been before it. In the mid 90s to early 2000s you had the Net Art movement. Not everyone had arrived on the Internet then and it was possible for the museum and gallery system to ignore and discount the importance of technology and the Internet because there was such a limited audience, which is a real problem in terms of a historical gap. But by 2010-2015 there was a dramatic shift. Suddenly, there was an expectation from the public and artists that the galleries engage this area. Since then, a consensus has formed that these technologies should be used to create greater access or be considered in the augmentation of the art experience. My role is focused on a continual adaptation and meditation on the emergence of advanced technologies and their relationship to art production. Like the technology, my job continually mutates and transforms in response to this. Which is particularly important given that the art world, generally speaking, has always been suspicious of new technologies.

Why is the art world so suspicious of technology?

On the one side, artists have always represented the avant-garde and the innovators. If you look back at art’s history you find individuals who are extremely forward-thinking, like UBERMORGEN’s vote-auction who change our relationships to technology. On the other side, you have art institutions, who have been continually slow in adopting, responding and integrating technology. Predominantly because the museum’s role is to preserve knowledge and material over vast periods of time. This presents particular issues in respect to artwork made from or with technology.

How much do the art world and its artists rely on the tech world?

This is an interesting question because on the one hand tech companies have created their own cultural spaces – in a way, they have their own art world. The Burning Man festival is in many ways the Venice Biennale of the tech world. The art of this world often involves bold, complex, and large engineering feats. And I think many of those groups don’t necessarily see the need to participate in what many would view as an archaic and traditionalist contemporary art world. But having said that, I think this attitude is beginning to shift. And that we’re beginning to see a return to collaborations between artists and engineers that resembles historical precedents such as the work done at Bell Labs and the formation of groups such as E.A.T. by the likes of Robert Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver. What we focused on with Zaha Hadid Architects and Google Arts & Culture is a prime example of these kinds of collaboration and bringing many different actors together, a plural approach that is very much what we’re focused on at the Serpentine going forward.

What technologies are you excited about right now?

I think we’re in a very turbulent moment right now with respect to technological innovation. But I see a set of technologies on the horizon that are likely to be as impactful as multiple internets arriving all at once. Namely blockchain, augmented and virtual reality, robotics and drones, and AI, or specifically machine learning. This set of technologies spell out a time of enormously disruptive and extreme technological change – that is mirrored only in its extremities by recent political events. We don’t even know what any one of these individual technologies mean in combination with any one of the other technologies. It’s an exciting and terrifying time for humanity.

Writer Douglas Coupland once said “I miss my pre-internet brain.” Do you ever get nostalgic about a time before the Internet?

I am never nostalgic, but I am conscious that it is important to respond to acceleration. Despite being more embedded than most in these technologies, I’ve responded personally in the spirit of luddism. Becoming extremely protective of my time, through strict monastic routine and the information flows I allow into my life. Being someone who is heavily involved in technology, I take it more seriously than ever. I’m especially conscious of the effects on my attention span, so I cut out almost all social media and information flows subject to manipulation. I meditate in order to have a closed and focused inner space. I think it is an essential fluency for surviving the next decades and what is to come.

Credits

- Interview: Robert Grunenberg