Worldbuilding With Daisies

|Paige Silveria

Daisies x Salomon zine by Paige Silveria

"The way atmosphere, architecture, and sound design shape your sense of space has really informed how I think about world-building and composition in my own work," London-based artist Lucas Dupuy explains. "What I find interesting about [video] games in general is how they construct worlds you can attempt to inhabit, even if only temporarily. They make you think spatially, narratively and emotionally at the same time."

Artwork by Mathis Altmann

I loved hearing this, as it mirrored my own thoughts when abstractly constructing this “DAISIES” group exhibition over the summer. With the help of many friends, the result was my first “DAISIES” group show in a couple of years, presented by Salomon Sportstyle and hosted in Dover Street Market Paris‘s 220m2 B2 project space. A seven-piece custom sound score by Montenegrin artist Regis reverberated throughout the dim room and the cooly lit modular walls featured work by Camille Soulat, Charlotte- Maëve Perret, Jack Warne, Lucas Dupuy, Sara Yukiko, Mathis Altmann, Melchior Tersen, Christie MacDonald, Nicolas Zanoni, Pierre Touré-Cuq and Lisa Boalt. At the opening reception, New York-based Gabrielle Schwan performed a specially choreographed piece within the space in an iconic Noir Kei Ninomiya look.

For some background, I founded the DAISIES project in New York in 2018 with an exhibition sponsored by Nike in the basement theater The PUBLIC Hotel featuring work by artists such as Julia Fox, Alana O’Herlihy and Marland Backus, alongside live music by artists like Okay Kaya. Since then it’s shown work by Larry Clark, Frank Dorrey, Bill Strobeck, Sandy Kim, Sang Woo Kim, Julian Klincewicz, Eri Wakiyama, Thibaut Grevet, and more in Miami, LA, Tokyo, Paris and Biarritz, and expanded into a range of collaborative clothing releases, art-book and object pop-ups, publications, parties—even a live-stream TV show at one point.

To delve into the world-building of this most recent iteration, I spoke with three people who made custom works specifically for it: sound designer Regis, artist Lucas Dupuy, and dancer/artist Gabrielle Schwan.

Artwork by Melchior Tersen

SOUND: RELJA CUPIC AKA REGIS

Paige Silvera: Tell me about yourself and your upbringing.

Relja Cupic: I’m from Katunska Nahiya, in Montenegro, a tiny country where the nature’s unreal. Growing up was a blast, even though we have a super traditional vibe, and I never really fit in. I was kinda wild—not rude or disrespectful—but always looking to cause some damage or chaos. My best times were in my grandparents’ village, where I had total freedom. They’d blast RCG [Radio Montenegro] all day, which used to annoy me because I couldn’t stand turbo-folk or traditional tunes back then. But when I started producing and composing, I unconsciously started pushing those melodies into my stuff. Now I get that my music is inspired by those Balkan vibes and songs they played. That melos is in my bloodline. Back at my grandma’s place of total freedom, my uncle lived with them, he was a DJ with a serious sound system; that’s where I found Danny Tenaglia, The Prodigy, and Sepultura. My grandma lived in a huge brutalist block. Out front, the older cool guys blasted hip-hop and rave so loud the whole neighborhood bounced. I was always trying to flex and show I could hang with them, so I’d drag my uncle’s speakers to the window, crank the music to max, and then head downstairs to chill on the bench. In the teenage period, I was obsessed with sound system culture. I even hosted a radio show that was my first professional step into music. I’ve always been about the beat and the instrumental—not the lyrics though, just the melodies. It’s still the same today. I need like three listens to finally catch what the artist is even talking about. That’s why I love instrumentals so much. I have a bunch of files of just instrumentals from cool songs.

PS: Outside of your grandma’s block, what was the music scene like in the Balkans?

RC: Montenegro’s scene was small and not progressive. I couldn’t find anyone with similar taste to start a band or duo, which was discouraging. We’re generally a closed society, hard and slow in accepting new trends. I think it had something to do with history since we were surrounded by big empires like the Ottoman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and they did not allow any goods inside. For a while, we barely had a way to the sea, and people developed resistance to new things. It’s in our genes. Belgrade changed everything; it’s the cultural capital of the whole ex-Yugoslav region. The scene there was alive and fun; I could finally play what I liked without someone asking, “Can you do minimal or deep house?” So, I was lucky to meet my brothers from Mystic Stylez and become a member. There were nine of us. And everyone is a killer DJ with their own style. I learned so much from them. It was a music collective commenced in the 2010s that revolutionized the bass-driven dance music scene in southeastern Europe

By the way, the first cassette I ever bought when I was about 10 was Will Smith’s “Miami.” Afterwards, my dad took me to his friend’s pub and the bartender played it loud, and the whole place started laughing like, “What the fuck what did you buy?”—even my dad was laughing at me.

PS: What about the cassette made you want to buy it?

RC: In the beginning, I started paying attention more to rap rave tracks from VIVA (German TV music station). When it was the time to buy my first cassette, I was looking at a huge wall of thousands of releases and I didn’t know a single artist. But then I recognized a guy from the movie, Men in Black (1997), the only familiar face. I was like, “This is it!”

PS: Can you tell me about composing music? What’s the process like?

RC: When inspiration hits, I have to jump on a computer, or I do a voice memo on my phone. My primary production technique after chords involves using a microphone to sing melody ideas, which I then convert into MIDI data for use as input across various instruments, often incorporating live recordings and instrumentalist interpretations for a richer, layered sound. Music has provided me with the tools to articulate the emotions that are my primary muses, often being nostalgia, pain, suffering, and euphoria.I had the privilege to learn from great Balkan composers and producers while collaborating with various studios in New York, Paris, and Belgrade. I’ve learned all sorts of techniques.

PS: How did you score the “Daisies” exhibition? There are so many different elements in this particular piece.

RC: I made like 10 demos and selected seven that were the most melancholic and dark to put into the full album. Working on it reminded me that as a kid I was obsessed with Chopin’s “Funeral March.” I also always wanted to work with a professional mourner, here we call them narikače. They sing loudly and cry at funerals. You can hear that vibe in the first piece, “Katunian Elegy.” In my personal life, I’m currently closing one chapter and opening another; that energy shaped the album. The whole soundtrack for the show is divided into the seven separate tracks from the album, which is also called “Katunian Elegy.” (Linked here and here.)

PS: What other kinds of archived files do you have?

RC: My archive is so diverse that I think it would be smarter to use other aliases. Mostly, I make ambient or beats. I record club tracks too and a lot of live instruments and vocals from trance to turbofolk.

People sometimes get confused by the range in my music. A lot of unreleased music I’ve made in the last 10 years has mostly an experimental/film vibe, which I present at my dynamic audiovisual, multisensory live performance The Gateway Program. The next one that I’m presenting is at artist and curator Korakrit Arunanondchai‘s Ghost Festival in Bangkok. There is a song that’s a part of it called “Cover yourself in the name of Allah” that draws inspiration from samples taken from a Balkan Muslim girl’s educational video, including repetition and lyrics about modesty and honor, which evokes a complex mix of emotions for me.

Daisies x Salomon zine by Paige Silveria

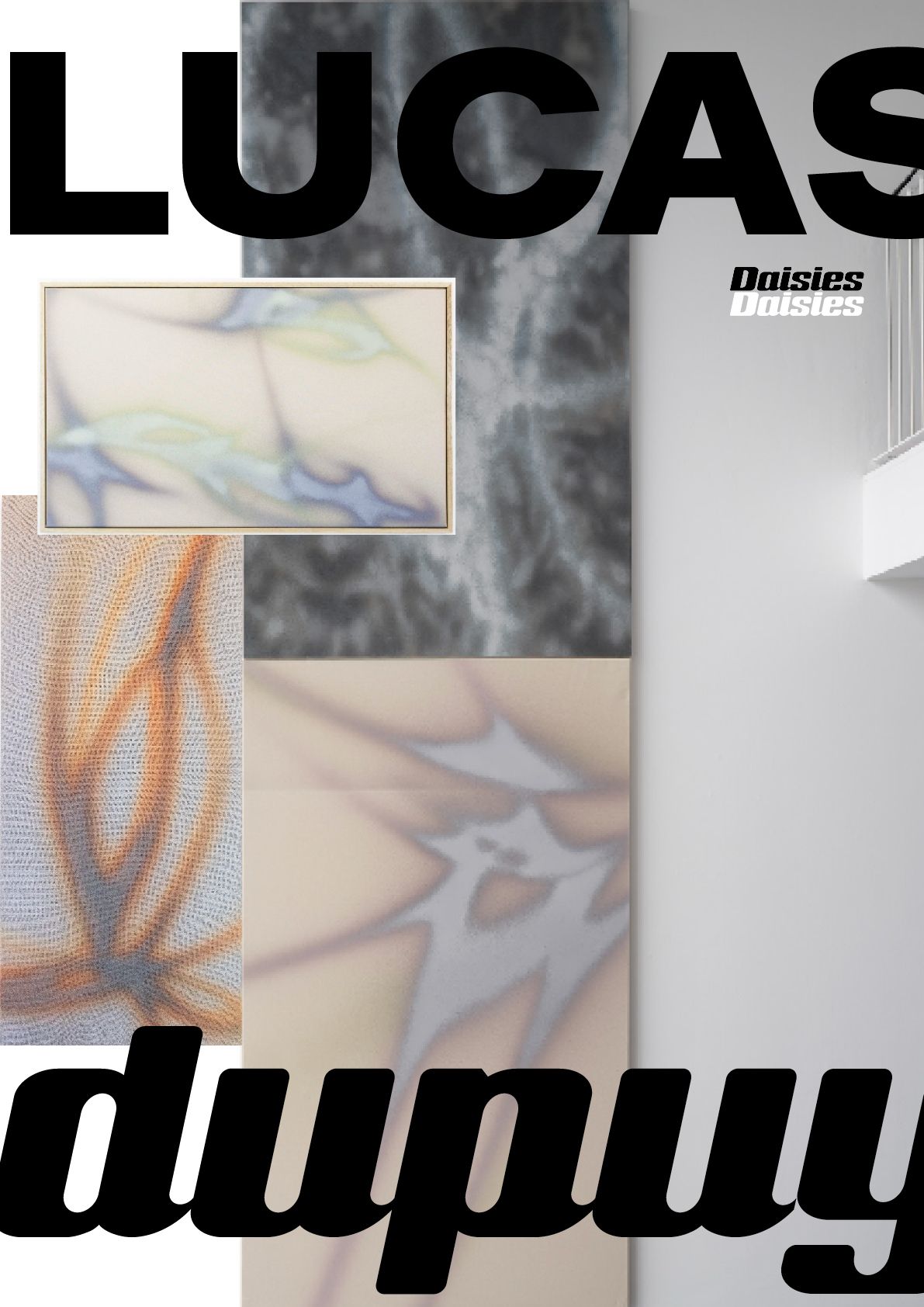

ARTWORK: LUCAS DUPUY

Paige Silvera: Tell me about your childhood; where are you from and what were you into as a kid?

Lucas Dupuy: I grew up in a place called Nunhead in South London. I feel very grateful to have grown up in such a strange, wonderful city. The vastness of it partially makes it strange and overwhelming. The people make it wonderful. It’s definitely informed my practice in many ways. It gave me access to its energy, but it’s also slower, which balanced things out for me. I still love it around here—I actually live just ten minutes away from Nunhead now. I grew up skateboarding as a teenager and that really opened up many doors and avenues in the city. Through that, I got to know lots of different people, places, and subcultures.

PS: Did skating inform your artwork at all?

LD: With skateboarding, you naturally develop a resilience to failure. That mentality carried over into my art practice from a young age. In the studio, failure is a huge part of the process: remaking things over and over, learning through mistakes. Especially in the works I produce now, I’m always looking for the somewhat “perfect” composition. I’m constantly working on paper, making hundreds of studies and drawings, exploring different frameworks for the paintings. It’s a very iterative, almost obsessive process, but it keeps opening up new possibilities.

Music also became an important part of my life from an early age, shaped by the different influences around me. I developed a particular interest in ambient music and dub techno, and those sounds have become very important to my art practice.More recently, I’ve started working on my own music and sound projects alongside painting. I have a solo show coming up in New York at Island Gallery, where I am collaborating on a sound piece with DJ Trystero that will be shown alongside the paintings.

PS: How did your practice develop?

LD: I think it developed in quite a natural way. I’ve always been making things in one form or another. Drawing has always been a large component, and research is another important part. I spend a lot of time collecting books—mostly from markets, AbeBooks, and eBay. Vauxhall Market in London has been an especially important place for finding books; I go there most Sundays. Most weeks, I come back with nothing, but sometimes there are stacks of magazines and rare finds. My friends Bruno and Daniel run a shop called Perfect Lives, which has an incredible selection of reference materials and artist monographs. I visit often to buy and look at books; the ritual of searching has become part of the practice in many ways. Some of the themes I return to include fractal image compression, meteorology, climatology, UFOs, crop circles, and architecture magazines. They all connect through patterns and structures. These references have been a key development in my practice and help develop compositions and motifs within the works.

PS: You can see those references in your work and get a feel for you nerding out a bit.

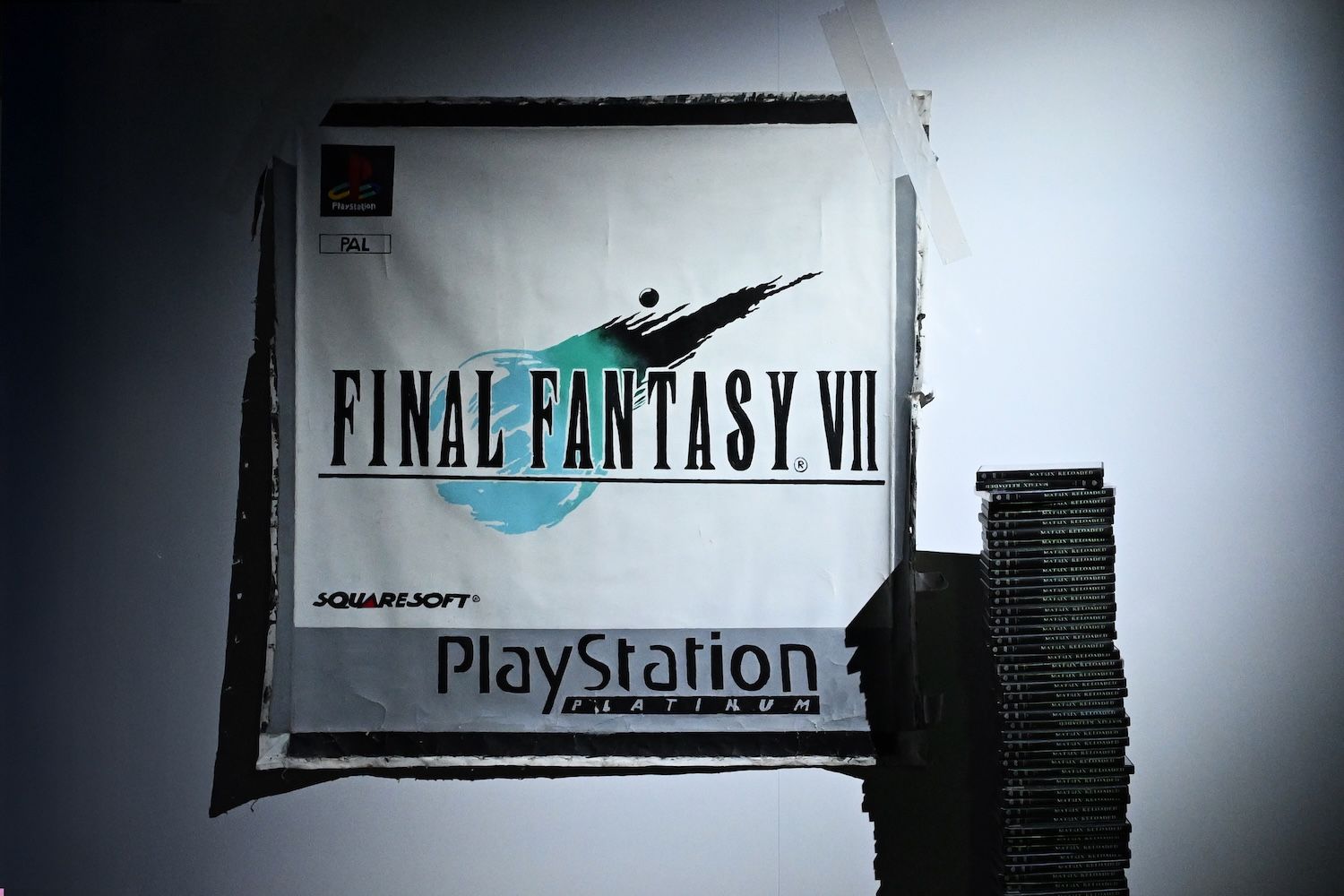

LD: I do nerd out on many things. I was recently included in a duo exhibition with H.R. Giger in Basel, which was a very special experience. To be paired with someone I’ve admired for many years was a real honor. Giger’s way of combining mechanical and organic is so influential. I also collect animation cels. I’ve long been interested in that way of working and the process behind it—the limited color palettes, the layering, and the discipline of drawing for moving images. That connects in some way to video games, which also play a huge role in my practice and research. Half-Life 2 (2004) in particular has been very influential. The soundtrack, paired with the environment the player experiences, is so good. The way atmosphere, architecture, and sound design shape your sense of space has really informed how I think about world-building and composition in my own work. What I find interesting about games in general is how they construct worlds you can attempt to inhabit, even if only temporarily. They make you think spatially, narratively, and emotionally at the same time. That’s something I try to bring into painting—not to recreate a game, but to capture that layered experience of space, emotion and movement.

PS: You mentioned in another interview that you spend a lot of time exploring and cycling around the city and countryside, photographing things that you later reflect on for your paintings. What kinds of spaces do you seek out to mine for this kind of imagery? How does it translate into your work?

LD: I take a lot of photos—compositions, materials, textures, and color relationships I come across while moving through different spaces. Sometimes, it’s just the way the evening light falls on a surface, or how light moves through leaves. I seek out spaces that I tend to spend lots of time in, I guess. They can be a forest in rural Sweden or a junction box on Old Kent Road (a very busy road in London). These elements that I photograph become part of my visual library (a hard drive of endless photos). Later in the studio, they resurface as triggers or starting points for paintings. It’s less about direct representation and more about the feeling or emotion that these details or motifs can create. Since I work with abstraction, having this library of images is crucial—it keeps me developing new ideas and compositions, and ensures the work doesn’t become too closed in on itself.

PS: For the particular three-part piece, Mass Transit Railway that’s included in this exhibition, how did you approach its development?

LD: I’ve recently been working with two- and three-panel formats to create single works. I’m really interested in how these structures can create rhythm, but also how they can feel alien or unfamiliar when abstracted in some way. For this piece, I wanted the viewer to move between the panels almost like chapters in a book, each offering a different angle or emotional state, but all connected. It’s less about narrative in a literal sense and more about creating a rhythm.

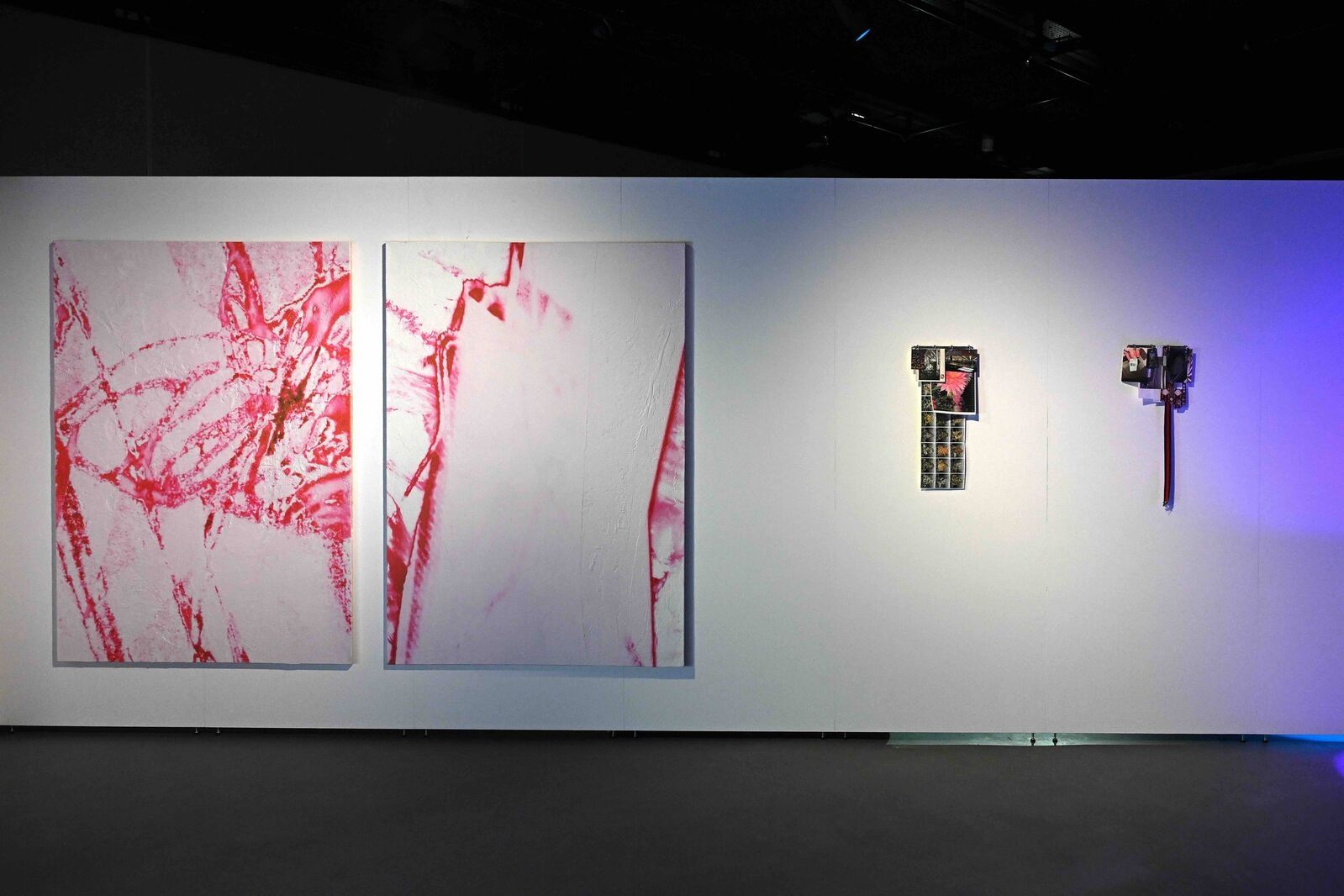

Daisies installation view

Left: Artwork by Jack Warne

Right: Artwork by Charotte-Maëve Perret

DANCE: GABRIELLE SCHWAN

Paige Silvera: Tell me about young Gabby.

Gabrielle Schwan: I grew up in a small city in Washington. It was pretty suburban but most of my time was spent in a ballet studio. I was super driven from a young age and loved learning anything new, often reading when I wasn’t dancing. My friends and I were also always playing dress up. You could usually catch me running around in some kind of costume. We would create dances and videos in our spare time. I think we really missed our TikTok era.

PS: I can definitely see this.

GS: It was mostly Halloween costumes, like animals. This one dinosaur pajama costume in particular was my favorite. I’d wear that regularly. Lots of princess dresses and tutus. I had racks of costumes and I’d force my friends to put them on when they came over.

PS: When did you discover the world outside of Washington?

GS: My parents liked to travel and we went on a lot of adventures. At first, it was to major cities around the US and then more around the world. It started with New York City and Hawaii, and then we went to the Baltic Sea, Germany, Poland, Dominican Republic, Jamaica. I got to go to Russia and that was so cool, seeing the ballet in St. Petersburg. The theatre was insane. So, travelling outside of Washington was really important to discovering more about the arts. I wanted to keep something from every place I went and started a collection of plushies, dolls, toys, or whatever from everywhere I had been. I loved that they were so specific to each country. They were all pretty cool and sometimes weird, or just totally different from what I was familiar with. And I think, even as a young kid, these small cultural experiences gave me a different perspective on art and cultural objects—especially before the internet and social media.

PS: What’s it like being a dancer today? The lifestyle of a ballerina seems so hardcore. It’s so impressive how you’ve maintained such a strict discipline, like when we went to Tokyo for just like 10 days for one of the Daisy group shows and you found a class to go to there. What’s your schedule like when it comes to training? Because you’re also taking college courses too.

GS: It’s hard to get away from it when you’ve grown up with it. I’ve taken a dance class almost every single day since I was young. I began dancing when I was two years old—though at that age, you’re obviously not doing much yet. My mother and grandma were both dancers. I remember finding my mom’s point shoes when I was too young to have tried them yet and putting them on and trying to figure out how to dance in them. It wasn’t until I was maybe 10 years old that they started to push me to train hard. When I was in professional programs, we’d dance about eight hours every day. So, it’s really all I’ve known. Most freelance dancers don’t go so often, but I’m just crazy and I like to be able to take class every day.

PS: How often do you perform in front of audiences?

GS: I want to more often, but it’s a bit harder to navigate performing sometimes if you’re not with a company. And sometimes you can get into productions like The Nutcracker as an extra, but I haven’t really focused on the performance aspect of it as much. It’s like interviewing for jobs.

PS: Yeah true. It’s not very common, at least in New York, to go and see dance performances in smaller theaters or without a big production behind it. How do you think ballet in particular is perceived today?

GS: I feel like we became a part of the conversation a couple of years ago because ballet core became popular in fashion. As demeaning as that is in a way, this social media aspect brought people’s attention back to the art, and some professional ballet dancers had a spotlight for a minute. In a way, that went against ballet culture, but at the same time, it also brought awareness and probably got more people out to go see shows and to support the art. So, I’m for it. But I definitely hope it wasn’t just a trend that’ll be over as soon as we stop wearing this style.

PS: You’re also well known for your textile clothing and art-object designs, especially those you’ve knitted. How did you learn those?

GS: My grandma taught me when I was really young and I never really stopped. Now it’s like second nature. I don’t even make a sketch or draw out what I want to do. I just start without thinking and play around with different ideas and change things around.

PS: You knit so quickly. It must be like muscle memory, taking something apart and then putting it back in another way with such ease. I love how you always take your knitting bag out in public with you too—which of course is usually an oversized orange Cabas cassette padded Bottega bag. You’ll literally be sitting at Lucien or a bar or whatever in the middle of a party with your crochet kit out.

GS: If I don’t have any real plans and I’m just stepping out, I’ll always bring it just in case. I can be social, but it definitely helps me sometimes to be comfortable in a big crowd. Especially in a new environment or around new people, when I don’t want to or know how to make conversation. It’s a way of being present without having to fully engage.

PS: There are so many weird things to create textiles out of, like those TikTok videos of people creating thread/yarn out of their own hair or their pets’ fur and turning them into hats and sweaters.

GS: Yeah, those videos can feel pretty performative. That said, as I’ve been regularly dying my hair orange for years, whenever I get it cut, I always save the hair.

PS: Wait really? You’ve still kept it?

GS: Yeah. I mean, it’s never that much because I don’t get that much cut off. But it always looks cool with the bright orange. So, I save it. I don’t have much yet, but eventually…

PS: I love the sustainability aspect.

GS: Yeah. Old t-shirts are also great to use to create knitting materials. Tights are fun too, because they’re elastic and people are always throwing them away if they get holes in them.

Artwork by Camille Soulat

Credits

- Text: Paige Silveria