WHAT IS RADICAL?

The word “radical” sometimes feels historical – like a Theodor Adorno bumper sticker pasted on the ass of a bygone revolution, or a stamp of approval from a dad who used to surf before he got fat.

And yet, whatever “radical” now is, it still has an energy that we crave and seek to apply to our projects. Furthermore, as the booms and busts of our convergence culture accelerate to the point of incomprehension, we sometimes stop to wonder: Is “radical” here to save us, or destroy us?

In search of the radical, six months ago, we contacted a group of friends, collaborators, and people we admire to ask them a simple question: “What is the most radical thing you’ve encountered in the last six months?”

The answers were published in 032c #29 in late 2015, and are presented below. They serve as a time capsule, marking this tumultuous decade’s mid-point, or as a time-bomb, ticking to the present.

Cyprien Gaillard – Artist, New York/Berlin

Georg Diez – Journalist, Berlin

What is missing today is a vision of time as moving forward. Of the future as a place you want to inhabit. Of the future as a place that actually exists.

Communism is an idea rather than an option. Remember, this is not about right or wrong. It is about what works. And so the only plausible utopia is a technological one. Which is not as new as it sounds. Still, it is not clear what it actually means. Computers replacing humans. Or, computers freeing humans.

And here it becomes interesting. As in any utopia, there is a dystopian element present. But even this negative energy has an appeal that is stronger than the stagnant atmosphere of a contemporary state of mind stuck in what Mark Fisher calls “capitalist realism.” A void, un trou, the French would say: time not even standing still; time absent.

The positive twist is an old dream of the Left of a certain kind: technology freeing people from work. For this, not only is a new economic model necessary, there needs to be new ways of organizing and thinking about things.

What is necessary, in short, is a philosophical move with a truly Copernican feel: turn the direction of time around, give the arrow new force, find a horizon that is worth reaching for.

Change, after all, is not only possible, it is inevitable. It is just that the face and nature of this change is unknown at the present. So when politics is stalled and the imagination is in a constant nostalgic loop, the job of the philosopher is to move ahead and look back at a present that maybe never was.

We have to learn how to chart the uncharted territory again. We have to learn how to speculate. This is the program proposed by a group that maybe is no longer a group, all part of a movement that is maybe not even a movement, named or not: Accelerationism, Speculative Realism, or something else.

Time here is moving forward. You can see it in the terms of that shift, the ground that moves. To me, that is radical.

Elie Ayache – Writer/Financier, Paris

The most radical thing I have seen in the last six months is the destruction of the Palmyra temples by the Islamic State.

Ilja Karilampi – Artist, Berlin

Zaina Miuicca’s (@zaina) Vine videos are out of this world, actually let me re-phrase that: her whole existence just captures my attention. I don’t always get what she’s about, but the highlife atmosphere she radiates through the clips is 100.

It either has to be that, or the fact that British producer Faze Miyake has such an ingenious sense of humor on Twitter and Instagram, which goes very well against his “boss don” grime wave.

Chris Dercon – Director of Tate Modern, London

The most radical … Sitting in the plane to Istanbul, next to a mannequin by Isa Genzken coming alive.

FEVER ROOM BY APITCHATPONG WEERASETHAKUL IN KOREA. A FEW DAYS AGO!

“It is a challenge for me to create a work that evokes layered dimensions on a flat medium such as cinema. I am thrilled to have an opportunity to explore this concept in a format that is new to me: theater. The first idea that comes to mind is to infect the theater audience with some kind of disease.” – APITCHATPONG WEERASETHAKUL.

Jack Self – Architect/Theorist, London

Without any apparent conflict, both Islamic State and a bathroom superstore can lay claim to “radical vision.” The ease with which the word encompasses both the barbaric and the banal hints at the crisis of radicality today, the dilution of its power, and the proliferation of its interpretations. In recent years, the radical has succumbed to an immense barrage of humorless hyperboles and exhausted clichés, manipulated into contexts it was never intended to occupy. To rescue the true meaning of radicality requires returning to its roots.

In the 1970s, American surf culture adopted “radical” as a way to describe being “at the limits of control.” Radical meant living at the edge of extreme conditions and exposing yourself to danger that threatened to push you into a blue crush abyss. This idea imagines radicality as a kind of revolution, the moment of total collapse when the board drops out from under your feet and it’s all freefall. Today, most people think the radical is that feeling of riding an exploding wall of water: an exciting rush, a break in the familiar, a rupture that throws everything into potential confusion. Weirdly, this vision of the radical seems to ignore the dimension of time. It is completely tied up with that moment of chaos, and obsesses over the performance of destabilizing the conventional, without appearing to consider its consequences. What comes after the radical moment? Does it lead the way to a better future?

This conception of radicality is hype. It’s a way of whipping up the crowd, of feeding a frenzy of frustration, seduction, and desire. The radical today exploits bored and boring people by letting them feel like rebellious teenagers. Of course, it’s all an illusion: the thrill of being publically naughty and the delight of breaking rules rest on the absence of transgression. It’s all permitted. In fact, the thrill is the selling point. Advertising simply took the surfers’ adrenaline rush and used it to create deranged consumers. Today, the radical is largely meaningless outside marketing strategies and PR spin.

It wasn’t always this way.

Although the word radical comes from the Latin radicalis meaning “to have roots” (hence “radish”), it actually dates to medieval times. The feudal philosophers who invented radical were looking for a way to explain how it can be that time keeps going forward, but nothing seems to really change. They believed that it was impossible to influence fate and that God had created an eternal structure for human society, with the king at the top and the peasants at the bottom. Granted, each generation did seem to drift a little, but sooner or later, the philosophers reasoned, society would always return to its roots. Because medieval reasoning didn’t have the concept of social or technological progress (which was invented during the Renaissance and perfected during the Industrial Revolution) feudalism was ultra stable, and remained basically unchanged for more than 500 years.

The original meaning of radicality is therefore deeply embedded in cycles of time. You only need to get radical when things are generally going badly, when everyone around you has lost the plot, or it’s all totally gone to shit. Radical is the moment when you realize that the only way to go forward is to hit the reset button and start again from the beginning. This is completely opposed to what we normally think of as radical, which is a positive, upbeat, stimulating invention – playful and engaging, and even a little scandalous.

It is the tension between these two types of radicality – the long cycle of returning back to the origin and the short shock of flux – that make fashion such an interesting creative field. As an architect, the time-scale of my own work is so vastly removed that fashion’s paranoid schizophrenia is almost incomprehensible. There isn’t any other industry so invested in instant impact, or so dedicated to such a predictable schedule of production. Imagine if architecture reinvented the future every three months. The logic is as absurd as it is unnecessary. The tension of radicality in fashion is hardly addressed and never resolved: multi-decade recycling of styles can be mentioned, but only as a statement of fact (“the 80s are in right now”). The purpose of the cycle itself is beyond question. Independently of this, the quest for hype is related to a scramble for market share and growth, which results in designers being pressurized to create collections that exist at the very limit of the “experimental” (shocking) and the “wearable” (commercial). All successful brands have highly specific niche markets tied to price points and consumer preferences. From these fiercely defended forts, they attempt to expand into rivals’ territories, with the effect that collections often have to be chameleonic, appearing as many things to many people.

It was precisely the total rejection of ambiguity in JW Anderson’s Spring 2016 womenswear at London Fashion Week that I found so powerful. The collection pared back design to its fundamentals, returning to the core qualities of fashion’s archetypes and recombining them to create something at once obvious in its provenance and unprecedented in its appearance. The collection took clothes with extremely specific functional and socio-political roles and critically reframed them. It explored how femininity is manufactured, at the same time that women are manufacturing their own image. This was fashion as a subversion of gender politics and power: nonworking bra hooks on the outside of a knit blouse, with improbable loops between the cups right at the moment they would normally be under greatest strain; padded brassieres splayed like peacock displays, overt symbols of sexuality now as artificial and overblown as silicon breasts. There were girdles that, rather than constraining the female form to an imagined ideal, projected a sense of feminine sexual domination. Perhaps of lesser importance, there were plays on scale – pockets exaggerated to consume a whole garment, colossal cuffs and muttonleg blouses of equine proportions. Presented under high-intensity lights intended for car showrooms, the room was a fitting metaphor for a show whose clarity practically verged on the didactic.

As a collection, it spoke to me about creating change at the roots of fashion, by challenging social norms from first principles. It was precise and it didn’t court approval, both key characteristics of radicality. JW Anderson pushed the constraints of contemporary fashion to their absolute limit. Admirable though that is, there is always more to be done: globalized supermarket supply chains made seasons a thing of the past, when will international fashion follow? Conversely, what would it mean to present non-gendered collections? Are there restrictions preventing men from modelling in women’s shows and vice versa? Or is it only impossible because it represents commercial suicide? If so, why? Should the artistic production of fashion be beholden to shop floor stock calculations? Or is there a way for designers to reclaim some creative autonomy?

One of the paradoxes of the radical is that the return to the origin is never an end, but a new beginning. As such, it is a boundless sequence, and there are still many points in the deep past with the potential to surface. The world today seems increasingly unstable. From new patterns of work and life to economic insecurity and the difficulty of forming meaningful relationships, we are desperately in need of a radicality that isn’t destabilizing, but restorative.

Carlo Brandelli – Creative Director of Kilgour, London

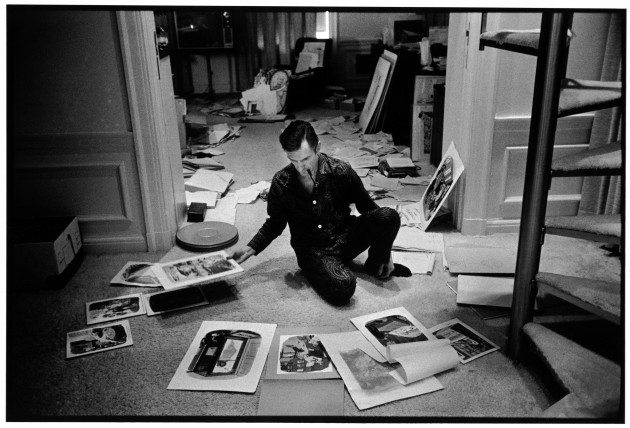

On the 14th of July, I visited Carlo Mollino’s apartment in Turin – the place where he had photographed his now iconic polaroids of hundreds of women. I had been friends with the curator of the Casa Mollino for some time, the very perceptive Fulvio Ferrari, who left me alone in the apartment and, knowing I was a fan, said to me,“Do what you like and take your time.” Of course, I borrowed one of the polaroid cameras in the apartment and took my own polaroids. (It was also irresistible for me to try on one of Mollino’s dressing gowns, which I wore in the apartment for a few minutes.)

I shot two cartridges of film, and the best three images are here. None of the polaroids that I allowed to develop in the apartment came out clearly. Every image was abstract. The only one that was identifiable was of one of his works, an iconic white chair. Another was a shot of the entrance hall, which is a blend of fading cream hues – the colors of Turin, if you know the city. And the last image I took was in his bedroom. There is something abstract in that image too – an unidentifiable visual to the right.

This experience was not radical. In fact, I probably expected it. What is radical is that this type of “connection” is no longer normal in the world in which we live.

Richard Turley – Senior Vice President at MTV, New York

Radical is a comparative term. Culturally, radical is whatever you don’t do – not having a phone, not taking pictures. A reductive opposition to taking part. Consumer, social nihilism. Acerbic cynicism as safety mechanism, inoculating ourselves from pretending to not understand the rules of the game by refusing to take part. Convincing ourselves we’re zigging when others zag. It’s a safe place. Elevating ourselves by undermining the context of our relevance. Dismissing our own influence over ourselves. The most confrontational position isn’t the traditional one. Recent thought has sought to remove the previous apparatus by the most brutal means and to call it radical. Maybe it still is. But up close we are deathly boring creatures. A bunch of sub-robotic robots following each other. Round and Round. Round and Round. We stand for very little anymore whilst successfully convincing ourselves that we pursue higher goals. The reality is those goals are so meager. A better house, a better job, a better pair of shoes, a jumper that fits better, a better phone that lets us share better pictures of better selves.

No one fully understands the implications of the mass-migration of 2015. A radical metadialogue between states. Global news as group chat. Speech bubbles crowding the frame, covering the open wound. The logic of a problem approaching a solution has been successfully delineated. On many levels, it’s not a problem inching toward resolution, it’s a crisis exploding into static, raising old histories and producing new fears. But the sight of families opening their arms to refugees allowed at least the idea that we can be more than a list of consumer products and bucket-listed experiences. The ingestion of many of the world’s oldest races into one of the world’s richest is a huge social, human, political experiment. The exciting thing might not just be that Germany has showed us that Western societies are still capable of acts of generosity – amidst their largely isolationist tenancies. It is the vulnerability that it demonstrates. Vulnerability feels in and of itself oppositional and counter-intuitive, and it will make Germany far stronger for it.

Also: Lullaby by WH Auden.

Ingo Niermann – Writer, New York

MIDDLE-CLASS WARRIORS

For almost 20 years, the Western world had been exposed to Islamist cruelties. The casualties were one thing, they could easily be retaliated with advanced technical warfare. But when it came to being radical, the West had lost its cutting edge.

Of course, you could argue that Islamism is a Western phenomenon as well and that, in the globalized world, the West is everywhere. Still, the West felt amputated. Islamists made a point not to be part of the modern Western world, while in the last 200 years, new radicals had basically always been trying to be even more modern, more Western. And while the West stayed radical only on the screen – in movies and computer games – these people took those aesthetics and made them real.

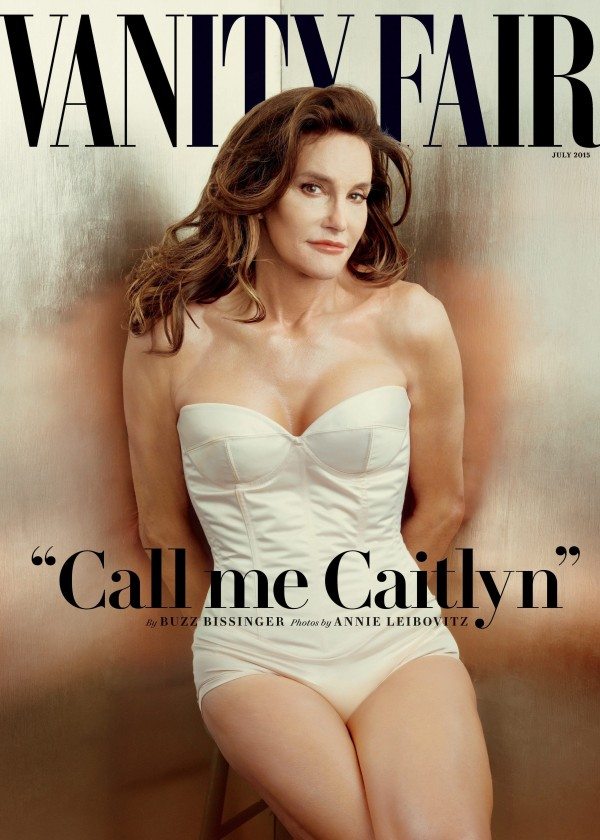

Then, the West struck back. In June 2015, the cover of Vanity Fair announced the transition of Olympic gold medal winner and reality television star Bruce Jenner into Caitlyn. Jenner is a Republican, has been married three times, and is father of six kids. With Caitlyn, gender transition became a mainstream sensation. Here it was again: a romantic radicality of the Western World, and no Islamist would ever be able to adopt it.

What was so spectacular was not just the gender transition – this had already happened many thousands of times. It was Jenner’s age and conservative background. Caitlyn’s transition was proof that you can be radical at any age and not turn into a youth maniac. On the Vanity Fair cover, Jenner appeared as a prototypical well-maintained lady of her age, with big hair and decent cosmetic surgery. German writer Ernst Jünger’s scenario was about to become true: the elderly becoming the new radicals, since they have nothing to lose.

Three months after Caitlyn Jenner’s Vanity Fair cover, another photo took the Western world by storm: the image of Aylan Kurdi, a Kurdish-Syrian three-year-old boy, washed ashore on the Turkish coast. Again, not that we didn’t know about the hundreds of thousands of Middle Eastern refugees before, but this sweet little child with relatives in Canada and a middle-class background felt like an undeniable part of the Western us. And, suddenly, the natural violence of the sea was much more real than the comically exaggerated brutality of ISIS. No, the Western world didn’t feel responsible for how ISIS had turned its own violent games and movies into reality. No, it didn’t feel responsible for killing civilians in Afghanistan and Pakistan with drones. But it felt responsible for the death of a small, innocent child that had hoped for refuge in the West.

It wasn’t just Aylan. Once you mourned his very death, you had to mourn all the other children – all the fathers and mothers, all the people who died and were still supposed to die during their journey to the West. The movement of people who risked their lives to escape ISIS was many times bigger than that of the people who ISIS was able to recruit. For every crazy boy that was executing ISIS hostages, there were thousands of boys – and girls and fathers and mothers – who risked their lives to be part of the Western world. They wanted to be nothing but peaceful, completely normal, middle-class citizens, just as Caitlyn Jenner took hormones every day, did cosmetic surgery, and divorced a third time to live the normal life of an elderly middle-class woman. Different from the ISIS warriors, these unarmed warriors of middle-class normalcy had not been recruited. They came as an unwanted gift. All the Western world had to do was accept them.

In Germany, a large part of the population was quite euphoric about hundreds of thousands of Arabs keen to end up in exactly their country. To welcome them was a chance to outshine Germany’s image as Europe’s grim, if not sadistic, austerity master. Still, Germany was in particular danger of a disastrous repetition of two previous welcomes. First, for the millions of Southern European and Turkish Gastarbeiter (guest workers) who helped to sustain the German Wirtschaftswunder (economic wonder) through the 1960s and early 1970s, and who later on in the 1980s where accused to be a main reason for rocketing unemployment numbers. Second, for the East Germans, and finally for all of East Germany after the end of the Cold War. Euphoria turned into misery, when subsidies for the East went into the trillions. Unemployment in the East nevertheless stayed high, and Germany finally felt forced to start its notorious austerity politics.

Maybe this time it will be different. Maybe the Middle Eastern refugees are the beginning of a revitalizing Völkerwanderung (Migration Period). Maybe the transsexuals will be the avant-garde of a new sexual confidence. But the Western middle class that euphorically welcomes them is, at the same time, rigorously sealing themselves off from people with different wealth, age, education, religion, or ethnic background.

So far, the applause for refugees and transsexuals is very much like augmented virtuality. While augmented reality means to virtually extend the real environment, augmented virtuality is spicing up the virtual with real elements, sustaining a self-perception of the Western middle class as compassionate even though they are no exception to the sociological rule that richness and egoism correlate. This holds true not just for the upper one percent, but as well for the upper five percent, ten percent, 20 percent, etc. There’s already the scenario in place to seal off the refugees and other minorities – and a walled ghetto is not enough. Egyptian billionaire Naguib Sawari intends to buy a Greek island, rename it Aylan Island, and invest up to 200 million dollars to give Arab refugees untested homes and jobs.

But who knows who will end up living in a ghetto: Is it the people on Aylan Island, or the people in the rest of Europe? The more densely populated the world becomes, and the more different regions grow dependent on one another’s supplies of raw materials, merchandise, and capital, the more isolation will become a luxury. Once Aylan island has become a success, more will follow: Transsexual Island, Lazy Island, Vegan Island, IQ 140+ Island, IQ 90- Island, Communism Island, Anarchism Island, Stone Age Island, etc. The Greek archipelago will become the transgressive future of the Western middle class: its diversification into voluntary tribes.

Angela Hill – Co-Director of Idea Books, London

Since March this year, I have been getting up at 4:30am. Before that, I used to get up at 7am. This 2.5 hour shift in my day has had a RADICAL effect. Of course, the first few days of doing this I experienced an exhaustion previously unknown.

Now life is remarkably different. I experience the sun, the air, the night, and “things” in the morning: I breathe and know I am breathing.

I seem to “feel” more.

I have flashbacks to times … of walking aged 12 or 13 through Epping Forest with my father, the perfume “Calendre” from my teenage bedroom and its position on the dressing table, the swing in Hyde Park – these electrical impulses of images long gone are fleeting and come and go uninvited and “unreasoned.”

Play New Order’s “Elegia” and that’s how I feel now. 2.5 hours different, every day.

Also: Pretty in Pink.

Konstantin Grcic – Industrial Designer, Munich/Berlin

Radical is a man named Alex Thomson, a British sailor who competes in solo, non-stop around the world races. His new boat, an 18-meter-long IMOCA 60 Class racing yacht, is made entirely of carbon fiber and outfitted for extreme endurance and high speeds. Radical is the race for which the boat is built: the Vendée Globe. Regarded as the “Everest” of offshore yacht racing, it is the only one of its kind – a 23,000-mile, three-month battle against the elements. Over the last year, I have been working with Alex Thomson and his sponsor Hugo Boss on the branding concept of the new boat.

Michael Rock – Co-Founder of 2×4, New York

Are we not trapped in the very devices we devised? Have we finally reached the apotheosis where there is no more outside, no route of escape? Now, ideology has been replaced by “Brand Values.” Radical has been recast as “Disruption.” Brand and disruption are two sides of our contemporary coin, the currency in a differential system of competing identities. It’s a zero-sum game wherein Apple and Alibaba, Kimye and Kazakhstan all compete. The disputed territory over which campaigns are waged is the dwindling real estate called “Mindshare.” Disruption is a business model that reassigns control (usually in ways that disadvantage the disadvantaged). Entrepreneurs promise to change the world by developing new surfaces on which to paste more advertisements announcing more brand values. Isis has Instagram. Airbnb, Uber, and Spotify consolidate distributed empires: the global’s insatiable appetite for the local. It’s a battle fought on-screen where we, the dazzled spectators, root from our couches, cradling our next-generation PDAs, blurting out clever 140-character encouragements, right up until the point we are forced to live amongst the consequential rubble.

Bjarke Ingels – Architect, Copenhagen

Cali Thornhill DeWitt – Artist, Los Angeles

I think radical is there if you want radical. Anyone who says it isn’t is not taking the time to look around. A short list of radical action and work I’ve seen and thought about in the last couple weeks:

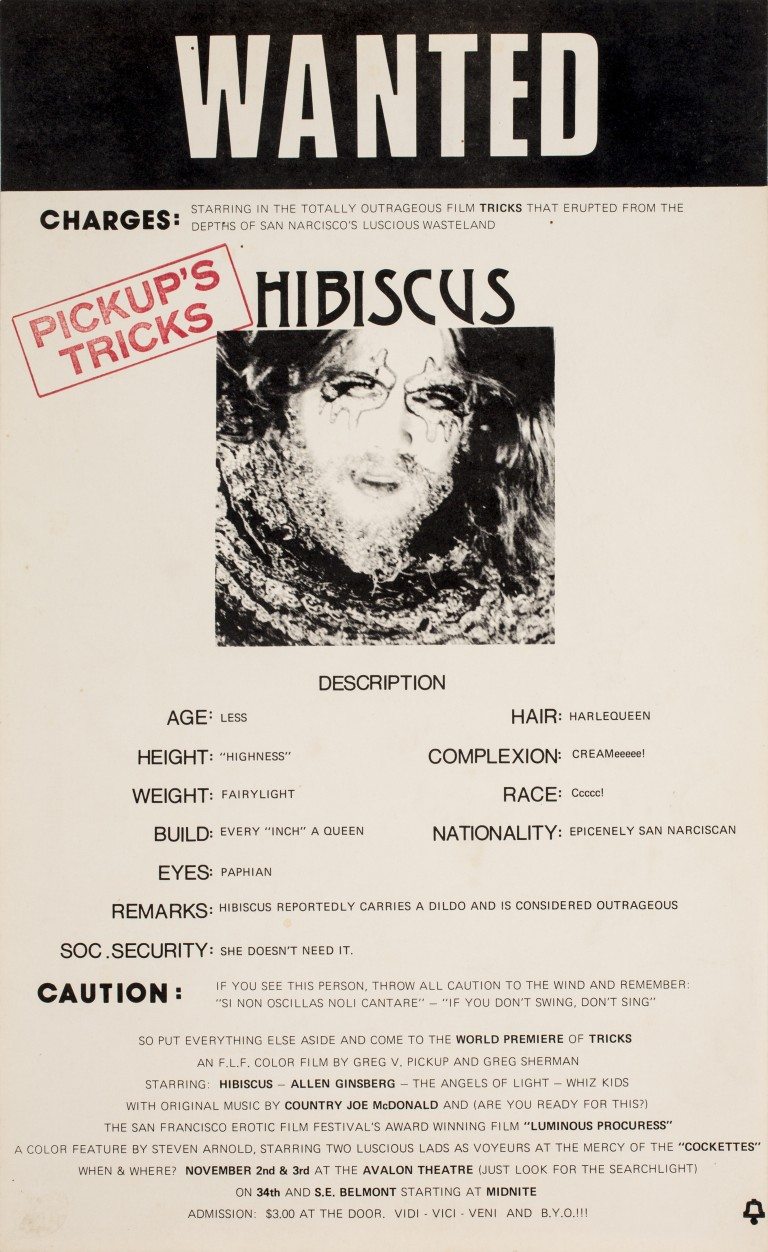

A Night On The Edge Of Forever – new book about “the art of midnight lms, free theater, and the psychedelic underground in San Francisco 1969–73“ published by Wildlife Press.

Billy Childish, and his enormous body of work.

The incredible open editions of Diagonal Press.

Torey Thornton’s personal style.

Brendan Fowler's ELECTION REFORM t-shirts and reading material

SonyA Sombreuil and her Cometees clothing line.

Matt Damhave's exhibit at White Columns.

And I just watched Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore by Mark Leckey for about the 300th time and it’s just as radical and wonderful as the first time. Everything is out there for anybody that wants it.

Johanna Hedva – Artist, Los Angeles

#blackoutday on Tumblr.

No question. The most radical thing right now.

Every day, white supremacy and capitalism collide. When #blackoutday filled my Tumblr dashboard with selfie after selfie of glorious melanin, it was the 21st century’s version of the march on Washington. After centuries of being told otherwise – centuries of being beaten, raped, killed, and oppressed – it needs to be insisted on: black is beautiful, black don’t crack.

I can think of nothing else that comes close to being able to occupy radicality.

Shumon Basar – Writer, Berlin/London

The hardest thing about this question is resisting the temptation to roll my eyes and do something more relevant instead. That in itself would not be very radical either. Let me try.

Firstly, there’s the word, radical: a leftover from another age, one where we believed radical change was possible, or at least, something worth writing and fighting about. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the political right – from neoconservatives to covert fascists – have been more innovative, inventive, cunning, and stealthy than whatever is left of the political Left. The Narkomfin Building in Moscow, designed by Moisei Ginzburg and Ignaty Millinis in 1932, was a Communist manifesto for radical communal living, with residents forced to share key facilities.

The Narkomfin is now a crumbling ruin in Putin’s Russia, a lone corpse on life support, and its radical ideas have been definitively eclipsed by the irrepressible human desire towards personal atomization (read: loft living and gated communities. Everyone else gets slums or refugee camps).

Secondly, what about radical violence? The easy temptation is to nominate the Islamic State. But I refuse to, because that would be dignifying Da’esh with exactly what it wants, which is what we have all given, in particular the media: that is, validation through coverage.

Perhaps if I had encountered true optimism, the kind you can actually touch and take solace from, that would be the most radical thing of all. Alas, I haven’t. But I hope one day we all will.

Mara Delius – Journalist, Berlin

There’s hardly a thinker more in demand than Byung-Chul Han. Born in Seoul, South Korea in 1959, the German philosopher is a man of many guises: a prolific cultural theorist who works on the digitization of life, the fatigue society, and the commodification of love, who manages to spin elegant arguments around Brazilian waxing, Jeff Koons sculptures, and the smooth surface of an iPhone. He is a reluctant poster-boy of the left-leaning critique of transparency and the Internet of Things, an energetic professor with oversubscribed courses on “perspectives on capitalism” and “forms of mysticism,” a respected academic who thinks and writes in beautifully crafted sentences, a reclusive man who hardly travels out of his adopted hometown of Berlin.

I had intended to interview Byung-Chul Han, and although we met and spoke for quite some time, he declined to be quoted. But the following is a play inspired by our encounter:

“The World as Will and Representation” [A play for two.]

The journalist arrives at the location the philosopher had suggested in his email: a very noisy café on Helmholtzplatz, an awkward combination of cute and rough (candles on the table that may or may not be scented, a we-only-use-organic-milk diktat, a local at the bar who looks like Hemingway’s East German brother).

Previously: the journalist had spent hours carefully preparing a good form and flow for the conversation that is about to take place. The journalist had thoughtfully composed a look that’s minimalist-yet-sleek, but not too “put together,” as to minimize the risk of irritating the philosopher.

The philosopher enters. He’s wearing 90s shades (black), boot-cut jeans (black), a shiny shirt (black), and his hair is pulled back into a low bun.

Journalist: Hi, I’m Mara, very nice to meet you!

Philosopher: You are a journalist. Why do you want to meet me?

J: Well, I would like to speak with you about –

P: I tell you what – journalists are all cowards. They are always afraid. Afraid!

P vigorously rolls his eyes, in a “I’m not mad, I’m just wise” kind of way. P bursts into high-pitched laughter. P suddenly stops laughing and embarks on a 25 minute rant. His wild gestures evoke Nabokov’s “Pnin,” Croatian karate movies, and post-ironic Zen. Various subjects seem to upset P – the world, the market, journalists, especially cultural journalists. It’s dawning on J that this is really the worst time to be a journalist sitting in front of this particular philosopher.

P (pulling his disheveled hair back into a bun and pointing at J’s printed interview notes): What is this?

J (sheepishly): Oh, I think what you were just saying about power dynamics is really interesting. I actually wanted to speak with you exactly about this, for a … (J carefully avoids the term “interview”) … conversation that I would like to publish in –

P (shaking his head): Interview? No, no, no! I don’t do interviews. No, not an interview. No!

P shakes his head to the point of head-banging now. J is familiar with this kind of reaction from philosophers, and thinks “We’ll see about this.”

J: Well, I may do a profile piece with some quotes. After all, you’re one of the most interesting philosophers of our time. I’m fascinated by how you approach the digital age.

J throws in a few catchphrases and drops a few names, Luhmann, Deleuze, Schirrmacher.

P (disgusted): The digital? No. I’m no longer interested in that. You’re completely mistaken. I’m working on mysticism now. Journalists! Just out of interest, how much do you make?

An interlude of business-like banter ensues, during which J dutifully answers every conceivable question about her salary range, office situation (open plan or cubicles, what kind of chair, walls glass or concrete, how attendance is monitored), staff size (how many editors, how many stringers, how many freelancers).

P (exasperated): It’s too noisy in here!

P runs out of the café and sits down at a table outside. It’s raining heavily.

P: The digital! This is the wrong approach! You have to start differently – within the structures themselves!

Philosopher: The digital! This is the wrong approach! You have to start differently – within the structures themselves!

Journalist: Fine. Mysticism, then. Let’s talk about your new project.

P jumps up and runs over to the place next door (faux 60s style cocktail-bar meets interior of a camping van with red pleather seating). P sits down outside. J follows.

J: Fine. Mysticism, then. Let’s talk about your new project. You’ve already worked extensively on the notion of the Other. To me it seems to connect your different works.

P: Let’s go inside. Oh, this is a cocktail-bar!

P orders a beer, J ate a that comes in a Scandinavian-looking plastic mug (red).

P: I hear you’ve worked on mood in your thesis?

J sketches a brief outline of her thesis, feeling inadequate.

P (delighted): This is not philosophy!

J (politely annoyed): Well, it wasn’t meant to be.

P smiles. P then embarks on a long, warm, well-informed accolade of J’s academic teachers and invites J to teach a course at his department. P looks out the window. It is still raining.

P (decisive): I’ll leave as soon as it stops!

Ten minutes of detailed, sharp, witty thoughts on transparency, otherness, self-harm, hair, Heidegger, Barthes, and pornography follow.

J: It would be a shame not to print this!

P: No, I’m not doing an interview! I have two sides to myself; sometimes I indulge in the journalistic. But I’m done with this for now. I don’t do interviews anymore.

J: Wait, what about the incredibly informative, theory-laden interview you gave to …

P: That wasn’t an interview. I emailed answers. It was all in writing.

J (putting on on an earnest face): I completely understand. You’re a man of the written word. We can do that, too.

P (laughing hysterically): No, no – I don’t have the time. I now need to spend my time reading, preparing my class on mysticism. I’m reading the Quran and Novalis.

P looks out the window. It hasn’t stopped raining.

P: It has stopped raining!

P is about to run outside.

P: Did you walk over, or did you cycle?

J (sensing that this answer will be the end of the conversation): Nope. I drove, actually.

P (animated): What kind of car do you have? A new car?

J: An old Saab.

P (excited): Saab! I only once had a car – it was a Saab. From the 70s. I can’t drive. I’m such a bad driver, I had to sell the car. I almost crashed it once when I was trying to find a beer can under the seat. Some people actually just can’t drive. A Saab! May I see it?

For the past 45 minutes, J has been regretting that she won’t be able to use any of this. J is now basically dying.

P and J go outside and walk to the car. It’s still raining.

P (stops in front of the car): What a beautiful form … It doesn’t have an airbag. But you’ve got a bunch of flowers on the backseat … Be in touch!

P disappears into the rain.

Virgil Abloh – Creative Director of Off-White, Chicago

To me, radical is by design against the grain with a particular sense of advancement.

The against-the-status-quo is the easy part. The particular-sense-of-advancement portion is subjective but ideally has a resonating effect on culture afterwards. Radical things become the new reference points.

In the last six months, a number of things have struck me as radical:

Drake’s album cover for If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late.

The film Ex Machina.

Kanye West’s Brit Awards performance.

The Supreme skate film Cherry.

Kate Cooper – Artist, London

I’ve just finished reading Pornotopia by Paul B. Preciado, which takes the empire and brand of Playboy and considers what this means for the production of gendered space, particularly the idea of architectural space—the members club, the bachelor pad, all as spaces for the production of the autonomous straight male sexuality. It’s interesting to think how Playboy successfully managed to re-insert a feminist idea of making the domestic space gender-equal and packaged it as the ultimate male utopian dream. It’s as if the wages for housework idea was hijacked, and this playboy character had already set up his bachelor pad, free from any of the constraints of family life. Preciado presents the Playboy man as the double agent, the spy, these spaces being performed for these straight male stereotypes: the knock-off James Bond, or even worse, the modernist architect.

In an earlier book, Testo Junkie, Preciado became their own lab rat. Then known as Beatriz, she wrote the book whilst taking illegal testosterone supplements. “I am a copyleft biopolitical agent that considers sex hormones free and open biocodes, whose use shouldn’t be regulated by the State commandeered by pharmaceutical companies,” she claimed. Part polemic philosophical mediation, part memoir, part biological experiment, it’s the ultimate guide to the personal as the political. She presents the body as something implicitly owned by the state – this idea of “pharmaco-pornographic capitalism,” the new regime of the production of sexual subjectivity.

I was reading the book before I started working on an exhibition for Kunst Werke in Berlin last year. Preciado talks about the history of the birth control pill, mapping it to functions of power. Also, I realized that Shearling – the commissioners of the prize I had won – were one of the few companies developing the male conceptive pill.

What I loved most about the text is this link between the performance of the body as an object, as pure image, and something downloaded, distributed, and re-imagined on Preciado’s own terms. More than anything, I loved the way the text made me imagine that perhaps one day I could take a pill and for a few hours, days, weeks, fully understand what it is like to feel male. Maybe in the future we can try on these genders like trying on emotions, the ultimate form of drag.

Thomas Scheibitz – Artist, Berlin

At first thought, few things appear radical. Taken phonetically, chemical compounds called “free radicals” sound perhaps even more radical. Free radicals are highly unstable and have interesting reactive points with unpaired elements. Suddenly, two unpaired and extreme statements of image and sound suddenly come to mind. And taken in combination, they are even more radical.

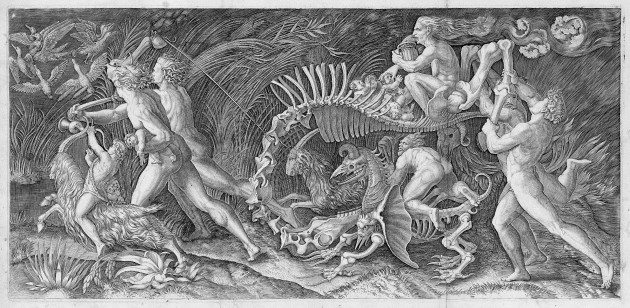

The first is an engraving dated from 1520–27. The authorship is unclear. A pupil of Raphael, Giulio Romano, or even Michaelangelo, is suspected as its creator or inspirer. Equally puzzling is the real intention behind it, or what is actually portrayed. Unusual for its time, it is a radical display of iconography, mythology, and superstitious circumstances. It is radical because it was seemingly created for no apparent reason, in a time when everything representative needed to have a coherent justification.

In parallel, what springs to mind at the same time, is the song from Scott Walker “You Don’t Bump His Head” from the album Bisch Bosh (2012). The recited line “While plucking feathers, From a swan song” intensifies that extreme moment when you can take in music and an image in the same instant. The monotone, uncategorizable music amplifies the mannered delivery of the lyrics. For all its radicality, its appeal is timeless.