VIRGIL ABLOH Plots Chicago’s Second Bauhaus

|Robert Grunenberg

Virgil Abloh, the American mastermind behind the Milan-based streetwear brand Off-White, launched his first furniture line during Art Basel Miami. Abloh’s installation piece of contemporary interior picks up on his formative years as an architecture student in Chicago. Remixing the legacy of the German-turned-Chicagoan Mies van der Rohe, he realized a home capsule that blurs the merits of modernist architecture with contemporary lifestyle mechanics.

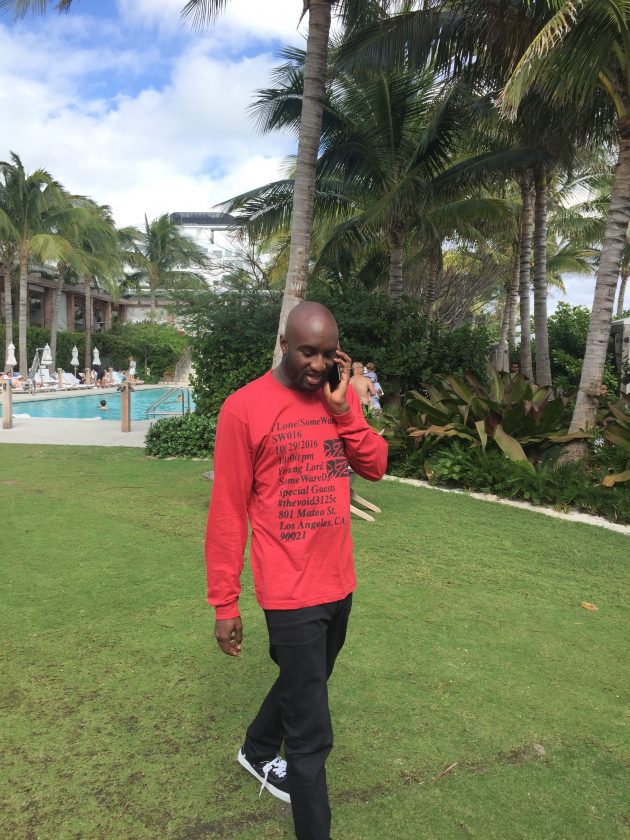

Robert Grunenberg met up with Abloh in Miami Beach to discuss his design ethos, his friendship with Kanye West, and a future project that digs into club culture.

Robert Grunenberg: You have a degree in architecture. I guess everyone who studies architecture dreams of one specific space or house they want to realize. What is yours?

Virgil Abloh: The architecture side of my brain is the backbone for all creative projects I do. I have always taken that skill set and applied it to things that I was interested in. I have an engineering background from the University of Wisconsin and studied architecture at the Illinois Institute of Chicago under the Mies van der Rohe curriculum at Crown Hall, a space that he designed. My focus there was tall buildings. I guess this interested me because of the many skyscrapers in Chicago. I took that influence and thought: If I could design a complex house like a skyscraper, then I could design all kinds of objects, something small like a spoon.

Your dream building was not a house, but rather a structure or system that goes beyond architecture …

Yeah, ironically. My dream house then became a construct, something that you can see in my brand Off-White, and right now it manifests in the furniture piece that I’m showing for the first time at Design Miami. It is my ideal project. It fits into a small space and communicates a larger idea – my design ethos in a nutshell. It is a distillation of who I am as an artist.

How does that express itself?

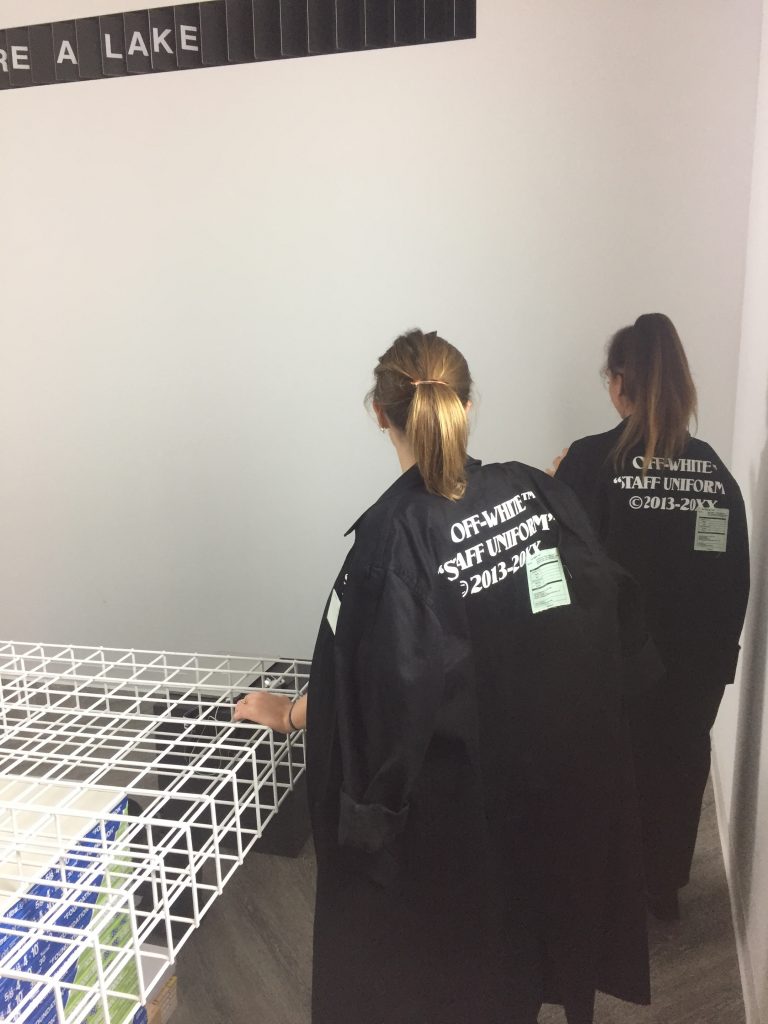

It’s a way of thinking, a contemporary vocabulary that draws on modernist ideas. There are three major things: There is a sign with phrases, which I call a “painting,” then there is a table made out of a grid, a pile of stones, and a stack of sheetrock, and there are cubic sponge chairs. The same ones that I use at my fashion shows.

How do you see people using a piece like that?

It’s not a furniture piece to sit or eat on in a traditional way. It is for something else, and you need to figure out how to use it. I can see this type of work in gallery settings, not in a retail setting per se. People will actually be able to purchase it through a gallery.

How would you describe that x-factor in your design?

My idea of furniture is abstract. It is an interior piece and it is not. It’s not a typical functional a + b = c object. There is abstract dimension to it that can be inspiring. Looking at this table will bring you ideas that you would probably not have when looking at a normal furniture piece. I guess the x-factor is something that blurs the line between function and form.

The text elements on your piece remind me of Jenny Holzer’s installations, the pile of stones are reminiscent of Robert Smithson’s land art project “Spiral Jetty,” and the white grid references Sol LeWitt cubes. All of them tackle infrastructures and systems that determine how we perceive our lived environment.

Exactly. Generally spoken it’s a crystallization of my design career and representative of the time we live in, a present full of overindulgence: more objects, more branding. For me, it expresses the questions: Do we need another brand? Do we need another chair? What is a table through this filter?

Looking at American modern architects like Mies van der Rohe or Frank Lloyd Wright and the modernist discourse, there was always a connection to society and utopian ideas, a proposal of what society could be like.

The idea of modernism has a strong influence on my work – the global aspect of design in a built form. How can you create something that unlocks the interest of a generation, that feels contemporary and yet pushes the envelope a bit further. I am doing this to show the next step of what design can be: clothing, products, furniture, and artistic expression. Design as a guide for today’s generation in America and for a global point of view.

I saw you DJ at Kid Cudi’s event here in Miami. What is your interest in club culture and how is that connected to the design utopia called “Haçienda”?

That’s another piece that I show here in Miami – a project called “Haçienda.” It is a collaboration with the British architect Ben Kelly. He designed an influential club from the 1980s called Fac 51 Haçienda in Manchester, UK. Him and me commissioned a mobile night club. It can be transferred around the world and exist in different spaces. It deals with club culture and how it influences our lives. We want to celebrate it with a mobile club, activate it by different DJs, and have it experienced by many different people.

Why did you choose Miami as a place to present your furniture?

Art Basel Miami is one of those few times in the year where every kind of culture and art can merge. There is the main fair with a specific crowd, but the events around Basel also attract people from outside the art world. It’s a unique and a mad time to crash different worlds. The schedule, the events, and the energy is nuts.

Many of your projects are collaborations. What do you like about working as a collective?

I create in an open-source-kind-of-way that shows the process of how things are made. The work and the way I communicate it, is inclusive and not exclusive. My circle of friends make up the project. It is a collective of genuine friendship. My ideas are formed by my conversations – people like the stylist Stevie Dance or the photographer Fabien Montique. We bounce ideas off each other. They help me intellectualize my projects and bring in a lot of contemporary thought. We put a lot of energy into thinking and exchanging together.

Who are you particularly thankful to?

Kanye West. He is the figurehead of being an artist in a contemporary culture.

After you worked with Kanye as a creative director for many years, you created your brand Off-White in 2014. I was wondering if there is a political dimension to the brand name?

Of course “Off-White” is done by choice. It is provocative and not provocative at all. It’s just a word, just a color, depending on how you read it. I like the fact that colors can be commoditized. It’s the same thing with my DJ name “Flat White.” With the different projects I do, I draw on different colors. I like to play around with these juxtapositions, blurring the lines between black and white, underground versus luxury, male versus female. I want my brand to be contemporary, a crystallization of the present, not a sleepy brand. I believe culture is something active, what we make of it, what we add to the pot.

What is your idea of streetwear?

Streetwear is a kind of thinking, a genre of art. When you look at brands like Supreme, their ability to translate contemporary culture and art direct the feeling of our time. I am adding to that with my projects in a design space.

How do you find this sense of freedom and boldness to move between so many projects?

I think it is confidence that comes from independence – maybe something you learn in a life as an artist. Everyone has the responsibility to foster in each one of us this desire to contribute to the world. I guess it steers from my background in street culture: I come from a larger community of kids. So I know that youth culture and kids need to see someone that they can look up to. I want to communicate what I have learned. For instance, I am using Instagram not only to inform, but to get people involved. I believe in open source: invite a younger community to my fashion shows, do events that are open to the public. It is important to me to reach those kids, so they understand what they can do to unlock their potential.

Credits

- Interview: Robert Grunenberg