UNPROFESSIONAL. INTIMATE. A LITTLE BIT LIKE A READYMADE.

|Richard Turley & Lucas Mascatello

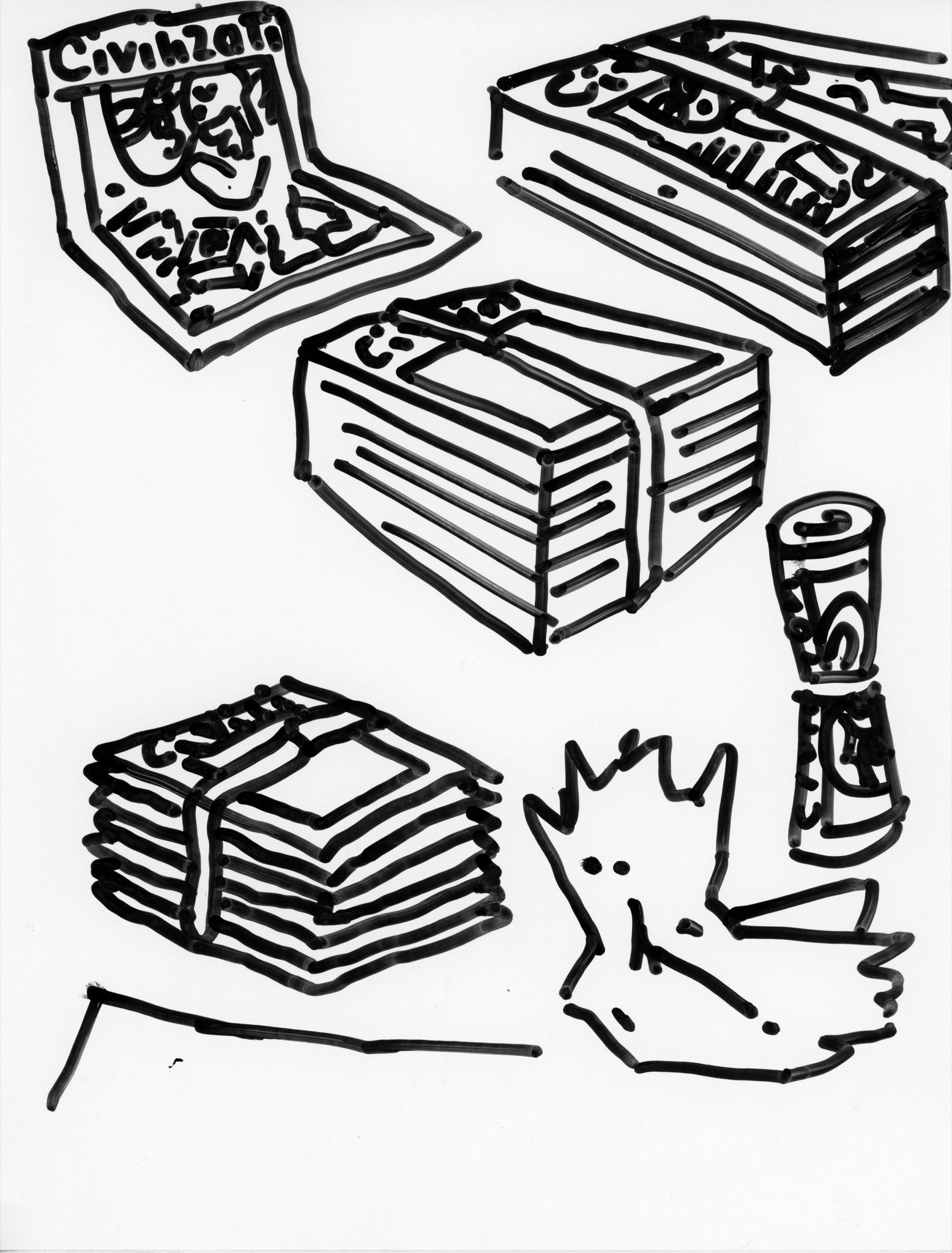

Created and edited by Richard Turley and Lucas Mascatello, CIVILIZATION newspaper is impossible to excerpt – at least in a way that is properly representative of the New York City broadsheet, now in its third edition.

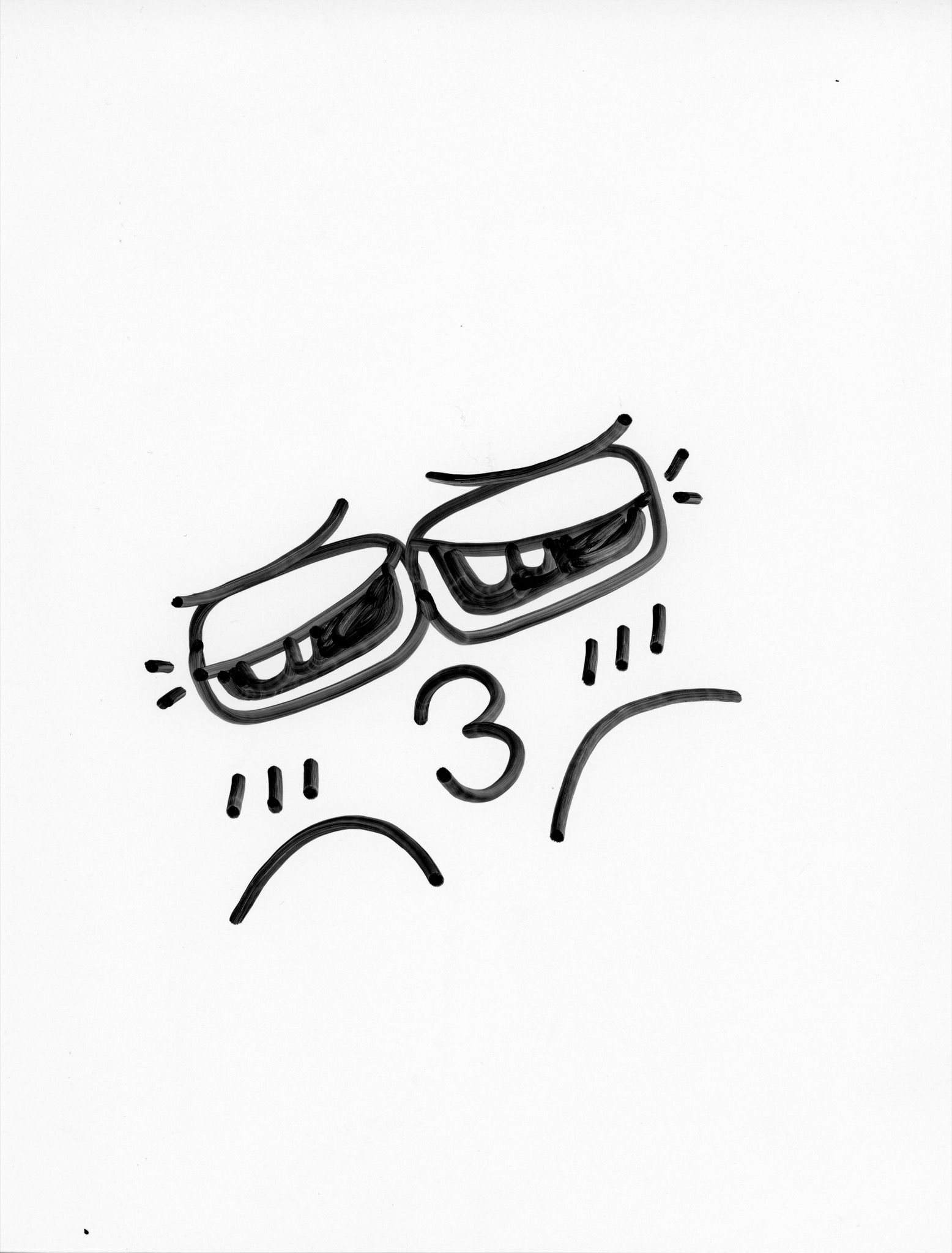

Its pages are so packed with unfiltered conversations, personal logs, and marginalia that the text deforms the columns, punctuated with illustrations, infographics, and often unreasonably small photographs that add to a diaristic, unstable energy. “It reads like it feels to live in New York City,” as one former contributor put it: there’s not enough room for you to control your experience, and you are forced to hear your neighbors fucking. The result, in our view, is a kind of intimacy, sometimes indifferent, at others compulsive; rarely friendly, but somehow incredibly open, even promiscuous. (Civilization does get around: reproductions of its pages were a leitmotif on Junya Watanabe’s Spring 2020 menswear runway.) We asked Mascatello, who one might say exposes himself in his writings for the latest edition, if the question of intimacy was deliberately posed in the project, or rather a collateral theme. He spoke to Turley about it, and their inconclusive conversation on the topic follows below alongside illustrations by Kurt Woerpel, whose moody, Converse-wearing daemon functions as Civilization’s anxious mascot.

Lucas: Hey.

Richard: You hear me? Can you hear me? Yeah, I can hear you. Oh, no I can’t now. I can’t hear you. Okay, you’re breaking up.

You can’t hear me?

I can hear you now. I can hear you now.

Oh, you can hear me now?

Yeah, I can hear you now. Stay there. Whatever you’re doing, stop doing that.

Standing very still.

All right, good. You all right?

Yeah, I’m good. How are you doing?

I’m a bit tired, I mean, honestly. But otherwise I’m all right. Where are you? Martha’s Vineyard?

Mm-hmm.

That sounds nice. Is it nice?

It’s really nice. It’s really, really nice.

Okay, good. Well let’s not interrupt too much of your time away. What are we doing exactly?

Yeah. I mean, I think they want to give them some sort of quote about intimacy in the project. Does that sound right?

Yeah. Any ideas?

I mean, it’s this funny thing where I think it would have been more of a trust exercise if I had thought more about the potential consequences of sharing so many things.

Well maybe it’s more you, Lucas, because I don’t I really feel very revealed. I mean, you have more risk.

Yeah. I think really the project in a way is as open as we can be with each other. Because beyond that it’s, as you said, sort of anonymous to people.

Is it that intimate really? I suppose it depends on how you want to think about intimacy. I mean, if you think intimacy is about being truthful and revealing and unguarded, then I suppose it’s intimate. But in some ways I would almost say that it’s unintimate because it’s just stripping it down. I don’t know if I’d say it’s necessarily the opposite of intimate. But there isn’t much intimacy in doing this. It’s just me on the phone or you on the phone with someone else. Do you know what I mean? The reality is that that’s sort of how it usually pans out in many ways, isn’t it? Occasionally we meet people. But then that’s not intimacy, is it? It’s more like snooping.

I think part of it is we reveal a lot of information, but there’s not a lot of listening involved. That’s half of what intimacy is in a way, right? People don’t really have any way of sharing stuff with us.

It’s nice to hear the insects in the background.

It’s cool, right?

It’s very nice. That’s intimate. That feels intimate.

I mean, there is definitely a voyeurism and an interest in other people’s lives.

Yeah. I suppose also where I get that maybe there’s intimacy is where both you and I have just experienced it … to be honest about it, just the fact that we both are not professional journalists has meant that the divide between journalist, if you like, is crossed over. We’ve really exploited that.

It’s like if professionalism is about having certain boundaries, then us being deliberately unprofessional creates all these inopportune forms of intimacy that are maybe inappropriate sometimes.

Totally inappropriate, I think, many times. Well, at least in two specific instances of being inappropriate.

That’s definitely true.

I suppose that’s revealing more than it is intimate.

Well, I mean it’s funny because for instance, when I started talking to [XXXX], she had read parts of the paper and therefore knew a lot more about me than I did about her.

Well, then that’s it, is it? That’s not intimate, though.

Well, in a way people have social channels that are designed for a certain kind of intimacy, which has systemically become less intimate. If you create a new channel, like a blog or a journal or a diary, then it traffics in some of those conventions. But there’s also no real appropriate model of reciprocity for it. I think that’s part of it. In a way, you made [the iPhone app for sharing collages] Dogma, which is sort of like what Civilization is. A standalone profile, and the network thing doesn’t really exist.

I mean, it’s funny. I’d never thought of those things in those ways, really. I think both Dogma and Civilization are definitely journalistic – as in, journal. As in diary. But they’re also about whether that’s meaningless.

I think part of it is also that social media and society have something to do with the public square and having conversations and shared spaces. This project is a bit more running out into that space and shouting something out then running away. It’s definitely a public statement, but there’s no conversation really.

But it’s fun, honestly.

The anonymous part of it, I think, is a bit like running away from things.

Well the instinct originally to do that, though, was about removing context, wasn’t it? It was about how everything you see or a lot of the things that you read through the lens of social media, whoever has posted these things, comes with baggage, and it’s filtered through how you receive it. It frames the way that you receive that content. I think that with the paper, if you just don’t have any context for things, if you’re not being forced to sort of stare at the person whose words are coming out, then it just becomes a lot more imaginative and information comes at you in a different way.

A little bit like a readymade. People can opt in, I think, too. There’s a sense that some of the things are written so generally and so ambiguously that it’s like you, the person reading it, could have written this, you know what I mean? It’s not even particularly insightful sometimes. It’s just sort of thoughts that a lot of people have.

It’s not trying to be professional, is it? It’s trying to be the opposite of that, really.

Yeah. I guess there’s a thing that happens with platforms. People always professionalize them, ultimately. With newspapers and print media, that happened a really long time ago. Like a conventional media that’s establishment is very legible. I think as social media moves more toward professionalism, it’s becoming the same thing.

That’s really interesting.

I just finished writing this thing for [BRAND NAME] about their fucking Instagram, basically telling them that more people will click it than will read magazines, so why not try to make it as good as the magazine? I was doing this rebrand and talking to them about social media, and it’s like more people see this profile than would read the average magazine, right? Why not try and make the profile or the Instagram as interesting as a magazine might be? But that’s also a form of professionalization, right?

I really like the thought of de-professionalizing the media. That’s really nice. Again, I don’t really know if it’s intimate. But then…

Credits

- Illustrations: Kurt Woerpel

- Text: Richard Turley & Lucas Mascatello