OUT, NOW: Digital Content Princes Take the Helm at the Original LGBTQ Glossy

|Victoria Camblin

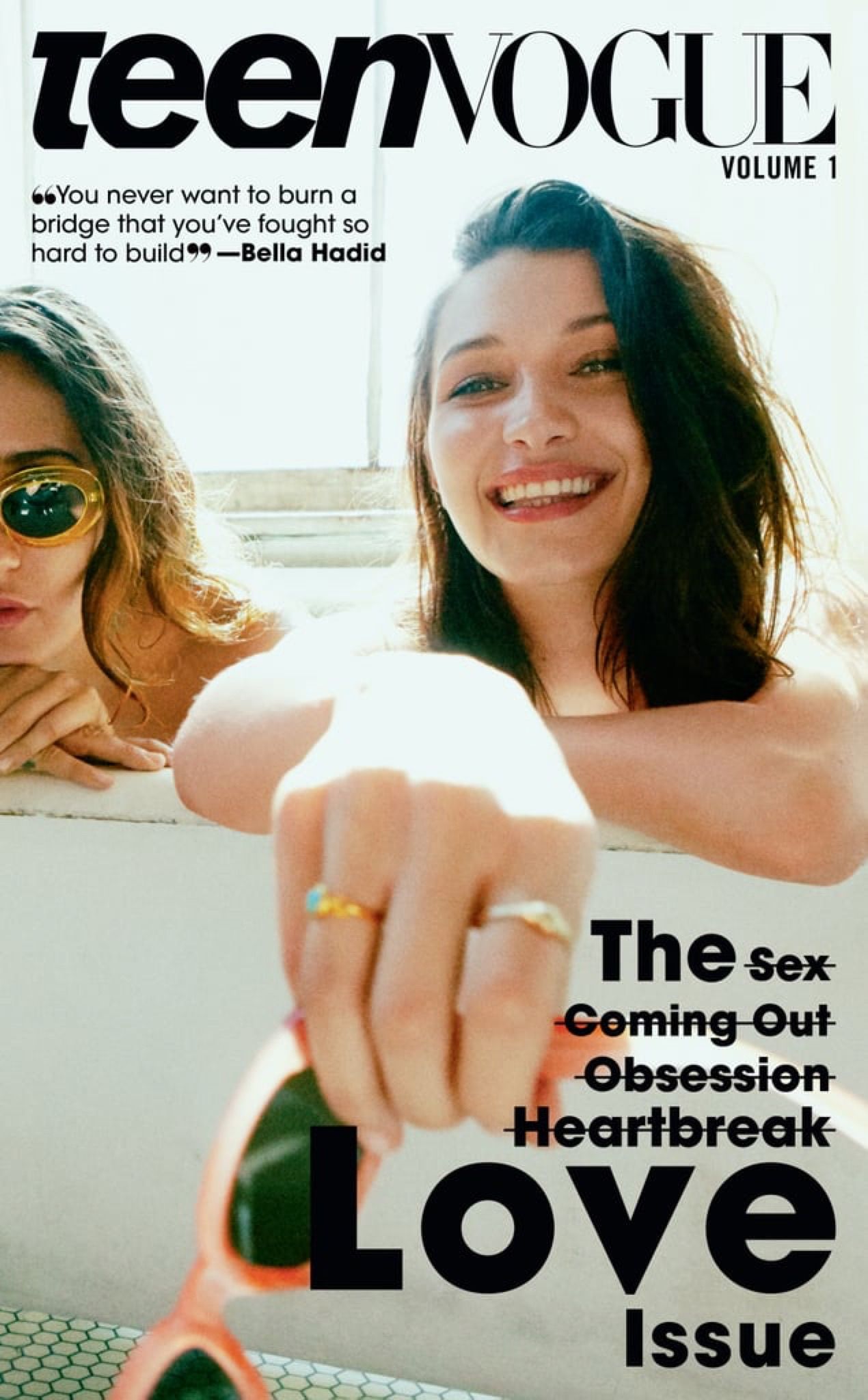

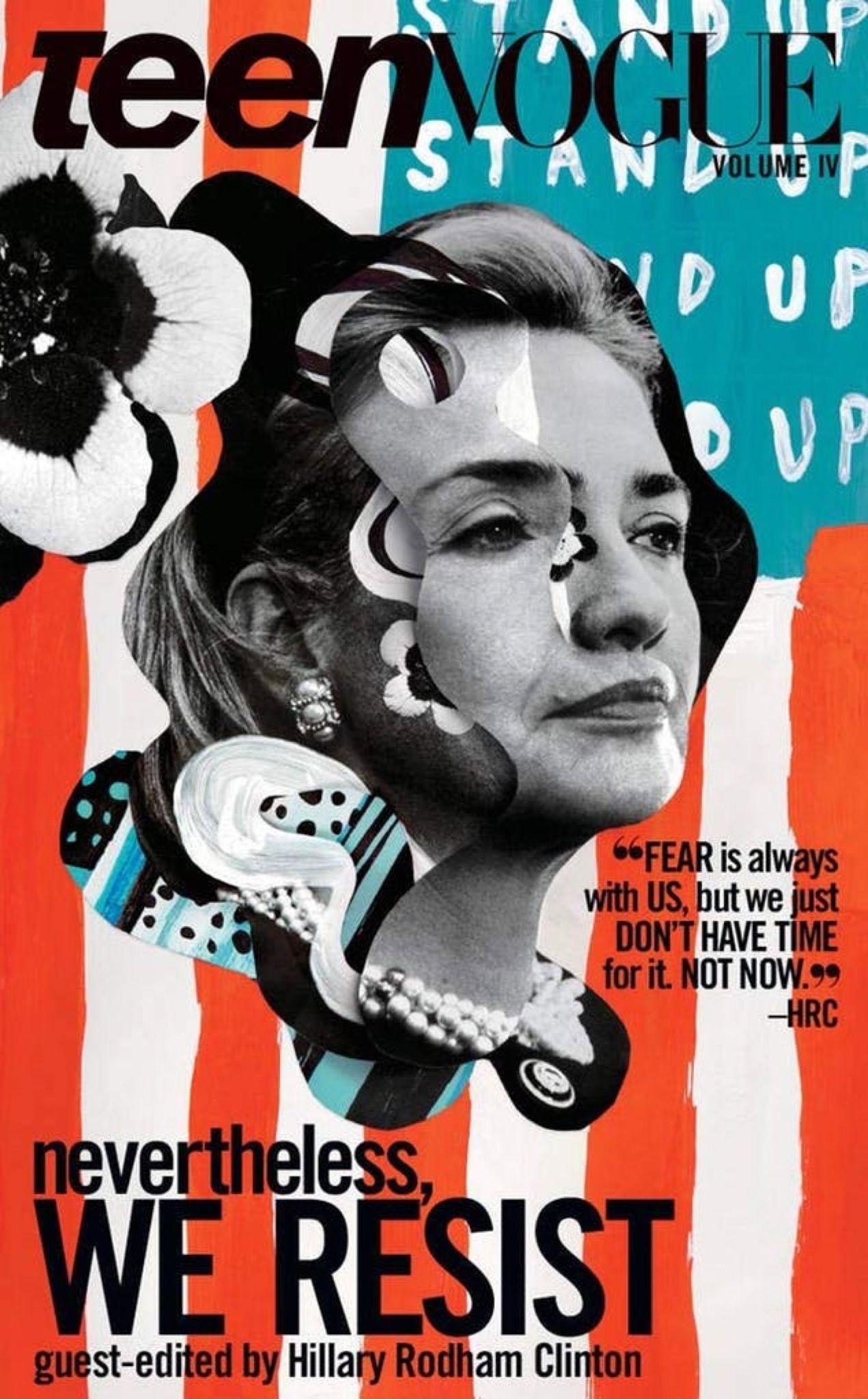

In May 2018, Teen Vogue published an article by sex educator Gigi Engle called “Anal Sex: What You Need to Know.” Controversy ensued. Feminist and Christian right contingents alike took issue with the piece, with one conservative staging a public burning of the magazine – even though the article had appeared online only, and the publication had already moved away from print, and toward a digital- and social-first strategy.

At the editorial helm at the time was the now 27 year-old Phillip Picardi, who began his tenure at Condé Nast as an editorial intern in the beauty department at Teen Vogue, and concluded it as chief content officer for the same publication, having ascended the ranks in only a few short years. Picardi was part of the team known for bringing political and social discourse to Vogue’s historically demure little sister – and for swiftly growing the title’s digital audience from 2 to 12 million daily unique views in the process.

Teen Vogue’s discursive renaissance didn’t save its print version from the chopping block, but it did open up Condé Nast’s remit: not long after the “Anal Sex” scandal, Picardi launched them, the media giant’s first LGBTQ-focused platform. And not long after that, he left Condé Nast entirely, for an editor-in-chief position at the original LGBTQ community glossy: Out, founded in 1992.

Picardi inherits not only Out’s influential queer legacy, but its history of controversy. Lesbian readers have taken issue with its focus on gay men over the years, for example, and recently, a substantial group of contributors has publicly denounced Pride Media, the company that oversees the magazine and reportedly neglected to pay them. These are less than ideal circumstances in which to join a title that should be synonymous with advocacy and representation, but Picardi is seeking cohesion amid the disconnect. “For all of us — these past and present regimes — we can be aligned in saying it’s vitally important that Out exists on newsstands and on a website,” he told The New York Times this week. “And that Out stands by queer creators and stands by them being paid for their work.”

When I saw Picardi’s first issue of Out drop last month – completely redesigned, queer Hollywoodians Hari Nef and Tommy Dorfman tenderly posed on the cover – I reached out thinking we might overlap in Paris during menswear. We did – specifically, for a 40-minute Uber ride between the Palais de Tokyo and the Yohji Yamamoto show across town in the Marais. Picardi was accompanied by Out’s new Fashion Director, Yashua Simmons, whose experience at Hearst Communications made him fluent in both high and high street fashion, and an apt choice to raise the magazine’s style profile. It was the first men’s Paris Fashion Week for both Simmons and Picardi – “We didn’t have the money,” Picardi said of Teen Vogue – so when I spoke to the two digital natives it was in the context of a very material world. In the spirit of my ongoing fascination, and 032c’s, with conversations between editors, I asked Picardi and Simmons about their editorial philosophies and fears ahead of their March issue, devoted to women and non-binary femmes and due to hit newsstands any minute now. “March is going to be wild,” they promised.

Let’s start with how you got here. Philip you had stints at Refinery 29 and elsewhere but were primarily at Teen Vogue and them, both Condé Nast publications. Yashua, you were at the other mass media conglomerate, Hearst Communications.

YS: Interestingly enough, I was with Hearst for nine years. I did eight years at Elle, and then for the past year I was the style editor for the Hearst Fashion Group. What Hearst did was they combined their fashion departments for all of the lifestyle magazines. I was kind of a leader in that department. It was an interesting thing that they did, and it was a good muscle that I got to massage and work out and flex.

Like in a business sense?

YS: Well business, but also from a fashion perspective. I was doing Cosmo. I was doing HarpersBazaar.com. I was doing Esquire.com. I was doing Women’s Health, Women’s Day. You had this shopping group where nothing could be over $100, and then you had luxury, and then you had to appeal to this person in the middle of America, who doesn’t care about a high-waisted jean. So this sort of styling muscle in my head had to adapt to a lot of different things. I did it for about nine months and then Phillip here saved me. But it was a really interesting experience.

Phillip, was there any crossover like that at Condé Nast? In terms of distribution of resources, partners, targets?

PP: Teen Vogue was always like a baby brand. What was wild was that because it was Vogue, the brands we were working with were often Vogue brands. A lot of the brands who wanted credits in Teen Vogue or who we advertised were luxury, but our budgets were small. I’ve always worked with really small budgets my whole career. I didn’t realize that it would become such a necessary skill. I always thought that I’d graduate to the bigger brands eventually.

That’s the thing about budgets: you get really good at working a budget because you have to, and then no one will ever give you what you need because you’ve become a miracle-worker.

PP: That’s totally right.

So at some point there was obviously a change in philosophy at Teen Vogue, and I wonder how that fits in with the narrative of your departure from Condé Nast.

PP: The story with me at Teen Vogue is that I started in the beauty department. I was a beauty intern for Eva Chen, and then I wanted to be the beauty assistant. I didn’t get the job. I ended up as a beauty editor at this very small start-up started by Emanuele Della Valle called Lifestyle Mirror. So I was running my own vertical. I was writing five to seven stories a day. I was the only one – we had no freelance budget, so I had to produce all the content by myself. Then [former Teen Vogue beauty and health editor] Elaine Welteroth hired me to be her assistant editor, which basically was a glorified assistant role, but I was happy to take it because I was so happy to be back at Teen Vogue. I was six months in, [former Teen Vogue Editor-in-Chief] Amy Astley was like, “No, he needs to be promoted to digital beauty editor.” So I did the digital side and I was back to basically blogging for a while.

It’s interesting how much of the editorial firepower there came up through beauty. Yashua, do you also have a beauty background?

YS: No. But interestingly enough – and Phil hates this – I’m one of the very few men who was featured on Into the Gloss! [Laughter]

This beauty vector is interesting, though. Like as a business model, these are relatively accessible products that have a very intimate connection to editorial – beauty products parlay into content, and vice versa, right? Into the Gloss is an online beauty magazine that got into products with Glossier. The 032c model is definitely unique – with our apparel and RTW brands expanding from the magazine – but Into the Gloss did start a strong beauty brand only slightly removed from the editorial platform.

YS: It’s a great model.

PP: No one else has done that in apparel very well, which is interesting.

So you have a commercial advantage with beauty, potentially, you have a broad audience – and you also have a critical access point to sexual and identity politics?

PP: I went to Refinery 29 briefly and I worked for this editorial director named Mikki Halpin who was responsible for a lot of the major editorial shifts there towards news and politics. She took an interest in me, and every time I would meet with her, she was like, “What can we do to scratch below the surface of everything that’s happening in beauty?” Because it’s such a superficial world, and someone bought and paid for it. I started doing stories about cultural appropriation, I started covering more trends and phenomena, writing more personal essays, and all that was being workshopped by Mikki. And then when Teen Vogue called just six months after I got my Refinery29 job, Amy Astley wanted me to kind of audition for the role of digital editorial director. So in two years I had gone from someone’s assistant to someone’s peer, and it was scary because I was 23.

And you’re not talking about a tiny platform either.

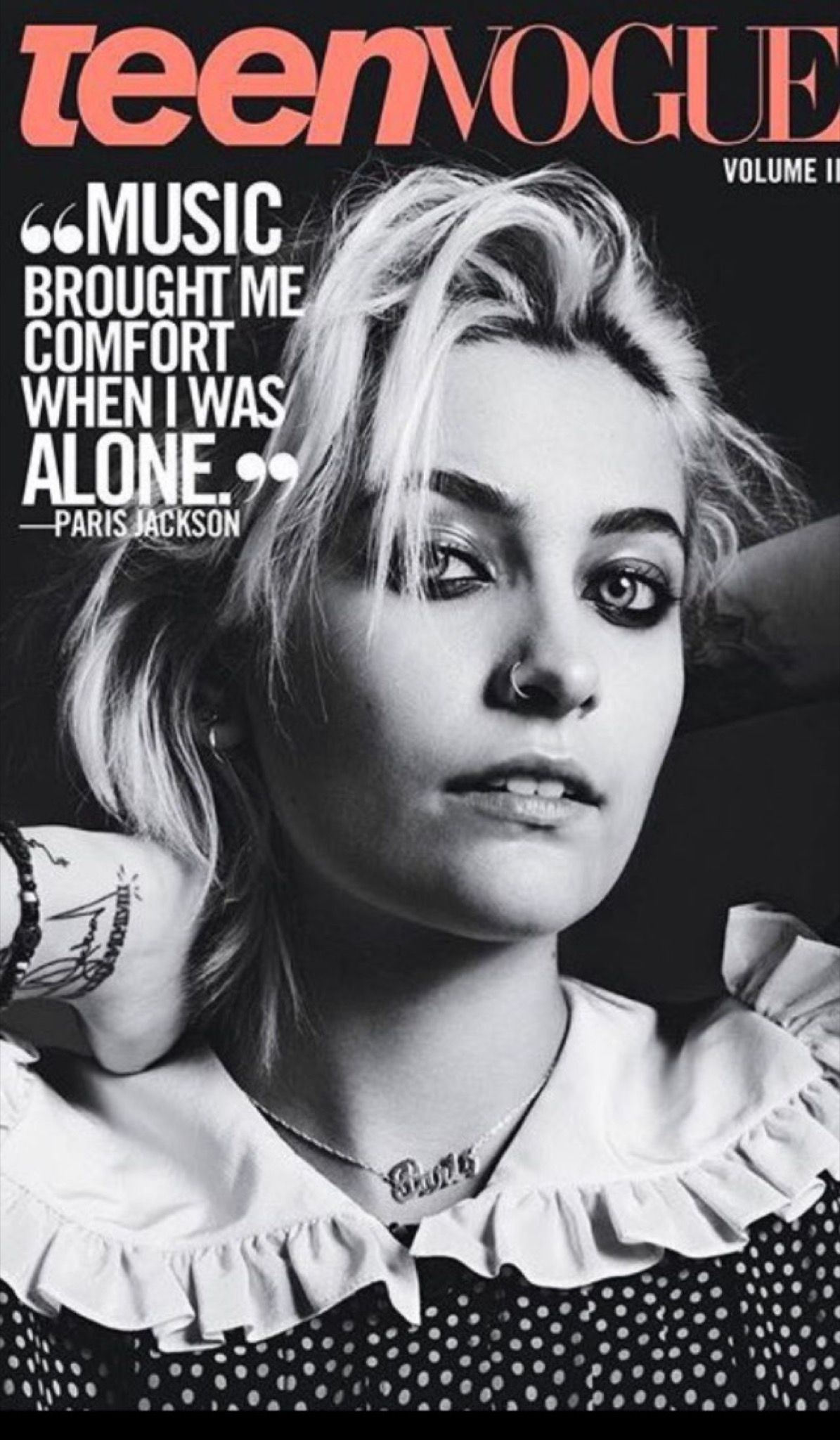

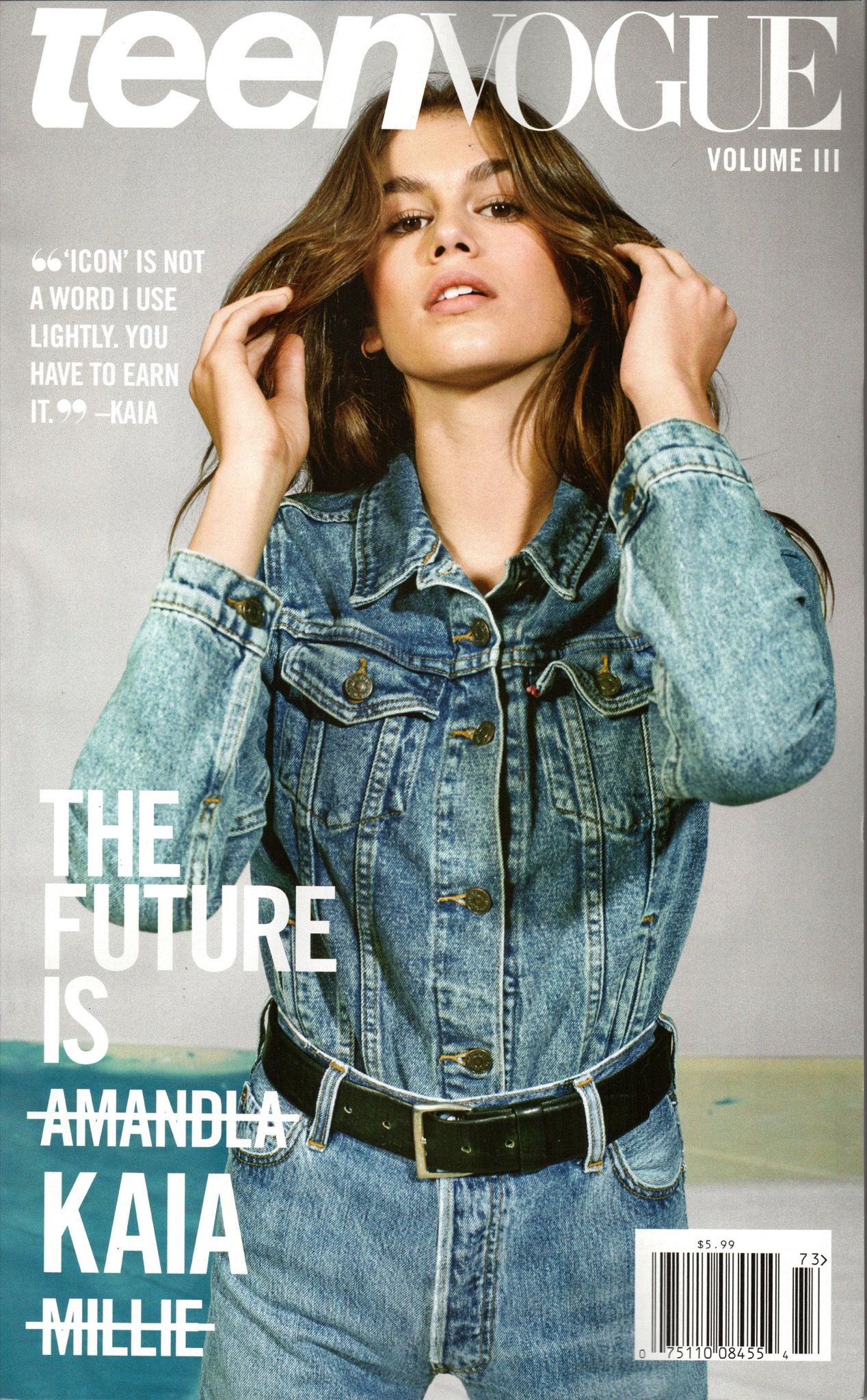

PP: At the time it was so small for digital, but Teen Vogue had a massive social following. And if your website isn’t attracting the same audience as your social, it means that there’s a disconnect between what your followers want and expect from you and what you’re actually giving them. By covering all of this high-fashion runway stuff and sticking into this Vogue territory, we were actually hindering ourselves. It was my thesis that if we covered politics and wellness, taught girls about themselves, showed girls different role models, covered some sports, we could see how our audience responds and get a better grasp of who they are. That ended up being what Teen Vogue became known for.

Now you’re both at the queer heritage brand: Out. I’m old enough to remember when it first came out. I was in San Francisco, I was a kid, and it was on all the newsstands next to the feminist Ms. magazine and it felt like a really big deal.

PP: Ms.!

You know? And in certain periods it did feel like the counterpoint to that – an evolved perspective, but a man’s magazine, too. Obviously you’re approaching it from a less binary position. How is that transition going?

PP: I would qualify this by saying that the Out editorial model initially was that there had to be two editors, one man and one woman. So I think that what we’re doing right now is closer to what Out was initially intended to be when it first came out. The pivot towards it becoming a gay men’s magazine happened in the aughts, when marriage equality was the topic. The publisher and editor in chief at the time decided it would be more profitable to stop appealing to everyone and to only appeal to men. In hearing that today now, we have a knee-jerk reaction against it, though I would say that even having a magazine specifically for gay men that was about luxury and lifestyle and fashion was an interesting proposition at the time. The joke was, Details was in the closet and Out was out of the closet. Details would put a drenched guy in white t-shirt on their cover, and Out would be like, “Let’s just take his shirt off.”

There’s an honesty to that strategy, right? For one thing if you’re talking about men you’re talking about people with higher incomes in the US. And a household with two male incomes – that’s some spending potential.

PP: That was the logic at the time. What ended up happening was in the community, Out eventually became a bastion of white gay male privilege and this sense that even though we’re all in this struggle for equality together, the first people to benefit will be the gay white men.

Especially the married ones!

PP: Exactly. The more you assimilate….

Now you have Hari Nef on the February cover, who is a trans activist. Congratulations, by the way, on your first issue.

YS: Thank you!

PP: It feels wild. I was here in Paris when it dropped so it’s really strange.

YS: Tell the story of how we basically constructed the entire issue in two weeks.

PP: Normally when you start at a magazine, there are months of things planned. So I came in and I had three weeks until the drop, and I was like, “Oh, they must have planned most of it.” But nothing was planned, not a cover or a single page. So in one week, we had to create the lineup, and it was only me plus two people. And then everyone else started trickling in. My designer started first – our art director, Sean Santiago. Yashua started after Thanksgiving and called in all the fashion for 40 pages of editorial, and we shot the whole center of the book in one and a half weeks.

Presumably the ads were already sold.

PP: Ads were already sold.

Was there enough excitement around the transition that people were open to diving in and meet you on that schedule?

PP: I think overwhelmingly so.

YS: What sort of what happened with Phil getting Out, thank God, was – you know, he was this person who represented this young, generational voice that was really missing, and because he’s coming from Teen Vogue, he has a huge platform in terms of visibility about what he was doing. I think that gave us the ammunition from a fashion perspective to do exactly what we needed to do. There wasn’t much time, but we knew that with that we could at least get the content elevated. And that’s what we did. Now this is my first time traveling for men’s shows and doing Milan and Paris, and everyone reached out to greet us. The fashion community can be very fickle, so that was really reassuring and refreshing for this community. I also think that right now is a particularly interesting time to be taking on the brand, because people are actually really ready for Out to be something, after a history that’s been hit-or-miss. Now people want to be aligned with supporting a community and they can do that in ways that are as simple as buying a page of advertising or banner ad, or sending samples for a shoot. I think people want to be send a message that they are supportive.

Do you feel like it’s sustainable? This momentum?

PP: Momentum is never really sustainable. You kind of get used to that as a concept. I’m used to working on a digital platform, and it’s really hard to maintain digital momentum regularly. And what happens when you create momentum that’s designed for the internet is you start to look like a stunt queen, you start to look like you’re trying to get clicks or trying to go viral. And there are certainly titles out there who we all know design their brands around “breaking the internet,” so to speak. That makes it interesting to work in print, where we’re able to hopefully make a statement month after month that varies in its tonality, that varies in its style, that may vary in its impact, but that we’re not trying to impress the whole internet with. We’re not trying to go viral. We’re actually just trying to impact different sectors of our community and surprise the people who have never looked at us before.

There is a sustainability measure in that, really – sustainability is doing the ground work.

PP: We’ve been intentional about building an editorial calendar that focuses on themes, and so we think really critically every time about the themes. We’re working on the beauty issue. We’re shipping our women and non-binary femmes issue. Each time, we’re always thinking like, “Who have we missed? Who’s left out?” How do we make up for, how do we redress some of the wrongs that we’ve created as a publication? And also, how do we do something that is going to make people really excited? It’s not so much about people talking. It’s not so much about people being shocked. It’s about what’s going to make it feel good and representational.

You have to balance the breadth of interest of the audience with the depth the various readerships expect. But you also need numbers and retention because that’s income. You were involved with the transition from ten times a year to quarterly at Teen Vogue – what was the strategic thinking behind that?

PP: There was not a lot of strategic thinking. It’s very easy to say that the print edition’s shuttering reflects on the brand as a failure. But what I would say to the rest of the company is, it happened to us first, it’s happening to y’all next. We’ve already seen it happen.

Going quarterly’s no tragedy, obviously. But the messaging looked so wrong at the time because the brand was so strong, and if anyone was in a position to actually innovate the print model, it wasn’t going to be the Bon Appetit people or whatever.

YS: You mean the dinosaurs?

I mean, if anyone’s going to be responsive and evolve what you’re supposed to do in a print context, it’s going to be the people who are innovating online as well. And this kind of weird segregation between the digital and the print media is so boring, first of all. You know, saying print or whatever medium is “dead” has never been my thing. I find it so short sighted and alarmist.

PP: It is alarmist. I think especially to be in print as a queer title is so, so, so important because seeing us at newsstands may make a difference in someone’s life, even if they’re not able to pick up the magazine out of fear of being identified publicly. Seeing it at newsstands matters.

You can’t track clicks on a magazine and that shit’s going to be really real soon – people are already so burnt out. I think they are ready for the next incarnation of print, and I think that’s going to come from marginalized communities. Print will be used to crystallize and mobilize in ways that won’t be tracked or sold or subject to suggested commercial content. Now let’s all try to sell that advantage to an advertiser in your print publication!

PP: Well we all know the advertising market is drying up for media, and we all have to figure out what our business models are and how we’re going to be sustainable. You guys have a good model.

I mean, it’s dynamic. We’ve hung on to our DIY sensibility and agility from the early years – you need that to be able to shift gears. We’ve worked out a symbiotic relationship between the concepts and the products. Intellectually, I know a good magazine means having a sense for the Zeitgeist, having foresight, and we really do. Emotionally though, I do fear people will stop caring about ideas that aren’t printed on a t-shirt. What are you guys afraid of?

PP: There’s something that’s been with me like a specter since we changed the mission statement in Teen Vogue and realized how high people’s expectations would be. We were always held accountable where other magazines, even Vogue, were not held to that standard. Because it’s one thing to always have to be chic or tasteful – all of that is like, some subjective vision of taste – but Teen Vogue was deemed an ally to young women. To live up to that standard as a fashion magazine is really hard. When we launched them, what I realized even more was that the whole community was now going to hold us accountable. Someone who read the site from the community could say, “This is not how I choose to be represented,” “I don’t think this is my experience,” or “I don’t think you’re doing enough, I don’t think you’re doing the good work.” And that gives me a lot of anxiety because there’s a part of you that wants to get it right every single day, every single time. When you publish 20 stories a day and 10 issues of the magazine a year with a 12-person team, that can be hard. We do our best, but it’s different to be held accountable by your own community, and it’s also different to feel like you’re letting your own community down.

It’s like the syntax has changed – magazines used to tell you what was good, and you were expected to simply aspire to that. Now a magazine has to listen, to represent and even catalyze a community. The aspirational model has flipped, or at least it’s more permeable. There’s back and forth, and you have to speak to a bunch of different types of people without half-assing what you say to any of them.

PP: It’s totally true. That was the big thing for people to get, and the vision for Out is similar: we have to listen to our audience and we have to create content that’s more representative, more diverse in terms of what or whom we cover. A lot of people thought that because I came to Out, that it was only going to be for young people now. For the whole year every issue has to have a multi-generational or inter-generational moment. Those kinds of moments feel really important – we have to make sure that we’re honoring the people who made it possible for us to all have these jobs and to be at this publication at this moment in time.

Credits

- Interview: Victoria Camblin