The Billion-Dollar Underdog: A24 and the Business of Cultural Capital

|Harriet Shepherd

Ray Mendoza and Alex Garland, Warfare, 2025

All images courtesy of A24 unless stated otherwise

A24 is the biggest breakout in US film since Miramax. Since 2012, the New York studio has redefined indie cinema, built a cult following, and followed a business model comparable to LVMH.

But what makes A24 resonate so far beyond the box office? Is it auteur-driven storytelling – or the world to which it affords access?

(left to right): Ray Mendoza and Alex Garland, Warfare, 2025, Bratton, The Inspection theatrical release poster, 2022, Talking Heads, 1984. Courtesy of Michael Ochs Archives

To become a member of the A24 Film Group on Facebook, you must answer two questions: “What’s your favorite A24 film?” and “Are ye fond of me lobster?”

To the uninitiated, the second question might sound like cryptic nonsense. To fans of The Lighthouse (2019), it’s a rite of passage. In Robert Eggers’ briny black comedy starring Willem Dafoe as a deranged sea god in human form, this question precedes a soliloquy of doom: a cataclysmic curse that damns a man’s soul to the depths for insulting his seafood. It’s a monologue turned meme. The group’s 167,000 members, who congregate to unpack the intricacies of their favorite films across hundreds of posts each month, are united not just by their taste in cinema but also by their fluency in its niche codes. To enjoy Hereditary (2018) or Uncut Gems (2019) is not enough. You must be tapped in.

A24’s reputation precedes it, and that’s no accident. Leaning into its own mystique, the studio rarely gives interviews. In the 13 years since its founding, it has evolved from indie New York distributor to cultural shorthand – building a 3.5-billion-dollar brand, with Academy approval in the process. Its ambitions are increasingly expansive: 2025 promises appearances from Charli XCX, A$AP Rocky, and FKA Twigs; major international expansion through an exclusive Japanese output deal; a partnership with Nordisk Film; and a growing UK office now leading coproductions with the BBC and Film4. It’s also going bigger than ever on budget – with 70 million dollars backing each of the now-solo Safdie brothers’ next features: Marty Supreme, Josh’s surreal ping-pong odyssey starring Timothée Chalamet; and The Smashing Machine, Benny’s brutal biopic led by Dwayne Johnson.

But how did a studio once known for moody loners, cursed families, and occult farm animals come to define a cultural era – wherein horror could be highbrow, grief could be aestheticized, and obscure indie films could spark not only Oscar buzz but also eBay bidding wars? And what does it mean when a film studio becomes a personality trait?

“We broke records with how bad it tested.” – David Fenkel, A24 cofounder

Harmony Korine, Spring Breakers, 2012

AUTOSTRADA 24

The story goes like this: A24 was born on an Italian motorway in 2012. Or rather, New Yorker Daniel Katz was driving along the Autostrada 24, which connects Rome to Teramo, when the idea for a distribution company struck. The tale has the off hand poetry of a Tumblrera aphorism, like naming your band after a Jack Kerouac reference. It doesn’t really mean anything, and yet it does – it suggests spontaneity, romanticism, a sense of the cinematic in everyday life. It fits the myth that A24 would later build around itself: that of an instinct-driven, taste-forward company born out of a feeling rather than a formula. A name with no obvious meaning, just the right vibe.

Before A24, its three founders – Daniel Katz, David Fenkel, and John Hodges – had navigated different corners of the film industry. Katz had spent years in investment banking before moving into film distribution at Guggenheim Partners, where he learned the financial architectures of modern moviemaking. Fenkel had helmed Oscilloscope Laboratories, the indie outfit he cofounded with Adam Yauch of the Beastie Boys, specializing in the kind of boundary-pushing documentaries and off-kilter narrative films that major studios wouldn’t touch. Hodges came from Big Beach, the production company behind Little Miss Sunshine (2006). COO Matthew Bires would join A24 later, though he’s sometimes miscredited as a cofounder.

By 2012, the American independent film scene that had been so formative for A24’s founders had calcified into something almost unrecognizable. The rebellious energy that had animated 90s cinema – when Miramax was minting money with Pulp Fiction (1994) and early Focus Features established Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation (2003) as an instant classic – had given way to major studios doubling down on data-driven franchise tentpoles. The cinematic climate of that year was dominated by superhero sequels (The Avengers, The Dark Knight Rises), reliable reboots (The Amazing Spider-Man, Skyfall), and safe prestige fare such as Argo and Life of Pi.

While such acclaimed international auteurs as Thailand’s Apichatpong Weerasethakul and France’s Claire Denis created boundary-pushing work with support from national film institutions in other countries, distinctive US voices such as Jordan Peele and the yet-to-emerge Ari Aster were operating at the periphery of an industry that had forgotten how to take meaningful creative risks. The gulf between international art cinema and American theatrical distribution had never felt wider.

A24 launched into this void, not from Hollywood, but from a small office in New York. It didn’t come out swinging with a manifesto, and gaining trust wasn’t easy. The first film it acquired, A Glimpse Inside the Mind of Charles Swan III (2012), was a clunky, “self-indulgent” misfire from Roman Coppola that has a 16 percent critic score on Rotten Tomatoes. The film starred Charlie Sheen, who didn’t bother showing up for the premiere. That same year, A24 shot for the stars with Frances Ha and The Place Beyond the Pines (both 2012), but attempts to secure distribution rights were ghosted, as these films were out of their league at the time. It did, however, manage to win over the team behind Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers (2012) the only way it knew how: getting interns to source hand-blown glass bongs in the shape of guns to give to the producers in Pittsburgh.

Personally, I enjoyed the movie. Others definitely did not. Multiple walk-outs occurred at the film’s test screening in Manhattan. “We broke records with how bad it tested,” A24 cofounder David Fenkel told GQ in a rare 2017 interview. “Every time another person walked out, I was, like, ‘Oh, there goes another one!’” added former A24 exec Nicolette Aizenberg. It didn’t faze them. It made Harmony Korine laugh. It was a perfect disaster, underpinning the reasons for the studio’s founding: there was power in provocation. Spring Breakers was weird and sticky and unashamed. It was the kind of film you had an opinion about. The kind of film that got you talking.

(left to right): Alex Garland, Civil War, 2024, Barry Jenkins, Moonlight, 2016

A24 WITH A CAPITAL A

Over the next few years, A24 built its alternative signature. It acquired buzzy festival hits and began forging a reputation not just for taste but also for vibe. It showcased artistic and unconventional stories that felt timely, astute, even eerily prescient. Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin (2013) had its alien predator (Scarlett Johansson) scouring Scotland for intimacy-starved men to engulf – set to Mica Levi’s skittering score of scratching strings and disembodied percussion. A haunting meditation on loneliness and desire, it captured male alienation in the digital age before “incel” had entered the mainstream lexicon.

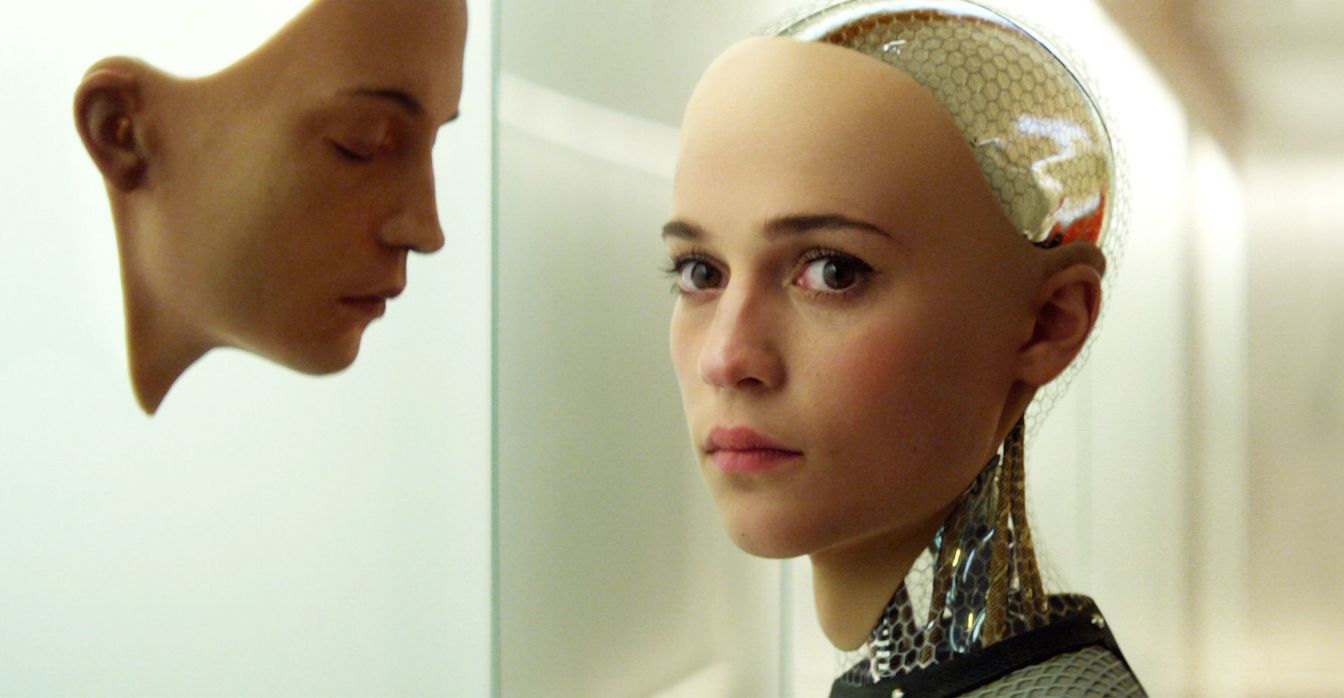

Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring (2013) channeled the ambient nihilism of early, celeb-obsessed influencer culture. Alex Garland’s Ex Machina (2014) landed just as Silicon Valley’s techno-optimism was beginning to give way to unease, and Alicia Vikander’s uncanny android prefigured the AI anxiety that continues to plague us a decade later.

A24 bet on uncompromising personal visions that often made its (niche) audiences feel unsettled. “They established themselves as synonymous with independent filmmakers, unconventional plots, and unconventional content,” says Ana Andjelic, brand analyst and author of Hitmakers: How Brands Influence Culture (2024). As visual culture was being radically reshaped by such platforms as Instagram and Tumblr, A24 seemed to intuitively grasp what traditional studios could not: that younger viewers were developing new perceptual frameworks that were nonlinear and associative. This new generation was one fluent in vibes and allergic to exposition, and more emotionally literate than its predecessors.

It distributed director-driven films that were polarizing, often emotionally charged, and that other studios would not dare risk. Whereas Hollywood sticks to safer, four-quadrant crowd pleasers, 92 percent of A24’s 25 top-grossing films are R-rated. “I can’t believe I made The Witch,” Robert Eggers admitted of his 2015 debut on an episode of The A24 Podcast. “It’s nuts.” Slow-burn horror about a Puritan family unraveling in the New England woods, The Witch features no jump scares and no stars. Shot in candlelight and written/performed in 17th-century English, it should have been a hard sell. Yet A24 backed it, branded it, and sold it as a must-have object of taste. It gave the first-time filmmaker creative freedom to make an eerie, theologically dense period piece – and turned it into a commercial and critical hit that launched a theretofore unknown Anya Taylor Joy’s career. A24 followed that film with Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017) and Ari Aster’s Hereditary (2018) – featuring Toni Collette’s shattering portrait of maternal grief – and further codified a brand of what critics dubbed “elevated horror”: one concerned less with monsters than with psychological disintegration.

(left to right): Peter Strickland, In Fabric, 2018, Luca Guadagnino, Queer theatrical release poster, 2024

But its output wasn’t limited to any single genre. There was Asif Kapadia’s Amy (2015), which delivered an intimate portrait of Amy Winehouse’s spectacular rise and tragic fall and earned an Oscar for Best Documentary. Noah Baumbach’s “laugh-out-loud” comedy While We’re Young (2014), which starred Ben Stiller as an uptight middle-aged filmmaker who is pulled out of a rut when he and his wife encounter a young free-spirited couple. And then came Laggies (2014), a peppy rom-com starring Keira Knightley, and the coming-of-age drama American Honey (2016).

By 2016, A24 made its crucial transition from distributor to producer with Moonlight, Barry Jenkins’ poetic coming-of-age triptych set in Miami. The film depicted Black, queer masculinity with a tenderness and vulnerability that American cinema had systematically erased. At an Oscar ceremony immortalized when La La Land was misannounced due to an envelope mix-up, Moonlight won Best Picture. A24 became synonymous with authentic representation that the industry was still learning to recognize. It more than doubled its line credit, and it secured a multiyear partnership with Apple and a broadcast deal with Showtime. By 2017, Vanity Fair was asking whether A24 could be the next Miramax. Vulture gushed over its “auteur-driven” and “visually stunning” output and praised its “offbeat sense of humor.” The Guardian later described it as a studio that “finds the zeitgeist and sets the trend.” By 2018, The New York Times acknowledged that “plenty” in Hollywood “believe A24 is overhyped ... perhaps nudged along by envy,” but that even those people had to concede “that the studio has done an astounding job at building a brand.”

The subsequent years were marked by a string of standouts that further solidified the “house style” that wasn’t. The Florida Project (2017) explored the poverty on Disney World’s doorstep through a child’s Technicolor gaze; Lady Bird (2017) filtered millennial coming-of-age through a soft, sun-faded Sacramento palette. In Eighth Grade (2018), Bo Burnham captured the social anxiety and digital hyperawareness of Gen Z with raw, near-documentary intimacy, whereas Jonah Hill’s Mid90s (2018) mined skate culture and boyhood in grainy 16mm. Frenetic and fluorescent, Uncut Gems (2019) channeled the coked-up velocity of a capitalist system designed never to let you win. Minari (2020), grounded in golden-hour naturalism, reimagined a rural Korean American dream. Medieval, fog-cloaked masculinity was reconfigured post #MeToo in The Green Knight (2021).

Fans connected with the emotional realism of these stories – subtle, lived-in portrayals rarely found in mainstream film or TV. When Sam Levinson’s Euphoria hit HBO in 2019, it resonated with a generation craving unvarnished depictions of youth. It traded moralizing for messy truth – far removed from the after-school-special tone that defined millennial adolescence. Quiet, dialogue-driven, and emotionally raw, Hunter Schafer’s cowritten episode marked a watershed moment, not only for representation, but for trans authorship in mainstream television.

“There was a sense that these stories couldn’t have existed elsewhere,” explains fashion writer and cultural critic Biz Sherbert, who praises A24’s attention to small details. “It feels very nuanced to me. Midsommar (2019) was one of the first movies I watched where it felt like an A24 movie with a capital A. I remember Dani – Florence Pugh’s character – is ... wearing these kind of saggy sweatpant shorts, and it’s supposed to reflect her depression after her family dies. I felt like that was an element of realism that I ... hadn’t seen in styling – at least, [not before] that point in my life.”

“Everything is merchandisable, especially cultural capital.”

Traditional studios are notorious for creative interference – test screenings that lead to rewrites, notes from executives trying to maximize box-office appeal, decisions made by marketing departments rather than by artists. “It just feels like films have become directed by committees from nameless, faceless places far away,” says Brendan Fraser – star of The Mummy franchise and of A24 Oscar-winner The Whale (2022) – in an episode of the studio’s podcast. “A24 doesn’t get in [the director’s] way. I love that about them.”

A24 didn’t invent the idea of filmmaker-driven storytelling, but it offered a version of it that actually worked in the US – adding value through absence rather than presence. “You might think established filmmakers have an easy time making and funding their films,” says Mads K. Mikkelsen, film lecturer and head programmer at CPH:DOX film festival. “But that’s not the case.”

Instead of imposing its own rules, A24 refuses to sand down a film’s essential strangeness, and that stance quickly became its hallmark – establishing its own identity by believing in the ideas of others. It gave filmmakers not only financing and distribution but also breathing room, allowing rare creative control that often included the final cut – a privilege typically reserved for such established auteurs as Christopher Nolan or Quentin Tarantino. If the story was strange, ambitious, and personal, that wasn’t a liability – it was the point.

Harmony Korine, Spring Breakers, 2012

THE DISCOURSE

When Zoe Beyer joined A24 in 2012 as an intern, social media remained untamed territory. Instagram had just been bought by Facebook. Tumblr was nearing its peak. Twitter users had all but doubled in the span of a year. Reddit’s monthly page views accelerated to 37 billion. As a start-up studio with no antiquated playbook to unlearn, A24 seized the opportunity to inject itself into the cultural blood-stream through the internet’s open veins. Beyer architected the studio’s distinctive online voice – irreverent, ironic, and often entirely unrelated to A24 – and its devil-may-care marketing strategy with such precision that she ascended from intern to A24’s creative director, a trajectory almost as remarkable as the studio’s own rapid rise.

Under Beyer’s direction, the studio crafted digital performance art instead of advertisements. It catfished Tinder users with AI seductress Ava (Alicia Vikander) to promote Ex Machina. It tweeted demonic prophecies as the satanic goat from The Witch. In 2018, it mailed out nightmare-inducing dolls “handcrafted” by Hereditary’s possessed child. It printed Robert Pattinson’s face onto actual pizza boxes circulating through New York City’s grease-stained economy and faked texts from Daniel Radcliffe’s farting corpse to advertise Swiss Army Man (2016).

A24’s strategy relied less on spending and more on specificity. Its films weren’t mass-market by design, so the marketing didn’t need to be, either. Instead, its guerrilla theater spoke directly to an audience starved for authenticity in an increasingly corporate landscape – an anti-brand brand that, paradoxically, became one of the most recognizable signatures in contemporary American cinema.

But A24’s most savvy business move wasn’t its digital hijinks. That move was recognizing and nurturing a fan base unlike any other in independent film. By the mid-2010s, A24 had cultivated a new kind of viewer: terminally online, fluent in memes, and deeply invested in the studio’s output. A24 didn’t sell films so much as embed them into the discourse – capitalizing on the “WTF did I just watch?” feeling many of its films evoked.

(left to right): Ti West, X, 2022, Alex Garland, Ex Machina, 2014

These fans made Letterboxd their diary, made memes of an “A24 film fan meetup” that took place outside a building clearly labeled MENTAL HEALTH CENTRE. A24’s subreddit ranks in the top 1 percent of all Reddit communities. Its 3 million–strong Instagram following exceeds the following of Rick Owens and is more than twenty times that of Magnolia Pictures. In the past year alone, dating app Feeld has noted a 65 percent increase in people listing A24 as an interest on profiles – one that overindexes for women, nonbinary people, and bi/pan users, demographics that mainstream film culture often sidelines. The archetypal A24 fan became an internet micro-archetype in itself: the girlie fluent in both Jungian trauma theory and The Witch (2015) or the Criterion-shelf film bro with an attachment disorder. What Biz Sherbert sees as a reductive “evolved hipster” stereotype – “people who identify with A24 and wear it as a personality trait.”

A24 super-fandom is, of course, more chaotic and contradictory than any memeable Venn diagram could suggest. The gatekeepers of its subreddit alone have varied interests: one mod is also responsible for the Death Grips forum; another moderates Sims 5; another helms a page to snark on “momfluencer” Acacia Kersey. Rather than distance itself from this image, however, A24 leaned into it, recognizing that, in late capitalism, everything is merchandisable, especially cultural capital. It scaled horizontally, aligning itself not just with taste but also with taste-making through collaborations involving clout-swollen streetwear brands – Online Ceramics, Boot Boyz Biz, and Brain Dead – to produce sell-out drops that would end up on Grailed. It released high-concept and artful merch: a Hereditary gingerbread-house kit (65 dollars), a Lighthouse-themed beard oil set, genre-scented candles – offkilter collectibles that functioned as a kind of inside joke for those who had seen its films. A24 understood that fans didn’t just want to watch movies, they wanted to own and inhabit them – and that doing so built both currency and community.

“When Euphoria first came out, people were just wanting to copy the looks that they saw on the show one-for-one,” says Sherbert. A24 leaned into the momentum – not just by reposting memes but also by launching an entire beauty brand, Half Magic, run by the show’s makeup artist Donni Davy. It invited Alexa Demie and Nathan Fielder onto its podcast in what remains the most popular episode to date. It commissioned Sherbert to write for Euphoria Fashion (2022), a book dissecting the style from the season, which joined its growing library of experimental and often form-forward publications: Minari Song Reader (2022), 16 sewn booklets of sheet music and lyrics from its score; a cookbook of recipes inspired by horror films; and even titles not directly related to the studio’s output, such as Charlie Porter’s How Directors Dress (2024).

In 2022, it launched AAA24, a $9.99-per-month fan club offering exclusive zines, store credit, and free opening-weekend tickets. Members gained access to the studio’s Close Friends Instagram stories for behind-the-scenes content and monthly “Closet Cleanout” giveaways of rare archive merch. Notably, the subscription doesn’t include streaming access to films – what’s being sold isn’t movies but instead proximity to them: identity, community, clout.

A24’s brand model has been compared to LVMH – a useful parallel when understanding A24’s multi-pronged identity. As Andjelic explains, A24 has evolved from a “House of Brands” – where “the movies are treated as separate brands,” each with its own activations and marketing – toward a more synchronized model. “They have one A24 umbrella name, and they have separate, independent brands [beneath] it, which have sort of similar DNA to the core idea of A24: supporting independent filmmakers and filmmaking and providing an alternative to the mainstream.”

Shifting into source brand architecture, A24 reinforces a sense of brand identity by synchronizing distribution and marketing. “That can help them tighten up their studio brand,” Andjelic says. Like LVMH, which spans from Louis Vuitton to Celine and Fendi to Rimowa, A24’s brand now stretches across content verticals that reflect, but also reinforce, its core aesthetic. The difference is that A24 is not exporting luxury but instead curated weirdness, intimacy, and indie legitimacy.

(left to right): Danny Philippou and Michael Philippou, Bring Her Back, 2025, Jane Schoenbrun, I Saw the TV Glow, 2024

EVERYTHING, EVERYWHERE

As A24 flourished, its industry profile soared. Employees were confronted with a Devil Wears Prada (2006) moment: a million aspiring creatives would kill for their jobs. One producer told me that A24’s status was affecting their romantic life. They would get to the third date, then be handed a screenplay.

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022) marked the tipping point in A24’s evolution from cult favorite to cultural institution. The Daniels’ riotous, maximalist explosion of immigrant trauma, generational guilt, kung fu, and googly eyes embodied everything that traditional studios might have filtered out – and everything A24 strove to protect. “Actually fighting to be original and keeping that originality is one of the biggest tasks,” Michelle Yeoh said in retrospect. “That’s where A24 really helped us. They didn’t give [the Daniels] notes to say, ‘What? What’s with the hot-dog fingers?’”

It paid off. The movie was also A24’s biggest commercial and critical success to date, grossing more than 140 million US dollars worldwide on a 14-million-dollar budget and winning seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, and historic acting wins for Yeoh and Ke Huy Quan. With Brendan Fraser winning Best Actor for A24’s The Whale (2022), that was the first time in the 95-year history of the Oscars that a single studio swept all major categories.

“A24 is not exporting luxury but instead curated weirdness, intimacy, and

indie legitimacy.”

Those wins constituted the crowning achievement of A24’s first decade – and the numbers speak for themselves. That same year, growth equity firm Stripes (which also invested in Erewhon and Reformation) acquired a 10-percent stake in the company at a valuation of 2.5 billion dollars – a once inconceivable figure for an independent studio.

Two years later, A24 secured a new round of funding led by Thrive Capital, upping the studio’s value to 3.5 billion dollars. Such capital infusion has enabled it to expand its production slate; acquire the historic off-Broadway theater Cherry Lane; and support its offshoot production company 2AM (responsible for Bodies Bodies Bodies [2022], Babygirl [2024], and Past Lives [2023]) – all while continuing to back filmmakers who, otherwise, struggle to secure financing.

But as A24’s cultural footprint expanded, so did the skepticism from critics, fans, and purists concerned that the company was diluting what mattered most. In 2022, Vulture’s Nate Jones suggested that A24 was “teetering on the verge of self-parody,” while competing distributors positioned themselves in opposition to A24’s lifestyle approach. In 2017, Tom Quinn, founder of independent studio Neon, told Deadline, “I can assure you that what we will not be doing is selling $50 candles .... It feels inauthentic. We’ll continue to focus on the things that are really meaningful – our filmmakers and our audience.” Fast forward four years, and Neon is selling Anora (2024)–inspired “Little Wifey” thongs for 15 dollars and decorative monkey figurines for 125 dollars.

This tension between artistic integrity and commercial reality emerges playfully in an episode of The A24 Podcast, where acclaimed authors Ocean Vuong (On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, 2019) and Bryan Washington (Memorial, 2020) discuss adapting their works for the studio.

Bryan Washington: I feel so fortunate to get to work with [A24] and to see the project through. And that’s not solely because we’re on their podcast. It’s not bullshit.

Ocean Vuong: No.

BW: They do such great work. OV: And it’s going to be good merch. [laughs]

BW: Yeah, yeah, the sweaters, the hats. Honestly, like, that’s the reason.

OV: You know the merch’s going to be fire.

BW: It’s going to be fucking crazy.

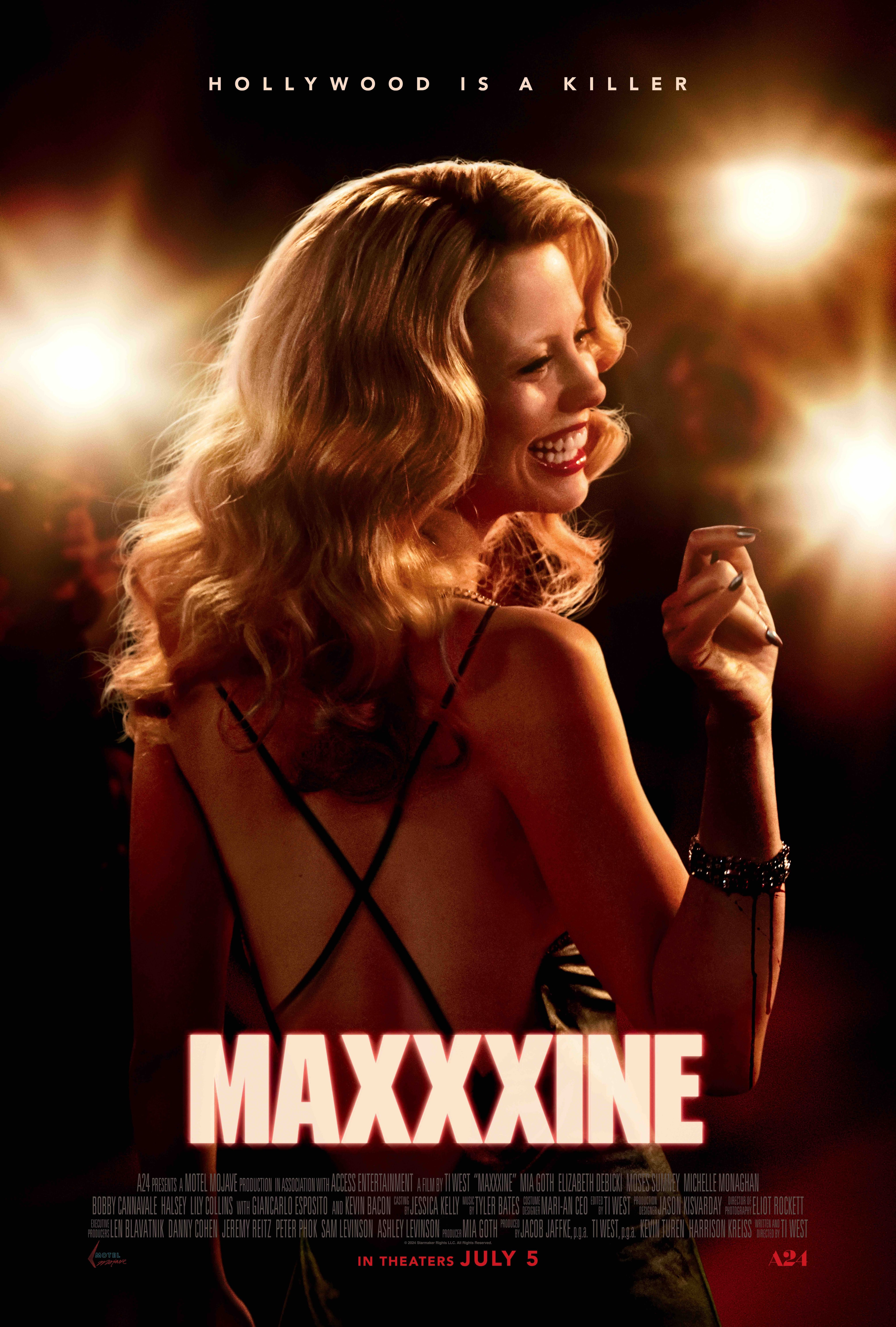

(left to right): Greg Kwedar, Sing Sing, 2023, Ti West, MaXXXine, 2024

“A24 is not exporting luxury but instead curated weirdness, intimacy, and indie legitimacy.”

Their gentle mocking belies a truth that cinephile purists often neglect: the brutal economics of independent filmmaking in the US. A24’s horizontal expansion isn’t just cultural positioning but also financial survival in an industry where theatrical windows have shortened and streaming giants increasingly dominate distribution. A minuscule 3.4 percent of all independent films made in the US over the past two decades were profitable. Almost 60 percent of the independent films that made it to cinematic release did not recoup their production costs. The lifestyle brand strategy that purists decry has, paradoxically, created the economic conditions necessary for artistic risk-taking.

DEATH OF A UNICORN

This business success has only intensified the mythology surrounding the company. I asked an anonymous source close to A24 what misperceptions exist about the company’s internal culture. “That we’re trying to be ‘cool’ and perhaps full of ‘mystique,’” the source replied. They contend that the company’s actual focus is much simpler: spotlighting creators and their stories, which A24 considers far more compelling than its corporate identity.

This response itself might seem paradoxical – reinforcing such mystique by requesting anonymity – yet much of A24’s enigmatic aura does appear externally imposed rather than deliberately cultivated. Baseless rumors run rampant (Is Willem Dafoe starring as Aphex Twin in an A24 biopic?). When it launched an Instagram account for A24 Music in April, media outlets leapt to analyze the cryptic soft launch of a supposedly new venture – overlooking the fact that the music division had actually been operating for three years and has already released numerous projects, including the Love Lies Bleeding (2024) vinyl featuring Chinese American painter Amanda Ba’s artwork.

The inevitable conclusion of the hype cycle is fatigue. “All hype comes with a vengeance, and A24, for sure, has been hyped up,” says Mikkelsen. “Most of the films can sustain the hype, I would say, but they’ve also been very targeted to specific groups of people – this modern version of fan culture.”

At its most extreme, A24 appreciation can verge on cultishness – a symptom of what Quentin Tarantino diagnosed, in 1994, as Hollywood’s desperate outsourcing of judgment. “This is a community where hardly anybody trusts their own opinion,” he told the BBC. “People want people to tell them what is good.” The A24 logo has become a shortcut to discernment, a merchandised moodboard of good taste. “They’ve become a shortcut to a subculture,” says Andjelic. “You just see one movie, buy some merch, and you’re good. You signal something very quickly.”

(left to right): Isaiah Saxon, The Legend of Ochi, 2025, Ti West, MaXXXine theatrical release poster, 2024

In that sense, some of the fatigue stems not just from overexposure but also from what A24 has come to represent: a kind of off-the-rack identity. The studio offers cultural capital with minimal investment – the illusion of individuality without the effort of developing it. Vulture’s Sam Sanders characterized it succinctly: “When moviegoers gush over an ‘A24 film,’ it can be hard to tell whether they’re more excited about the ‘A24’ part or the ‘film’ part.”

The breathless celebration of A24 as cinema’s saving grace reflects a distinctly American myopia. Although the studio has undeniably created space for certain kinds of challenging films within the Hollywood ecosystem, to focus exclusively on A24 risks obscuring the vibrant cinema emerging globally. Whether the social critiques of South Korea’s Bong Joon Ho (whose Parasite from 2019 was distributed by Neon, not A24), the formally daring films of Senegalese French director and actress Mati Diop, or the haunting narratives of Iran’s Asghar Farhadi, the most innovative filmmaking often happens far from American shores, with far less branding fanfare. This US-centric perspective becomes particularly apparent when examining A24’s actual output against the broader backdrop of global cinema.

Recent stumbles have only sharpened the backlash. The Idol (2023) was savaged by critics as one of the worst shows ever made. Critical flops have coincided with audience disappointments. Ari Aster’s Beau Is Afraid (2023) was dubbed “ box office poison.” It made back only a third of its 35-million-dollar production budget, with critic Erick Weber calling it, via Twitter, a “0/10 ... career-killing ... dumpster fire that #A24 needs to answer for” and “what happens when studios cede full creative freedom to directors with reckless disregard for audiences outside themselves.”

Even the studio’s commercial ambitions have raised eyebrows. Last year, A24 lost out on a deal to make league-sanctioned films for the NFL, suggesting a pivot toward more middlebrow mass appeal. Bloomberg asked whether “the masters of hipster cringe” could finally go mainstream.

There is authenticity in restraint. As a brand strategist, Andjelic affirms the need for clear boundaries: “You say, for example, ‘We’re never going to do a Hollywood movie. Never something bigger than XYZ in terms of budget.’” I ask a close source what A24’s non-negotiables are as the company scales – what lines it won’t cross to avoid diluting its essence. The source responds with striking simplicity: “None.”

“A24’s horizontal expansion isn’t just cultural positioning but also financial survival.”

Brady Corbet, The Brutalist, 2024

With its newest valuation, the pressure to expand is undeniable. Beyond scaling operations, A24 faces the challenge of maintaining relationships with the very directors who helped build its brand. The mixed critical reception to Aster’s sprawling, ambitious Beau Is Afraid reveals this delicate balance – supporting an auteur’s vision while managing both artistic and commercial expectations. As directors such as Greta Gerwig (who moved from Lady Bird to Warner Bros.’ billion-dollar Barbie [2023]) and Robert Eggers (whose Nosferatu [2024] landed at Focus Features) demonstrate, early success at A24 often leads to bigger opportunities elsewhere. Each departure potentially undermines the studio’s carefully constructed identity and makes talent retention not just a personnel issue but also an existential one for a brand built on distinctive voices.

And perhaps those who cling to the fantasy of A24 as a scrappy independent studio are preserving a mythology that never fully existed. It produces arthouse films and also Amazon Prime’s most-streamed animated series, Hazbin Hotel (2019 –). It is helmed by execs with Wall Street experience. It buys downtown theaters and courts billion-dollar valuations.

People also often pit indie studios against one another – A24 versus Mubi versus Neon – but, in reality, these companies operate within an interconnected and often collaborative ecosystem. A24 distributed After-sun (2022), a Mubi production directed by Charlotte Wells and backed by BBC Film and the BFI. It has partnered with Film4 on multiple titles, including The Zone of Interest (2023), which it codistributed with Sideshow and Janus Films. It has ongoing relationships with Brad Pitt’s Plan B (Moonlight, Minari, Women Talking), Square Peg (Beau Is Afraid), and IAC Films (Uncut Gems, Hereditary).

These collaborations suggest less a siloed auteur factory and more a broader web of shared financing, creative labor, and infrastructure. Rather than being a singular force of innovation, A24 functions more like a conductor in a creative orchestra – amplifying what already exists and lending it a particular sheen. For all the mythology of A24 as a self-contained phenomenon, the reality is more interdependent. Its success is contingent upon the support, risk, and talent of the entire indie film ecosystem.

A close source insists that A24 has no interest in perpetuating an underdog narrative. Albeit proud of the studio’s origin story, the studio’s team constantly looks forward and outside the box: What’s the 2026 vision of A24?

(left to right): Daniel Scheinert, The Death of Dick Long, 2019, Valdimar Jóhannsson, Lamb, 2021

A2026

What A24 has accomplished once seemed unthinkable: transforming a production company into a pop cultural code. In an era when only 10 percent of Gen Z prioritizes film and television as entertainment, A24 has become a bridge between traditional cinematic experience and digital-native sensibilities. “I don’t think there’s anywhere that this generational shift is more visible than with A24,” notes Mikkelsen, highlighting cinema’s increasingly rare capacity for sustained attention. “It’s the last place where you can really go beyond yourself .... You go to this weird house, you sit in the dark, you don’t talk to anyone .... You’re inside the mind of somebody else for two hours, and that’s healthy.”

A24 now stands at what Andjelic sees as a “critical crux” in its trajectory. “I do think that A24 is moving in that ambient phase of their lives if they don’t change,” she says. The precedents aren’t encouraging: “There will be these fluctuations where somebody like Wes Anderson all of a sudden became more like a coffee table object than a filmmaker,” Mikkelsen says, “and where certain aesthetics that, for a while, were fresh and fun turned out to not really have a forward movement.”

“There will be these fluctuations where somebody like Wes Anderson all of a sudden became more like a coffee table object than a filmmaker.”

– Mads K. Mikkelsen

(left to right): Alex Garland, Civil War, 2024, Halina Reijn, Babygirl theatrical release poster, 2024

But A24’s most valuable contribution is, perhaps, precisely what its detractors mock: creating a cultural output that provokes genuine bewilderment. Many of its best films are esoteric, obscure, and open-ended. Its business moves have a tendency to confound industry expectations. This perpetual state of unpredictability – on screen and in corporate strategy – demands constant reassessment, and it propels viewers and industry observers alike toward deeper engagement rather than toward passive consumption.

Andjelic proposes that A24’s forward movement could be to fully harness this potential and move into Endorsed Brand architecture. It endorses collaborators; curates other cultural products; and applies its distinctive filter beyond film to “books, cities, locations, people, art, design.” Despite Mikkelsen’s dismissal of taste as “corrupt” and “internalized censorship,” Andjelic recognizes its market reality: “They expand their reach ... they’re going to reignite that active creation of taste.”

Still, the most intellectually honest way to engage with A24 is neither to dismiss it, nor to uncritically idolize it, but to meet each film on its own terms – outside the glow of the brand. Cinema’s future depends not on any single studio’s catalog – American or otherwise – but instead on dismantling the geographic, economic, and institutional barriers that keep so many stories from reaching audiences. A studio, at its best, should be a portal, not a destination.

When the “post-A24” era inevitably arrives, its legacy won’t be memorialized in hoodies or tote bags but in having executed a cultural insurgency against the tyranny of algorithmic determinism. While streaming platforms dismantled traditional cinema’s business model, they simultaneously threatened its aesthetic soul – replacing the film as coherent artistic statement with content as personalized consumption unit. A24’s genius was not in rejecting commerce but in weaponizing it, in using the mechanisms of contemporary branding to create space for precisely the kinds of challenging, unresolved narratives that algorithmic curation systematically suppresses. By converting curiosity into cultural capital, the studio performed an aesthetic judo throw against platform capitalism’s core logic – thus proving that audiences could be trained to desire the discomfort of not knowing rather than the comfort of being known.

Credits

- Text: Harriet Shepherd