Dreamers: The Belgrade Biennale, and Its Afterlife

|Victoria Camblin

“A product of the wandering fancy that Gaston Bachelard called rêverie —the source of imaginative thinking, the dawning of consciousness, the primal dimension of the human being—The Dreamers literally embodies the presence of other worlds that proceed, as dreams do, by free association and in scraps, with images and allusions that ricochet between dreams, imaginings, oneiric projections, the virtual sphere, and the real world. The story is fragmented, tentative, stuttering, fretful, sullied by the world, by gaps in memory and glimmers of light. Yet a story does emerge, as the driving force of thought.” Excerpt from “The Dreamers” exhibition catalogue

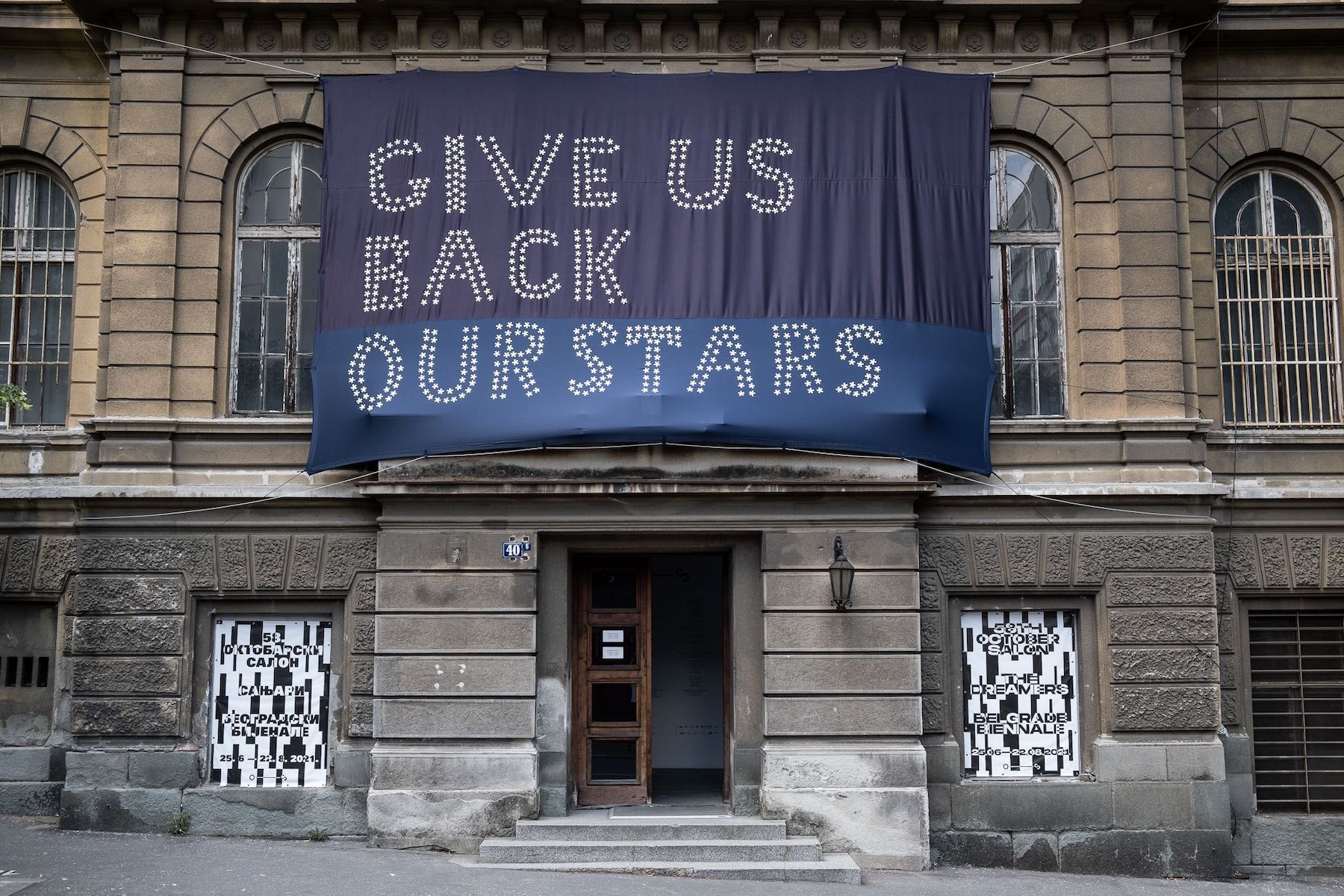

The 58th October Salon/Belgrade Biennale opened in late June 2021 following a year of pandemic-related postponements and various collateral upheavals – including a venue change only weeks before its public debut. The exhibition, titled “The Dreamers,” seemed enhanced, not compromised, by its non-linear genesis: in dreams, as in life, contexts morph without notice, and as the rules of the game change, our psyches somehow adapt. So did curators Ilaria Marotta and Andrea Baccin, co-founders and editors-in-chief of CURA. magazine, and founder-directors of BASEMENT ROMA – a non-profit in Rome – and the Milan-based exhibition platform KURA. “CURA.’s activities are all related,” they say, and artists published in the magazine are often also involved in the exhibition activity, be that in Italy or in Belgrade.

Exhibition- and magazine-making are both practices of making public. Both daylight, decode, and redistribute the reciprocities and recurrences in our experience, making sense – or simply making something – of fragments that come to us intuitively. If dreams appear “senseless,” as Carl Jung wrote in “The Practical Use of Dream Analysis” (1934), it is because we “lack the sense and ingenuity” to read their enigmatic message. Psychoanalysis was a prevalent theme in the opening events, for which Max Hooper Schneider commissioned a Serbian band called Psychotherapy for a compelling activation of his site-specific installation outside the Museum of Yugoslavia, which contains the mausoleum of Josip Broz Tito. The performers – Psychotherapy’s Aleksandar Jestrović Jamesdin and Dejan Poljaković, plus Hooper Schneider’s intern on percussion – donned a combination of straight-jackets, “raccoon” facial prosthetics, and looks of despair to deliver songs about childhood memories and mother figures. Davide Balula’s performance cast glitter and spandex-glad participants to imitate bird songs and roam among visitors, like the proverbial “little birds” that tell us things we’re not supposed to know.

The dream, as what Jung called the “little hidden door” to the secrets of the subconscious, is a means of accessing not only our individual realities, but of dealing with collective experience, and with the past. In Belgrade, the vestiges of recent history remain in plain view. On the same block as the “The Dreamers’” primary venue, the Belgrade City Museum, is the carcass of the Yugoslav Ministry of Defense building: a masterpiece of post-war architecture bombed by NATO in 1999. Its ruins are now protected as a monument of culture, but a local taxi driver told me that “a developer will come turn it into a hotel soon.” Like most biennials, “The Dreamers” is implicated in the changing landscape of the city, not just through public commissions but in its absorption of the subliminal tensions and desires such transformations summon.

The biennale closed in Belgrade on August 22, but the program continues with “The Dreamers: An Echoing” – recurring, dream-like, as a roving series of video screenings, performances, and events presenting key works in Italy, online, and elsewhere, kicking off this week in Rome with a performance by Nora Turato called what is dead may never die. The Dreamers Library, originally installed at the Cultural Center of Belgrade, is now an ongoing project that will grow as an “itinerant archive of publications, including essays, novels, and philosophical and science fiction books suggested by participating artists,” concluding – at least for now – with a book launch in London this October. The biennial and its afterlife are in this sense also about what Cura. does – about a curatorial and publishing practice in which dreaming, it turns out, is a cornerstone. “We dreamed of ‘The Dreamers’ long before we could see it realized,” say Marotta and Baccin. “Dreams are the impulse that carries on the spirit of what we do – often, they’re where it all starts from.”

Victoria Camblin: How and when did you arrive at the chosen theme for this edition of the October Salon?

CURA.: The theme arrived suddenly, one day upon awakening, in that semi-unconscious state between sleep and wakefulness when ideas often surface. The name of the exhibition, “The Dreamers,” actually came before the theme. It crystallized around the group of artists we wanted to involve – something that was very clear in our minds even before we began discussing the exhibition together. We were thinking of artists we have often worked and exchanged ideas with – artists who we grew up with and who have always given a strong thrust to our work. We define these “dreamers” as visionaries capable of critically observing the world, and of creating new ones. Once we identified the artists we certainly wanted involved, we noted and began to explore the theme of dreams and of what it means to be a dreamer – in all its complexity, universality, and topicality.

The biennial was postponed due to Covid, as many shows were. The works did not respond directly to the crisis, but how do you see the exhibition, and its theme, in the picture of the events of the last 18 months? Does it relate to the “real” world as a dream does to waking life?

Covid has only confirmed how close and real the dystopian nightmare is. Our proximity to that radical change, which was already quite clear and obvious to many, has become something the whole of humanity has had to deal with. We’re referring to the disaster that we have brought upon our planet, the wicked choices we’ve made against the Earth, the lack of respect for our planet’s biodiversity, the exploitation of intensive farming, the neglect of climate issues central to our own survival. Global hierarchies, great inequalities, and the nihilism of the digital sphere are some other themes that have arrogantly surfaced during the pandemic period. Isolated in our homes, we have also been able to relate much more clearly to ourselves, to our dwellings, and to the limits of our world. When we restricted our range of action, the dream space and the space of the imagination recovered some of the ground that was lost in the frenzy of the world. As virtual space became the only place of expression, artists began to partially or completely rethink their practices to respond to new demands and urgencies. What we witnessed was a general inclination toward a dematerialization of the artistic object in favor of ephemeral interventions, actions, and sounds; experiences centered on the here and now; and a recovery of history and one’s roots.

“In a computational world experienced through machines, technology, algorithms, augmented reality, facial recognition, surveillance systems, virtual simulations, and artificial intelligence, we are building a new dream universe that will inform the foundations of the future.”

One thing that struck me in seeing the artists selected for “The Dreamers” was that many of them were of the same (my) generation – with few exceptions, many artists were born in or around the 1980s. Was the generational aspect something you were thinking about in curating the show? Even if it emerged organically, can you comment on why you think that so many works from this generation were resonant with the exhibition’s theme?

It is about a generation of artists that we feel belong to our path, that relate to our own exploration of the world. As we said, these are artists we were raised with, and many of them were published for the first time by CURA. or exhibited for the first time in Italy. CURA. had an important supporting role at the beginning of some of their careers. We were able to juxtapose these artists with Mark Leckey, Pierre Huyghe, Jeremy Deller, and Anri Sala – figures who were essential points of reference to this younger generation – and with very young Serbian artists we encountered during our frequent visits to Belgrade before the pandemic.

You mentioned that the expansion of the subconscious and the world of the dream that we saw with the pandemic took place in virtual space. How do you relate the life of the subconscious to digital experience?

Dreams have always had a predictive role in human existence. Dreams have been a means of questioning the complexity of the world, the great mystery of life, and the inscrutability of the human spirit since ancient times. In The Red Book: Liber Novus, begun in 1913 and written over the course of sixteen years, Carl Jung uses annotations, images, sketches, and notes to describe his own anguished dream projections – hallucinatory visions anticipating a new dark age. Through personal dreams and fantasies, and images perceived in a state of wakefulness and active imagination, Jung seeks to translate the very question of existence – to explain our sense of collective destiny and the primeval images we associate with the multifaceted world of the soul. He sets up a new mythical imagination. In the 1970s, philosopher Jean Baudrillard suggested a third element into the typically dualistic relationship between the realm of dream and the real world – something he calls “hyperreality.” He defines the term as “a set of virtual experiences, which, made increasingly intense by new technology, replace the reality of the external world, shaping the thoughts and behaviors of individuals, but also their imagination and dreams.” In a computational world experienced through machines, technology, algorithms, augmented reality, facial recognition, surveillance systems, virtual simulations, and artificial intelligence, we are building a new dream universe that will inform the foundations of the future.

One leitmotif that struck me among the works in the exhibition was the number of representations of birds. In dream interpretation, birds are generally interpreted positively, as symbols of aspiration, freedom, and so on. If you had to “interpret” the exhibition as a dream itself, what would your analysis be of the symbolism contained in the works on view?

The animal world is one of the central aspects in the iconography of the exhibition. Our relationship with the animal kingdom conjures a feeling of vanished innocence, which places us in front of an unavoidable sense both of loss and of ethical and cultural belonging. “Animals keep visiting us in dreams and remind us of another life, now very far in time and space,” James Hillman writes of this limbo, “in which men had been a species mixed with many others.” Birds play a leading role in this context – something we became aware of during installation, when they began to show up in works by Davide Balula, Nico Vascellari, Alex Israel, Dora Budor, Nenad Gajić, Marianna Simnett, and others. Birds demarcate their territory on the basis of the sounds they make, and therefore speak to us of identity but also of migratory flows, transversality, and passage. In the United States you even have the DREAMers, an act that provides rights and recognition to migrants who came to the US as minors. In a broad sense, for us the migratory flow of birds represents the crossing of geographical, political, cultural, and gender boundaries – all of which the exhibition aims to investigate. Thinking of the dream as a metaphorical space of freedom, in which to reconsider limits, territories, rules, roles, and archetypes, the “dreamers” become the inhabitants of the “passage zone” that Walter Benjamin described as a “threshold,” distinguishing it from the idea of “border.”

The last work for the biennial, Dora Budor’s Plinth (minor key) (2021), was set up only in the last days of the exhibition, but will remain in the park of the Museum of Yugoslavia until its natural deterioration. This work involves bird seeds and other edible material, and is inspired by the architecture of the Museum of Yugoslavia. It is a sculpture called to change over time, to be literally digested, metabolized, dispersed, and re-sowed by the birds in the park. The work speaks of mutability and volatility, deconstruction and regeneration, and questions the ideas of permanence, conservation, and monumentality.

The show moved venues only weeks before the opening, though you never would have known this, given the precision of the installation! A number of works exhibited spoke directly to the context of Belgrade. Others were site-specific, while some were brought in from other contexts. How did you approach the specificities not just of the venues, new and originally planned, but of the city in flux?

The exhibition changed its location three times. In the beginning, when the event was still planned for 2020, it was to take place at the Belgrade City Museum – which is where it actually ended being set up. When it was postponed due to the pandemic, it moved to the Museum of Yugoslavia – which is a very different context, with its modernist architecture, marble floors, and large windows making for many structural obstacles. Many of the works selected required new walls, and the difficulty was to construct a well-thought-out path of rooms – and a coherent relationship between the works – in a completely open 2,000 square meter space. Just a few weeks before the opening in June 2021, the exhibition was postponed again and moved back to the Belgrade City Museum –a very short timeframe for rethinking an exhibition that was, by that time, “set” – at least on paper. Over the course of the intervening year the list of artists had grown, and the projects had changed. We had to start all over from scratch. The artists showed great resilience and a spirit of adaptation given the unpredictable conditions, but we think the charm of the building and its decadent spirit created the right context for the works, sometimes unexpectedly.

Can you comment on works in public spaces, and how they interact critically, socially, or aesthetically with the urban sphere? Belgrade, like many cities, is in a transitional moment – prices are going up, real estate and hospitality investors are speculating on the city, etc. How do you view this and other biennials in terms of their engagement with the evolution of the urban plan and how it is inhabited?

Belgrade is in a time of great changes due to new investments, gentrification, and building speculation. However, the city and its structure are still anchored to old dynamics, to policy that struggles to metabolize its past and has yet to come to terms with history. These structural, political, and organizational relics appear to clash with a city brimming with new energy, with a generation of young people ready to connect with the world, who speak foreign languages, who have traveled, and who want to distance themselves from the recent past. Among the difficulties encountered in off-site projects, which we didn’t realize on the scale we had originally planned, was that the scenario kept changing quickly. For example, Nora Turato’s work should have involved the BIGZ, an abandoned printing house that was, until recently, occupied by artists, students, and so on. A historic Brutalist building and one of the most representative of the city’s architecture, BIGZ was sold a few weeks before the opening and cleared up to become a new hotel. Ebecho Muslimova also had to adapt her project from the wall of a public building to an interior wall of the museum. Aleksandra Domanović, Alex Israel, and Cyprien Gaillard did create public works, with the latter donating a permanent sculpture to the city. A marble bench set up at the crossroads of a very busy pedestrian underpass, it’s a place to stop that’s integrated into its urban context, resonating with the original marble surface of the underpass and a small gem shop not far away. It is nice to leave a permanent mark.

Credits

- Interview: Victoria Camblin

Related Content

Exhibition and Empire: Decolonizing Museums Requires a New “Metabolic” Architecture, Says Curator CLÉMENTINE DELISS

“The Experience We Were Supposed to be Having”: ASAD RAZA on DIY Intimacy, Édouard Glissant, and Home Cooking

Between China and the Arabian peninsula, a “maritime silk road” powers global capitalism – even in the age of the cloud. LALEH KHALILI explains.