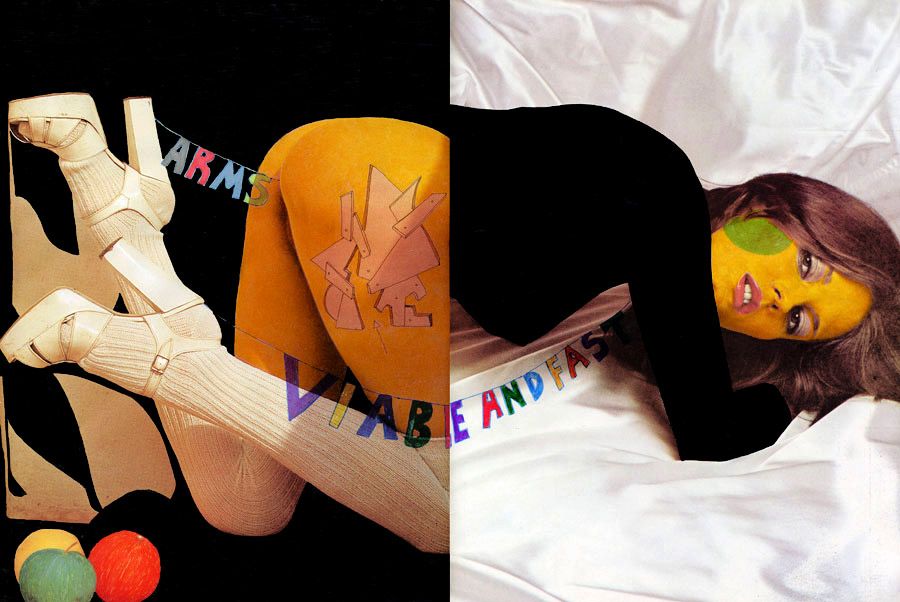

Superstudio & Archizoom 1968–1972

From XIV Milan Triennale to the new domestic landscape: “If design is merely an inducement to consume, then we must reject design.” A portrait of the architectural groups ARCHIZOOM and SUPERSTUDIO.

When students stormed and occupied the XIV Milan Triennale in 1968 before it opened, the end of architectonic modernism was also postponed. Curator Giancarlo de Carlo had gathered his colleagues, the critics of modernism known as Team 10 (Peter and Alison Smithson, Aldo van Eyck, and Shadrach Woods) – for a last appearance together at this exhibition of architecture. The protesting students demanded – with the support of those exhibiting work – a sense of social responsibility from the designers and a farther reaching critique of existing power relations. This somewhat internal clash of critical attitudes led to a radicalization of radical architects, peaking with striking impact in the work of groups of architects critical of capitalism such as Archizoom and Superstudio. Founded in Florence in 1966, Archizoom and Superstudio were intensively continuing the modernist project of the technologization and collectivization of space.

“If design is merely an inducement to consume, then we must reject design; if architecture is merely the codifying of the bourgeois models of ownership and society, then we must reject architecture; if architecture and town planning is merely the formalization of present unjust social divisions, then we must reject town planning and its cities – until all design activities are aimed towards meeting primary needs. Until then design must disappear. We can live without architecture.” (Adolfo Natalini, Superstudio, AA London 1971) This is an exact restatement of the modernist project of design: a functional design meant to serve lives, a design refusing all socio-cultural concerns. It avoids terms of power and authority, because it’s purely technical, because it does not form and tends to transcend itself in its ramifications.

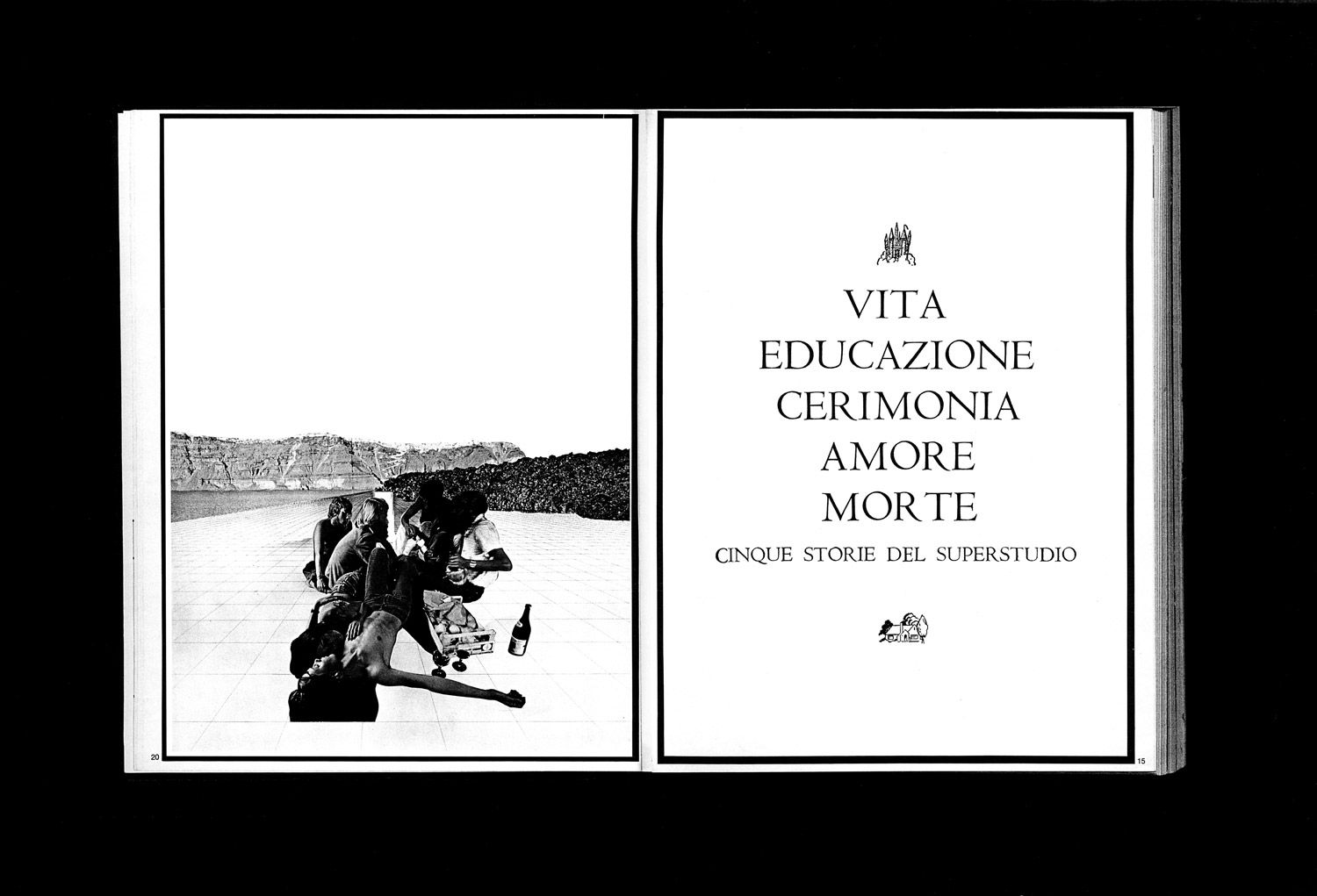

This conception of a complete technologization of the environment, as immaterial as possible, is in line with early modern attempts at functionally mechanizing space. Living in the 1920s was to have become instrumental so that it could make room for a collective living. Built spaces were to have become less important the more optimally they were organized and the more they were relieved of functions, making them more effective for social production and use. Modernism, then, ultimately linked the hope for overcoming competitive capitalism with a cooperative economic system. Technology and collective production would reduce individual work time so that a collective, useful and emancipatory leisure time would ensue. The large machines necessary for this, such as the nursery, the collective kitchen and the centralized vacuum cleaner, appear at Superstudio as the only homogeneous proposed space. With their film project “Superexistence” for the legendary exhibition “The New Domestic Landscape” at the MoMA in New York in 1972, Superstudio illustrated a space of possibility that had overcome all other hierarchical or alienated relations. Along with production, consumption also loses its threat as an extended form of exploitation or reproductive activity. This is also inherent in the project “No-Stop City” in which Archizoom refers to the factory and the supermarket as power-free zones, free of any sort of limitations. The paradisiacal functionalism of the grid and the absence of architecture overcomes all separation and alienation towards an absolutely untroubled freedom of will.

“Architecture must be regarded as a neutral system, available for undifferentiated use, and not as an instrumentality for the organization of society; as a free, equipped area in which it may be possible to perform spontaneous actions of experimentation in individual or collective dwelling.” (Archizoom, in: The New Domestic Landscape, New York 1972).

By JESKO FEZER