Sublime Futurism: ITALO ZUCCHELLI

Happiness may be for the simple minded, but optimism, the American way, has never looked as smart as it does in the hands of ITALO ZUCCHELLI. Six year creative director for CALVIN KLEIN Men’s collection, Zucchelli is known for grafting the infallible promise of technology – the 21st century’s cultural hope – to the fiber of masculine elegance, propelling formal wear light years ahead of sportswear and captivating our futurist imagination in the process. With the silent accuracy of an atomic clock, he is engineering the American man for a new world order, the cool self-realized citizen of emerging global entropy.

Snug. Well cut. Brilliant. A smack-your-lips example of product design, it defines a point of no return in menswear that equates less with the demise of the top hat than the birth of the iPod. In the story you are about to read, nearly everyone had something to say about Calvin Klein underwear, even the bootlegged kind: MoMA PS1 Curator Klaus Biesenbach, for instance, purchased emergency briefs after losing his luggage on a trip to China and “they are still going strong,” he said, 10 years later. Minimal, clear and universally known, they are like the dark slab of Kubrick’s Space Odyssey, a portal to somewhere beyond our tatty reality. Welcome to the tailored universe of Calvin Klein Men.

A collection of six women’s coats and three dresses hand-crafted by Klein and financed by friend Barry Schwartz launched the company in the wake of the 1968 American race riots. (Schwartz had been forced to close a long-standing family grocery business vandalized during the riots and banked his resources on Klein.) Almost immediately, their sober, straight lined women’s wear caused a stir of its own, and some 40 years later the label now appears on everything from soap dishes to backpacks. “Advertising then must tighten the seams and straighten the message to hold on to its power,” says art director Fabien Baron, who continues to coach the company’s image since Klein hired him in 1990. Baron speaks of the brand with brusque affection, like a son he taught to play football or shoot a gun. One imagines that handsome son in a fine tailored suit, perhaps driving a roadster to hear Baron describe the logo: “clean, direct, powerful and beautiful.” He adapted it from its original incarnation, a version of an art deco font called Futura.

Klein’s progressive retirement since Phillips-Van Heusen Corporation purchased the company in 2002 has broadened the brand’s creative vision and, according to Baron, “spread its wings.” He laces the phrase with a good dose of heroism, a drop of regret and something poignantly male: the myth of Icarus. It’s a story of fearless ambitions, braggadocio and flying to the sun. Unlike any other brand that dominates the global billboards of fashion in the same way, Calvin Klein has presented a distinctly male identity across all its products, “outing” a modern Olympian fantasy. Paris-based sound designer Frederic Sanchez, who has created the sound of Calvin Klein shows for the last 16 years, says the brand’s audio signature “is always something very masculine, controversial, minimal, simple and direct.” Beyond the spread of new men’s fashion rags, growing menswear revenues, and greater assimilation of male customers into the larger fashion system, the Calvin Klein identity sets an ideal stage for modern menswear. If fashion historian Anne Hollander is correct, that “Male dress was always essentially more advanced than female dress throughout fashion history, and tended to lead the way, to set the standard, to make aesthetic propositions to which female fashion responded,” then menswear is the future and the Calvin Klein man is like modernity to the second degree, our escort on the red carpet to a distant horizon.

Italo Zucchelli, an Italian-born designer picked by Mr. Klein, has directed the brand’s Men’s Collection since 2004. I dress as a man, and from this perspective, fashion seems more of a problem than a pastime, a frankly stiffer medium of self-expression than it has been for women. Zucchelli on the other hand doesn’t seem to shoulder any grudges. He wears New Balance sneakers as pleasantly as his Buddha-like face. Nian Fish, 18-year veteran of the KCD production agency and now an independent creative director, tells me, “People don’t get stressed around Italo because you ride his wave of being present and in the moment. He is very light.” Biesenbach, a friend, adds, “He is so modest and at the same time very precise – a rare quality.” True enough, meeting Zucchelli was light, clear and precise like the tubular steel armchair that graces his living room, a signature Starck design of 1983. A large-scale print of model David Agbodji’s naked back, a molten monolith from Calvin Klein’s Spring and Fall 2010 campaigns sits close. More effusive than his portrait let on, Agbodji later confided: “Italo is probably the nicest, down to earth person I know in this business. Working with him greatly changed my own style. I had no clue how much I love modern minimalism until him.” Zucchelli invited me to sit at a comfortable distance from the overpowering photo. I hoped to learn a lesson similar to Agbodji’s, to understand Zucchelli’s world and philosophy of menswear. We sank into a soft gray couch that frames the view of midtown from his penthouse apartment. Reflecting on a skyline built of testosterone, I asked, “Should a man dress to show his power?” “A man should dress to show who he is,” Zucchelli replied. His tautology dispelled any hopes I had of borrowing an identity from anyone or anything outside myself.

“And if the people stare/Then the people stare/Oh, I really don’t know and I really don’t care.” Zucchelli owns a T-shirt printed with these lyrics, excerpted from a Smiths’ song called “Hand in Glove” and printed in fluorescent red. Buoyed by a plaintive harmonica, Morrissey delivers a kind of rebellious, sexually charged, romantically hopeful call to arms. This 1983 release was Zucchelli’s introduction to the band, along with a cover that reproduced an image by West Coast beefcake photographer Jim French. The cover shows a naked man on a blank wall, leaning into the light, printed in a bright monochromatic blue. Around the same time, Zucchelli discovered Calvin Klein: “I saw Bruce Weber’s underwear campaign with Tom Hintnaus (1982–83) in L’Uomo Vogue. It represented a man with an amazing body, on a white background, under a blue sky. To me, it was quintessentially American, very fresh and athletic. Nobody did underwear campaigns like that then. I was 16 or 17. It was very new and that’s how I’ve seen Calvin Klein ever since.” Frederic Sanchez, who says he strongly associates the brand with the muscular work of Robert Mapplethorpe, remembers the ads plastered everywhere he looked: “It was an idea of America like the one you might get from reading GQ in the 80s, or Andy Warhol’s Interview. I thought any brand that has this kind of serial imagery has channeled the power of Warhol. None of it was very innocent, but that’s what made it so interesting, and all this before Madonna.” The 80s man was big, beautiful, healthy and out to shine like the sun. A Bruce Weber editorial for GQ from 1980 of men in electric and revealing sportswear says it all: “Clarity. Logic. Ease of wear. That’s fashion’s attitude for the 80s’ first spring. And you? Color. Energy. A smoothly functioning body. That’s your self-image. Strength. Self-reliance. No delusions.” There was no need to continue hiding in dark gyms, darker discos, poolrooms and swingers’ bars. Confidently facing the future, and the critics, the sun shone out of their behinds, or so sang Morrissey.

Photographer Ryan McGinley, who knows something about the celestial glow of bodies, first met Zucchelli while wearing the Smiths’ lyrics T-shirt. McGinley invited the designer to his 2010 exhibition “Everybody Knows This is Nowhere,” but had tracked his evolution at Calvin Klein from the start. McGinley wears Zucchelli’s suits “religiously” and never misses a show: “I‘m so excited for new designs each season. Italo understands the type of clothes men want. He’s making necessary pieces that have become a staple in my wardrobe.” Zucchelli responds to the youth, freedom and rawness in McGinley’s images and not surprisingly, the photographer returns equal admiration for Calvin Klein advertising. He argues that under Zucchelli, Calvin Klein continues the captivating legacy initiated by Weber and Avedon, “placing models within minimal backdrops that force the viewer to focus on the clothes and pay attention to the subtle details of gesture and clothing,” techniques, the photographer says, he uses in his own work. Yet, McGinley takes his images a step further. He eliminates accessories, gadgets, furniture, vehicles and cities, along with clothes, until all that remains is what clings to the bones, specimens of youth in an Edenic “nowhere” purified of consumer trash and distractions, a manifest subject made real again.

The most compelling images from Zucchelli’s advertising campaigns over the last eight seasons, shot by the likes of Fabien Baron, David Sims, Steven Klein and most recently Mert and Marcus, perform a similar purification. They emphasize the person before the lens. While Weber’s famous image of Hintnaus, along with other more abstract compositions shot through the 80s could seem handsome but generic, the company also generated images of men who appeal through personality, like Robert lannucci, Sasha Mitchell, Kelly Rippy and of course Marky Mark, to name a few. For Zucchelli the model is central to every collection. “In theatre you cast the actors to portray the play. In fashion, for Italo, it’s built on character and in this case it’s the model,” explains Nian Fish, who produces every element of the runway event, down to finding the manicurist. Casting for a Calvin Klein show begins four months in advance and after a handful of models are selected from a vast pool to be exclusively signed to the brand, an even smaller selection will try on the collection. One or two become the “muse” coalescing the final looks that appear on the runway and eventually posing for the ad campaign. “A lot of people don’t do this,” Fish says. “Picking the exclusive person to build the vision of a particular season is left over from the Calvin Klein days.”

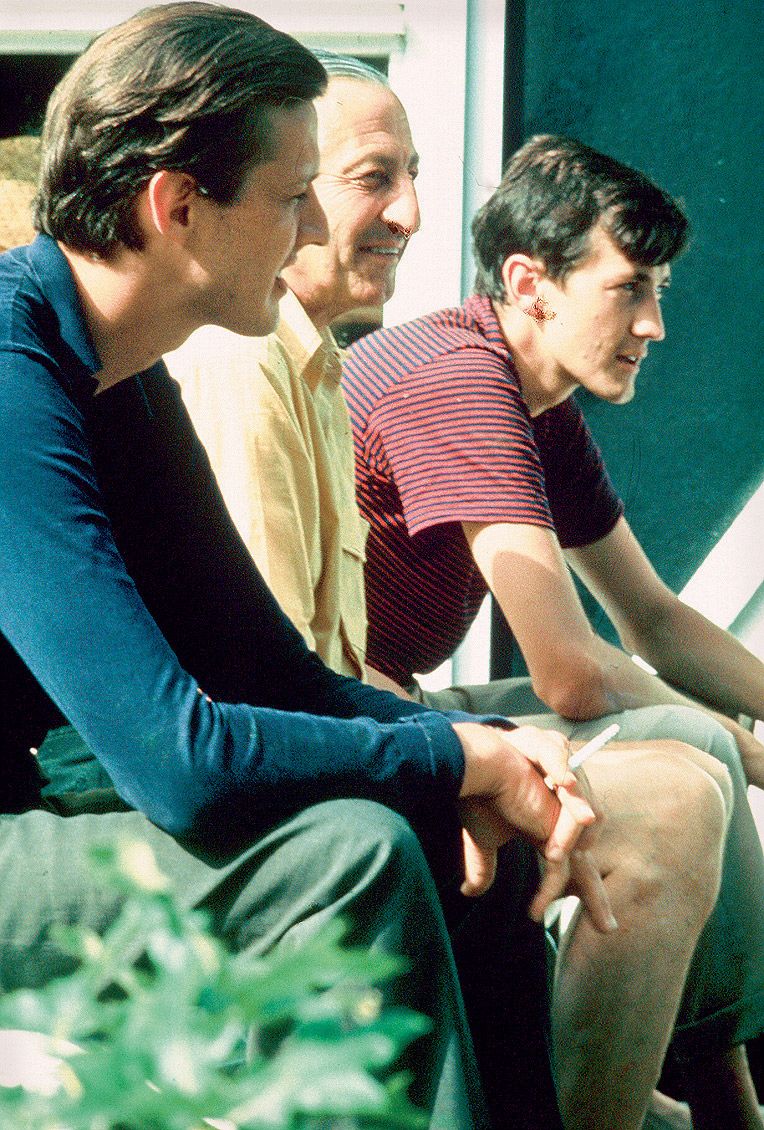

Zucchelli keeps a constant reminder of American “realness” in his corner office, a portrait of bulging bare-chested Marlon Brando posing as Stanley Kowalski from the 1951 movie A Street Car Named Desire.

Often, Zucchelli’s muses are rookies who have never seen a runway. While Mrs. Fish and her team train them, she stresses: “The model’s personality is really important. They have to be switched on, because when they walk out of their changing room, they have to ‘sell’ the outfit.” She admits having had models that are “dead behind the eyes and it just doesn’t work.” None of Zucchelli’s recent stars like Sean O’Pry, Bev Moore, AJ Abualrub or Dmitriy Tanner, who has been Zucchelli’s focus in the last collections, are easy to stare down. Each one is a mix of tough guy and kouros, their stare packs a punch, hand in glove. This is particularly true of David Agbodji, who as a black model faces one of the fashion world’s most backward prejudices. He opened the Spring 2010 show, a breakthrough according to Fish, and his image landed superhuman campaign billboards. Agbodji’s experience on the runway speaks volumes about Zucchelli’s Calvin Klein man: “I never felt as confident walking down any other runway,” he says, adding that the clothes are bold, but not the kind that “would look amusing in the street. It’s real life boldness and I think that’s the genius of Italo and his team!”

Editors and retailers alike appreciate Zucchelli’s no-nonsense focus. Reporter Eric Wilson from the New York Times explains: “He tends to start with a clean line that’s very accessible and adds elements that are more challenging and unusual, but always in a way that a customer can relate to. Italo keeps in mind that he is designing for men and not women, that there is a real world outside the bubble of fashion insiders. It’s a big mistake that a lot of designers make, especially the Europeans.” Zucchelli keeps a constant reminder of American “realness” in his corner office, a portrait of bulging bare-chested Marlon Brando posing as Stanley Kowalski from the 1951 movie A Street Car Named Desire. Zucchelli has never removed his vintage paperback copy of Tennessee William’s play from its cellophane slip, as if to contain the power of its iconic cover model. Idols like Brando or James Dean served as widely accepted prototypes of masculine style, especially in the way they galvanized a generation of casual dressers (T-shirts and jeans), but was it them or the characters they played? Is Zucchelli thinking of Brando or Kowalski, or both? David Agbodji, for example, defined the Calvin Klein man like this: “extremely confident and fearless, strong, in great shape and super duper confident. Classic American superheroes like Bruce Wayne or Superman come to mind.” But, how real is Superman? He may be more real than you think. The image of “real men,” particularly in American culture, combines fiction and fact to a degree where the two are inseparable, indistinguishable even.

ITALO ZUCCHELLI: When I do a collection I think about the things men would want to wear. On the other hand, when I do a fashion show I have to create a fantasy. My ideal is to reach a perfect balance. It’s like a perfect pop song. It is the most difficult thing to achieve for an artist: to create something that may not seem commercial, expressing his or her creativity to the fullest, and then to see it become a commercial success. Kate Bush’s first single “Wuthering Heights” comes to mind. She was 19 and she sang a song that in 1978 was not what the radio would play – just a girl with a piano and a voice. She fought to release it as her first single (her record company favored another song). It made her a star immediately, number one all over Europe. It was the perfect combination of creativity and commercial success and it’s very inspiring.

PIERRE ALEXANDRE DE LOOZ: Perhaps the consumer we think exists is just a fantasy?

I recently read that Steve Jobs avoided focus groups. He believed you have to show people what they want and he proved it. The iPod is a great example. I obsess over music and to me it was revolutionary; a minimal and perfectly designed object that everybody uses, and the most commercially successful product of the last decade. Jobs was incredibly clever and intuitive. I’m fascinated by the fact he applied Zen principles in his “creative strategy” and the result was pure innovation.

“And if the people stare/

Then the people stare/

Oh, I really don’t know

and I really don’t care.”

How do you use intuition?

Without comparing myself to Jobs, I’ll give you an example. I wanted to use neon color for a while. I debated whether it was chic enough and the many ways to use it. Suddenly, in a vintage store in LA, I saw a wet suit with perfect neon colors. I thought it was a message and decided it was the right time. I assumed the fluorescent suits would simply be an editorial piece, but they did not even arrive in stores – people bought them over the phone! There was clapping in the middle of the show – it was a real moment.

How do you keep your intuitions fresh?

Transcendental meditation. Intuition is something everybody has and meditation is a great way to develop it. I was given a mantra 20 years ago. I sit down and close my eyes, repeating the mantra for 20 minutes. It’s a tool. I would do it even if I cultivated tomatoes because I love it!

What defines the style of American men?

On an elemental level there is a casual, less conceptual or philosophical way of living in America. American men have been trained to take good care of their bodies, practicing a sport or working out at the gym. It’s very different from Europe.

It’s an obvious exception to the distinction you just made, but what do you think of Versace’s menswear from the 90s, since his men were on an American scale?

I thought it was fantastic. It was the opposite of what was going on and it marked the moment of Versace’s career when he enjoyed his greatest success. Sadly, he died shortly after. I see the 90s as a reaction to the 80s, which were about flamboyance and excess. You could design anything, even skirts for men. It would sell and people would wear it. Then came the Gulf War and we entered a major recession. Fashion in the 90s turned to purity. It was almost “non-design” – the opposite of 80s maximalism. But then, Versace became even more baroque. He was making people dream in sad times, you might say. Did I wear it? No, it wasn’t for me. But, it was fun. He invented the super models. He worked with Bruce Weber and Avedon. He created the kind of excitement that fashion always needs.

If the Calvin Klein identity were ever to part ways with minimalism, it will have taken a radical turn; yet, you seem to flirt with the possibility. Do you ever let yourself be kitschy?

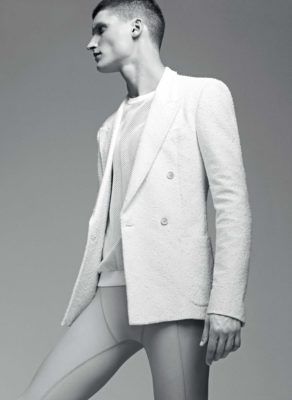

In a sort of minimal way, I actually did for one of my earliest runway shows (Spring 2007). The aesthetic was clean, of course, but I sent some models down the runway with leggings (I don’t think anybody got it, but I pretended they were the kind of swimsuit worn by Australian surfers.) When the first of the legging models came off the runway he said, “I think I caused a stir!” That was the show where everything changed: people gasped. It was borderline underwear, borderline kitsch without having to do skirts or brocade. I had taken a staple of American sportswear and combined it with the sex value of the Calvin Klein brand. One reviewer said that you could see whether the models were circumcised or not! A lot of people laughed and some didn’t like it at all, but you need these moments! The midriff T-shirt (Spring 2011) was also very risqué. In eight years it was the most photographed item I’ve designed!

You sexualized the man but did you also feminize him?

Androgyny as a concept was one of the things that drew me the most to the brand because I was always fascinated by it, but especially androgynous women. That’s why I love Tilda Swinton, Annie Lennox, and Grace Jones. David Bowie is on the other side. In fact, I hope Tilda Swinton will play David Bowie in a movie someday. She would be perfection in the role, not least because she is playing a man. There is something extremely modern about the genders coming together, or men and women who dress alike. Calvin always played with that. Even Kate Moss was a creature in the beginning. She was a girl but also otherworldly. That’s the power of unisex. I grew up with this fascination. Even if I am unaware of it, this attitude will come out of what I do from deep inside my imagination.

But you grew up in a country where the gender roles are so clear?

That’s probably why I was fascinated with the middle, as a rebellion.

Are you familiar with Fellini’s sketches where he imagines a muscle woman whose clitoris stands erect like a penis? Modern androgyny was probably invented in Italy.

The Park Hyatt in Tokyo has those drawings on display! It’s an ancient tradition, but that’s where we are headed. The future will be less worried about gender and it will be reflected in clothes.

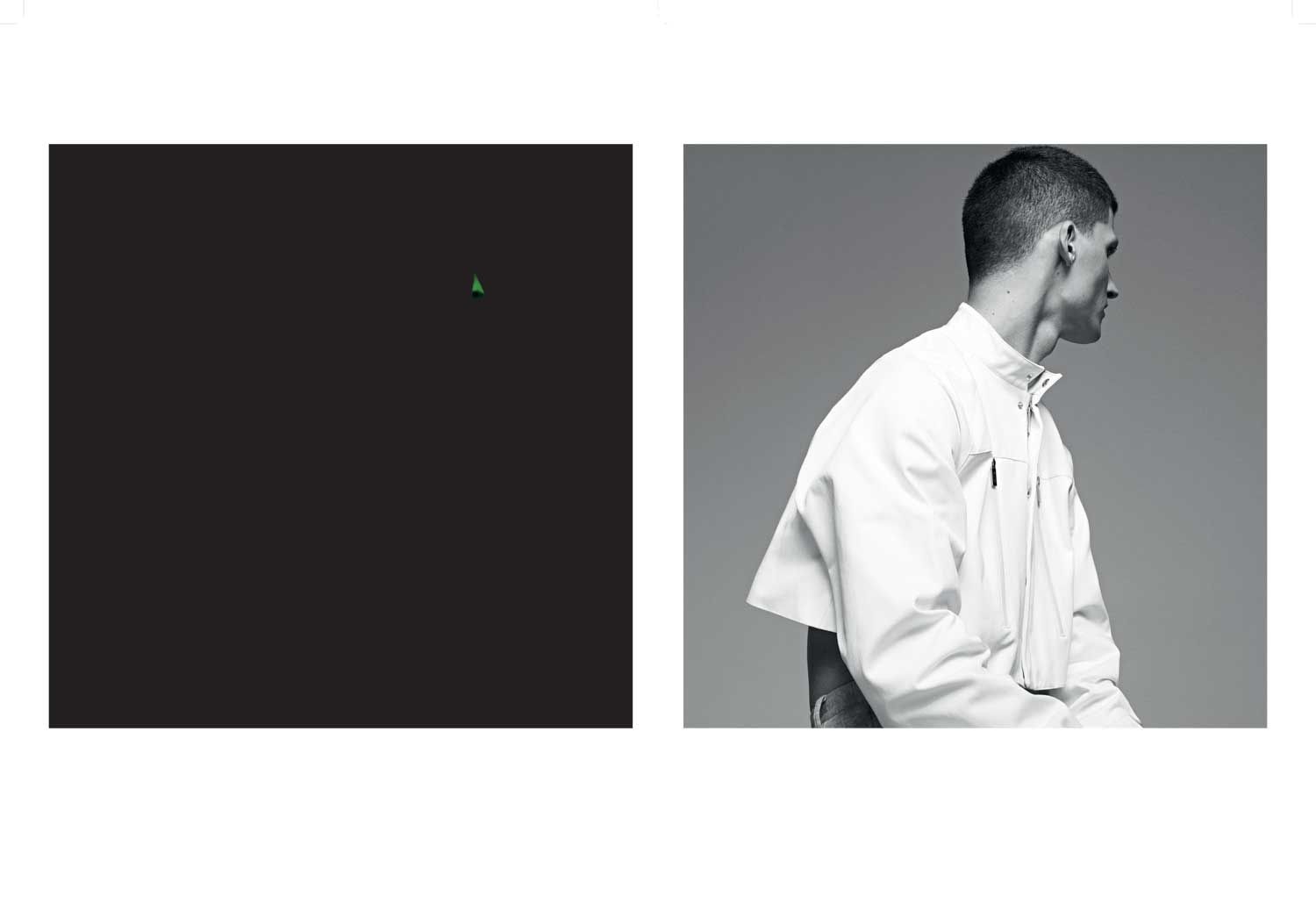

You are nudging us there! Your collections could be described as a battle between the T-shirt, which is increasingly genderless, and the man’s collar shirt. Lately, the traditional men’s shirt seems to be losing.

Lately, it’s true. T-shirts are very American; just think of James Dean! I was not born here, so I fantasize about the American look – again, we go back to the fashion fantasy. How do I make menswear look relevant and iconic but at the same time highly designed? The T-shirt is the number one staple of American sportswear and the American identity.

Nevertheless you’ve manipulated the traditional shirt. Would you call that fashion in its truest sense – because you are making small changes to a prototype, and these changes can cycle from season to season – or is this what we call progress?

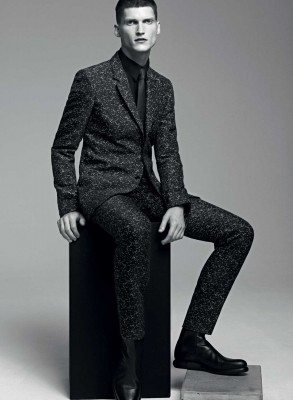

To achieve any results in fashion, it takes time; that’s why I have three fittings in my process. Every collection starts from what you achieved in the last one. Menswear elements like the suit are subtle, whereas sportswear can be extreme and bolder and it’s easier to update. In menswear you have more rules and fewer elements than in women’s fashion, which I like. I find it more challenging to achieve something new while staying within the rules, or, you might say, breaking but not destroying the rules.

Hindsight shows us moments when contemporary fashion reached decisive points, like the little black dress or pantyhose. Do you have any inkling what the next major step for menswear will be?

When Chanel did the little black dress, fashion as we know it was at its beginning. She was a genius, but she arrived at a point when women were still wearing frocks. She simplified the woman. When Giorgio Armani put women in suits, that was genius and both times fashion was still young. These kinds of avenues have been well explored. I am not sure a statement as vast could be made now. My biggest fantasy for the future is that we’ll be able to disappear and not even need clothes. When we live on spaceships, maybe then someone will come up with something as groundbreaking as Chanel.

So, the revolution will come from life and fashion will respond. Thinking back over the last 60 years, who together with Armani has shaped menswear to modern life?

Armani created the power suit for both men and women and empowered women to be as powerful as men. He also created a whole new language, still very relevant today, for men in business and for celebrities – think of Richard Gere in American Gigolo. He created an effortless, everyday man that lives in a modern world, unfussy and real. He always speaks about sobriety. That is his mantra. His company is 30 years old this year, but something so good doesn’t have an expiration date. Helmut Lang created something very sleek, street cool and desirable, especially for men. He defined an era and it was a big loss when he retired. I wore a lot of his clothes because they fit me so well – like a reflective pair of pants!

What other American designers besides Calvin Klein attracted your attention?

Stephen Sprouse was the only alternative designer in America that I was interested in as a student. I never wore anything by him, but I know his vintage is hard to find, and expensive. The fluorescent colors, graphics, graffiti and punkiness; everything about it was underground.

In a similar way, Hedi Slimane has been recognized as having applied countercultural references to men’s tailoring. How do you describe his contribution?

He brought back youth culture. He influenced fashion through the shape he created – a skinny idealistic guy – which was androgynous in a way. All his muses are very young. I relate to his music interests and his interest in the underground, which is where everything comes from.

In the Wim Wenders movie A Notebook on Cities and Clothes from 1989, you see Yohji Yamamoto explaining his love of August Sander’s photographs. They are predominantly images of early 20th century working class men whose clothes are loosely fitted. It reveals a secret code of fashion: if something fits perfectly, it looks tailored and non-proletarian. You are clearly obsessed with precision, so what does looseness mean to you, and how do you use it?

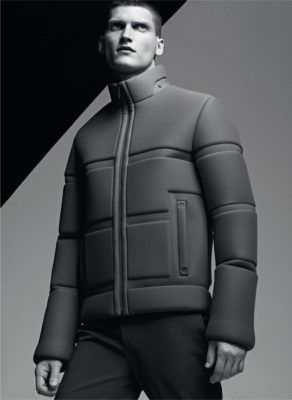

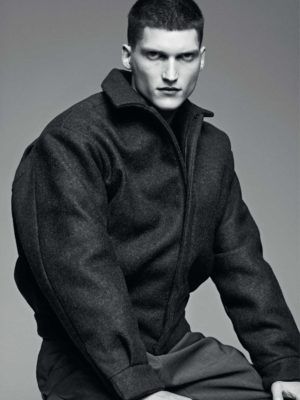

I recently started doing over-sized shapes – let’s use that word – in sports- wear. For Fall 2011 I did a bomber and I wanted to make the classic bomber even rounder, to emphasize the iconic. Yamamoto is a master and Japanese fashion has been over-sized since the beginning. But, I would never do this with a suit.

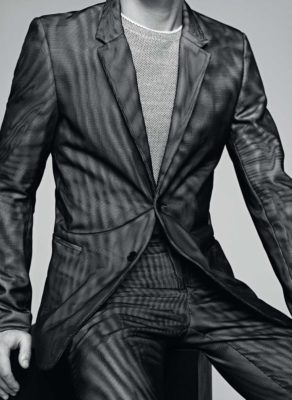

A honeyed accent doesn’t give away Zucchelli’s heritage as much as his ability to cut a jacket. A Wagnerian sense of color and experimental materials reveal professional stints with both Romeo Gigli and Jil Sander respectively. He may seem of a piece with European contemporaries like Prada or Raf Simons, but critic and friend Tim Blanks argues that Zucchelli is refining an entirely personal viewpoint, what he calls “subtle futurism,” an evolution sewn discreetly into every collection. Stitch by stitch it could add up to an altogether altered reality.

Everyone agrees Zucchelli has stepped into a big pair of shoes – a pair of Calvin’s as it were. He’s won respect for not kicking them off, but Zucchelli notes the paradox faced by a generation of talented designers who, like him, are breathing new life into old brands: “If all of us were strictly referential we would be criticized. It’s very important to respect the language and understand the staples, but also evolve because time moves on.” With nearly two decades of witnessing audience reactions to every twist, fold and turn on the runway, Nian Fish warns that the pressure to innovate is ruthless: “If you are safe, they will kill you.” In her opinion, Zucchelli is moving not only the clothes, but also the whole brand forward. Forward? Fashion may innovate, but certainly not in the same way as technology, or does it?

It’s a common perception that men’s fashion is slow to change, and Zucchelli acknowledges that: “Few men will respond to a fantasy as freely as a woman.” However, he observes that many more men are interested in fashion today than a decade ago. In numbers alone, international consumption of men’s apparel and accessories had nearly caught up to women’s by 2000, and with increased freedom of choice. In the years that preceded Zucchelli’s arrival at Calvin Klein, innovative menswear seems to have been largely defined by flashy changes in shape. New York Times reporter Eric Wilson recalls: “Thom Brown created the shrunken suit, Hedi Slimane the extremely fitted suit and Tom Ford the louche, high-waisted big lapel suit. They were contrasting looks but they worked all at the same time, making menswear feel very exciting all of a sudden.” Currently, Wilson believes, a band of niche designers has splintered menswear center stage leaving no clear headliner. Things are set for a major voice to rise. So the question facing Zucchelli, as Nian Fish puts it, “is how far to push without the shock of pushing too far.”

Are you ready? Cotton and metal weaves (2006); nylon moirés and PVC packaged wool (2007); silver PVC and mesh covered neoprene (2008); reflective wool and liquid twill; stretch, heat-bonded, debossed and molded foam wrapped in wool and nylon; punched and bonded paper-based fabric (2009); bark-texture coated cotton and heat-bonded Mylar; transparent nylon (2010); laminated nylon pile (2011); laser cut mesh cotton, resin suede bonded jersey (2012). Perhaps more than anyone in the field of luxury menswear, Zucchelli manipulates the genetic code of clothes, merging natural with synthetic materials as if engineering a sneaker, a car or the wardrobe of a Hollywood cyborg. Zucchelli’s laboratory, a modest fluorescent-lit space with a discolored concrete floor, emerges from down a blaring all-white corridor in Calvin Klein’s 7th Avenue headquarters. The other surfaces are plastic laminate, the most ubiquitous and virtual of today’s architectural finishes, and they are pitch black. The contrast ignites my eyes. Everything looks sharp, most notably a few well-chosen crystals Zucchelli keeps by his desk. “The next time you are on the beach, pick up a grain of sand: that is a quartz crystal,” he says, explaining his fascination. “They are beautiful to look at and they have been used since the dawn of civilization. Our telecommunications system, like computers and telephones, is silicon-quartz based. Crystals have a ‘connecting’ power with other worlds or dimensions.”

Similarly, Zucchelli strives for higher-order connections in his working process. He almost never sits in his corner office, but prefers to share the open studio space with his five-person team listening to atmospheric and “mental” music. He favors small, well-appointed groups of “very good people that are happy and engaged.” Together they initiate every collection, which can include upwards of 40 pieces, by travelling, either to Los Angeles, London, Tokyo or Berlin on a scavenger hunt for books, magazines, vintage clothing and, most of all, ideas. At the moment I find myself looking at meticulous, hand-drawn sketches and material swatches the team is preparing for the Fall 2012 debut show in Milan.

+++

I start every collection early. Nobody starts as early as I do. This is a system I inherited from Calvin. I never abandoned it because there is an ocean between us and where the clothes are produced. During the six-month process I get three fittings, which is a lot. It’s good. I can perfect things. The core concept I come up with now is what you are going to see in January. I say it because it has always been like that – that’s what I do.

What did you learn from working with Calvin Klein in the beginning?

I worked with him for three years and it was an amazing relationship. He always knew if he liked something or not. He solved things without compromise. I am similar in that sense. He was very quick. He made decisions almost immediately, which is very American. Europeans can be philosophical about things, but these are clothes! His response was very good, it was the main thing that allowed me to go in one direction or the other and then apply my European sense to make it the best possible. I learned the immediacy from him. I never heard him say, “I don’t know” … ever.

You never doubt yourself?

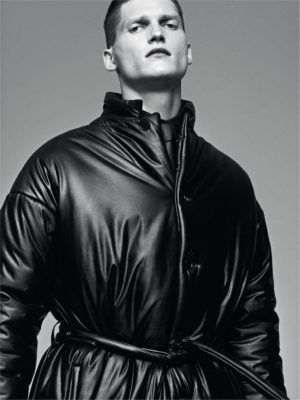

No I don’t. I question myself but not in that way. Last January the concept for the show was “protection” and I came up with it in August. Then we perfected the concept until the end.

Didn’t you tell me you have a German bent?

I joke about it.

You are being conceptually rigorous because you identify an idea and you stick with it. In other words, if I look at any collection, everything I see refers back to the exact concept you came up with in the beginning?

On the runway it is definitely the case. When you do a show the message should be self-explanatory. It’s important to express the vibe of it very clearly. Often it is verbalized at the beginning, but it can also happen towards the end. It helps the team to communicate and work together, and convey the construction of a mood.

To give it a name is to make it recognizable to everybody else, like the public and the press. Do you ever let yourself use more than a single word?

Yes, but I prefer one. I think it’s more powerful. I also like journalists who do their job when they see a show. I give them a word and they elaborate on it.

Is the person who wears your clothes American?

The world we live in now is global. People take planes the way we took buses 20 years ago. Of course different markets have different requirements. What I design is produced the same for every country, but retailers in each area purchase different elements, based on what they think they can sell. What you see in a runway show is only a third of what compromises a complete collection and the rest appears in the showroom for the buyers. The show gives a message to the journalists. The buyers however see the depth of collection in the showroom. The presentation is an edit and we aim for consistency. I could do a show where every outfit is different but it would be completely wrong and the press would get confused. You have to meet commercial needs.

So how do you keep your audience interested?

Instead of giving you a flannel blazer, which will always be in the collection, I might use a fabric that looks like flannel from afar but in reality it’s a techno-fabric mixing black and white; it’s a texture and it’s nylon; it doesn’t crease and it makes you look very sharp and modern. For Fall 2008 I used a thermo-fabric that loses color based on body heat. On the runway, the material gave off an impression of the model’s chest. These special effects are made to look effortless and it’s a way of updating familiar clothes.

As a matter of fact, some of your designs would not look out of place on a CG character like the T1000 Terminator. What kind of special effects, to use the term loosely, do you think men are prepared to wear today that they would not have accepted so easily in the past?

Men want more color. They do plastic surgery, use facial products, exfoliate and hydrate. I don’t think men will be wearing lipstick, but men’s make-up will become mainstream.

What are the most technologically challenging pieces you’ve ever created?

We created a Mylar suit, although it’s not really a fabric, for Fall 2010. The concept of that collection was protection and Mylar, which is used for marathon blankets, is very thin, light and insulating. It also has great texture and nothing else quite gives you that effect. Mylar is only produced in silver, so we found an American manufacturer who could print color on the material. When we started making the pieces, which were heat-bonded, we found that the color would melt and fade in the heat, so we had to start over. We learned we had to face it with a protective layer. It was a whole process that took three or four months to develop and the manufacturer doesn’t speed up just because you have a fashion show! We managed to include the pieces in the show and they looked great on the runway, but it was very challenging. These types of pieces are very specific and are not necessarily bestsellers, but the Mylar suits actually went into production and were well photographed.

Zucchelli disavows any intention of being futuristic with his experimental materials, as when rapper Kanye West suggested the designer had snatched a jacket from the sci-fi movie Tron. That wouldn’t be real. “The way he confidently mixes the familiar and the utterly alien is Italo’s most seductive signature,” argues Tim Banks. Zucchelli’s futurism, if it exists, honors man before machine. Less of an ideologue than some of his peers, Zucchelli treats fashion like a humanist. “Fabrics are the soul of the clothes,” he tells me, which may be why he is riding a deeper and longer wavelength. Longtime New York editor, creative director and statesman of style Glenn O’Brien, who has consulted for Calvin Klein over the years, noted: “We are at a weird moment when people are almost wearing costumes rather than clothing. Maybe they feel alienated; they don’t feel authentic or feel they have a defined role. I think that’s why we see a lot of tattoos and ordinary piercing and stuff. I think it’s a quest for something that’s missing.” We talked about the beauty of tuxedos over the phone, as he took a break from building shelves in his basement. “By putting everybody in the same thing, instead of making everybody look alike, you focus on what’s different about them.” In his recently published, dashingly perceptive style guide How to be a Man, O’Brien launches into an eerily topical rant about corrupt and paralyzed democracies and boldly concludes that “It’s time for a revolution based on menswear,” and “a suit that the corporate suits won’t look good in.” What if O’Brien was addressing Occupy Wall Street, which the American press has struggled to decipher, making accusations of what one reporter called “a branding problem”? What if, I wonder, every last one of us wore suits to the revolution, what then? As much as the melodramatics of fashion may betray certain realities, from our changing perceptions of selfhood to global systems of production, it can also waylay our clear judgment. Fashion, O’Brien seems to suggest, should not be underestimated, an unavoidable form of modern consciousness that also needs focusing and healing, especially now. Zucchelli’s measured, meditative and stealth futurism seems entirely apt, fashion’s Deepak Chopra rising.

What’s your advice for my fashion well-being?

Be yourself is the golden rule. It is very important to choose clothes that represent your personality. Choosing clothes is one of the most powerful ways to express who you are. You should wear the clothes and not the other way around. You also can’t look in the mirror for hours or be too analytical and obsessive about being perfect, because it will feel and look contrived, especially in a man. That’s what’s strong about the American fashion spirit and why sportswear was invented here. It is casual, less studied and spontaneous. That language really speaks to me because that’s how I choose and wear clothes myself. I almost never look at myself in the mirror.

+++

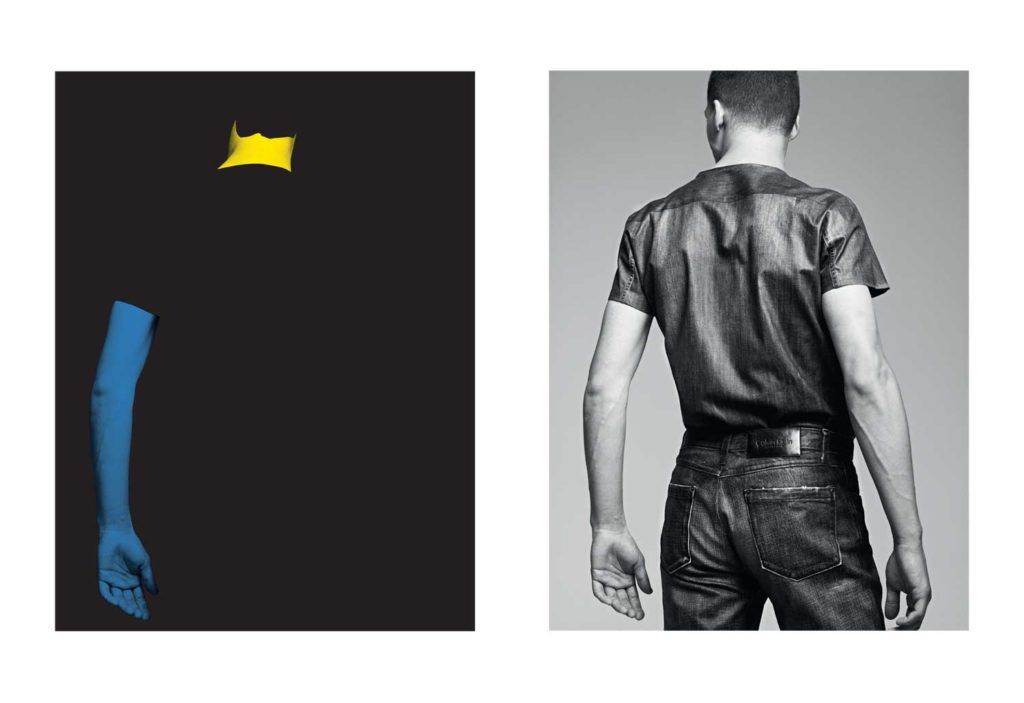

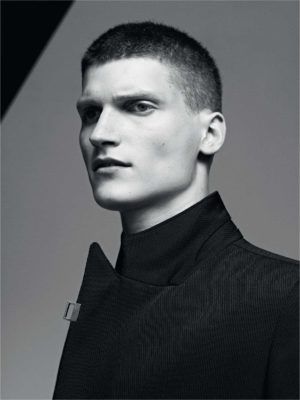

Photography KARIM SADLI

Fashion ITALO ZUCCHELLI

Model JAKUB@The Right Stuff Management

Hair KARIN BIGLER using Aveda; D&V Make up HELENE VANNIER@Artlist Paris; Casting KARIM SADLI; Photo Assistant ANTONI CIUFO and JULIA CHAMPEAU; Digital Operator EDOUARD MALFETTES@Digit Art; Production JULIE BERTON@Artlist Paris; Shot at DAYLIGHT STUDIOS PARIS

By PIERRE ALEXANDRE de LOOZ, Photography by KARIM SADLI, Portraits by ROBI RODRIGUEZ