SISTER CORITA

|NICK CURRIE

SISTER CORITA wasn’t – and therefore was – made for worldly fame.

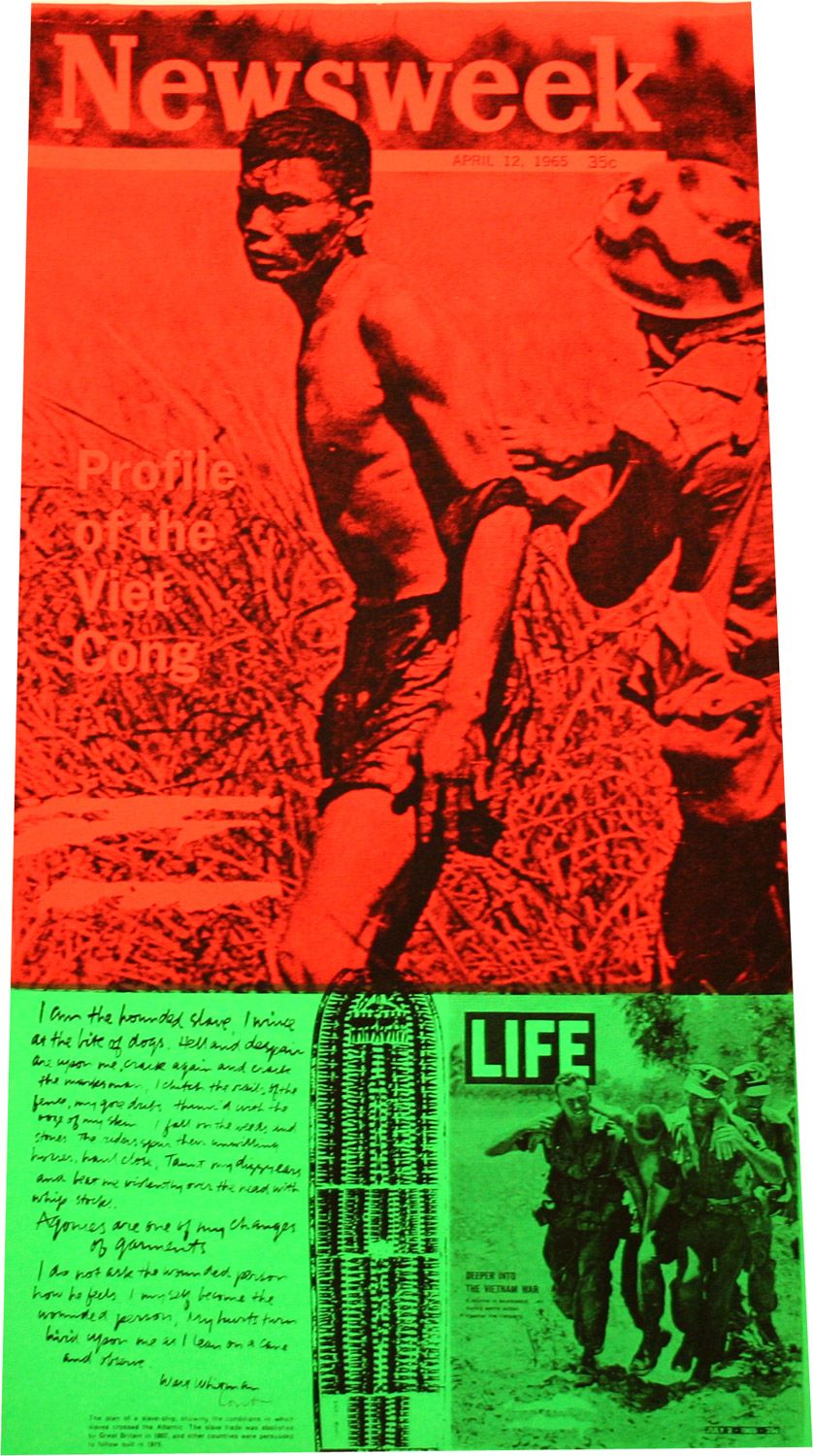

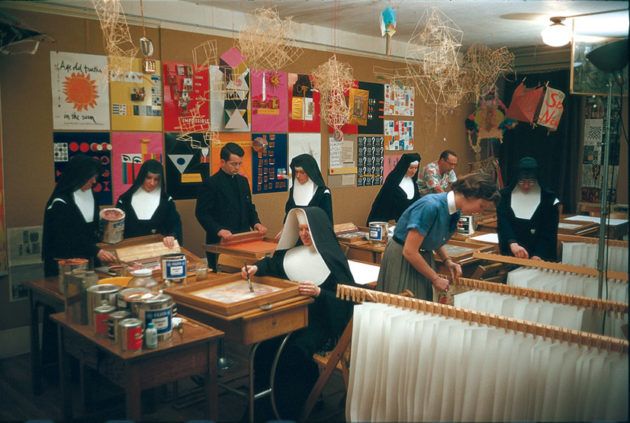

Who’d have thought a middle-aged nun would make pop art serigraphs, appear on the cover of Newsweek, design a “Love” stamp with a print run of 700 million, make the world’s largest copyrighted artwork (some splashy brushstrokes on the side of a Boston gas tank in which some claimed they could see the profile of Ho Chi Minh), befriend Charles and Ray Eames and Buckminster Fuller, promote peace, and be forced out of her seminary after crossing swords with a conservative archbishop?

And who’d have thought that the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart seminary would, just a year after Sister Corita’s departure, collapse and be disowned by the Catholic church because many of the nuns – following a series of encounter groups organized by the humanist psychotherapist Carl Rogers – embraced lesbianism? The desublimated sixties were a weird and wonderful time.

In a way, Sister Corita’s art is overshadowed by that historical moment when “permissiveness”and“old-fashioned virtue” still knew where they stood, and when it was therefore still possible to shock and surprise people. Twelve years after her death – perhaps precisely because we live in such different times – the art nun is experiencing a sort of renaissance, being championed by people like Wolfgang Tillmans and Aaron Rose.

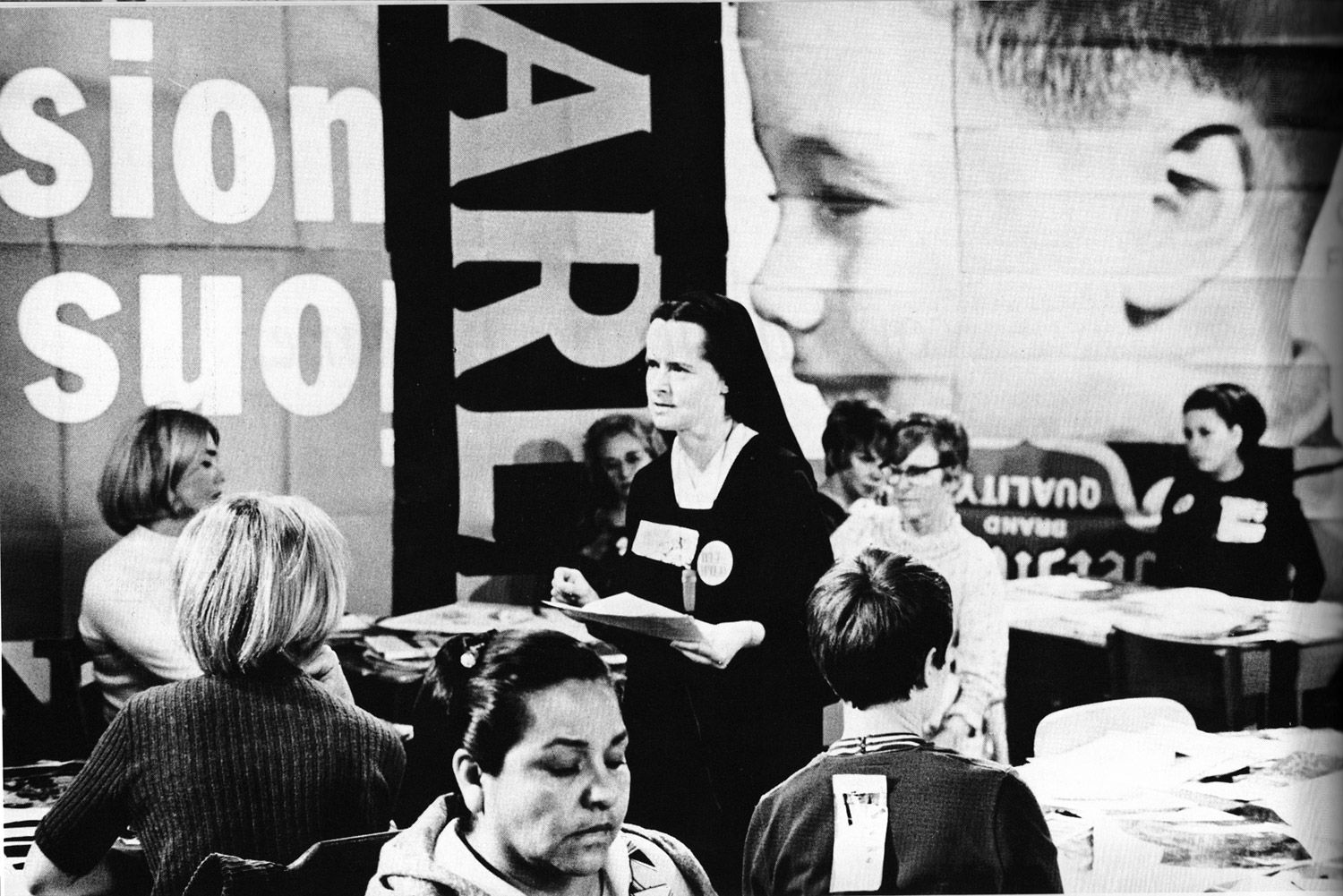

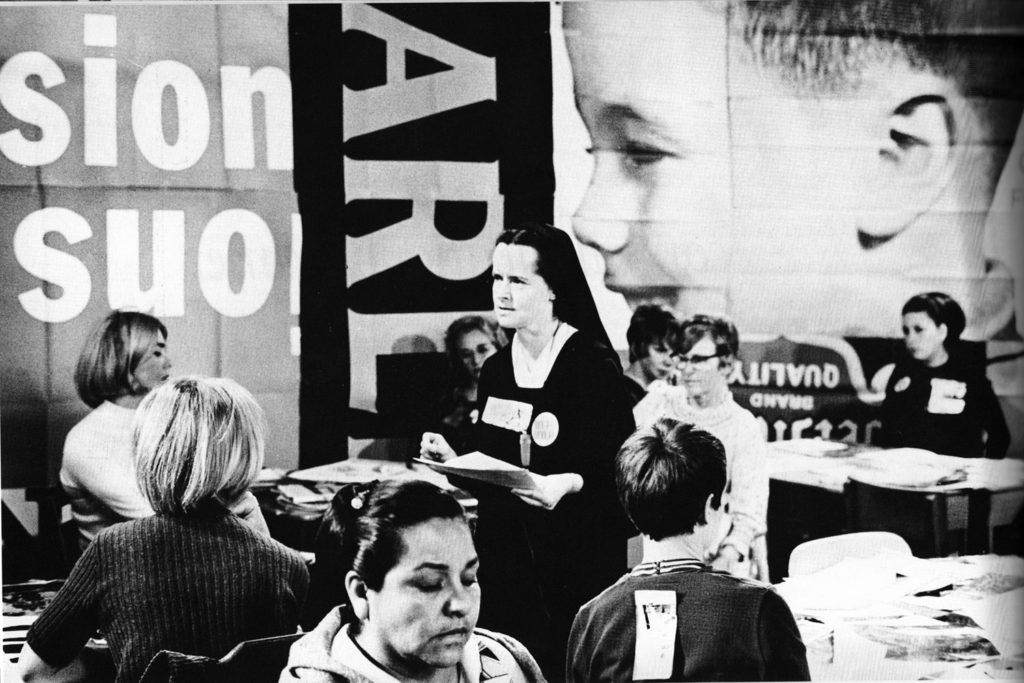

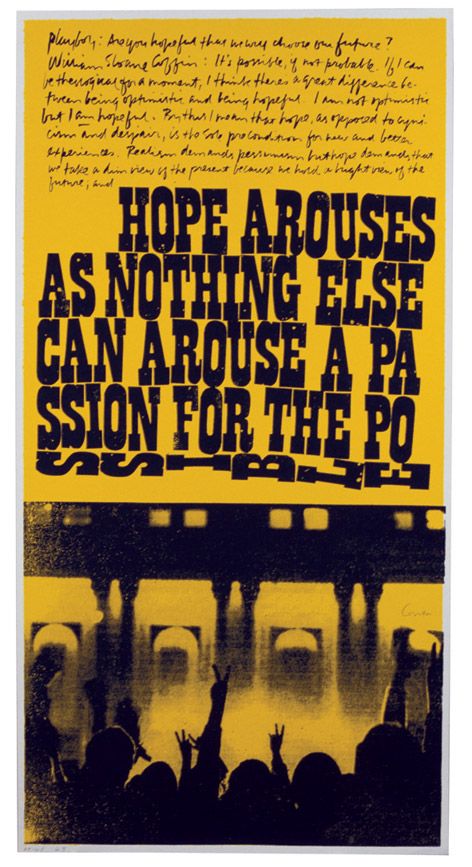

A glance at “Passion for the Possible,” an exhibition of Sister Corita’s work in Mitte gallery Circleculture, might lead you to conclude that she produced work somewhere between Andy Warhol and a greeting card. Curator Rose (who has handpainted his own interpretations of Corita’s serigraphs onto the gallery walls) calls her “the positive West Coast alternative to Warhol.”

There’s a lot packed into that word “positive,” though. In 1964 Andy Warhol showed his Brillo boxes at Stable Gallery in New York. Two years earlier, Corita had exhibited Wonderbread, a composition based on the supermarket bread package featuring red, yellow and blue dots. Some saw them as images of the holy host. Corita added a phrase of Gandhi’s: “There are so many hungry people that God cannot appear to them except in the form of bread.”

And while Warhol was showing his soup cans – without Gandhi quotes – Corita was busy turning the brand name Sunkist into “the word for all things and all men ever since the Son (or the sun which is his picture) became a man and did kiss us in a most human fashion.”

While this might be hammering the ethical message home a little too hard, it may also be what fascinates us so much about Sister Corita today. In a world where New York drug culture has been mainstreamed (rather than claiming stamp-collecting has spiritual value, we talk about “getting our next stamp-collecting fix”), the nun’s moral mission represents an alluring form of otherness. Perhaps she’s closer to Beuys than Warhol.

It’s easy to see most Pop Art, in retrospect, as a nihilistic endorsement of the celebrity-and brand-addicted consumer culture that now occupies most of our field of vision. By keeping words, ideas, slogans, ideals, and causes so central in her work, Corita isn’t so easily neutered. Her work comes out of the unique cultural ferment of the 1960s when nuns, encouraged by JFK’s Camelot and Vatican II, could embrace the swinging counter-culture – and equally importantly, the counter-culture could embrace a political activism infused with some of the more radical and otherworldly values of Catholicism.

Come to think of it, maybe Corita wasn’t so different from Warhol after all; he’d probably have loved to be that upfront about his own deeply-held religious beliefs. And he’d certainly have enjoyed dressing up as a nun.

Credits

- Text: NICK CURRIE