Ghosts War Romance Tattoos: SCOTT CAMPBELL, Great American Folk Artist

|Matthew Evans and Pierre Alexandre de Looz

Shortly after TRAVIS SCOTT announced the first leg of his Astroworld: Wish You Were Here tour, he visited tattoo artist SCOTT CAMPBELL, who inked the rapper and 032c cover star’s skull with a linear, geometric pattern.

Campbell is no stranger to tattooing celebrities – his clients have included Courtney Love, Howard Stern, and Marc Jacobs – and he’s become something of a celebrity doing it, too. In 2011, Jacobs invited Campbell to collaborate on bag designs for Louis Vuitton, and 032c devoted a 40-page dossier to the creative model his work represented. Part visual artist, part artisan, Campbell maintained a practice suspended between old school Americana and a glossy fashion world mainstream – well before it was de rigueur.

As Scott gets tattooed in preparation to tour Astroworld, and Campbell continues to make his mark on pop stars, actors, and branded product lines, we revisit issue 21’s look at a great American folk artist, through an essay, an interview, and a letter from NAN GOLDIN.

The Tattoo and the Word: An essay by Victoria Camblin

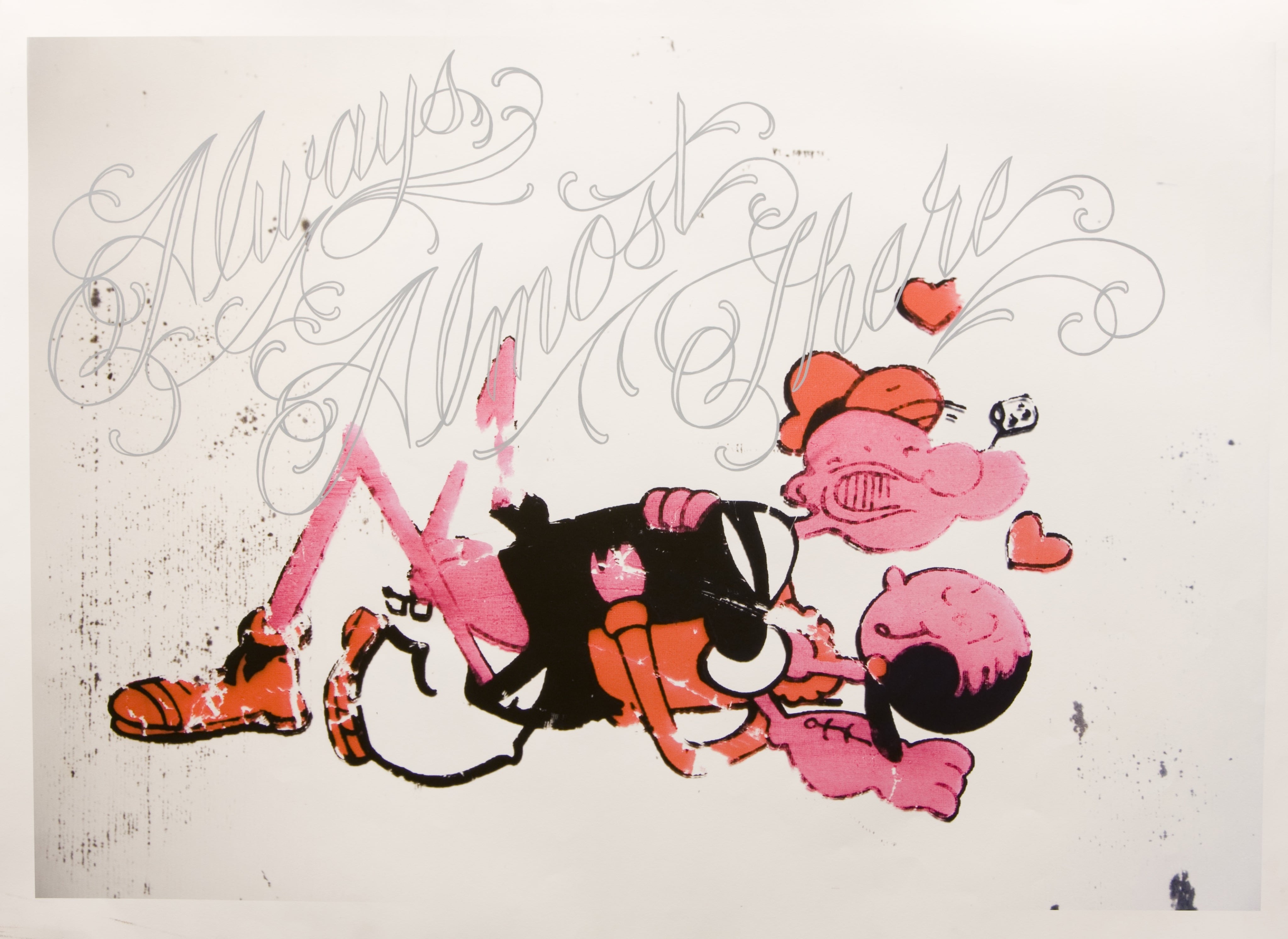

In addition to that “line”-effacing quality, the tattoo has a nebulous relationship to time. It is unique as a medium in that it is an active, simultaneous engagement of the past, the present and the future – at once commemorative and on you and an assertion of agency in the face of a time to come. That latter aspect might be the least obvious of the three, but the notion that a tattoo can determine the future is centuries old. Medical astrologer and occultist to Queen Elizabeth I, Simon Forman tattooed himself with cosmological symbols at calculated astrological moments in the year 1609 – a time when tattoos were considered to both conjure and cure – in an attempt to alter his destiny. Campbell likewise describes getting his first tattoo, which depicts a skull, as a moment of “control,” an aggressive taking-by-the-horns – or putting to death – of what in a parallel dimension could have become just another suburban American destiny. The tattoo’s ghoulish ability to transcend the spatial and the chronological has also infiltrated Scott’s work as a visual artist. In one piece from 2009, a granite tombstone reads, “Wish you were here.” This is what one says to a cenotaph, not the other way around; it is a displaced commemoration, a cry from the underworld, a warning, perhaps a threat.

With what seems to be the exception of the front-most part of his forearms, Campbell is covered in tattoos. Tuttle, of course, has a more or less full body suit, something he found delighted the locals when he traveled to Samoa for a tattoo. “Every Samoan I’d met – man, woman, or child,” he said, “ – was enthralled with tattooing.” He was “treated like royalty” there, given a chief’s name and honored with a kava ceremony, although he admitted he didn’t quite know why. Tuttle’s position – of being seemingly contented to “not know” – reflects the anti-rational impulse that drives people to tattooing, or perhaps to artistic expression in general, regardless of medium. The early twentieth century artist and poet Francis Picabia, when asked why he wrote, replied, “I don’t really know, and I hope I never know.” Whether or not Campbell “knows” why, he is on a first-name basis not only with a star-studded client base, but with the United States treasury, Hell’s Angels, and the executives at LVMH; when he tattoos in Los Angeles, he travels with luggage custom-made for his equipment and uses the Chateau Marmont as an ersatz studio. Campbell has become a celebrity folk artist through a medium that has a history tied to the pre-colonial, the mystical, and the criminal – a medium that can convey a more living autobiography than the pen itself.

In 1981, the writer, ethnographer, and memoirist Michel Leiris, then eighty years old, wrote that he dreamt of having his entire body tattooed with the text he had in mind, musing that his dealings with the blank page were only a poor alternative to those concepts being inked onto his flesh proper. To tattoo or to be tattooed is to write, to be written. The two mediums share a fundamental intimacy and violence; their executor bears and martyrs himself. As Picabia wrote elsewhere, “Every artist has the head of a crucified man,” a notion that perhaps only the tattoo can literalize. It does so, in fact, in the tattoo parlor described by Sylvia Plath in Fifteen Dollar Eagle: “If you’ve got a back to spare, there is Christ on the cross, a thief at either end and angels overhead to right and left holding up a scroll with ‘Mt Calvary’ on it in old English script, close as yellow can get to gold.”

Boys Get Skulls, Girls Get Butterflies: Interview with Scott Campbell by Matthew Evans and Pierre Alexandre de Looz

You recently went to Afghanistan to tattoo American soldiers.

Scott Campbell: I just went, yes, about a month ago; I flew into Bagram Airforce Base. This TV network wanted to do a show where three different directors were asked to profile three different artists. The artists were the Starn twins, Tom Sachs, and myself. I was working with the director Casey Neistat. Casey and I sat down and looked at the template for the other videos, and they were pretty straightforward: an interview with the artist cutting back and forth between images of their work and process. We decided we had to do something completely unexpected. We had to figure out what the polar opposite of what they were expecting was, and then run in that direction as hard as we could. I had been to a few different prisons to tattoo prisoners, and I explained to Casey how I really love the gravity of that kind of situation. Prison tattoos have such a sense of weight and severity to them. They are executed with such a visceral sense of need that is brought about when people are put in such exceptional environments. What’s important enough to them, in that moment, to want to have it tattooed? That’s a big part of relating to someone in that situation. So we thought, what if we were to go tattoo soldiers on the front line and hear their stories? I was skeptical as to how we could logistically make that happen, but we hustled a bit, and eight days after the idea came about, we were getting off a plane in Afghanistan with full body armor and some tattoo gear. I didn’t want it to be political at all, because nothing is more irritating than hearing someone talk about politics who knows nothing about politics – and I don’t know enough about the situation over there to get on camera and start commenting on the state of things. But it is such an intense and intriguing environment. I was going to observe the emotional situation, that’s it.

What was your setup like over there?

So we went over for two weeks and ended up hooking up with these guys, the “PJs” – parajumpers. They’re essentially really bad-ass paramedics. They ride alongside all the Seals teams and Special Forces on their missions. They hold back, and as soon as people start getting shot up, they go in and get them out. They pull out our guys or theirs, any life that might be saved, they’re on it. In a way, they get around the moral dilemma of the war itself: They have the luxury of always being the good guys; they’re there to save lives. I spent two weeks hanging out in their barracks, flying around in helicopters and tattooing them.

What kinds of tattoos did you give them? What were they finding meaningful enough to get tattooed out there, away from their families and girlfriends?

Well, I met them the day after they had gotten caught in one of the worst fire-fights they’d ever seen. They were pretty shook up, and once I realized the intensity of what they went through, I felt like a bit of a schmuck even approaching them. But one of the guys thought it would be good for morale for the crew to blow off some steam and get tattoos. The first guy I sat down with had stitches in his head from where they had pulled a bullet out the night before. He had the bullet in his hand and was like, “Check it out!” So a lot of them got tattoos commemorating that event, symbolizing whatever they had been through the day before. A lot of them were camaraderie tattoos with other guys. Or coordinates of where or when something happened. There was also a lot of family stuff – wives’ names, kids’ names – things that strengthen that connection in absence. It was amazing, and much more emotional for me than I even expected. I didn’t go over there to wave the flag, so to speak. Actually, I don’t know why the fuck we were over there. I got on a plane to go meet people who are running around in the desert getting shot at, and shooting people, without really understanding what the whole war was about in the first place. It felt like a college campus, but with guns. Maybe it was irresponsible of me to go there without doing my homework first, but like I said before, what I was interested in wasn’t the politics behind it all, but what matters to people in those situations. Those guys wake up every morning to the very real possibility of not making it through the day. If you give someone under those circumstances the opportunity to get tattooed right then and there, what’s interesting is what they choose to commemorate.

Did you tattoo any scores?

As in kill counts? Nobody was that dark with it. I was happy to have fallen in with the PJs.

Speaking of rescuing, your parlor’s name is –

“Saved.” a lot of people ask me if I’m born again, or whether it’s a religious reference. But really the name refers to our being saved from “real” jobs, from having to interact with the world in a conventional way. It is about the idea of being saved as in, having built a creative oasis or sanctuary.

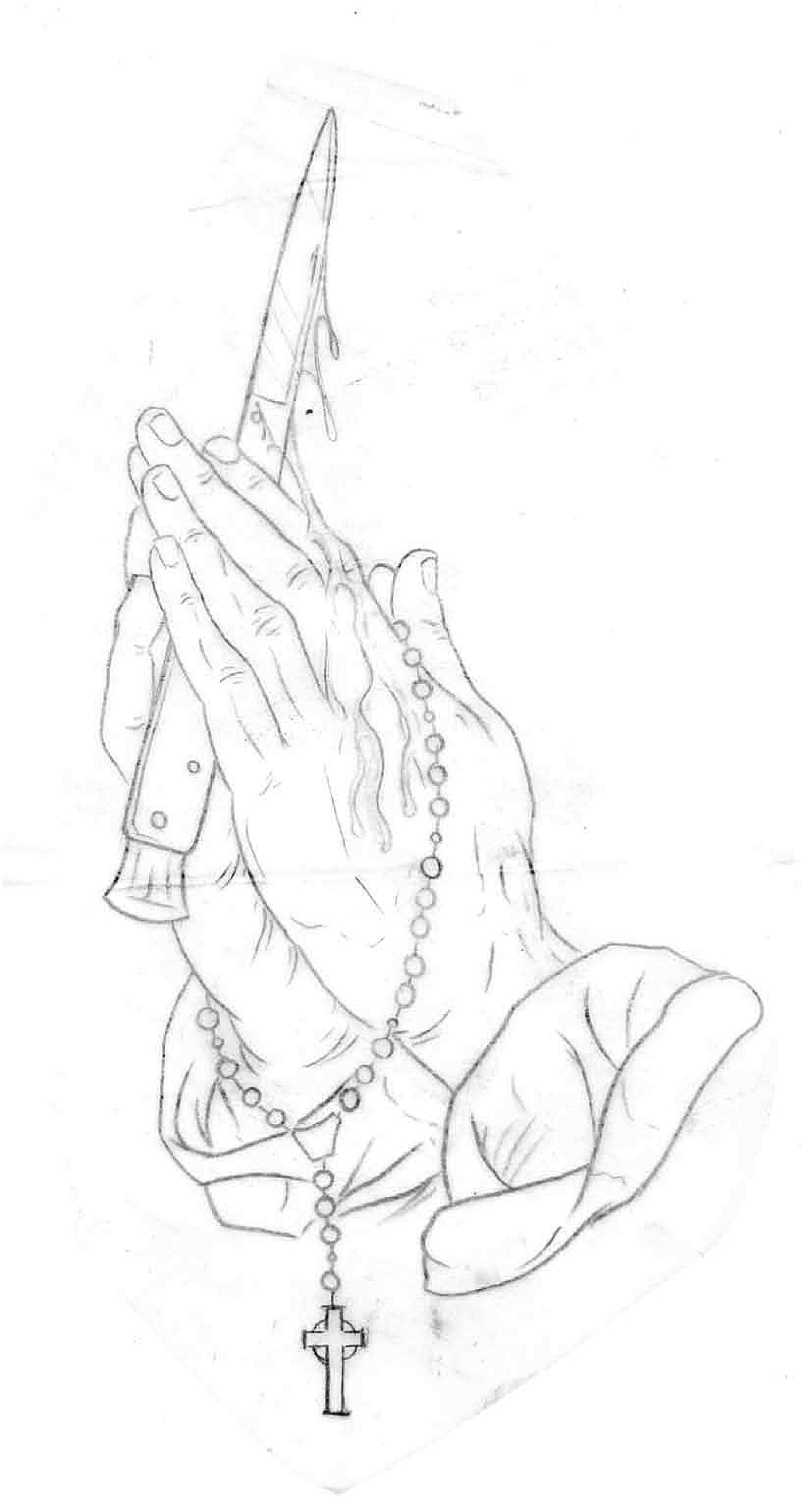

But there is a lot of religious iconography in work you do.

I went to catholic school and half my family is Southern baptist, so my interest in Christian imagery has a lot to do with my own nostalgia – there’s a lot of iconography and mysticism there that still has an impact on me. But tattoo history has always been laden with religious iconography. Regardless of whether or not I still go to church on Sunday mornings, I really love beautiful, powerful depictions of the classic good vs. evil dichotomy.

Your religious iconography feels particularly Latin American, though.

Well I think theirs is the most dramatic interpretation of Catholicism. Take the Mexican crucifix – Jesus is harrowed and emaciated, with blood streaming from his wounds. It’s so much richer visually than what you see in the States. I was thinking about that a lot when I was in Mexico – trying to figure out why the imagery is different down there. I imagined what it was like when the first Spanish missionaries came to Mexico, preaching Catholicism. The converts were supposed to be in awe of the suffering of Christ, to be impacted by how much this guy thousands of years prior had suffered for their salvation. But this was a community of indigenous people that wouldn’t hesitate to volunteer themselves for decapitation if it honors a god. It was a brutal society, in a brutal environment. If you’re going to try to sell a martyr to people of that mindset, you better make him look like he’s been through tougher times than they have.

Do you have strong convictions about America?

I’m an American through and through, and I love most things Americana. I’m certainly proud of where I’m from. I was anxious to get out of there as a kid, but now, living in New York City, I can appreciate the romance of the South. There’s less ambition in the South. Tomorrow and the next day aren’t taken as seriously as they are up here. There’s more an emphasis on now, and they do “right now” as hard as they can. It’s beautiful. that said, I’m not sure I’ll ever live on that bayou again. It’s a really special place and there are definitely times when my soul craves it, but I’m in love with New York in all its mania. my whole life I’ve had a sort of anxiousness, a restlessness. When I was a kid they called it ADD, but I felt it as more of an intense curiosity, and a need to test my effect on the world around me. Call it what you will, but it ended up getting me in trouble or thrown in jail most places I’ve lived. Then I found New York, and New York appreciates that energy. It lifts you up, and rewards you for it. Hell, you can base a career on it.

You have actually been thrown in jail?

Oh man, I wish I had a really romantic outlaw story I could give you. I’ve been to jail a couple times, but never for more than a week, and just for dumb kid mischievousness. If you ignore your dog for too long, he’ll shit on the rug, because getting yelled at is better than being ignored. When you’re a restless kid in suburbia, when you’re lacking real stimulus, you start pushing against the things around you. Getting chased around the town by cops is better than feeling irrelevant.

What would you say are the five strongest American icons?

Stars and stripes, eagles, Budweiser, Yosemite Sam, Bugs Bunny … Damn, there are so many, it’ll take me an hour to narrow it down to just five. Maybe I’m just afraid of commitment.

Strange you say that, because getting a tattoo is something of a commitment.

Eh, I just went all-in. It’s easier when you have a lot of tattoos. If you only have one, then that tattoo on its own carries a lot of responsibility. I just went for everything. Any time I feel inspired, I’ll try to find an empty nook or cranny. I’m on my second or third layer in some places at this point.

People have actually said about you that you have a keen comprehension of love and loss. How is it even possible to have a keen comprehension of such things? Is it an understanding of coping?

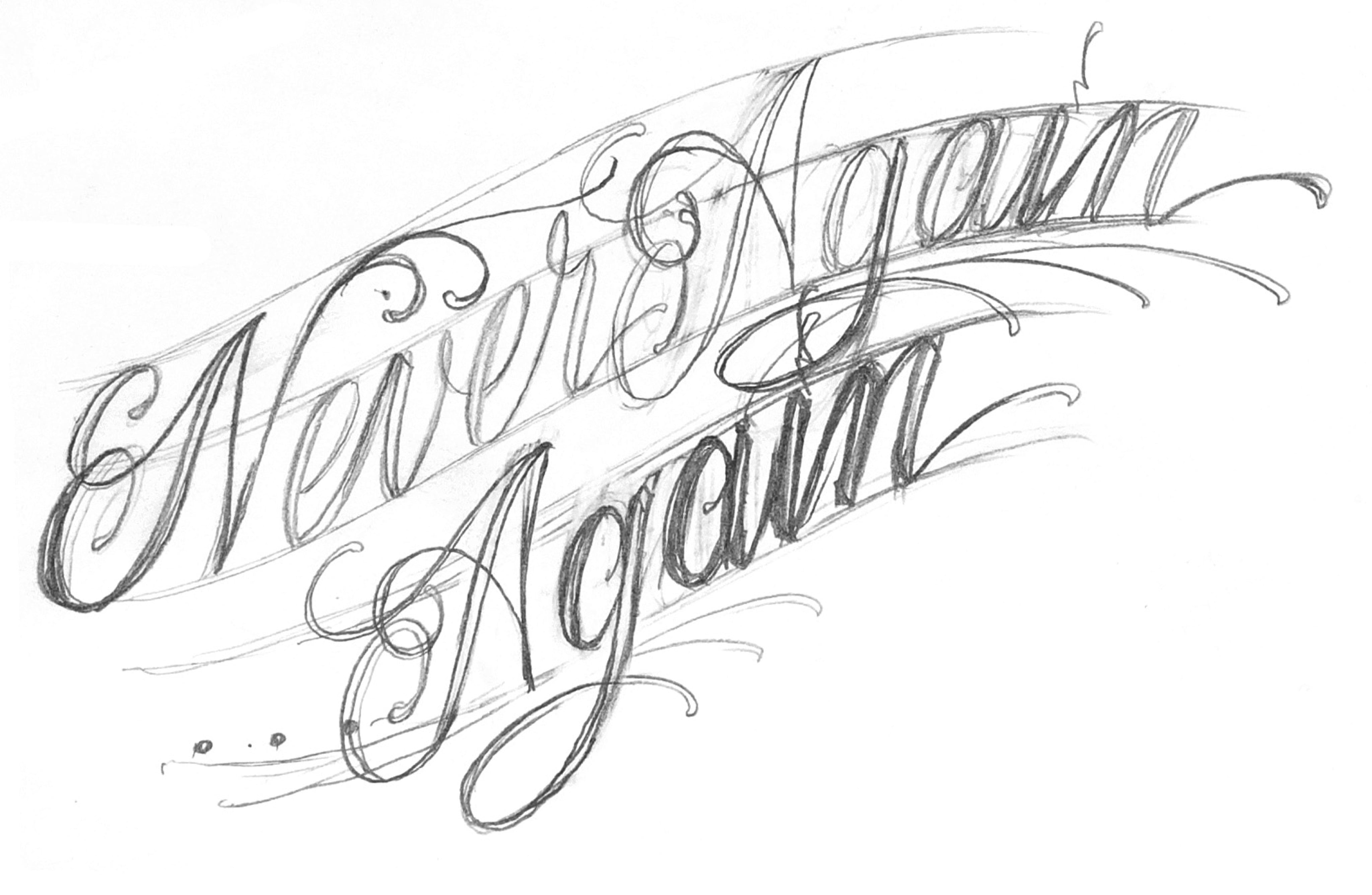

I don’t think “coping” is the right word. I don’t think you cope with inspiration, be it positive or negative. and whatever the driving force, whatever the feeling, when it boils it up to the point where you feel the need to carve it into your skin, that’s when you get a tattoo. Anytime anyone’s feeling something so much that they can’t stand not having it really in them – the t-shirt, the bumper sticker, that’s not going to fucking work. I want to be that idea. That’s also when good tattoos are made. When emotions surpass rationale. There’s no romance in hesitation. Boyfriends or girlfriends names? Fuck yeah, do it! If you love them right now, then love them right now, as hard as you can.

Tattoo artists are such tough guys.

We’re all nerds.

Really?

Every tattoo artist got beat up at least once on the playground. We used to joke around in the shop I worked at in San Francisco that tattoos are like dork armor.

Have you ever tattooed someone you were in love with?

I generally don’t like tattooing people I’m romantically involved with. I’ve been pressured into it a couple times, but it gives me so much anxiety, and each time I swore I would never do it again.

If I came in and wasn’t sure what to get tattooed, would you be able to help?

Sure. Every now and then I’ll get someone that says, “Just do whatever you want” – but you can’t do that. If they come to me with no ideas, I’ll have them write down twenty words, stream of consciousness. and usually once they do that, you realize they have very specific ideas and desires.

Getting a tattoo is a form of being honest with yourself?

Yeah, whether you like it or not. In a way, one’s tattoos take away the luxury of denial. “This is who I am. I fell in love with that girl one time. This one is from when my mother died; this one when my brother died. This one, that time I got drunk with Wes. I did this and I did that. I may look like the bathroom walls of Max Fish, but it’s where I’ve been.” You get a sense of one’s chronology – some are old and faded, some are fresh and new. Some are candid by design, others are accidentally revealing.

What was your first tattoo?

I was fifteen and I talked this waiter into lending me his ID because he looked like me. tThe place was called Dragon Mike’s and Tiger John’s tattoos, in Houston, Texas. I walked in and looked around and said, “I got 20 dollars, what can I get?” He looked me up and down and said, “You can get this butterfly or you can get this skull.” There wasn’t a lot to think about: boys get skulls, girls get butterflies. I got the skull.

Skulls are still a real motif in your work, though; they are a part of that whole Misfits-meets-Mexican Catholic aesthetic.

I mean, skulls are fucking everywhere these days, and I used to use them with restraint for fear that they were too cliché. But I think skulls will always have relevance, for as long as mortality has relevance. I draw skulls in my sleep. I carved them into my desk when I was 12, and I’m still carving them into my desk. The overuse of skulls doesn’t undermine what I make, but in a way maybe strengthens it, because the emphasis is then shifted to the context and the skull is just an exercise in exploring different mediums and environments. Take Jasper Johns’ targets – the symbol doesn’t carry the power of the painting; the symbol becomes a sort of mantra. You hardly notice it after a while. And once you forget that it’s a target, you get lost in the textures and colors and context.

Is it also like a talisman?

It’s like an old friend. Skulls were a symbol with which to push against the standard of cookie-cutter suburban America. I grew up drawing them on backpacks and Trapper Keepers. Anything that could rock the boat fascinated me – any t-shirt I could wear that would piss off my dad was my favorite t-shirt. Getting into tattooing was an extension of that, of being the fuck-up.

So getting that first tattoo was an act of grabbing your destiny by the horns.

I think control is a big part of getting tattooed, and you can feel that both when giving and getting them. When you break up with a boyfriend or a girlfriend, when someone really close to you dies – memorial tattoos are really powerful – getting a tattoo does more than just commemorate that person or experience. You are affected, emotionally, mentally and physically, by forces that are out of your control, and that’s a tough thing to stomach. Getting a tattoo is a very immediate and very literal way to make a decision for yourself that will effect who you are for the rest of your life – and reinforce the notion that you’re in control of it. It helps people process what’s going on in their lives in a physical and tactile way.

Pain is just one aspect of the process, no? In a tattoo parlor there is something going on for all your senses. There is that noise of the gun, the latex gloves, the ink – it’s super-stimulating.

There is a bit of a ritual in getting tattooed, mixing the pigments and laying out the needles and machines, shaving and sterilizing of the area of skin. I suppose it’s all a part of the experience, and serves to communicate the gravity of the decisions being made there. For my side of the exchange, it’s second nature. When you’ve done something so many times, your hands go through the process with their own memory. I’m usually just thinking about the rendering.

How do you feel about the fact that your work immediately belongs to someone else?

It’s a unique dynamic to be in as an artist. I notice as I’m working in more conservative circles that when you say the word “tattoo,” the first thing they think is “permanent.” But actually, in the scope of media I’ve worked with up to now, tattooing is definitely the most ephemeral. The moment you walk out the door, it could get hit by a bus, or get sunburned, or scarred. Skin has a life of its own, which is what makes tattooing so magical. There is no resale value. There is no archival aspiration. It’s for the moment and in the moment. The tattoo addresses whatever emotional situation that person is in at that time. It’s a folk art in that way. It’s not for anything but right now, the action in doing it, and whatever you get out of it. And I think because of that it’s held on to this certain spontaneity or vitality, or whatever you want to call it, that juju – that specialness that has no agenda.

Is there a part of the body that thrills you more than others?

Placement is mostly just a technical issue. The stomach and ribs are really hard to tattoo, because breathing affects it. Other than that, it depends on how much attention you want the tattoo to get. Putting a tattoo somewhere hidden is obviously more for the wearer than an audience. putting a tattoo right on the forearm is assertive and proclamatory …

And ankles and wrists are less confident?

It’s just more discreet. There are things that people want to keep to themselves.

What about particularly sexy parts?

I think tattoos have a sensuality to them regardless of placement – content is sexy. They can communicate a certain comfort in your own skin. They say, “This isn’t that precious. I’m more passionate about ideas than I am about keeping my body pristine. I’m not fragile.”

What do you think of this guy who has the skull tattooed on his face, like a permanent mask? Or the reptile guy? I saw him once, in the Dublin airport. He was alone at the pub’s bar. It was obvious no one wanted to sit next to him.

Most of those guys are just exploiting shock value without really having any passion behind it. It’s like yelling really loud but not having anything to say, pushing buttons and trying to make people flinch just because they can. It’s not really that interesting to me.

What are your thoughts on plastic surgery? Micropigmentation?

It gives me the willies, but, to each his own. Obviously I can’t take a smug, hypocritical stance about keeping your body wholesome, because I’ve written all over mine.

You don’t have any piercings?

No – never been my thing.

So there’s a difference between image and hardware.

Obviously there’s some meaning to a piercing. It addresses the same idea of making a decision that effects who you are, physically. It’s just that for me, tattoos are more exciting because they have a broader vocabulary, whereas piercing just communicates the self-destructive. It bugs me a bit that people usually associate the two things going together.

What about the client who, instead of wanting to control a situation or command a therapeutic experience, wants to be violent to themselves? I mean, it’s all about capturing an impulse, but is there a morality behind that.

There have definitely been tattoos that felt self-destructive that I decided not to do. There was one girl who was twenty years old and came into the street shop I was working at wanting ABANDON ALL HOPE, YE WHO ENTER HERE from Dante’s Inferno tattooed on the bottom of her stomach. I didn’t want that on my conscience. I try to keep it positive.

What do you think of gang tattoos? Or better yet, in the age of “soft” tattoos, what’s a “hard” tattoo?

the MS13 – the Mara Salvatrucha – get some of the toughest tattoos. [Scott shows us a well-known image of a member of the Mara Salvatrucha, with a 13 etched across his face]. Any time anyone is that committed to an idea, it’s intimidating. This guy has committed to it so much that he’s given up his entire identity. No one knows his name. He’s just the man with the fucking 13 on his face. Seeing that immediate assertion of whatever that idea is has an impact.

You are a true romantic, then.

I’m a hopeless romantic. Whether that’s something I’m “guilty” of or whether that’s a virtue, I don’t know.

Are there tattoo artists that aren’t romantics?

The guy who did my first tattoo didn’t give a fuck. You walk down St. Mark’s Place and there are guys giving tattoos in the back of sunglasses stores who don’t give a shit about romance. It’s a good way for scumbags to make a living, so there’s going to be a lot of scumbags making a living off it. And there have been days when the tattoos I was doing that day were less than inspiring, but as a lifestyle, it’s always had this really amazing sense of criminal romanticism. I started when I was twenty or twenty-one, living this completely off-the-grid lifestyle. I did whatever I wanted. I could go to Spain for nine months, Tokyo for six, Paris, Singapore – all literally with a suitcase and a couple tattoo machines in it. I would send my portfolio to a shop, they would set up some appointments, I would make some cash, learn a little bit of the language, then go somewhere else. I spent the first half of my twenties living out of my suitcase, reinventing myself in each new town.

Would you ever hang up the tattoo gun, pursue another kind of life?

I’ll tattoo until my hands or eyes give out on me. as for other career aspirations, I never even had the audacity to believe that things would unfold as they have. I’m just grateful that I can continue to make things that excite me … and continue to put off having to go out and get a “real job.”

Has this job gotten you a lot of ass?

Yes. Also maybe growing out of puberty – who’s to say which came first?

Is there a difference between giving a tattoo to a woman and giving one to a man?

It’s the same.

But isn’t there a sexual feeling underlying the act of tattooing?

It’s certainly much more emotional than physical. The client already trusts you with their physical being, and in yielding in that way, often trusts you with their emotions a bit more than they normally would. Sometimes it’s amazing, and sometimes it sucks. Imagine you had to have an intimate emotional connection with three to five people a day that were randomly selected off the street. Sometimes you come across really great folks that you really learn something from, and then sometimes you come across worthless human beings. There have been times, fortunately not too many, when I poured my heart and soul into a design, and within the first few lines, I realize that the person getting it is an asshole and doesn’t even deserve the time of day.

Do you feel like a whore?

You really do develop an intimate relationship with your clients. Sometimes it’s amazing, but sometimes you get stuck with your hands all over someone and find yourself wishing you were a plumber or electrician – anything but a tattooer. Obviously when it gets to that point, you try to focus on the work and not get emotionally involved. Don’t get me wrong, there have been people who have come in wanting something as cliché as a Tasmanian Devil on their ass, and I’ve ended up having the best time with them. I try not to judge, and pay attention to why they’re getting tattooed. Aesthetics are one thing, but if the tattoo doesn’t address what he or she wants to communicate, it’s just fucking candy coating.

The tattoo itself is a fetishized thing, too, and it has been for centuries in the West – John Smith liked the tattooed Pocahontas, right? Now there is an industry that is made out of that – alt-porn that is all about tattooed girls, “tramp stamps”…

But to say, “Tattoos are sexy,” as a comprehensive statement is boring; then you’re just addressing an aesthetic attraction. A tattoo’s worth depends on the magic behind it. When someone feels ideas with so much force that just saying them or writing them isn’t enough, and they need to physically become those ideas, that is sexy.

Can you speak a bit about your work with Heath Ledger?

When I first met Heath, I didn’t know who he was. He was just this really impatient Australian guy. Fucking annoying, but really sweet. Even once we became friends, he would show up to my house at seven in the morning with tattoo ideas that couldn’t wait. I mean, what can you say about Heath? He was amazing.

The first time, I was in the middle of tattooing someone else, and he came in and was like, “I really wanna get tattooed, I wanna get this bird on my arm.” and I told him, “Cool, lets do it. Next Thursday, 4pm.” Then he said, “Um, I was kind of hoping maybe we could do something now.” So I explained, “Well, I’m in the middle of this, I’m kind of booked up. I’ve got next Thursday available, take it or leave it, pal.” “Alright,” he said, “Give me Thursday. Put me down for Thursday, we’ll do that.” He shows up the following Thursday with this fucked-up bird tattoo on his arm that he had gotten on St. Mark’s because he couldn’t wait. “Can you fix this?” So he came to his original appointment but it was to fix the one he already got. I fixed it up, and he liked it and laughed. We started hanging out after that. He was sober at the time. He had just split up with Michelle and was kind of on the straight and narrow, and I don’t drink that much, so we would hang out at the Beatrice all the time, drink bottles of San Pellegrino and chase girls. It was fun. And then came all the rest of the drama.

How would you qualify what tattooing has now become?

It’s become very public, and very commercial. There are four reality shows about tattoos. But all in all, more exposure brings better understanding, and that can never be a bad thing. I can’t be selfish and just keep it to myself, and I can’t hate on people for being attracted to it, because it’s something I’ve been in love with for years. When I first got tattooed – skull, or butterfly? – you either had tattoos or you didn’t have tattoos. And that has changed, there’s no line in the sand anymore. Everyone has them. The industry has developed a lot because of that, and that I really like. It’s nice not getting searched every time I go through customs. Still, because of that folk art aspect, because of the purely analogue nature of it, it remains special. It can never be mass-produced. Every experience is one-on-one, for each individual.

You’re not working in an overly commercial context, though, or even only in a celebrity or fashion ghetto – you’ve tattooed in Afghanistan, you’ve tattooed prisoners in the Mexican prison Santa Marta.

Prison tattoo culture is especially fascinating – just the specificity of the different systems and the designation of meaning. There’s an incredible depth there. And tattooing in jail is different because in jail you’re in a smaller community. Prison tattoos have a juju and magic just because of the nature of the environment. It’s incredibly small, and it does everything possible to dehumanize its inhabitants. They give them all orange suits. They give them all a number. They do everything they can to inhibit individuality, and tattoos become this last-ditch effort to make sense of that, to differentiate yourself from the guy next to you. It has a weight to it that you don’t see on the outside. It has an importance that’s much more visceral, even desperate – they need it in order to have some sense of humanity in that environment.

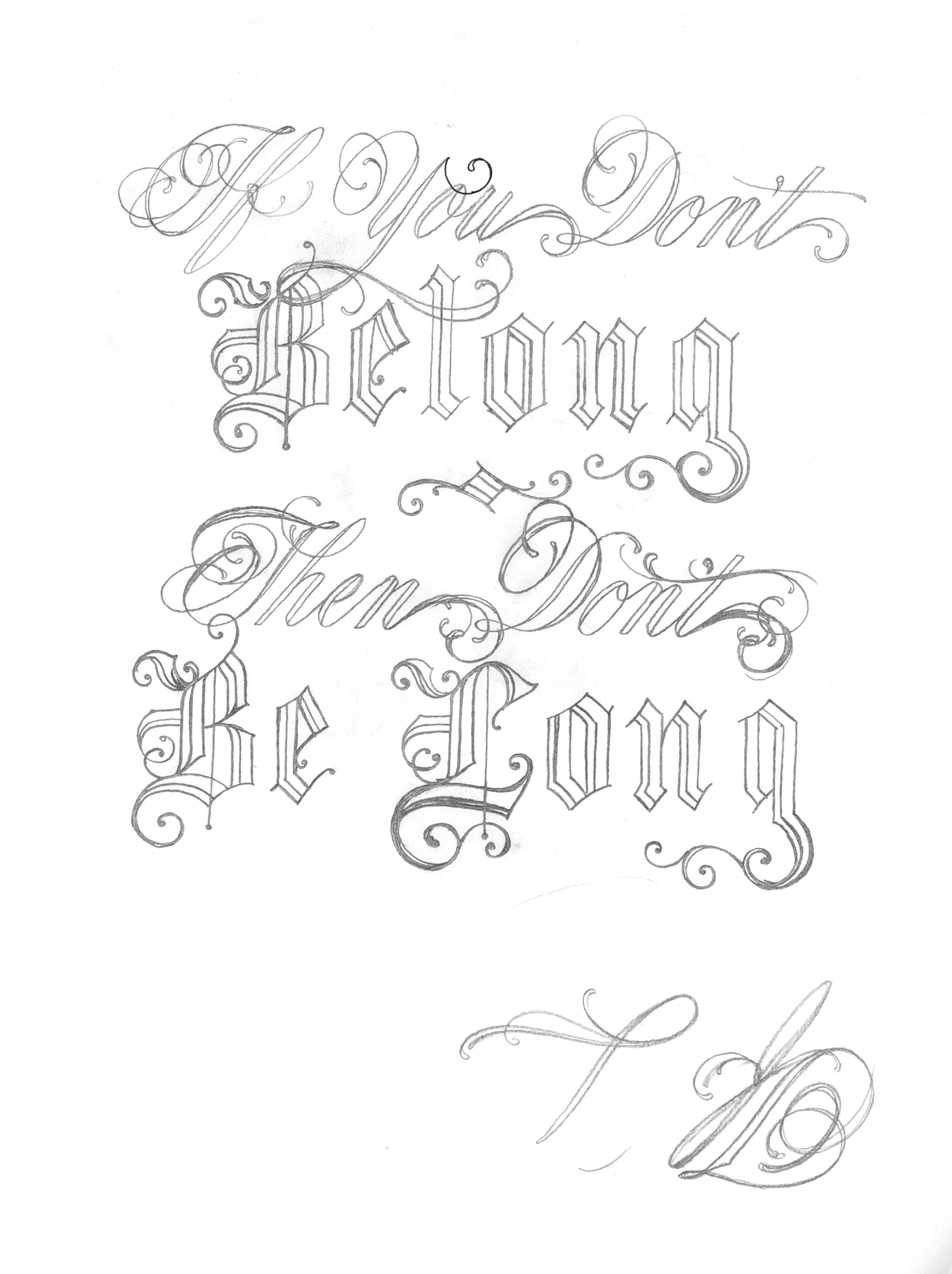

So it’s ownership of self, but also ownership of people like you, a belonging to a community?

Which is the role fashion plays on the outside: you relate to people by how you put yourself forward. But when tattoos are the only form of expression you have – whether for inclusion or exclusion – they are that much more meaningful.

Speaking of Mexico, you notoriously burned your artwork in front of the Vice gallery in Mexico City. It was almost as though you returned to your previous medium – the body – in a performative gesture, in an action. You took the work out of the gallery, literally and figuratively, and did something physical, and that puts you in a lineage with Acconci, with Actionism – you could even do it again in ten years in a museum.

I wish I had thought it through enough to have lit the match with such a composed and deliberate mission statement at hand, but the reality of it is that I didn’t think at all. I burned it down to defend it. It was a knee-jerk reaction, a parental protective instinct that screamed out louder than rationale. I was unhappy with the way the gallery was presenting the work. I tried to address my concerns to the owner, and my concerns were dismissed as the excessive particularities of an unchecked ego. The show had already sold out, and he cited the dollar amount that I stood to make off the sales, as though to tell me to shut up and be grateful. I had to leave for New York the next day, and I couldn’t stand to leave the works alone in a context that went against my reasons for creating them. There was a gas station across the street from the gallery, and I was certain that was a sign that the universe agreed with me. I filled up a can of gasoline, set it outside the door of the gallery, and then went inside and started dragging the pieces out to the sidewalk. I doused the pile, tossed a match, and instantly felt relieved. It’s important to not be controlled by the objects I make, to not hesitate to burn it all down and start over at the slightest hint of insincerity, in order to keep things evolving.

Like the proverbial renewal-by-forest-fire.

The magic is in the idea and the execution. What hangs on the wall is just an artifact of an action.

Never Again . . . Again: A Letter to Scott Campbell from Photographer Nan Goldin

This is a letter to Scott Campbell from his friend, the photographer Nan Goldin. He is her tattoo artist, and her “Saint.” She wrote this letter in April, 2011.

DEAR SCOTT,

You are always so gently giving me the best excuse to get out when all I want is to get in.

Finding you was one of the greatest lucks of my life. At a fashion shooting of Marc Jacobs there was a beautiful Asian girl covered in exquisite drawings. I asked her who did them and she told me, “Scott.” But she said, “It will take you a very, very long time to get to see him. Everyone wants him.” With you and me, I didn’t have to wait. You got the word and we got together quick.

I want you to write my autobiography on my body. You’re the one. I finally found my ghostwriter.

In 1975 I had a lover, the son of of Greek shipping magnate, and he was already tattooed. He had a phenomenal collection of folk art, which was only understood twenty-five years later. He inspired my life-long taste. On his bicep he tattooed my name, “n.g.” – he told me that when we broke up it could stand for “no good.” He introduced me to one of his many former girlfriends. He warned me that she was a genius. First I was too shy to talk to her so I photographed her winding a snake around a man’s torso at a party. Her name was Ruth and she was one of the two first female tattoo artists in America. She had tattooed tribal symbols on her arms and hands. When I met her again in the late 80s she had all her tattoos removed by laser.

In 1976 I moved to P-town. I met Caroline, whose face was entirely tattooed. She was from New Zealand and had been lovers with Vali, a Witch, and they had matching tattoos.

Vali had been a muse of a famous photographer in Paris in the 60s who published a book about his longing for her called Love on the Left Bank. Next I saw her she was living in a cave in Positano. In those days tattooing above the neck was illegal in America.

I got my first tat in 1978. None of you were even born yet. You really missed out.

My tattooist was a close friend, Mark Mahoney. He is one of my best friends even though I never see him. A party part of my life. Once, he even let me give him a blowjob while I was asleep. He was a disciple of a great tattooist, Mark H. I photographed Mark tattooing Mark. A fresh dripping tiger in my kitchen. He inspired me to collect blood rags: the imprint left of a tattoo on a napkin. He’s one of your heroes. He now has a tattoo parlor in L.A. across from the Viper Room on Sunset called Shamrock Studios.

He stayed in Elizabeth Street, where Bruce and Mary and David and Bruce’s monkey and his dog Babe lived. The house lived at full chaos, in a state of future nostalgia, a structural, never quite fatal overdose. Once when B. was brought back from a particularly hot shot he said, “It’s my party and I’ll die if I want to.” It could never be now.

He tattooed a bleeding heart on my ankle. It was my obsessive symbol at the time; I had a vast collection of every bleeding heart. The image surrounded me. It had nothing to do with Jesus, it had nothing to do with oozing empathy – it was about the balance between toughness and tenderness and it symbolized the pain in love.

I took my more than my daily dose of Quaaludes and clenched a beer. I heard that tattooing below the ankle or the wrist were two of the most painful places on the body. I felt no pain. It was his early work. The heart with the flames, the barbed wires and the drops of blood. Years later a plebian tattooist in Brooklyn asked me, “Is that a tattoo or a skin disease?” It hadn’t aged well with me. I had him fill in the red.

In 1979 my close friend and I had dots tattooed on our middle fingers in Paris so we could always find each other. Later when we became enemies we both wanted to cover that memory. I got a matching tattoo on my other middle finger.

In 1995 I had a beautiful friend in Tokyo who lived in and out of drag. He tattooed an arrow on me like his own with bamboo – in red ink, which was considered lucky. He then tattooed a lotus on the back of my neck.

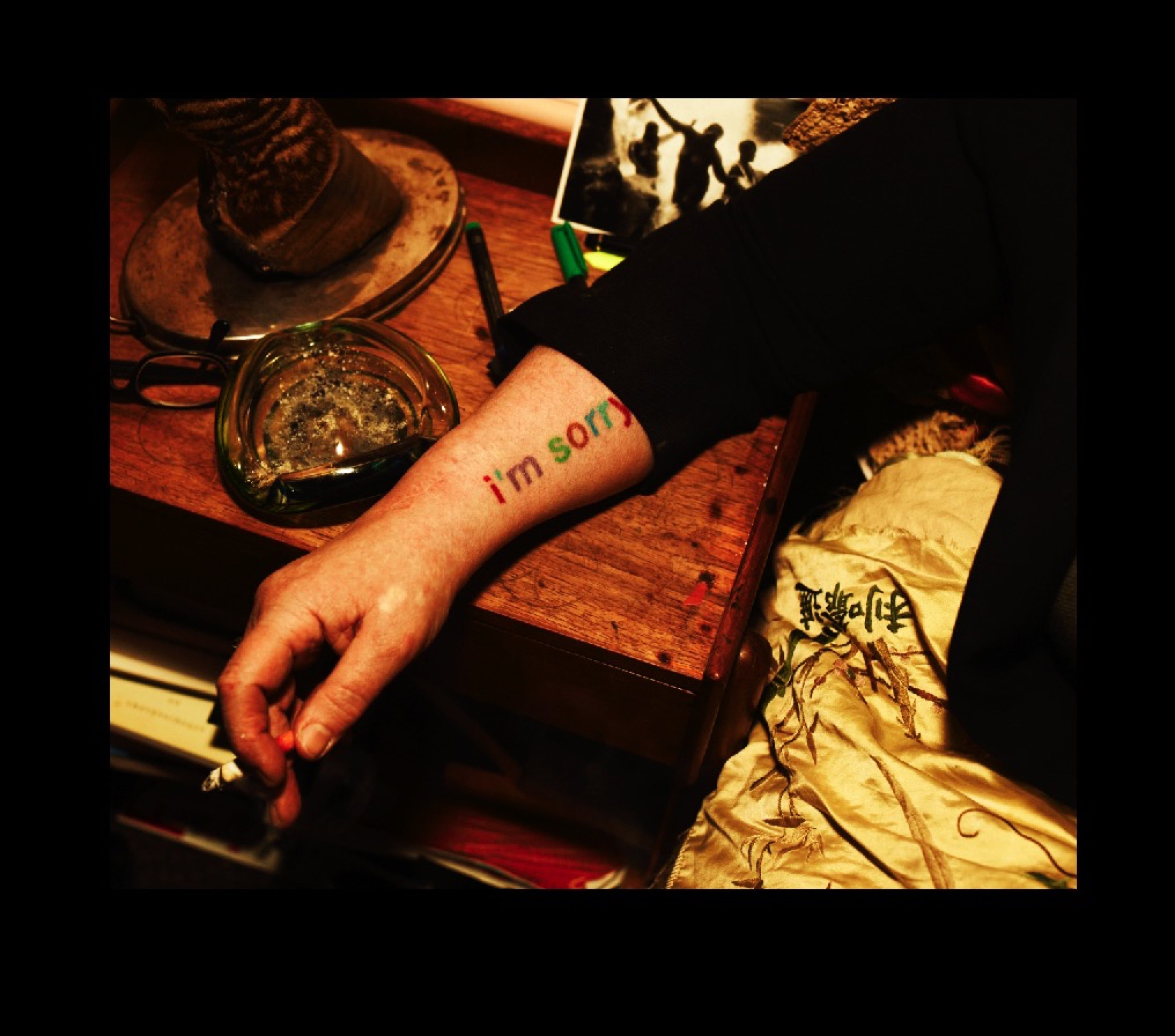

Many years passed. I had lots of ideas. And then I met you. You came over one night to my apartment in Paris and worked on me until 4:00 am. I wanted “i’m sorry” because I was always saying that. It was your genius to make each letter in gorgeous saturated colors. It changes the meaning entirely. Since then I never seem to need to say it. Now I have endless lists of tattoos I am waiting for you to do:

Around my wrist, a script of a music score with a note spelling my sister’s name, a Beethoven piece that she played all the time.

You’re not kidding

Memory Lost

Dad

A path

Eyes like those of an ex-voto

A mouth open screaming in letters made of nails (but you will probably have a better idea)

A train

If my body shows up

The name and symbol of every place I’ve lived – like the

stickers on old steamer trunks – on my entire left inner arm covering burns.

Or maybe you will use the burn marks to design your own symbols.

I’m in your hands.

Lots of hugs, Nan

The Scott Campbell dossier was published in 032c Issue 21. To see the print archive and subscribe click here.

Credits

- Essay: Victoria Camblin

- Interview: Matthew Evans and Pierre Alexandre de Looz

- Letter: Nan Goldin