Not Meant for Re-Use: Pain and Personal Freedom through the Eyes of SANG BLEU

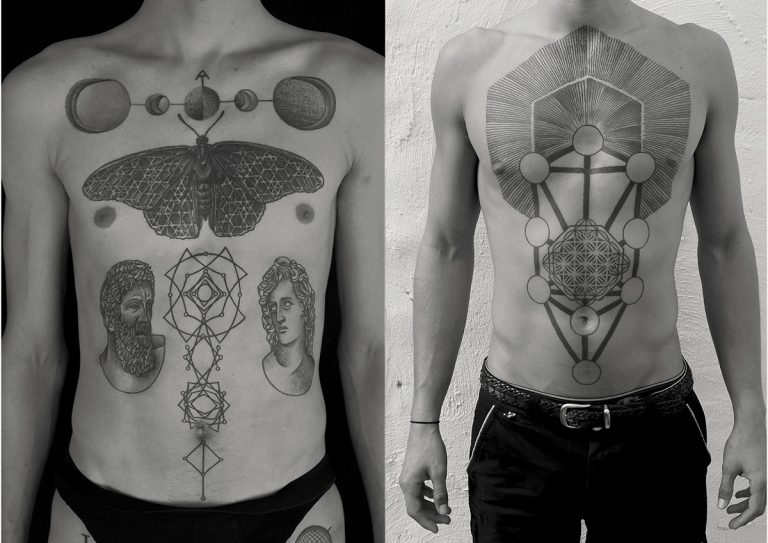

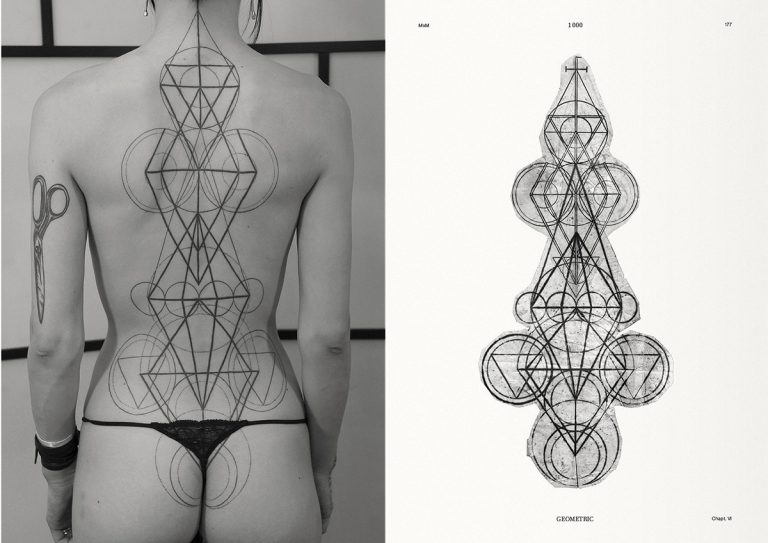

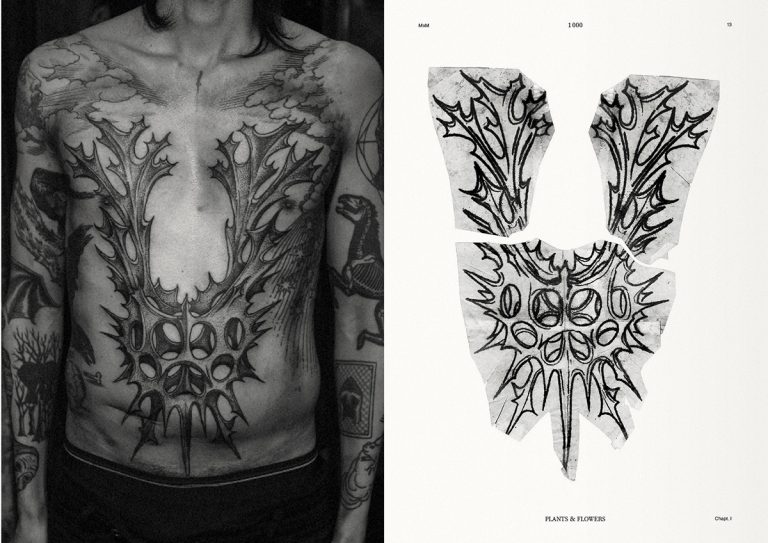

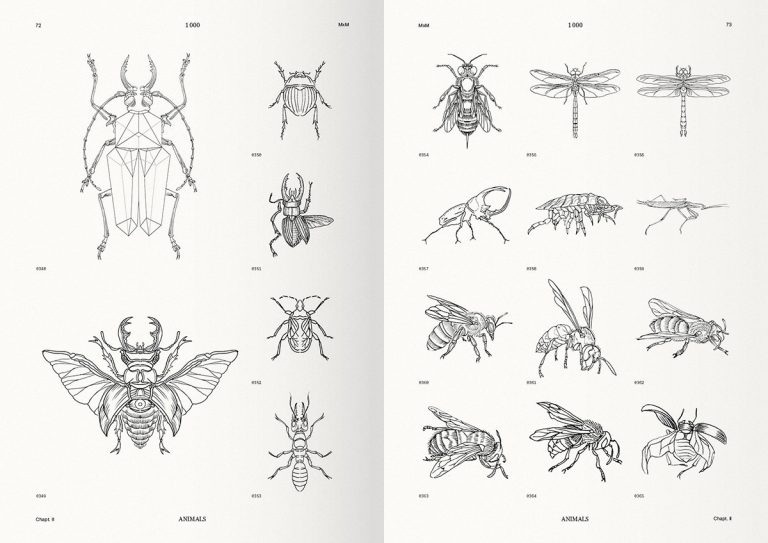

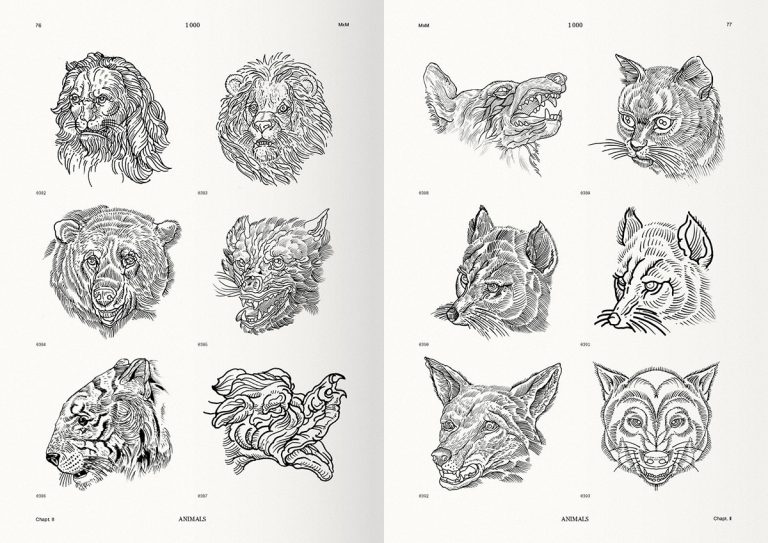

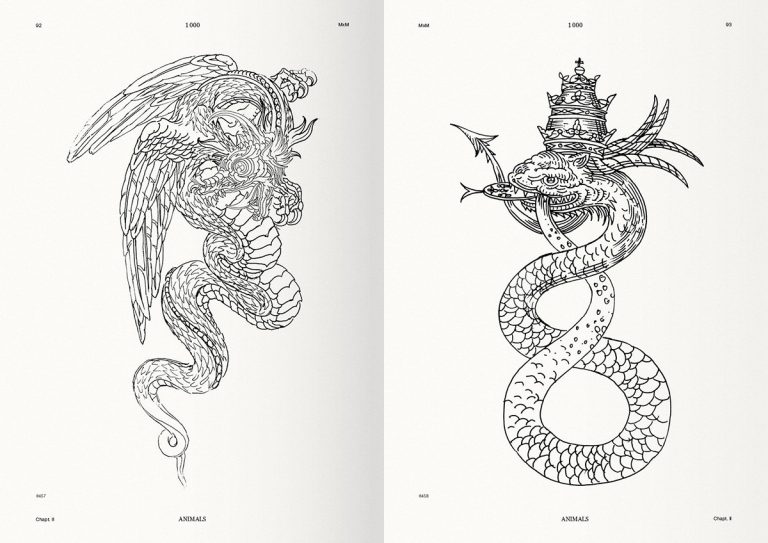

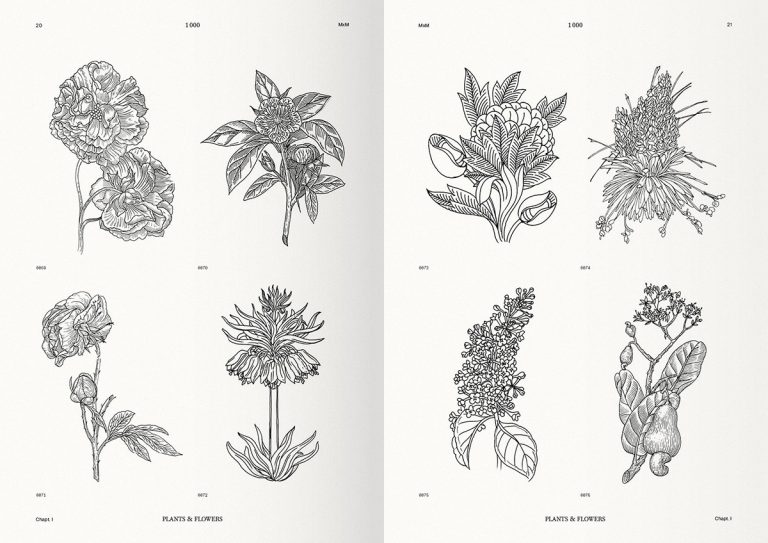

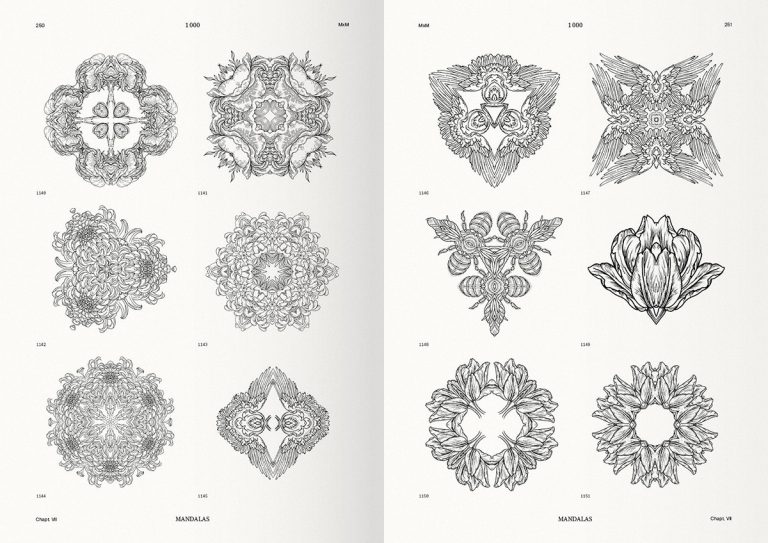

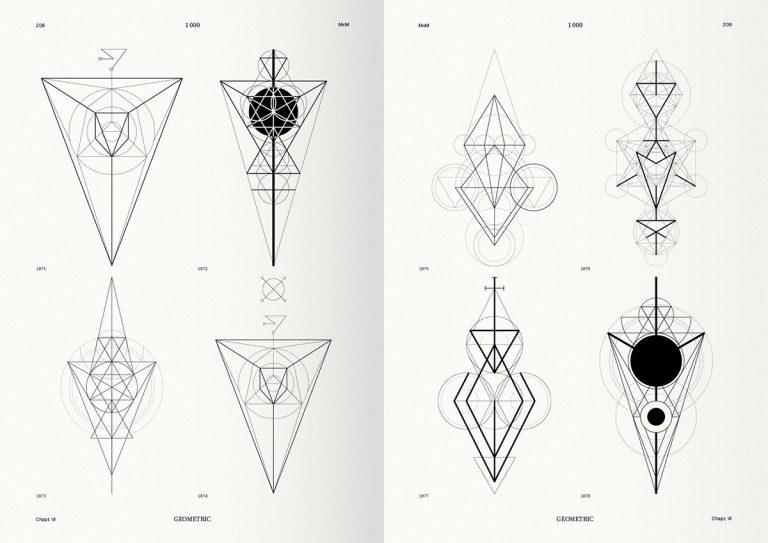

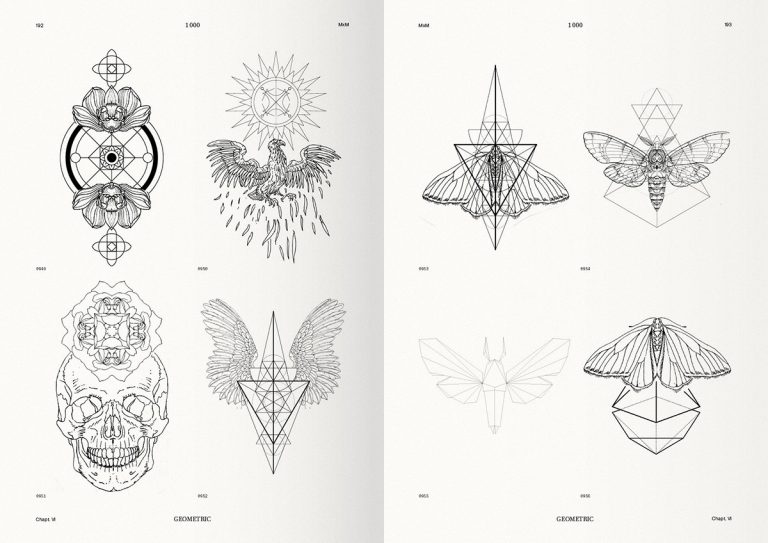

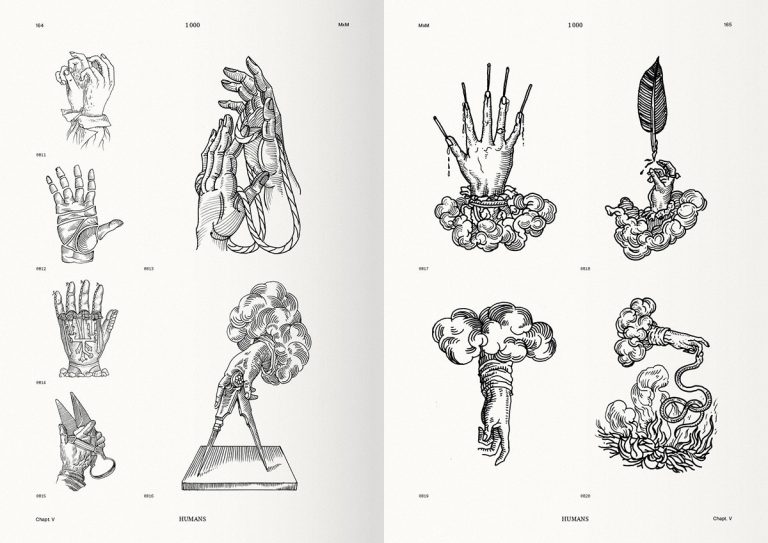

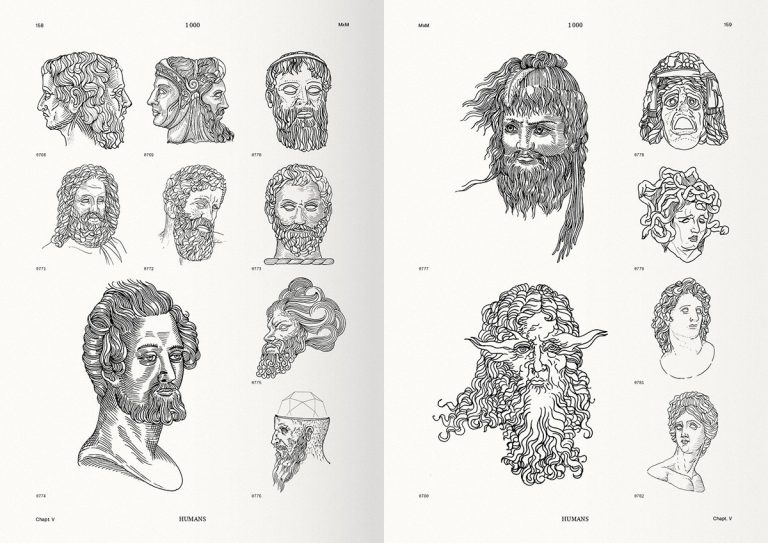

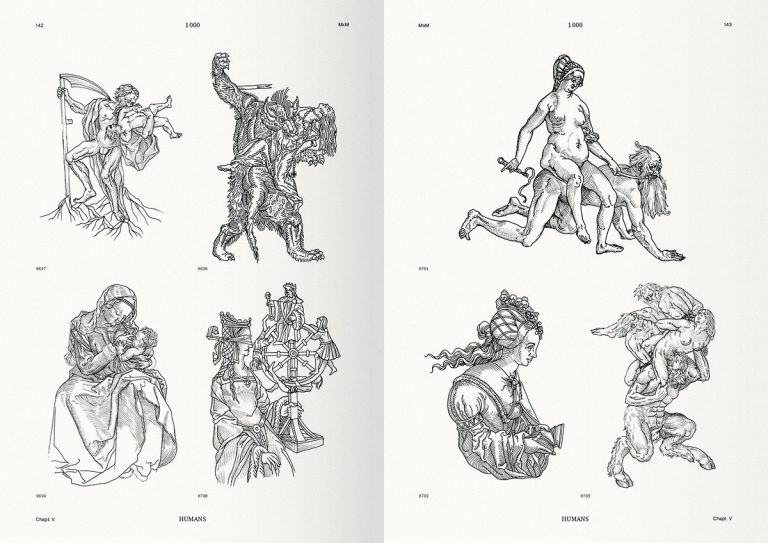

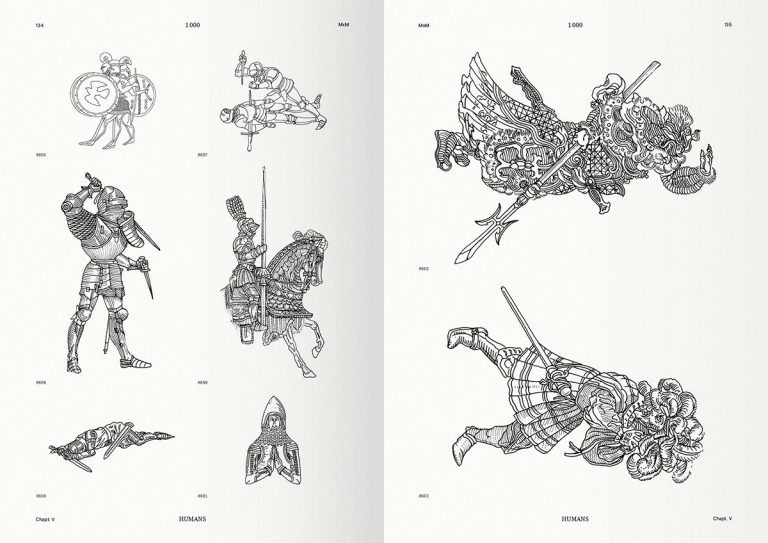

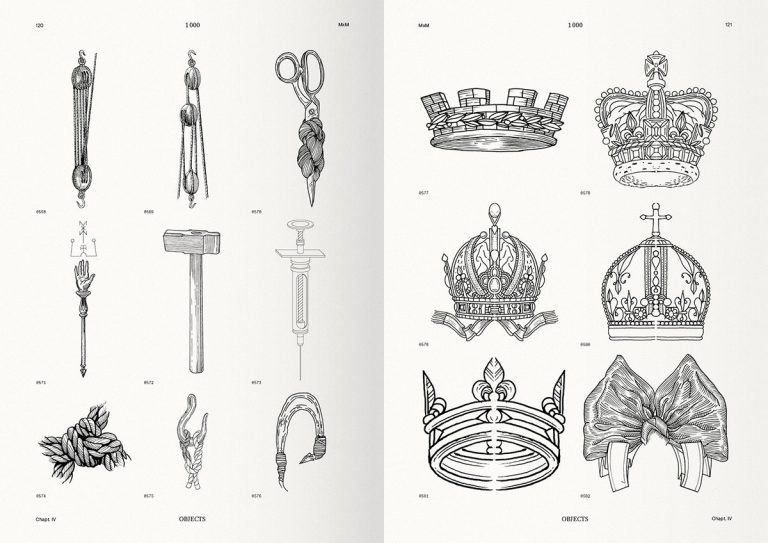

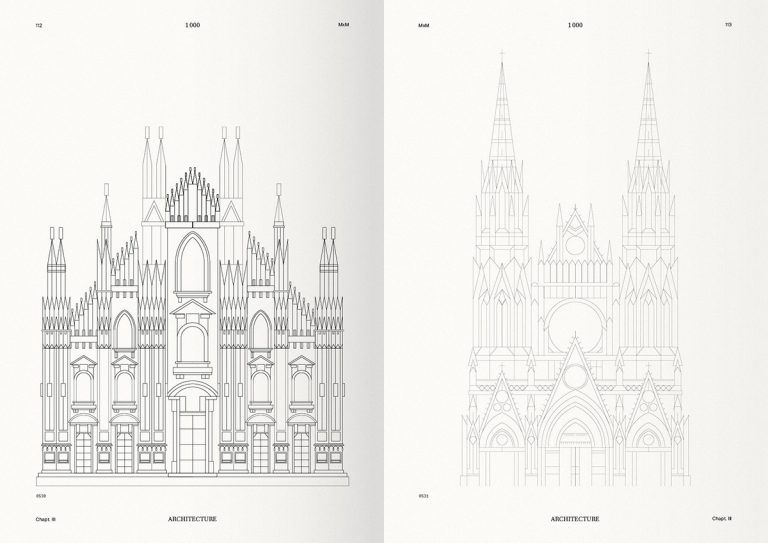

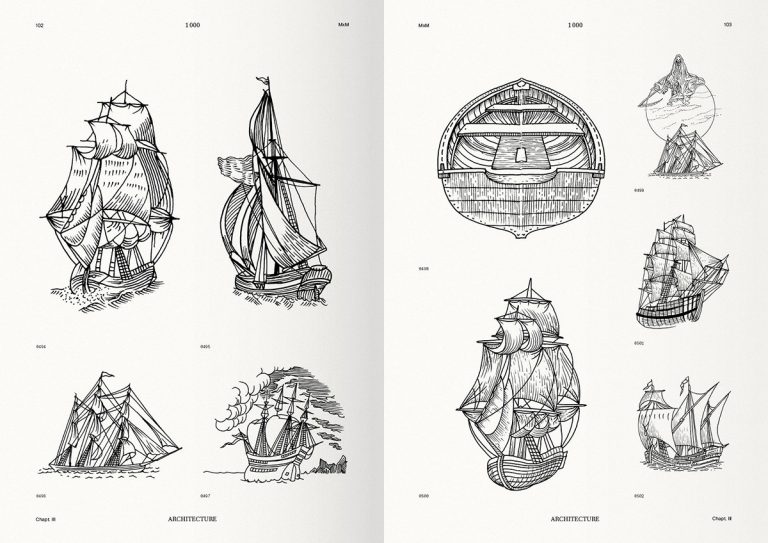

Tattoos simultaneously symbolize real danger and real love. You pay for them in pain, and for the regrettable ones you pay in time. This is a tension that endlessly inspires Sang Bleu founder Maxime Buchi. Alongside his influential magazine founded in 2005, the Swiss born graphic designer has been running a tattoo studio of the same name in London since 2009. Seven years in, more than a thousand of his drafts can now be found in the book 1000. The volume offers versions upon versions of a range of recurring motifs: lions, skeletal hands, keys, roses, birds. It is an approach to tattooing trades in centuries of tradition. His iconic geometric patterns follow ships, wolves, and cathedrals – marking a history of pain and personal freedom.

The earliest tattoos on record date back to ancient Egypt around 2000 BCE, when symmetrical patterns of dots and lines adorned women’s abdomens evoking Bes, a deity protecting women, mothers, and children. These tattoos were made to channel fertility and were reserved for those in high social ranks. Later, in Greece and Rome, tattoos were known as “stigmata” and served to mark criminals as well as belonging – from religious belonging to actual slavery. Over the centuries, tattoos turned to becoming symbols of bad boy-ism – from red-faced British sailors to Japan’s notorious Yakuza. Today, tattoos no longer convey class as transparently. Instead, they mark the “optional” nature of present-day counterculture and express an idea of belonging formed in opposition to normative lifestyles. So what type of outcast are you, an ex-con or just a punk? Could you break my neck, or are you just dressed like you can? Even taken out of the context of criminality, tattoos contain a type of vigor that borders on insanity.

The body is inherently alienating. Growing it takes years, but growing into it is the work of Sisyphus. Clothing functions as an interface to catalyze identification with our physical manifestation. “This is so me,” says a voice inside us when we slip on a snakeskin jacket, cowboy boots, or a cashmere-wool blend suit. But clothing is fleeting. Nobody goes to bed with their shoes on. Once you shed off all these layers, who are you really left with? Tattoos, on the other hand, remain – and can be read like chapters in the other’s autobiography. “The Book of Billy Bob,” for example: An ex-partner’s name inked into your skin for life did not become the cross-cultural punchline it is today for no reason.

In bold strokes and minute detail, Buchi’s tattoos are above all: severe. They evoke iconographic traditions and mystic symbols with a highly intuitive aesthetic that runs through Sang Bleu as a whole. The guiding thread here being inscription: The printed page upon its invention must have seemed as crass as a tattoo. But dedicating space on your body to an idea also lets you annex it. You gain even more ownership over this body, but the idea becomes yours too. In this auto-erotic S&M relationship, you are both master and slave. This intense commitment prevents body modification from suffering the same inescapable fate as fashion: True belief never goes out of style.