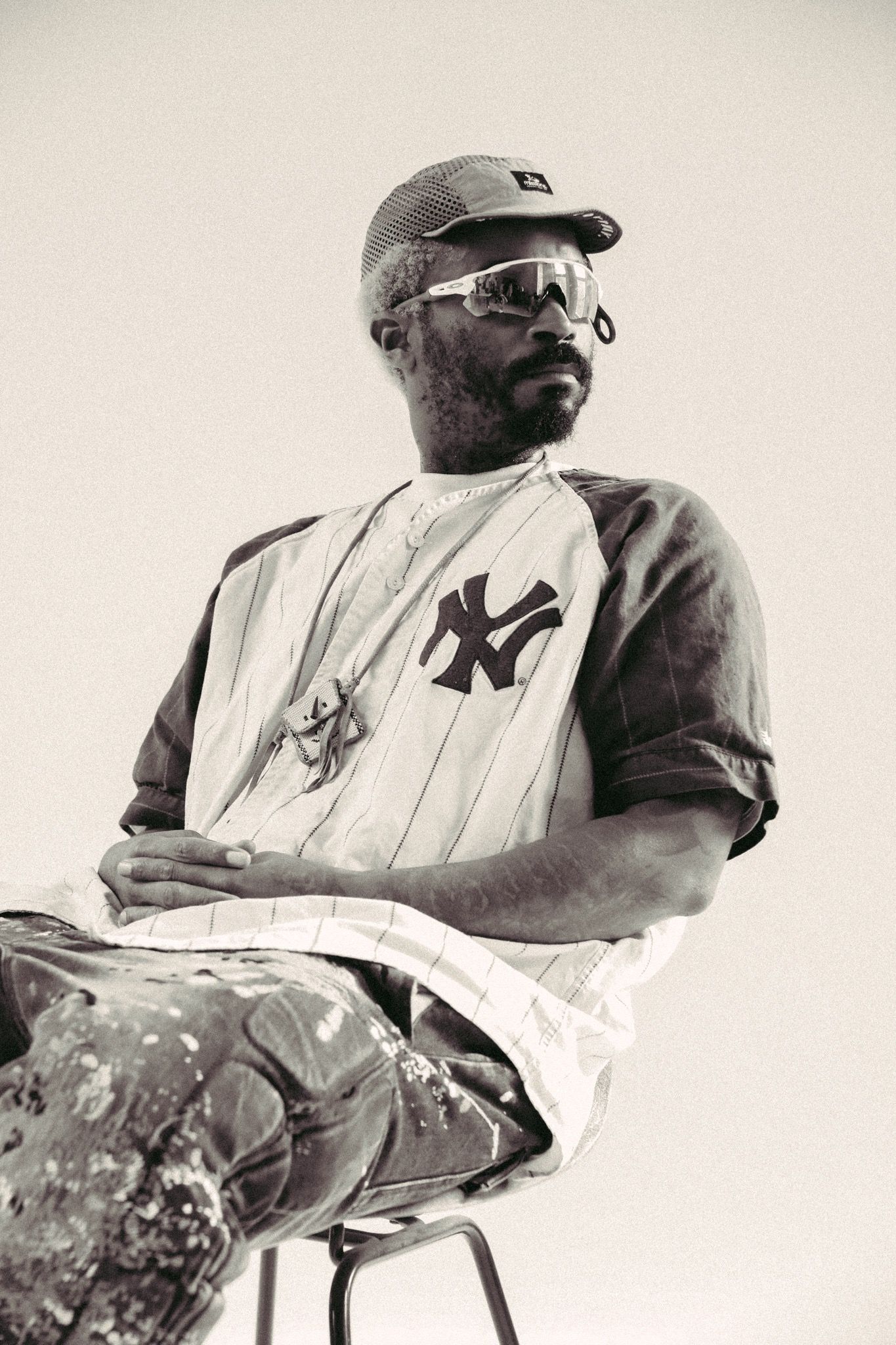

Salehe Bembury on How to Cut Through the Noise

|Franka Klaproth

After leaving Yeezy, Salehe Bembury was two paychecks away from having nothing in the bank at one point. He was applying everywhere, to houses like Versace but also to Zara. He would have even happily taken the job at Zara, but Versace called first. Versace wasn’t streetwear and Italian luxury was unfamiliar to him, but he took the job and ended up running the entire footwear program almost alone. And yet, Bembury’s success never hinged on a single house or logo. From the Versace Chain Reaction to the Crocs Pollex Pod, his designs defined a decade, alongside collaborations with New Balance, Clarks, Puma, Moncler, Takashi Murakami, and numerous others.

Now he tells his story in Salehe: I Make Shoes, published by Rizzoli and designed with PlayLab, Inc. Functioning as both archive and manual, the book reads almost like a diary, tracing Bembury’s fifteen-year journey chronologically. Structured like a high-end scrapbook in the first person, it details how he made things happen: for instance, how he bonded with Kerby Jean-Raymond over a dinner table about being Black men working in fashion, and how they decided to do a shoe together for a fashion show themed around Wall Street and financial struggle. By laying bare his mental and financial states, Bembury’s book is not only about sneaker design but about the headspace of someone who produces them. Added to the never-before-seen sketches, prototypes, behind-the-scenes images, and personal essays are contributions from Bliss Foster, Jian Deleon, Brandon Jenkins, and an intimate conversation with André 3000. In whole, Bembury offers a blueprint for the up-and-coming.

FRANKA KLAPROTH: Congratulations on Salehe: I Make Shoes. Was publishing a book ever part of your vision?

SALEHE BEMBURY: No, not consciously. My father was a photographer, so the act of documenting my work, travels, the people, and cultures I encountered was something I absorbed early. Long before social media made constant archiving common, I was already doing it instinctively. I photographed, I collected, I organized; and over time, I built a digital archive that became a parallel record of my career.

So, when the opportunity for a book surfaced, I realized I had been preparing for it without knowing. In that sense, the book wasn’t born out of a plan, it came from a lifelong practice of documenting and reflecting.

FK: What did revisiting that archive reveal about you?

SB: Passion can sustain you over time. Even when I didn’t fully know the destination, I knew I was on the right road. Sneakers brought me happiness and direction. The process also reminded me how much I value growth. I wasn’t just looking for comfort or easy wins—I wanted to learn, to stay curious, to put myself in different situations and see how I could adapt. What started as a way to earn a living gradually became something more personal, a reflection of who I am and what I stand for as a designer.

FK: You famously landed Versace through a cold DM on LinkedIn. Was that boldness a one-off or part of your method?

SB: At that point in my career, reaching out felt second nature. I was conditioned to put myself out there constantly. Craigslist, LinkedIn, job boards— wherever I could, I was updating my portfolio and sending it around. I just had finished at Yeezy and spent a year freelancing. Some of the work wasn’t glamorous, but it kept the lights on. By the end of that year, though, my savings were nearly gone. I had maybe a couple months left before I’d run out of money, so I started casting the widest net possible. I reached out to Versace, but also to Zara. Funny enough, Zara offered me a job two weeks later - and I would’ve happily taken it. At that stage, it wasn’t about prestige, it was about survival. So, when Versace replied, it wasn’t the result of a master plan. It was persistence, timing, and, honestly, necessity. The boldness came from not having another choice.

FK: Do you need this mentality to be successful in the fashion industry?

SB: I don’t think this method is the only one that works. But now, more than ever, the landscape is oversaturated. With AI and other tools, it’s easier for people to present a polished version of themselves, even to fake it. Which makes it even more critical for creatives to figure out how to get their work seen, and how to tell their story in a way that cuts through the noise. For me, the way to stand out in that period of time was simply to be relentless.

FK: When you joined Versace, sneakers weren’t yet a fashion-house priority. How did you change that?

SB: My goal was to prove sneakers belonged there. At the time, consumers looked to athletic brands, not fashion houses like Versace. But collaborations like Raf Simons with Adidas or Comme de Garçons with Nike were shifting perception. Balenciaga’s Triple S was another sign that fashion could enter the conversation if it was done with intention and research. I pitched Versace on building a sneaker business and promised a peacock product that would capture attention, and that became the Chain Reaction. It launched with massive impact and gave the house something it never had before: credibility in sneakers.

FK: The Chain Reaction became Versace’s top-selling product for multiple seasons—a rare accomplishment for a sneaker in high fashion. After that, you were appointed head of the entire footwear department, which you initially handled alone and later with one assistant. Designing under that kind of pressure, what did you learn about the realities of design at that level?

SB: I’ll admit, formal shoes weren’t my passion, but with an industrial design background and a love of footwear, I knew how to apply myself. And here’s the reality: what should have been a team of ten people was really just me, and later one assistant, Fardin Hazratizadeh. Together, we handled what would normally be the output of a full department. We built everything from the ground up—designing, sourcing, prototyping, and coordinating with factories. There was no buffer, no extra hands. It forced us to be precise and inventive, to find ways to work smarter instead of faster.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that being a designer isn’t just about design. To do it successfully, you have to wear ten different hats—creative, strategic, operational—and execute each at a high level. What separates a novice designer from an experienced one is the ability to understand the bigger picture. It’s not just about sketches; it’s about seeing the entire 360° of the consumer journey—the idea, the storytelling, the marketing, the sales, the final product in someone’s hands. I’ve always said: if a design doesn’t function, it’s art. Design is about execution: solving problems within a system and turning ideas into something that lives in the world. Looking back, I was operating well beyond my bandwidth, taking on more out of necessity than ambition. But we made it work. The sneaker business became one of Versace’s top categories, and that whole shift was built by two people. That’s something I’ll always carry with me.

FK: Many sneaker collaborations barely scratch the surface, adding only colors to old silhouettes. At Crocs, you created seven original silhouettes—rare for a collaborator. What earned you that trust, and why are brands willing to let you go deeper?

SB: What separates me from many collaborators is that I’m a classically trained designer. For me, design has always been more than a name attached to a colorway. I went to school for it, studied footwear my entire life, and worked as a full-time designer before becoming independent. That background meant starting with a blank page, taking a brief, and building shoes from scratch, a skill set not every collaborator has. It’s why I’m often given the freedom to create new silhouettes rather than reinterpret existing ones.

That’s not to dismiss color-up projects; some of the most iconic collaborations in sneaker history were exactly that. But I bring a depth of training that lets me operate differently. A good example is my work with Crocs. That partnership wasn’t just about sales, though it did exceed every expectation and sold in numbers Crocs had never seen from a collaboration. It introduced a recognizable, repeatable design language that built an entire family of products. So, while the culture around collaborations has shifted, what I offer is a balance of creativity, craft, and structure: something that sells, but also builds a foundation for long-term storytelling and product growth.

FK: What was the hardest lesson across your career?

SB: Probably the high of having a job and the low of not having one. Footwear is more than income for me, it’s purpose. When those moments of employment ended, it shook my sense of worth. Over time I’ve learned to separate identity from title or paycheck. I still pour everything into my work, but I don’t measure my value through a company anymore. That perspective keeps me grounded.

FK: You’ve always come across as a true sneaker enthusiast. How has the identity of the sneakerhead shifted over time?

SB: Oh man, it’s shifted drastically. When I was coming up, sneakers were about true self- expression. You gravitated toward the pairs that resonated with you most. What you wore said something about who you were, and it felt like real individualism—at least as much as possible within the sneaker space. Now it feels very different. A lot of sneakerheads today chase whatever’s considered cool, rare, or hyped. It’s almost whitewashed the culture—half the time I don’t think people even know what they’re wearing; they just know they’re supposed to be wearing it. I wouldn’t call it worse, but it lacks the same depth of appreciation that used to exist. Back then, sneaker consumers really knew the history, the models, the collaborators. Now, it feels like the care is gone, and what’s left is more about status than storytelling.

FK: Over the years, countless sneaker designs have risen and vanished. How would you describe the lifecycle of a shoe, and what separates a pair that leaves a mark from one that disappears?

SB: For a shoe to outlast the average lifespan, it has to be born with purpose: design intent, cultural resonance, and storytelling. Any one of those alone isn’t enough. It’s nearly impossible to predict, because at the end of the day, longevity sits in the consumer’s hands. A great example is the Crocs Pollex. That shoe was originally meant to be a limited run of 2,000 pairs—just a moment in time. But fast forward to a few years later, it dominated the sneaker market for three-plus years and cemented itself as an iconic silhouette in footwear history. When my Crocs were released, I also noticed people wearing the back strap flipped over the top of the foot instead of on the heel. At first, the designer in me was frustrated, it wasn’t how I envisioned it. But it became fascinating, and ultimately rewarding, to see the consumer reinterpret it. Those moments proved to me that a shoe’s lifespan isn’t something a brand or designer dictates, it’s something the culture decides.

FK: Your book works as both a retrospective and a handbook. What do you hope younger designers take from it, and how does it connect to the next chapter of your own label?

SB: The book is a 15-year retrospective showing both my design evolution and personal growth. It’s not just images; it’s stories, reflections, and lessons from stepping into offices fresh out of school, negotiating contracts, and balancing creativity with professional demands. I wanted it to be useful, especially for the next generation trying to find their way. In some ways, it’s a design blueprint: showing how a career can be built, sustained, and continually redefined. And all of that naturally connects to my new label. The obstacles taught me resilience, the accomplishments gave me a foundation, and the in-between moments—trial and error, long nights, risks that didn’t always pay off—became the ingredients shaping what I’m offering now. By being honest about the past, the book points to the future and everything I learned is embodied in my own label.

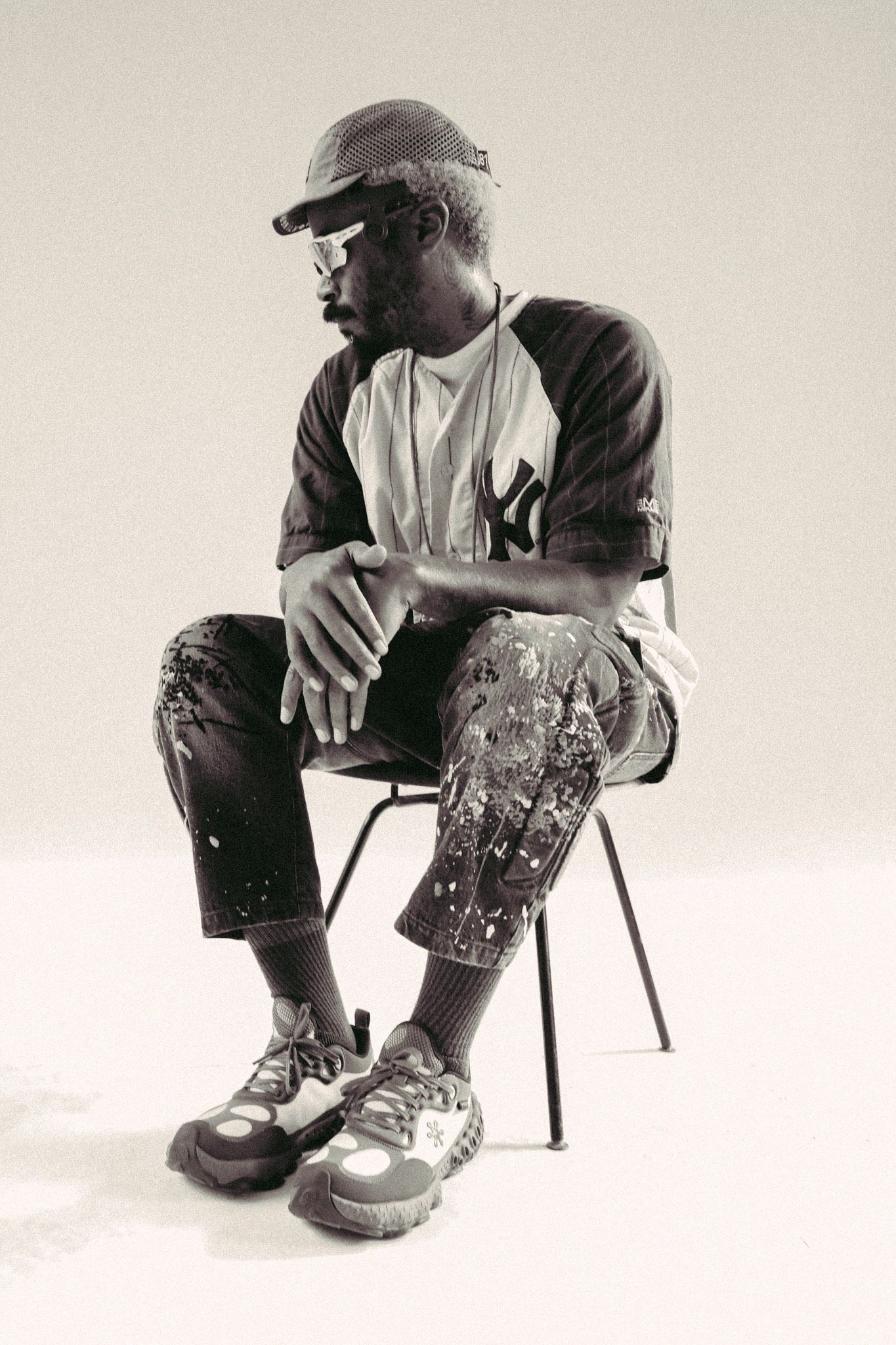

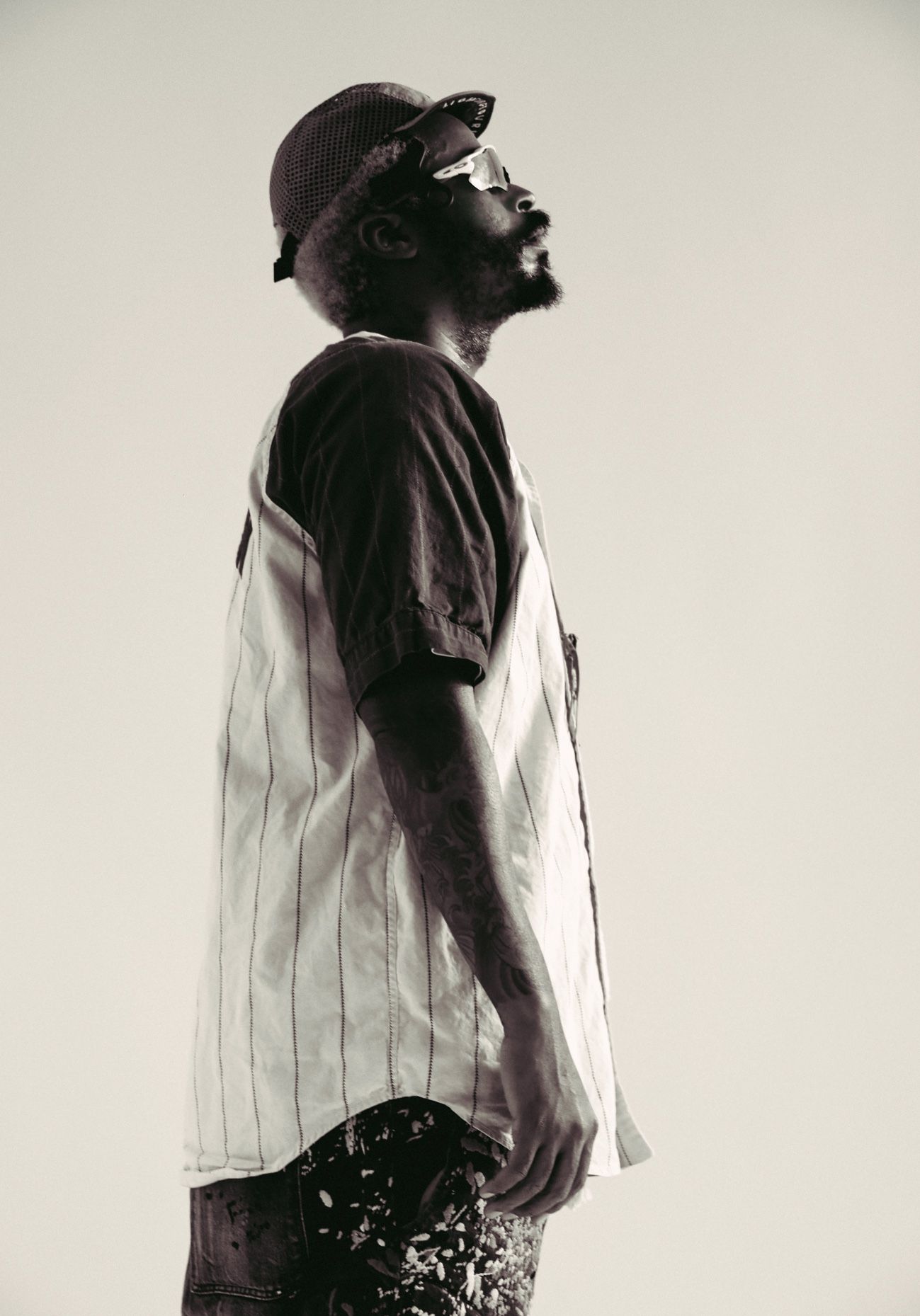

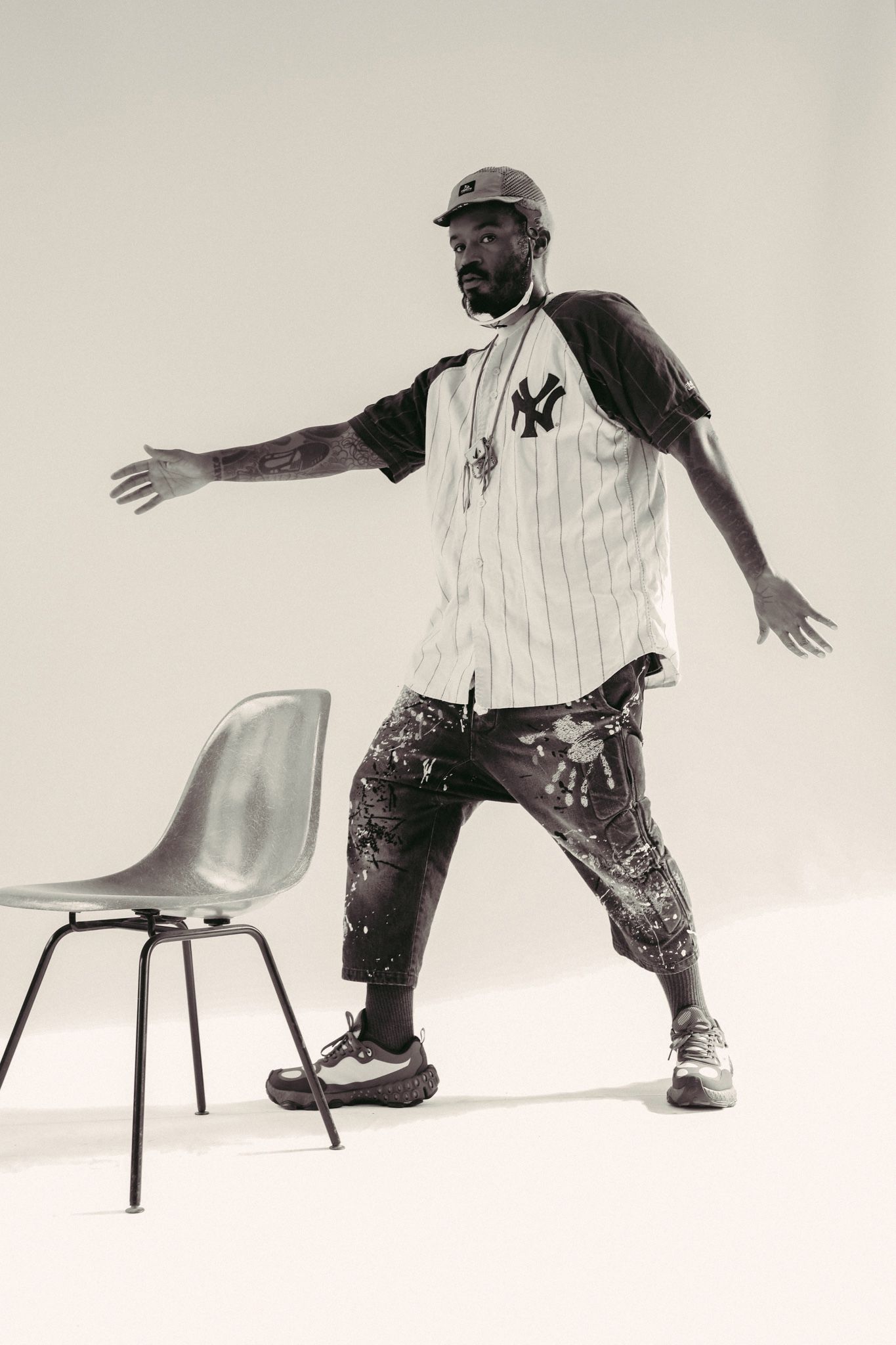

Credits

- Text: Franka Klaproth

- Photography: Byron Spencer

- Talent: Salehe Bembury

- Hair: Rebecca Schmitz

- Production: Mutter Agentur

- Producer: Jeanna Krichel