“Retail Has Become a Game of Seduction”: OMA's ELLEN VAN LOON on the new KaDeWe Experience

|Victoria Camblin

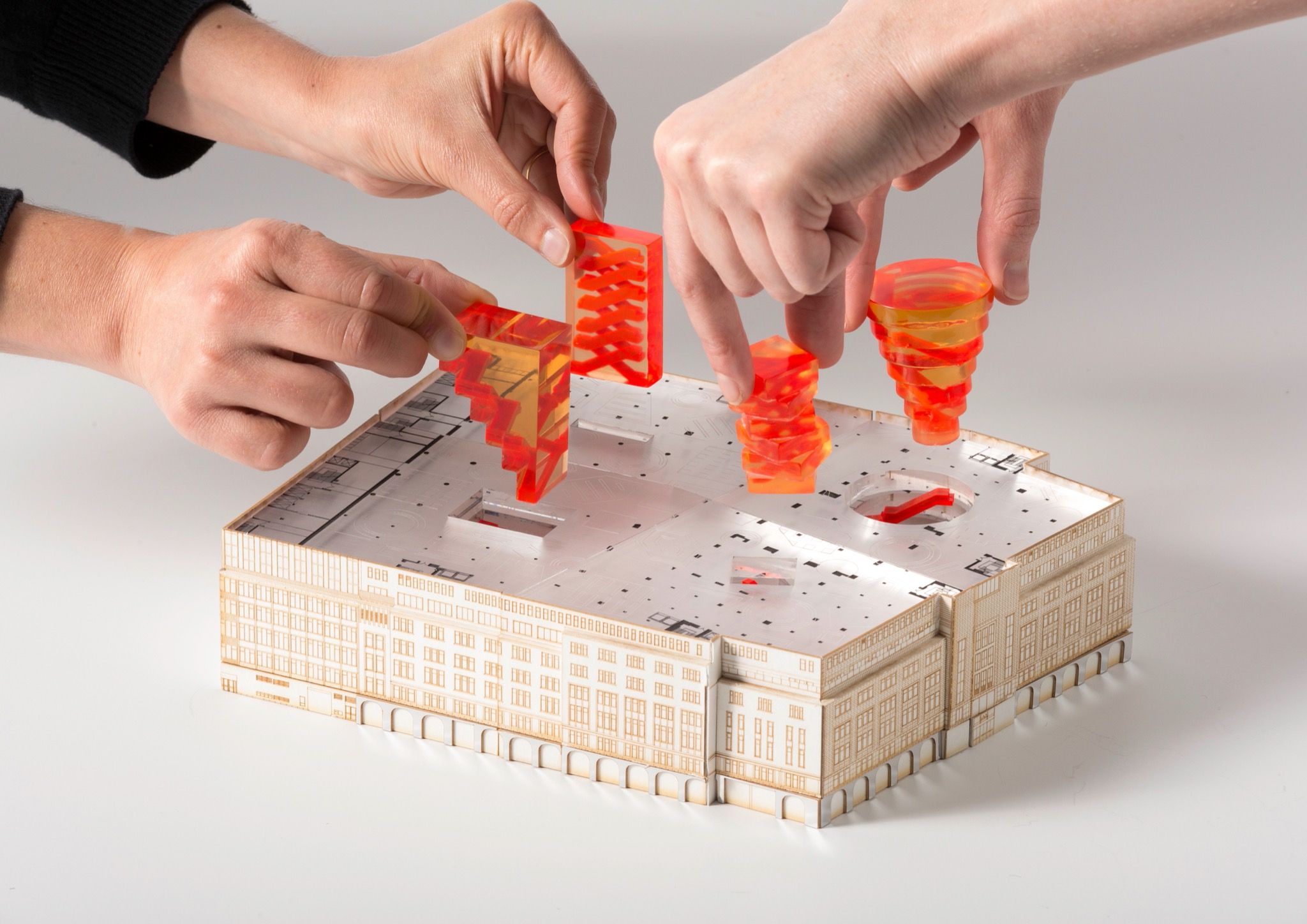

Five years ago, the Office of Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) revealed its plans for the renovation of KaDeWe: the iconic Berlin department store would be renewed in four “quadrants,” each oriented around its own unique core. When the first segment opened in late 2021, it plugged into an evolving dialogue about the future of retail – a domain that, following two years of global lockdowns, must respond to the accelerated ascendency of e-commerce in ever more engaged and inventive ways. For OMA and its partner lead Ellen van Loon, the keys to our storefronts’ survival lie in our relationship to the city itself.

KaDeWe first opened in 1907 and, like many European retail institutions founded near the turn of the 20th century, lost its belle époque grandeur to decades of postwar remodels that prioritized product volume over shopping experience. OMA has long been interested in optimizing the retail sphere. In 2001, the firm co-published The Harvard Guide to Shopping in collaboration with the university’s Graduate School of Design and revealed the New York Prada Epicenter – first of several for the Italian label; in the 2010s, OMA redressed the unfortunate 1970s–90s architectural inheritance of grands magasins including Paris’ Galeries Lafayette, London’s Selfridges, and Milan’s La Rinascente. The KaDeWe masterplan takes on the largest surface area footprint of any OMA department store project so far, and its first “quadrant,” which welcomed the public back in October, has already renewed 14,000 m2 of space – completed, impressively, while the store remained open to shoppers. The design both returns to and upends the more than a century-old department store logic of the atrium: an upward expanse that rises above patrons on the ground floor – typically home to beauty, fragrance, and luxury accessories – inviting consumers, through product showcase and manipulatively placed escalators, to make the circuitous hike up through other departments. The inaugural quadrant’s centerpiece is a walnut hardwood escalator whose material and design makes for an atypical ascent: customers headed to the top are not forced, IKEA-style, to walk the entirety of each intervening floor on their way up. Instead, each escalator that criss-crosses the KaDeWe’s six-story void is shifted just a few degrees relative to the one beneath it, and each floor’s circular opening widens with the climb.

The flow enabled by the escalator – an architectural element that OMA describes in The Harvard Guide to Shopping as an agent of “fluid transitions” that “blurs the distinction between separate levels and individual spaces” – is part of an intentional engagement with the Berlin city plan. Van Loon and colleagues use an urbanist vocabulary to describe the various pathways around the KaDeWe ground floor, an area of multi-brand displays and luxury in-store storefronts intersected by avenues and “streets.” This is infrastructure designed to cater not only to shoppers on a purchasing mission but to commuters looking for shortcuts en route to the Wittenbergplatz U-Bahn station, for example, or to citizens seeking a piazza for meet-ups. Choosing the KaDeWe for one’s encounter provides the option to pick up a coffee on “Luxury Boulevard” amid Rolex watches and Louis Vuitton leather goods, or to escalate the affair with a glass of champagne and some oysters on “Die Sechste”: the sixth-floor food hall, which stays open late. This integrative philosophy, according to Van Loon, is the product of OMA’s study of the history of retail since the industrial revolution, and its applied celebration of the radical and often unnoticed architectural forms in which we dwell as consumers in the metropolis.

Victoria Camblin: OMA/AMO has investigated and experimented with the shopping experience and in-store design and technology for at least 20 years now – in its work on Prada’s epicenters, for example, or with The Harvard Guide to Shopping project in 2000. Has that work informed what you’ve designed for KaDeWe? How much has OMA’s approach to retail evolved in the 21st century so far?

Ellen van Loon: That research was relevant for us because it gave us the design tools we needed to be able to work on such a large and complex building as KaDeWe. From the early studies it became clear that as an architect, the role you can play in designing a space for shopping is rather limited. You can decide on the basic principles, but your design must allow for change.

Would you say that multi-brand retail is particularly uncontrollable as a model, as opposed to the stores you’ve done for Prada or Off-White? How do you surrender to the visual language of all those current and future labels co-existing?

I wouldn’t call it “surrender.” You simply cannot control the design of every single shop in a multi-brand retail environment. You can decide the position of main entrances, main circulation routes, escalators, voids etc., but the rest has to be adaptable. Retail changes every five years and investments like the transformation we proposed for KaDeWe need to work for 20 or more. What makes OMA different from other architecture firms is that we know what we can control, and we can let go of what we cannot control without losing the overall concept.

On the tour, Vittorio Radice described the space basically as a piazza – as a part of the urban plan. You even refer to interior corridors as “streets.”

That’s also why we call it a “masterplan.” The department store is an extension of the city and at the same time a city in itself, so an important part of our work was to reinforce the connection between the department store’s main circulation routes and the surrounding streets.

And a lot happened in cities in those last decades of the 20th century. In the American urban landscape, they took sidewalks away and built freeways, shrank public transportation and de-pedestrianized the city center. By the 1990s you have people powerwalking in malls for exercise.

The idea of the shopping mall had a damaging effect in Europe as well. Department stores, which used to be open, transparent buildings with generous, ornamented interiors, got caught up in the logic of using every square meter to display products and advertisements. We worked with Galeries Lafayette in Paris, which was once an extremely beautiful building but got completely destroyed in the 1970s, 80s, 90s. You cannot imagine how brutal retail was. There were situations where a glass dome was covered with a plasterboard ceiling. Daylight was completely blocked out. Access to the historical balconies around the Coupole was obstructed by shelves with their back facing the atrium.

But this is now finally changing with the rise of e-commerce. There’s no longer the need to jam-pack stores with products; we have fulfillment centers for that. A lot of purchases are now done online; you go to a store for the experience of shopping. Subsequently, stores need to find new ways to attract customers. Retail has become a game of seduction. Last year Galeries Lafayette completed the restoration of its Coupole to its original design, making it once again the main orientation point for the public.

How does making these seductive experiences in multi-brand retail relate to the creation of new public spaces?

For us, every building is a public space. Of course, when you do a bank, it’s technically not a public space because of all its security requirements. But the ideal would be that every building serves as a public space – including parts of secure buildings wherever possible.

There are also cultural specificities to how buildings are used as public space. Mixed-use corporate buildings are said to have destroyed the city center in America, where convention centers and hotels interconnected through walkways made the sidewalk obsolete. But elsewhere, you do see families picnicking in front of a bank building on the weekend, using corporate space as a piazza. I think the way Anglo-Saxons use public space is particularly constrained – perhaps, as you say, you need to sort of seduce them. Was there anything in the Berlin context specifically that changed the way you approached KaDeWe versus, say, Galeries Lafayette or Selfridges?

North America has such a car culture that walking is taboo in many cities. Even in New York, where people do walk, you still have the issue that a fortune is spent on the interior of the most beautiful buildings. But as soon as you step on the sidewalk, you have big holes in the pavement. What makes Anglo-Saxon public spaces more constrained compared to other parts of Europe is that they’ve more heavily adopted this delineation of public and private space. With KaDeWe we focused on making the connection between the interior and the public domain as seamless as possible.

How does the verticality of spaces such as KaDeWe, and the reopening of these historical grand atria that were covered up, come into this idea of making these buildings public and the psychology of access you mention? The word used in our walk-through was the creation of a 'stack.'

In the 1970s, retail buildings were planned with a formula: the ceiling heights and the rent on the ground floor were highest; further up in the building, space was less desirable, so ceilings and rents were lower. The roof was usually used as a non-accessible technical floor for the mechanical ventilation equipment. That was the typical 1970s ‘stack.’ As cities are becoming more dense, public spaces are often sacrificed and in this context the roof can help compensate for this loss. The ‘stack’ we propose puts all the mechanical rooms in the basement and frees up the rooftop to be used as tranquil public space to enjoy the skyline. The roof becomes a public attraction and all retail levels are passed on the way, making them more equal in terms of customer numbers when compared to the ‘old stack.’ In this configuration more customers visit the building, which ultimately means more commercial value.

For a totally different reason we did something similar in the design for the Rothschild Bank in London. The project is situated in a medieval part of the city with small plots and narrow streets – one of the most expensive in the city – so there was a lot of pressure to create as many square meters as possible, but we managed to incorporate public spaces both on the ground floor and the rooftop. The ground floor public space was ‘given back’ to the city, while the rooftop garden was given to the building’s users.

You used the word “calm” a lot during our tour of the new areas, and I am curious about how calmness comes into the retail experience. I would assume that retailers want us not only to spend as much time and cover as much ground as possible, but also to be highly stimulated as we do?

There are two topics that often come up in design discussions: the quantity of products and the background against which they are shown. There’s always the question how much product you can put on display before it starts losing meaning. When you see thousands of products stacked all the way to the ceiling, you stop seeing their individual quality. The same happens when the backdrop doesn’t provide a good contrast. As architects, we have to play with backdrops, like designing a stage for theater. Designing a contrasting background gives shoppers a better opportunity to appreciate the physical quality of the product, which is why they are there in person and not online. Achieving a calm retail space has a lot to do with how you treat these two topics.

I noticed this vocabulary of theater on the tour, too. It’s interesting, because it implies that there are actors and spectators. It’s like how at Disneyland they refer to employees as “cast.” You also spoke a lot about the “program” which is also something we talk about with respect to theater, to museums, to curation – and generally to entertainment. Obviously, strictly speaking, when you talk about the program of a department store, you mean product, food and beverage, and so on. But do you see this curatorial language or thinking coming into retail more now that, as you say, it is about seduction and not numbers?

Curation becomes more important as retail’s focus shifts to its experience. I think the next level, which might sound curious, is trying to make retail space more a home, a space where you want to be and spend some time. This needs a lot of curation – much more than retailers are used to.

And curation also implies working with materials that maybe have disparate origins, right? I’m very impressed that you as designers were able to navigate this territory where there’s so much visual content that you have no control over.

A visually strong material defines the atmosphere of the space in which the product is shown and, contrary to what some retailers might fear, it emphasizes the impact of the product. At KaDeWe we used wood not necessarily because it is surprising to find it in a retail space, but because it stands out and creates the necessary contrast for all the products to also stand out.

Is this idea of realness the reason you went with the wood grain of the walnut on the escalator? When I first saw it, my brain almost wanted to process it as engineered wood, even though it clearly is not – we are just not used to those materials in commercial environments.

Quite often in retail you are confronted with ‘fake’ materials, which creates an atmosphere of apathy, of indifference. Cladding the escalators in wood is not only bold in its scale, but also gives visitors an anchor and perhaps the sense of home that I was talking about.

The idea of comfort, of home – is that new, or is that something that you feel may have been accelerated by Covid-19 and how we relate to our environments?

Covid-19 has made people appreciate more public spaces where they can feel comfortable outside of their homes. For retail this is an opportunity to offer spaces of higher architectural quality. Some clients have understood that and are more open for new ideas, especially the ones that rely on smaller shops, which can adapt more quickly. With larger existing department stores, it might take a bit longer to implement these ideas simply because of their scale.

Has anyone really achieved this balance yet, in your view?

Not quite – but we are pushing to make it [laughs].

Credits

- Text: Victoria Camblin

- Images: Courtesy of OMA