The REAL REVIEW Tells Us What it Means to Live Today

032c contributor and highly productive architecture critic Jack Self has a new quarterly magazine called Real Review, and it has the world’s most enviable tagline: “What It Means To Live Today.”

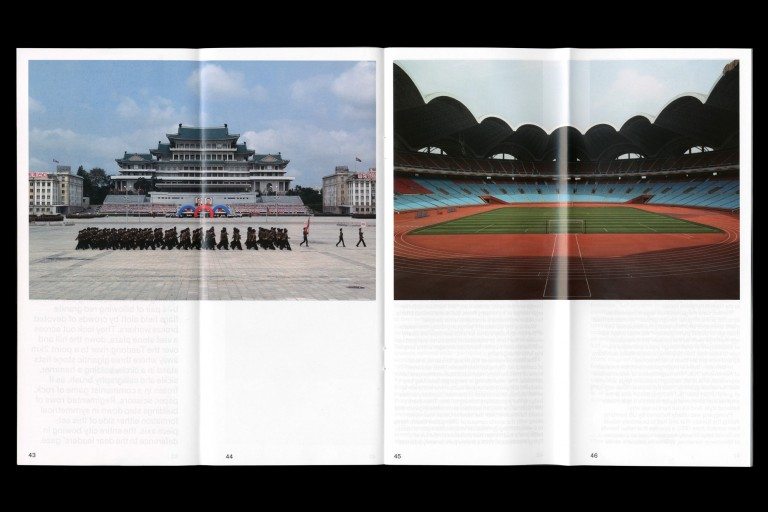

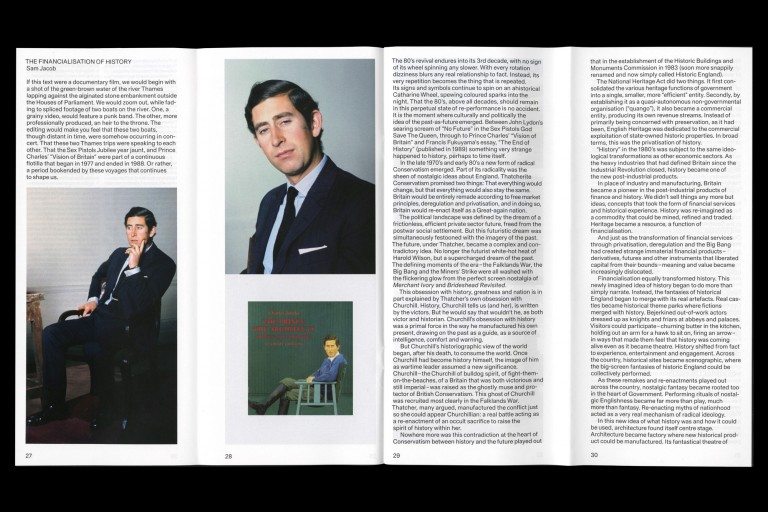

The contributor list includes writers such as Oliver Wainwright, Pier Vittorio Aureli, and Sam Jacobs, and the articles span subjects as such the “Duck House” architecture of North Korea, Prince Charles vs The Sex Pistols on the Thames, and the “cybernetic socialist orgasm” of Allende’s Chile.

Yet it is the format that best indicates the magazine’s objective: rather than the indie-mag cliche of perfect-bound, matte-stock A4 pages, Self and executive editor Shumi Bose went for a long, thin structure, that opens like a thick and demented travel brochure. It is designed to be stuffed into jeans pockets, not sitting idle on coffee-table. It is a designed to be thumbed, read, and passed around like samizdat.

The title is another dead giveaway: REAL proudly presses the medium of “the review” as a perfect form for approaching 21st century architecture: one that can critically evaluate anything from artistic movements to failed utopias. The magazine is therefore at once errant and urgent, writing about the present through the tangled archeology of what currently surround us.

032c spoke to Self about his new magazine, and the uses of living in a post-apocalyptic world.

Tell me about the concept behind starting Real Review, and how you envisioned it as being different from other architecture publications.

Jack Self: Real Review is a quarterly magazine about architecture and is published by the REAL Foundation in London. It aims to make architecture accessible, inclusive and enjoyable. Architecture can be quite insular and dry sometimes, and architectural magazines are rarely very engaging to a general audience. Yet I think there is a growing popular interest in architecture – and the politics of space more generally. The Real Review is about contemporary culture and architecture, helping people who have perhaps no knowledge of architecture find a way into the subject.

Let me add a point about the review as a format, which is perhaps the most unappreciated form of writing today. In the 1960s you used to get reviews of entire disciplines or long periods of time, like “A Review of Early Cubism” or “A Review of the Last Decade in Neuroscience.” Today, the review exists primarily as a big data star-rating process to aggregate product evaluations. Somewhere in the middle is the literary review, which covers books and films, but which can be applied to even banal objects: an architectural review of barbed wire, or the parking meter. Unlike op-eds, the review is always based in reality and the work of someone else, which means we are always building a discourse through the review, never ending a discussion.

I’m curious about the tagline of the magazine “What it means to live today.” Aren’t most buildings dead objects? Is architecture a useful way to think about life?

Jack Self: Architecture isn’t just about making buildings, it’s fundamentally the design of space. This could mean anything that has a spatial consequence. For example, the algorithms powering Uber are architecture, as are the terms and conditions of mortgages – this is because their design has a real impact on how and where we live.

Most people do not see something like the home as a design object. In fact, everything we think of as traditional or normal has been at one time a radical invention. Something as commonplace as the single-person bedroom was invented by an Englishman in 1849 (before that the idea of a room dedicated to one person for sleeping didn’t exist). The corridor, which made privacy possible, was invented in the 18th century. If you look at the Palace of Versailles, which pre-dates this, all the rooms connect to each other directly without a corridor.

These things we take for granted today were all once major innovations. It is important for us to remember this, because the home, the city, the world, are all able to be reinvented at any moment.

The design of sometimes very simple things can have a profound impact on how we live: the father sitting at the head of the table reinforces historical gender power roles. If we make the table round, we destroy that hierarchy. We tend to focus on the endpoint of spatial design: what a building looks like. We should really be asking other types of questions – how was it paid for, who is making a profit, how does its design force us into a relationship with others? Does the use of the building support or weaken our social values?

The Real Review, with a focus on how the design of space affects the contemporary is therefore totally dedicated to understanding what it means to live today.

I had this weird epiphany at the Temple of Hera in Sicily last summer. I was looking at the temple and thought about how it had no roof. About how none of these temples had roofs. Then I realized that all of these neo-classical architects going on their grand tours had to go home and think about what a roof should have looked like in ancient Greece—having to fill in the blank in some transhistorical fantasy. In the information age, are there still any unknown constants left in design? What are the most important ones?

Today we assume that technology and society and the economy all increase as time goes on. We believe in progress. We believe that things are slowly getting better, that every generation is an improvement on the last. This idea, which is so powerful it’s almost invisible, is an invention of the Enlightenment. But in 15th century Italy, most people thought the exact opposite. They looked at their streets of mud and shoddy houses and compared them to the ruins of Roman aqueducts and villas – structures whose technology and engineering precision they could barely understand, let alone reproduce. Renaissance architects believed that the best possible world had been accidentally destroyed. Their vision of their own time was post-apocalyptic. In the same way that we imagine the future as coming from research and development in the present, they believed the future already existed, literally under their feet. Archaeology was a kind of science fiction for the Renaissance mind.

I like that story because it reminds me that everything you think of as common sense or truth is open to debate. Understanding what it means to live today is about analysing the present, but it’s also about reaching deep into the past to make a proposition about the future.