RAF SIMONS RETROSPECTIVE: 1995–2015

|PIERRE ALEXANDRE DE LOOZ

Raf Simon’s SS-23 collection is his final season, leaving behind an epochal influence on fashion history. After 27 years, the designer announced the closing of his eponymous brand, which in its twilight was on autopilot after Simons himself took the role of co-creative director of Prada. Originally featured in our Winter 2014/15 issue, 032c published a retrospective chronicling the development of the most important menswear designer for more than two decades.

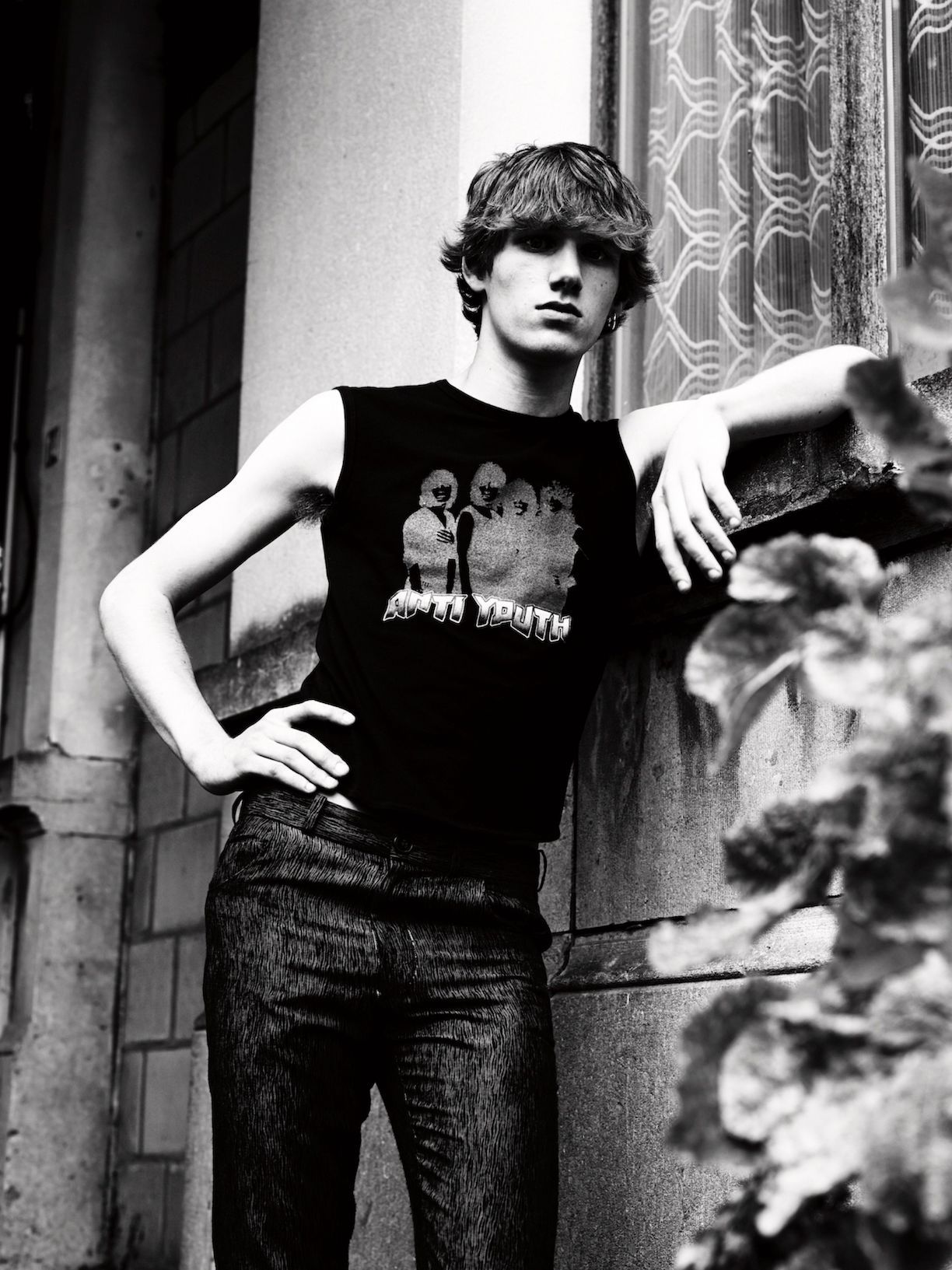

They say that youth is dead – that it has become a marketing demographic, or a disembodied wash of colliding newsfeeds. But, for the Raf Simons atelier, youth is practice. A methodology. An environment. Youth is always becoming. Teeming with questions. Envisioning futures. The Raf Simons label may have aged past its teens, but it still operates in the mental interzone of adolescence.

20 years after its inception in 1995, the label had become an oracle for a pre-internet notion of beauty and freedom rooted in the site specificity of IRL subculture, the iconoclasm of 20th century design, and the melodramatic landscape of suburban isolation. Yet, after 40 collections and counting, the man behind RAF SIMONS remains an enigma.

Published for the first time online, 032c’s dossier on Simons from our instantly sold out 27th issue includes an essay and interview, an archival shoot by Willy Vanderperre, and a poem by Peter De Potter.

I suppose a middle-aged man can claim numerous alibis for browsing womenswear on a weekday afternoon. At the Dior flagship on 57th Street off Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, the sales-floor chatter signaled a rush of speculation. Yet, something else about the boutique kept derailing my concentration, messing with my “critical shopper” zone. I climbed a marble staircase designed to lead the mind to Monsieur Dior’s legendary salons at 30 Avenue de Montaigne, or perhaps to the boutique in Taipei or maybe Amsterdam, wondering how a worldwide, ultra-feminine, luxury experience lands in the care of a radical, somewhat reclusive menswear designer.

And then, suddenly I see him, circling the staircase. Between glossy mullions of fake French windows, an epic high-resolution screen cascades photos of recent Dior collections, collaged with images of geranium pots and close-ups of jewelry, as if the future narrative of a legendary French fashion house was emerging real-time through the matrix of the past.

Raf Simons is Raf Simons. The designer came to prominence with an eponymous label that has ingeniously evolved over two decades, producing a richly varied, radical, and sometimes-severe reformulation of high fashion for men. Simons moved to Dior as creative director in 2012 on the heels of a seven-year tenure designing collections for Jil Sander, a brand associated with doctrinaire minimalism and no-frills luxury. To many womenswear editors, he was a total discovery at Jil Sander in part because menswear has usually garnered much less attention. Raf Simons is an instigator. His arrival at the house of Dior inaugurates an exciting, already critically acclaimed chapter in fashion history, yet I wonder what it all means for the future of couture, of menswear and for the man himself.

“I don’t like to define it,” Simons told me firmly and gently a week earlier, when I asked him what defines today’s Dior woman. As we talked over dinner at his home in Antwerp, the signs were right there. From across the table, I watched Simons, set against a moody spray painting by Sterling Ruby. Simons had patterned a textile in his exquisite debut Dior collection on another painting by the artist with a similarly mottled effect. Below it, on a mahogany credenza, I recognized a Picasso ceramic that had lent its sensual graphic to a midriff knit from Jil Sander Spring/Summer 2012. Maybe, if we talked about femininity, it would reveal some–thing about Raf Simons own brand, which has challenged one-size-fits-all masculinity with every new collection. At the sound of an inaudible buzzer, he moved away from my line of inquiry. We were about to feast on creamy saffron-sauced sole – fresh fish is plentiful here in Antwerp, Simons’ home base. Naturally, I followed him into the kitchen, which could pass for an excerpt of a Los Angeles Case-Study house. Simons wasn’t avoiding me, but merely circumventing my set-up to an obvious answer. To speak with the native Belgian, is to watch his eyes of some clairvoyant shade of blue circle over a mental landscape all his own. He shares his points freely and poignantly, when they come into focus. And they are rarely literal, as if the surface of things were just that, a temporary handle into the viscous space of reality lived and felt.

Not surprisingly, the Raf Simons label has never explicitly defined masculinity. Though its gender seems clear, sexuality floats uncomfortably out of reach. In one particular look from Spring 2007, Simons paired a snug jacket with pleated shorts, which were baggy like a roman tunic. These appeared on a model whose bloodthirsty Motörhead tattoo roared, “Search and Destroy,” across his boney chest. Long sleeveless tops and wind coats, along with slim suits and athletic turtlenecks, completed the collection, which editor Tim Blanks reported as being “Classic Raf.” At the show, Mark Leckey’s 1999 montage Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, provided a hypnotic backdrop. It layers teenage scenes of dancehalls and hangouts, decelerated dance tracks, and synthetic voices, incanting a sinister litany of fashion labels. To understand Raf Simons’ creative vision is to understand that none of these details are presented for their face value alone. The model was a close friend (some say muse), Robbie Snelders, who had grown to manage design production at the label. His tattoo was no less real than the found footage of after-school haunts in Leckey’s video. Simons always threads plenty of meaningful, sometimes hardcore, signs through and around his garments, as he did in this show. Intimidating, perplexing, stimulating, and persuasive, you can be sure Simons sends a message even if it remains suggestive.

I sank into the leather passenger seat of Raf’s Mercedes as we backed into the misty night, on a tree-lined boulevard where young Hasidic men were out strolling – we’re at the diamond trade’s global epicenter, Simons reminds me. However, not all that glitters is diamond in Antwerp. It is also the city of storied nightclubs like l’Ancienne Belgique, where a unique form of 80s EDM called New Beat took hold, merging sounds like British Northern Soul and Detroit techno. “Yeah, it’s a real club,” Raf assures me about our post-dinner destination. “Are you not into it?”

In the way pop music can vividly archive the zeitgeist, it is fashion’s legitimate sister. It is also an integral feature of the Raf Simons brand. Art director Peter Saville, the well-known creator of iconic album covers for the likes of Peter Gabriel, Pulp, Roxy Music, and New Order, called Simons “one of the great pioneers of convergence, transporting the art of sub-cultures into contemporary fashion.” Saville could easily have been referring to Simons’ 2003 Closer collection (Autumn/Winter 2003–04), which used graphic clips from New Order covers. Closer also points to a 1980 Joy Division album designed by Saville. In the earlier Riot, Riot, Riot collection (Autumn/Winter 2001–02), Simons used patches and set lists from the glam punk band Manic Street Preachers, as well as the now infamous and gory picture of the band’s guitarist Richey Edwards having just carved the words “4 Real” on his arm (the band ended up purchasing sweaters). You might say that music made Simons hardcore, or at the very least it is what has allowed him to thrive. Music is how Simons coped with growing up in an exurban township with its share of cornfields and parking lots.

“It was a very, very small situation,” he says of Neerpelt, which counts roughly 17,000 inhabitants today, and at the time “no gallery, no cinema, no boutiques,” and little else for a carnivorous, adolescent mind to hook onto, except music. “The whole existence besides school was built up around music,” Simons recalls. He succumbed to watching his mother’s favorite TV program, the German hit parade Schlager Festival, and then there was Top Pop, which featured stars like Debbie Harry, Blondie, and David Bowie. But the local record store where he found his first New Order album was perhaps most important. As Simons suggests: “That was the time of records and LPs. It all had a huge influence on you. Most of the stuff I was interested in came from England, and later on it was all American Bands, like Sonic Youth.” Equally important were organized outings to nightclubs and open-air festivals like Pukkelpop, which started in 1985, when Simons was 17. One of the headliners Simons saw at the first Pukkelpop was the New Beat band Front 242, which the designer has repeatedly used in his runway shows. He explains, “Belgium has always had an alternative scene and an audience that was interested in an extreme kind of music experience, whether it was electronic or new wave.”

We zip ahead as if the car engine has tuned into the same dance station we are listening to, which plays an ever-accelerating rat-tat-tat. Raf loves driving. When he travels abroad, he often rents a car just to cruise around, which may be one reason he has an open affinity for Los Angeles. But, just as the music peaks, we stop abruptly. A field of barricades reaching beyond the glare of the headlights blocks our way to a party, where much of Raf’s inner circle has already convened.

Simons doesn’t seem like someone to shirk from an obstacle. With an industrial design degree from a university in Genk, Belgium, he found himself cold broke at 23 and facing a familiar sense of entrapment, “I love them and I am thankful for all their support, but it was the ultimate horror to live again in my parent’s house. ‘Jesus,’ I thought, ‘I have to find a way out!’” Simons exclaimed. His emphasis reveals a palpable need for the open spaces of self-realization.

In his family’s backyard, Raf Simons started to design and build furniture, which had been his vocation while in school. “I went through the whole thing: wood, metal, leather, and ended up doing some kind of presentation in a little gallery that only a handful of people in Belgium could see. Good luck in Belgium! It was not a living. My drive at that point was to live in the city, to experience again an environment that I could relate to,” he recounted. Simons supplemented his income by flipping decorative objects that he unearthed from flea markets, especially midcentury modernist glass, ceramics, and furniture. “I was in love with that since I was young. I don’t know why. In my design education, it was problematic. I was obsessed with pieces by George Nakashima, Jean Marais, Charlotte Perriand, and Jean Prouvé, which are now so popular. My generation grew up in the 80s and had to adore Philippe Starck and Memphis. I hated it.” Meanwhile, Jaak Simons was equally displeased about the fact that his son didn’t have a job, which prompted an auspicious decision. The young Simons visited an unemployment office and took the first job – with a landscape architect – that was offered, unwittingly setting the future creative director on his path to Antwerp. At the steering wheel, Simons is thinking in split seconds. He shifts gears, and we swerve onto the sidewalk. We are not missing this party.

“This is what it was like 15 years ago, crappy parties in a crappy place with very good DJs. This is Antwerp,” offers Pieter Mulier along with a cigarette. He’s referring to my night out with Raf a few weeks prior. Mulier acts as his trusted right-hand at Dior, directing design across the Paris ateliers, especially when Mr. Simons is shuttling between the luxury megabrand and his own label. Thanks to a girlfriend who liked to dress her man in Raf Simons, Mulier discovered the label at 18. “It was all about tailoring and wool, an extremely modern view of classic menswear, the tight shoulder, the shrunken suit,” he remembers, and adds, “It was selling like crazy.” Mulier joined the menswear company in 2001, and while he seconded Raf at Jil Sander, he also kept watch over the Simons label four-to-six days of the week.

Mulier and I chat in a sunny courtyard in TriBeCa. Following Manhattan’s Westside Highway north from here, one can trace a path through the post-industrial landscape of New York’s by-gone club culture – from Area to Paradise Garage, and farther up to The Roxy and the Tunnel. Gyrating in the strobe lights with Raf and his crew the other night had awakened cranial vibrations, flashbacks to how songs like T.99’s techno anthem “Anathasia,” surfaced from the shadows in the early 90s, grating deeply enough that your molecular composition seemed to spin at the behest of the DJ. What perhaps mattered most to this trend that had little or no radio airtime, was the crucial support of the club space and its sound-system. Like reggae and dub before it, to call it a musical genre would be to miss its spatial dimension, a living social space where anonymity and togetherness were consensual pleasures.

“Scene” is a word Simons uses frequently, partly because his work is about so much more than garments. He says of his goals in the early years, “it also needed to be an environment, a mood that hangs around and that people inhabit.” Judging from the incredible locations at which many of his Paris shows have occurred, like the brambles of the Bois de Vincennes, or the reflective geodesic dome at the Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie, Simons is acutely aware of environment and context. This was again evidenced at a pop-up store for the Raf Simons / Sterling Ruby collaboration in Antwerp, which opened for a few weeks this September in a vast, feral-looking storefront that would be the envy of any squatter. There could be no better setting for a collection of heavy–weight peroxide-spotted wools along with thick, patched, wide-knit sweaters.

Simons can pin his decisive turn to fashion on a particular Paris Fashion week – Spring/Summer 1990 – when he discovered how a runway can become a completely immersive environment. While completing his coursework as an industrial designer, he interned for Antwerp fashion designer Walter van Beirendonck. At the time, Simons was attracted to fashion as a consumer, “If I could be dressed in Helmut Lang, I would do it all the way. I could buy a piece once a year and buy the rest at flea markets.” But he had not yet committed to becoming a producer. At van Beirendonck’s studio, Simons worked on showroom displays and invitations, such as “Walter Worldwide News: Fashion is Dead!” a faux-rag printed for that same Spring/Summer season. Beirendonck took him to see Jean Paul Gaultier. The show mixed cues from nunnery to cycling gear, spun together in a nightclub-like setting, with models rising from automated podiums washed in strobe lights. Impressive enough, but lightning struck when Simons saw Margiela. The show was staged out of a tent on a dusty playing field in a rough-and-tumble suburb of Paris. Neighborhood kids had been corralled to participate in the show. “I cried. I was so ashamed, ‘Fucking hell, why am I crying at a fashion show?’ I knew they were glamorous events from TV, but when I saw Martin’s show, I was nailed to the ground. It was so socially aware, psychological, and surreal. At that show I said, ‘That’s what I am going to do.’ But I didn’t tell anybody else. I didn’t tell my friends, Walter, my parents, nobody.” This kind of secrecy, a reclusive conviction, would characterize the first decade of the Raf Simons brand.

In the early stages of his career, it seemed to some members of the fashion press that Raf Simons relished in secrecy. New York Times writer Amy Spindler and International Herald Tribune chief fashion editor Suzy Menkes had reviewed Simons’ presentations as early as 1997, but Cathy Horyn remembers that, seven years on, her mental portrait of Simons still drew a blank. Horyn began reporting for the Times in 1999, but didn’t meet Simons until 2004: “I went to his shows and was intimidated by what I saw. I always thought that he knew so much about what was going to be cool, what was coming into the world. I was also kind of nervous. I had no idea what he was like as a person.” She had not given Simons serious coverage until History of the World (Spring/Summer 2005), a collection of nylon raincoats, silky sports shirts, and leather pants in glacial aerospace colors styled a la hip-hop. As Horyn confessed, it was a total conversion experience, “I beat it back stage like a kind of gaga person. It was really somebody trying to make a difference in fashion.” Why was it, she later wrote in her review of the show, that “out of a generation of so-called visionaries, only a few have Mr. Simons’ capacity to deal with the future in a believable way.”

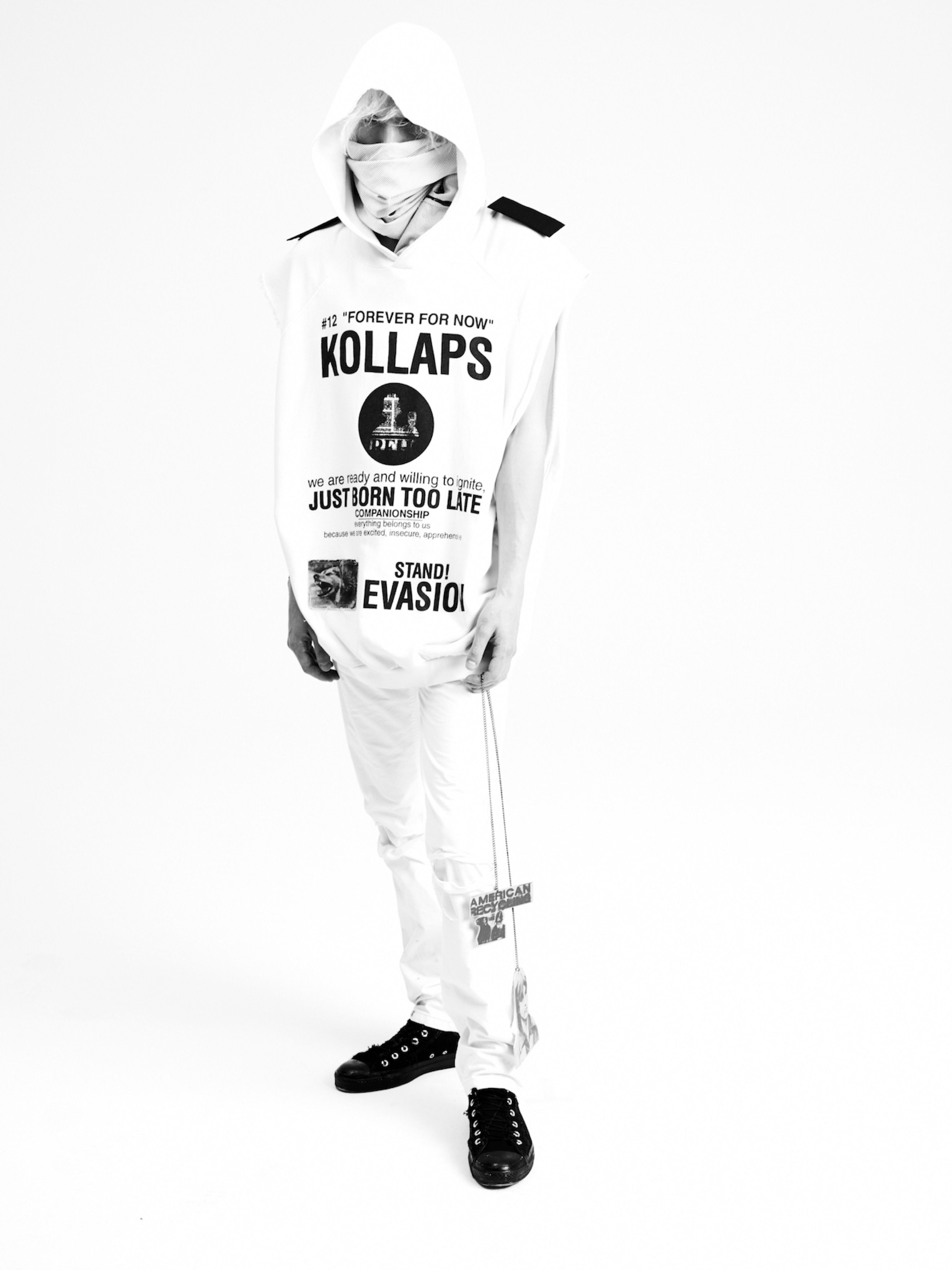

We do not know that we’re tired of what we have until fashion shows us why. In that sense, we assume the field has access to privileged knowledge. Horyn summarizes the Raf Simons man as a “guy who is super in-the-know,” someone who presumably, like the designer himself, deciphers the future of cool. Coolness, like the overplayed alienation of 70s punk, can often treat scrutiny as indifference. Coolness can be intimidating, simply because we feel caught in the cross hairs of judgment, as if the recalcitrant cultural scenes where cool is born lurk at a distance, keeping the fashion main stage under constant surveillance from the shadows. Simons’ collections, particularly until 2002, when he sent a bare-chested model in a basketball-net-turned-hoodie and a do-rag down the runway, have been by turns cool, unapproachable, defiant, and unsettling. Woe onto those who spit on the fear generation… (Spring/Summer 2002), a collection of loose sleeveless tunic tees, jump suits, windbreakers, hoodies, seems to make the theme of anxiety-inducing surveillance even clearer. Critics called it “terrorist-chic,” because the clothes, almost exclusively white and grey, had been styled to look like vigilante recruits, face wraps to boot. Applied to a lightweight windbreaker from the collection, a patch reads in bold red letters “BE PURE. BE VIGILANT. BEHAVE.” Presented nearly a year before September 11th, 2001, the words still seem to echo in the complex aftermath of the Arab Spring we are experiencing today. Whether the message is addressed to the audience or to the wearer remains unclear. What was evident, however, was that Simons was watching culture closely from the sidelines.

Fashion journalist Richard Buckley was someone who prodded Simons to step into the limelight, and argued it could be done without sacrificing integrity. He met the designer for the first time in April 1997, at Simons’ heavily attended, widely discussed second runway show, Black Palms (Spring/Summer 1998). Buckley recalls, “There was a beautiful, fluid, yet strict, silhouette. It was a little bit rock-n-roll, a bit post-punk, and a little bit goth. Everything about the show stimulated the senses and looked quite new. You really wanted to see men looking like that!” Suzy Menkes, who has followed Simons for the extent of his career, also remembers Black Palms, held in a cavernous cellar off Paris’ Place de la Bastille, an area known for its dive bars. It was a “teen-scene sort of thing,” she says, in which thin, wafer-chested boys marched down a concrete ramp to the drone of club tracks from Lords of Acid and others. It was adolescence in high resolution. In her review of Simons’ following collection, Menkes observed that he was introducing “a sleek new definition to sloppy street style.” Black Palms, Buckley adds, “was 100 percent fantastic,” but Simons did not appear following the show, an omission that became a trademark of his earlier years. Menkes chuckles as she recounts the one time Simons inadvertently stumbled out of an elevator and onto the runway, “I’ll always remember seeing his face in a state of shock that he found himself amongst us. At that stage, he never came out in public.”

As a whole, Belgian designers at the time seemed press-wary and reluctant to be photographed, Buckley explains, a posture epitomized by Martin Margiela, who was known to have made anonymity a central theme of his brand. In 1986, on assignment for the weekly menswear magazine DNR, Buckley had received word of a Belgian phenomenon on display at London’s Olympia exhibition hall, as part of the British trade show. That’s where he found John Galliano presenting his first commercial collection in a “decommissioned fire exit,” as well as the group of designers that were eventually dubbed the “Antwerp Six,” who, including Margiela, were all graduates of Antwerp’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts. In a widely successful attempt to restart Belgium’s industry of cotton, linen, and wool, The Institute of Textiles and Clothing (ITCB) had been instrumental in shaping and supporting the “Six.”

Initially, for Buckley, Raf Simons belonged to the same Belgian “revelation,” although he entered the fashion race almost a decade later. “We were hot on Raf because of the Antwerp Six,” he says of the buzz around Simons, which was mostly word-of-mouth. “It wasn’t that people were discovered and famous in five minutes,” explains Suzy Menkes, “it was much more private then.” That may be why Buckley felt strongly that Simons himself should brave the heat and appear in print. He proposed a profile of the designer and his then girlfriend, Veronique Branquinho, for HG (Condé Nast’s House and Garden), and traveled to Antwerp with a photographer in the summer of 1999, only to have Simons cancel the shoot.

Over the years, Simons has developed trusted bonds with the press, including Terry and Trisha Jones, founders of i-D magazine, Cathy Horyn, Tim Blanks, Jo-Ann Furniss former editor-in-chief of Arena Homme+, and Suzy Menkes, whose criticism did “freak” him out at times, “but only because she is really caring.” He reserves special admiration for Vogue’s editor-in-chief, Anna Wintour, who, Simons explains, has provided council at the most opportune moments. And yet, who can say that Simons’ reservations are unwarranted? After all, Manic’s guitarist Richey Edward had carved-up his arm during a press interview with NME magazine. That was the picture Simons used on the back of his sweater – “Back off!” So, what does Raf Simons think about the media today, waving gracefully after every runway show, posing for magazine covers, and being trailed by film cameras for the entire nerve-racking build-up to his debut collection at Dior?

“Once you give access, everyone needs to know more and more and more. I don’t like it,” Simons admits. “I got used to it, but I don’t get it. Why don’t bank directors have to talk to the press? If the press would disappear, I would be happier. It’s not because you are from the press that our discussion means more to me. But, of course, it does for most people. If some kid in the street tells me something about the collection, it means as much and sometimes even more, and sometimes it means nothing. What’s relevant is the constant energy and possibility of creating work.” On the dance floor with Raf Simons that night in Antwerp, I wondered about the source of his creative vitality. “I always liked a scene,” he says. “I like creating something that is not only about me, it’s about people who can relate to that thing and all together it becomes an environment. It was already happening before I even designed the first collection.”

The way he describes it, the Raf Simons brand sprung from his natural environment. He met photographer and filmmaker Willy Vanderperre, who has shot for Dior, Prada, Givenchy and nearly every Raf Simons campaign, at the Witzli Poetzli bar, nestled at the base of the city’s flamboyant cathedral. The Antwerp Six were in the air and “every conversation you had was about Belgian fashion,” Simons recalls, “which made me think a lot.” But he is quick to distance the notion he was reacting to the local buzz, “I don’t think I would have done things differently,” he speculates, “if I had been anywhere else in the world. What I was trying to do did not relate to Antwerp as much as it related to me and some people around me.” For Simons, a trusted posse provided a foundation of dancing until daybreak and hanging at the beach in Ostend, non-stop movies and New Beat, New Wave, and Dutch Gabber techno.

Fashion consultant and stylist, Olivier Rizzo, explains that Belgian music at the time was dark, a “normal Northern European reaction to the extreme excess of the 80s,” to the cramping effect of AIDS, nuclear threat, and the gratuitous violence of the Brabant Massacres. Known for two decades of campaigns and editorials, including heavyweights Prada and Miu Miu, Rizzo has lent his analytical eye and loyal friendship to Simons for even longer. It all translated, he says, into a club scene “of thick black holes, another world,” that he and Simons explored. As cultural narratives go, a similar action-reaction theory often explains the role of the Antwerp Six when some of its members like Ann Demeulemeester and Martin Margiela surfaced at Paris Fashion Week showing collections that had more in common with the somber and unprecedented designs of Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto than the bravura and panache of designers like Montana and Saint Laurent. More notably, perhaps, Demeulemeester and Margiela reacted by outing some of fashion’s unspoken codes, inverting layers, revealing frayed hems and stitches, incorporating actual vintage, and adding a dose of autobiography. It is through this reevaluation of codes that Simons’ first collections are related to the Six. Rizzo notes, “his first show was a complete mirror image of himself when he was a teenager, a 90s interpretation of the 80s Catholic school boys in the new wave era.” Suzy Menkes describes Simons’ early shows “as a whole scene of people like him and people he hung out with.”

Raf Simons can describe his generation’s fascination with music, particularly New Beat which he was “totally into” and it’s styling techniques, very precisely. “In my opinion, it was the last musical genre to be strongly connected to a strict dress code, like punk, New Wave, or even grunge. New Beat was a very specific way of dancing, of hair styling, a specific shoe, and lot of coats. After you got adaptations that were linked to Acid in London, where they would wear black Lycra, Spandex biker pants (really embarrassing, but you wore it, because that was the thing). If you had money, which we didn’t, you would wear a Jean Paul Gaultier wide-shoulder blazer with a narrow waist and six buttons. Most people couldn’t afford it, so you’d buy a cheap version. You would wear work-style metal-tipped Doc Martins with a big toe. We’d cut the leather away to expose it. You would steal hood ornaments from Mercedes and VW to wear around your neck. Kids in Belgium also created new codes. For example, they would steal porcelain portraits from tombstones to wear as accessories. It was a weird period.”

Pieter Mulier, whom Raf Simons picked out of a graduating architecture class in Brussels, learned the trade at the Simons studio, ordering buttons, working with pattern makers, and watching how Simons thinks about designing clothes. Mulier emphasizes that Simons is acutely aware of the accessories and maneuvers of cultural trends, “I always say that Raf is a stylist as well as a fashion designer.” Mulier explains, “Knowing all these extreme fashion and music references, whether it’s street or skate culture, to mix an odd reference here and there, is the job of a good stylist. Raf looks at everything.” Two persistent lodestones Mulier has heard repeated over the years, are Stanley Kubrick and David Bowie through his many avatars, including Aladdin Sane’s show-stopping outfits such as Kansai Yamamoto’s asymmetric body suit. Mulier describes Simons as an extremely visual thinker, “Pictures, movies, video, all thrown into a pot in his head and mixed until something comes out.” Simons’ stylistic mélange is deeply idiosyncratic, and though it smells like teen spirit, it doesn’t seem lifted from any textbook youth culture. Rather, it is a practice entirely rooted in his experience of adolescence.

Marieke van Dongen, a designer who has worked at Raf Simons for nearly a decade, tells me that, though the label is often equated with youth culture, that the term has become a kind of stigma, stamped in the early years and hard to shake. “The brand actually grew up a lot in the meantime,” she points out. Simons himself questions pre-packaged notion of youth culture: “I also think youth is not necessarily disconnected from intellect. When people define youth, they also only think about music and bands and going out, which is also annoying. There is so much in youth to investigate: your identity, pride, and vulnerability towards your environment. We sometimes talk about that more than the clothes.” The cartoonish distortion of marketing terms can make Simons’ early presentations look like fashion ploys. But, that would be to miss their sincerity and their ingenuity. Simons’ first four showroom displays, first in Milan and then in Paris, told their story through compelling music videos of adolescent lounging and loitering, scenes of Ouija board rounds, dressing-up, skateboarding, and cruising empty lots. Contemporaneous with Larry Clark’s infamous Kids, Simons’ videos like 16, 17 How to Talk to Your Kid, (Spring/Summer 1997) are close-up, prescient, masterfully edited, and very successful at displaying garments, a great example of his ability to make fashion look both accessible and edgy. Simons’ original goal was simple: “I was trying to make clothes that me and those around me were interested in, because it was the opposite of what we could find or experience in men’s fashion. In the beginning, I wasn’t planning on men’s fashion, I was simply working with limited resources.” Indeed, the cast of the videos relied on Simons’ crew of friends of both sexes, including Veronique Branquinho, blurring the lines between a showroom pitch and an autobiography.

“We talked a lot about pride and how to relate to oneself, ones persona, and the whole idea of the mirror,” Simons says of his design process. But you won’t find any mirrors in his Antwerp apartment apart from the bathroom, suggesting that he relies on his entourage and his work for self-reflection. Simons gives the impression that his brand remains in some vital way an alter ego, or maybe a trusted brother, a shoulder to lean on, maturing and remembering at once. Simons recent Autumn/Winter 2014 Collection in collaboration with artist Sterling Ruby is a case in point. Simons’ staff, and colleagues like Olivier Rizzo and Pieter Mulier, all claimed to see a resurgence of early Raf in the garments. They loved it. Mulier very enthusiastically admitted to buying the whole collection. Of the collaboration with Sterling, Simons says, “We wanted to connect strongly to a certain way of dressing and behaving that made us what we are now, that came out of our youth. For both of us, it was connected to music.” For Rizzo, “it showed how beautiful the merging of two creative brains can be.” The pair are close friends who met through Los Angeles art dealer Marc Foxx.

“We were very aware of the artist/designer collaborations from the past and we wanted to do something different,” Sterling explains. “We wanted to make our collaboration a true Bauhaus effort.” Sterling refers to the mutually reinforcing relationships between disciplines that were a major part of the German school’s modernist pedagogy. Raf Simons typically seeks that sort of synergy with artists. According to Foxx, he is not an impulse buyer out for quick inspiration. With a list of significant curatorial projects like The Fourth Sex: Adolescent Extremes (Stazione Leopolda, Florence, 2003) co-curated with Francesco Bonami, Guided by Heroes (Hasselt, Belgium, 2003), and The Avant/Garde Diaries – Transmission1 (Congress Center, Berlin, 2011), Simons has sustained a serious interest in artists like Vanessa Beecroft, Brian Calvin, Mike Kelley, and photographers Collier Schorr and David Sims.

Though Simons commissioned the interior of his first store from Sterling Ruby in 2007, and a pop-up at London’s Dover Street Market from Belgian artist Jan de Cock, his artistic collaborations are not designed to capitalize on promotional value. The collection developed with Sterling is personal. “Raf and I had an immediate connection when we first met close to ten years ago,” Sterling recounts. “We both have Dutch backgrounds and grew up in a small town rural setting. I think that we have a kinship regarding our upbringing, which more often than not seems at odds with where we both are now. It has led us to push each other in ways that we would probably not have done on our own.” Sterling had been making shirts and pants to wear in the studio using remnants of hand-dyed and bleached textiles from previous sculptures and paintings. Seeing this prompted Simons to propose a joint collection. The patches that appear on the co-branded garments, from medical prescriptions to orange tape, refer to the way both artist and designer had customized clothes as teenagers. About the patching, Simon says, “It’s like remembering. We don’t let go of our past. It’s very meaningful and attractive.”

Raf Simons is collaborative by nature. Marieke van Dongen was surprised when she started at the company as a 22-year-old intern that Simons would ask for her thoughts. “He values the opinion of people around him.” Pieter Mulier explains that collections usually start with hours and hours of discussion, without images, posing questions like “What is modern now? What do we feel?” And weeks can go by before clothes are mentioned, even if mood boards are present. Marc Foxx characterizes this thought process as an inherently open dialogue, “He circles something for a long time until he finds his way in and it’s always a personal, big idea, that other people can enter.” Fitting sessions reveal much of the way Simons works in unison with his team, fluidly cutting, pinning, and looking for reactions. He does not like to sketch, and if he does it’s a Post-it-sized memory aid. He is frank about his lack of interest in sketching, avoiding a dried-out stereotype of the genius designer: “When I draw, I feel I am doing it alone, and fashion for me is not an isolated activity. When you do a fitting – the model, the atelier, people around you – it’s a dialogue. I cut off, open, needle, and re-needle.”

Simons, who never went to fashion school, learned to cut and stitch by fabricating a test collection for Linda Loppa, head of the fashion division of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. Loppa was an instrumental supporter of Simons, whom the designer met thanks to Walter van Beirendonck. Her father, a respected Antwerp outfitter, agreed to coach the fledgling creator. With proof of his talents, she dispatched Simons almost immediately to his very first showroom presentation in Milan in 1995, for which he had to hastily improvise labels for the garments. Mulier tells me that the 40 women at Jil Sander’s Hamburg atelier also offered priceless knowledge of tailoring, from which he and Simons learned. According to Suzy Menkes, who has celebrated Simons for his “razor-sharp” tailoring (and called him out when it flops), his final three collections at Jil Sander were a break-through. They were “some of the most interesting collections that he’d done, because I never associated him with womenswear for a start or with couture,” she says.

Today, according to Mulier, Simons will correct everything himself during a fitting. The weight and handling of textiles is crucial to their process – la main. “We study how it folds, how the shoulder holds up,” Mulier adds. Marieke van Dongen concurs that tactility matters in the Raf Simons design process, where research of fabric can often define a collection. He expects no less of a hands-on, in-touch exchange with his collaborators, which I discovered when visiting his design offices in Antwerp where the work room floor is dedicated principally to space for fittings. Simons explains what he looks for in his creative team: “I need to feel that they have the guts to talk to me and say something I disagree with, otherwise they don’t stand a chance. I don’t believe in groupies. I don’t believe in the unquestionable evolution of one persona. People should question me and I question them. I’ve always been like that. I would not have started the Raf Simons label had I not realized that it’s something you don’t do alone. It wouldn’t be challenging otherwise.” The mood in his studio is focused but, relaxed and upbeat. Simons’ table butts up against those of the other designers, and is the closest to the fire-escape balcony – presumably a choice spot for a cigarette. I ask him about these sorts of things, the little pleasures and privileges of having your own brand:

RAF SIMONS: This is the best, thinking about my own brand at this moment in my life, having total freedom and independence and having it small. It gives you so much possibility. The landscape is structured around you and those with whom you work. You make decisions with these people, some of whom you’ve known for a long time. But it’s also a very heavy responsibility. I know that I am the one who decides what to make, and after 20 years, I know what’s going to sell. I never wanted to have that as a primary goal. I want to keep the conviction I had when I started in 1995, to make clothes because they feel interesting and relevant, because I am anxious to see how people respond. But you try to find a balance, and it only comes from a sense of responsibility. In Antwerp, there is the feeling and the fear of having to feed mouths. At Dior, I don’t have that kind of pressure, because I am one of their employees. It’s not my company. There, the challenge comes from scale and rhythm. It is a very advanced, industrialized company that communicates with so many different people. At Raf Simons, we do two runway shows a year, while at Dior it’s six shows, and there is nothing comfortable about it. I can only see Dior as a brand that I respect and challenges me, where I can try to do a good thing, to move it forward for a certain amount of time – like John did before me, and Gianfranco Ferré before John, and like somebody else will do after me. But I can’t think of my own brand that way. It is so connected to how I started.

PIERRE ALEXANDRE DE LOOZ: Do you think Bernard Arnault and Sydney Toledano chose you for the right reasons?

Yes. They wanted to modernize Dior. The dialogue is very open, especially with Sydney. Mr. Arnault I see less, but he is very emotionally involved, because it was the first thing he bought. It’s a father and child thing that I felt immediately.

Do you think Dior would have made as much sense to you without your experience at Jil Sander?

Dior became challenging and attractive because of choosing something like Jil Sander before, realizing how niche a thinking process can be. Bernard Arnault and Sydney Toledano never told me so directly, but they may have thought that I was someone who had the guts to believe in change, because it wasn’t so logical to do what I did at Jil Sander in the last couple of years, the volumes and color explosions that relate more to couture than original Jil Sander. And some collections were uber-feminine, some about how women relate to each other. There were reactions to the silhouette. And I was investigating couture and mid-century, Dior, Balenciaga, Givenchy fashion, because I felt trapped in an overly niche way of thinking.

Can you describe your thought process at Jil Sander?

I approached Jil Sander as an exceptional product about quality and durability, with a strong connection to minimalism (to which I could relate). I came to understand that it was also a regimented brand, in the sense that a woman had to wear Jil Sander head-to-toe. You had to be that kind of woman, wearing that kind of garment at that kind of social level. I questioned it, eventually. I wanted to liberate Jil Sander and connect it to the way women live now. When I arrived at the company, womenswear was changing worldwide and fast. Women were mixing a bag from one brand and a skirt from another, and that’s how fashion appeared in the magazines. It’s an evolution I had not observed before, and I found it really interesting. When I started going to Paris Fashion Week in my early twenties, one could still see the complete Margiela woman in the street, or the Yamamoto woman, or the Gaultier. I let control go as soon as the clothes appear on stage. I’m not saying companies do, but I do. I’m challenged when I see how garments are restyled and reinterpreted in the street or in a magazine. Sometimes it renews my inspiration. Sometimes, I have to admit, “Fuck, why didn’t think of that?”

How does the Raf Simons brand relate to you?

If I could be completely anonymous, I would. But, these days, it’s not possible anymore in fashion. Since working at Jil Sander, and especially since Dior, the whole thing is very global and exposed. It’s over-the-top exposed and communicated. And that’s not me as a person. It’s also not my brand. We don’t advertise. We simply put our clothes out there. I am very proud of it. I know for a fact that our business comes from press, journalists, and clients believing in the brand and not because they are obligated.

Internet media has really changed the way we pay attention to clothes. Is the constant Tumblr of images and cultures a threat, or is it an opportunity?

I’m not so interested myself, but I am interested that other people are interested. I have a huge disinterest in technologies that accelerate cultural speed. Immediately, they make me uncomfortable. When I think about the speed images are consumed on Tumblr it’s already not my thing. The way communication goes over the internet is not my thing. I can’t be positive or negative about it. But I’m fascinated by what society is becoming, and its evolution. I am watching the behavior more than the thing itself. I am not going on Tumblr to see what is going on. Not in my interest. I am more interested in mystique and romance, what’s difficult to find, aesthetics that are not in your face. When I think about images, naturally I am more attracted when I feel there is certain meaning, when someone is trying to say something. You have to investigate. You are prompted to investigate and understand, more than merely consuming the image. It’s how you judge looking at everything you see. There are things you immediately know are surface, and other things the opposite, and I’m more interested in the opposite. When you find everything so easily, you don’t look deeply anymore and you don’t investigate anymore. And you get bored.

Are you patient?

I think fashion made me very impatient and I hate myself for it. I am a long-term thinker and not in it for the short run so in that sense, I think I am patient. When it comes to love and friendship and the normal things in life, I think I am patient. Fashion, however, does not know patience. It’s an abnormal life. When I see friends who have nothing to do with fashion and discuss a collection that we presented six months ago, for them that collection has not really happened, because it’s still not in the stores. It’s very weird.

Traders move money within a fraction of a fraction of a second. It seems that’s what’s really setting the fashion clock. Is there any way out?

The question is: How can fashion decide for itself? I am very happy with where we are with the brand right now, and our freedom especially. To give you an example, I don’t see Dior or Chanel collaborating with someone who happens to be a close friend on a shared label, like I just did with Sterling Ruby. On the other hand, I see so many young people automatically buying into the fashion system as it is structured today, as if the individual can no longer do things differently. I really wonder if that’s going to be the real future of fashion. When I started, we were busy asking, “What are we really interested in? What attracts us? What can’t we find out there?” These days in fashion, the conversation is institutionalized. On the other hand, in the art world – which I’ve always been attracted to – an individual artist can still circumvent institutional structures, like the production schedules set by galleries and fairs. It doesn’t seem possible in fashion anymore.

A notion of home is important to you, it seems, like your brand is your home. How did seeing Jan Hoet’s 1986 show “Chambres d’Amis,” which forcibly co-opted 58 private homes in Ghent, affect your thinking?

Jan Hoet was a big name, and I was very attracted to it at 17 and 18. I visited it several times. Studying it years after, I realized that it was a mind-blowing idea. It placed everything in a very different context. The owners of each house let a different artist do whatever they wanted within the time span of a summer. It was open on certain days. It was a dialogue within a domestic context at a small scale, but with huge artists that you already knew by name. I still find it one of the most mind-blowing exhibitions I’ve ever seen it in my life, because the concept was so disconnected from an institutional context, which is as “pedestal” as possible. Our culture is all about pedestal – lifting it up, making it look more important than it is. Lately I talk about these things with Olivier Rizzo and Willy Vanderperre – they are my brothers. We are attracted to things that are not so pedestal, that are nowhere yet. I try not to judge anything as being good, or important, or interesting based on scale. What about Dior, you might ask? I’m interested in what Monsieur Dior wanted to do in those ten years, how he reacted to what came before him, not the scale of the enterprise. Had he been alive, I wonder what he would have done throughout the 60s, 70s, and the 90s. I go to a brand because of a strong interest in the original creator and his or her thought process and how that affects the people who believe in the brand. It’s not so different from what I do for my own label.

Is it possible to see Dior as an industrial designer?

It’s part of my fascination that he pioneered bringing fashion across borders, beyond the circle of women who surrounded him in Paris. He was, of course, a very French designer, brought up in a bourgeois environment with all its historical baggage. But he traveled to the US and dialogued with women there and started to think about what he could mean abroad. In that sense, he can be seen as an industrial revolutionary. Over those ten years, he was adapting the garments to the needs of very different women, cultures, and continents.

In terms of image, didn’t the New Look do for post-war fashion what the Cadillac did for cars?

It gave women the freedom to dress as they wished no matter the economic or social circumstances. It was a strong reaction against what was acceptable at the time – fabric had been rationed and had to be cheap. That’s why I think Dior still has so much impact. Thinking about it today, I love the idea that someone can kick the pedestal out from the establishment. But, what I hear from many of our generation – I think I am already one of them – is fear. I’m of the opposite opinion: Please stand up kids! But it’s only possible if you come out with a strong reaction. If you just want to fit in, yes, your business will flourish and you will become a big brand – that’s just the rule these days. But I am not sure what it will mean. Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo were a huge reaction at the end of the 70s. Maybe some of the Belgians had that kind of impact, especially Martin Margiela – if there’s a tradition you can connect him to, it’s the Japanese. Who was in charge in that period before Martin? Alaïa, Mugler, Montana, Gaultier, although he had that rebel attitude, whose optics were extremely glamorous. In one shot, with clothes inside out, girls that looked like zombies, and shows off in no-man’s-land, Martin kicked everyone else off the pedestal. It is only those moments that can define or cause a shift. A very beautiful thing about fashion is that it embraces difference. These days, with the exception of hardcore fashion lovers, it’s not so much the case. That’s why, in a way, I can still try with my own brand to show that you don’t have to follow systematic behavior, like with the Sterling collection.

Does fashion have a political side?

In the first five years, when I was becoming successful and unhappy, I really started thinking “What the fuck am I doing?” I started to doubt its meaning and relevance. Someone I know had to remind me of the fact that it’s something beautiful with which people identify and connect in a significant way. And I had to remember that before I got involved. I also had my fashion obsessions and they meant a lot. So, it’s not as if politics are foreign to me. You may remember the period when the Flemish Block took power in Belgium. We talked about whether we could do something at the company. I think this question over often. You have a voice and it could have an impact that can relate to important decisions.

Can you be honest with yourself about your own work?

If I don’t think something is great, I don’t make it. So, no, I don’t always see it, but others do. It’s all about dialogue, action and reaction. I’m in it to get a reaction. Again, I don’t accept people around me who don’t say what they think. I have a lot of doubts. Much of what I do comes out of doubt, fear, and feeling small and being a small-village boy with his brain somewhere else. I have a brain that has to express itself and produce, otherwise I end up in a nuthouse. It’s scary because it’s fragile. I need to bring it out and I need a reaction. Maybe it’s for confirmation? I don’t know. I am not a psychiatrist.

You use the word “psychological” a lot when you talk about the way you approach things. When you use it, what do you mean?

It’s difficult to explain in words, but it’s when there is a complexity that goes through the brain, the heart, and the persona. If those aspects relate to what you actually see in the context of fashion, then there is psychology present. I can see it in other designers. For me, it’s not always heavy. It’s automatic.

What does it mean to make a beautiful garment?

Maybe it has never been possible to think in terms of a single garment. For a very long time, the garment was just a tool to find a way of expressing certain things I had to say. Which is also why it couldn’t just be a thing sold off a rack. It also needed to be an environment, a mood that hangs around and people inhabit. It was only later that I realized “I am a fashion designer and I’m making clothes.” Perhaps when I started to work at Jil Sander, I started to think that in my own brand I might have jumped too far into content and concept.

Does beauty matter to the Raf Simons brand?

It’s difficult to explain, but we’re attracted to a certain kind of non-beauty, something raw. At Raf Simons, we’re after a certain attitude and intelligence, an audience with cultural awareness, causing a chain of reactions. The beautiful thing about the Raf Simons brand is that we’ve sustained an intergenerational dialogue. We’re twenty years in with some clients that grow old with us, but we still reach a very young audience. I like it for the same reason I like teaching, which if I’m honest with myself, is probably the most satisfying thing I’ve done. You can trigger a younger person to think and react. In that sense, our brand likes to direct itself to a younger generation. You feel there’s something in them that they don’t really know how to get out. And that’s how I myself garnered opportunity and benefited from support back in the day, through this kind of dialogue. For example, when I began showing in Paris, I found out that Dries van Noten, which was already an established company, was sending people our way. We’ve not talked about it, because we rarely meet, but I’ve never forgotten. It’s incredibly significant and beautiful for the older generation not to fear, but to educate, develop, and support the new.

Over two decades, Raf Simons has produced consistently varied and inspired takes on menswear, rooted in his own teenage paradigm of questioning, learning, and identifying. Masculinity for the Raf Simons brand is a notion of being constantly tested and not defined. It has run the gamut from the friction of school uniforms to the aggressive queerness of the Manic Street Preachers; from the swagger of 50s Mods to the brutishness of radicalized youth gangs; from images of gun-toting huntsmen to sexualized hippies, astronauts, and athletes. The narcosis of club kids and hormonal hooligans course through his many collections. Notably, the word “FATHERS” appears on the garments designed with Ruby – one word that seems to provide the ultimate litmus of being a man, everything that a boy desires and rejects. Ruby explains, “The word can be read in terms of history. It can be seen as questioning what role or identity contemporary men have. It is slightly alarming, and it fucks with current projections of masculinity.”

Fucking with current projections is something that Simons does with incredible acuity in his chosen medium, arguably better than the rest. Over the last decade, the Antwerp studio has operated as a veritable laboratory for the future shape of menswear, alternating slim and baggy, long and short with deft skill every season. The diversity of the Raf Simons approach to menswear, which remains consistently believable, makes his role in the controversial origins of the skinny-suit silhouette seem irrelevant (many believe the title of originator belongs to Hedi Slimane, now creative director at Saint Laurent). All of Simons’ friends and associates talk about the debate with knowing irony. For over forty collections, Raf Simons has brought intelligence, depth, and inventively expert tailoring to high fashion’s once very neglected stepchild. At least two generations of men can grow old without losing their cool. Men everywhere are lucky if Raf Simons continues to bear with the fickle and often delusional demands of the fashion system. But something tells me he cares too much to give up on us.

Credits

- Text: PIERRE ALEXANDRE DE LOOZ

- Photography: WILLY VANDERPERRE

- Fashion: OLIVIER RIZZO

- Hair Stylist: DUFFY

- Make-up Artist: PETER PHILIPS

- Lighting Assistant: ROMAIN DUBUS

- Photo Assistant: JORRE JANSSENS

- Styling Assistants: NICCOLO TORELLI, IANTHE WRIGHT

- Hair Stylist Assistant: LUCE TASCA

- Make-up Artist Assistants: KATHINKA GERNANT, MONIQUE VAN MOOTER

- Producer: FLORIANE DESPIERER @ 4Oktober

- Producer Assistant: WILLY CUYLITS

- Catering: CHARLOTTE'S KITCHEN

- Thanks to: HENRI COUTANT @ d'Touch Paris and STEPHANIE JAILLET @ TripleLutz Paris

- Models: LUCA LEMAIRE, LOUIS BAUVIR and JOLAN @ Hakim Model Management; JASPER, JOLAN, LANDER, LUCAS V, NICK, MATEO and SAMUEL @ Tomorrow is Another Day