Obsessions in Osaka: Unsound’s Mat Schulz and Gosia Płysa

|Shane Anderson

Riding in a taxi across Osaka, Unsound festival’s co-director Mat Schulz was talking very excitedly about DJ Sprinkles. Terre Thaemlitz (aka DJ Sprinkles) had recently released the widely acclaimed Resident Advisor mix, RA.1000 (2025), and was about to begin a four-hour set exploring the depths of house in Socore Factory, a small club on the other side of town. When Schulz, co-director Gosia Płysa, and I arrived, a note was on the door explaining a slight delay because of the typhoon, but the wet weather didn’t seem to bother any of local enthusiasts and (Western) foreigners, who were eager to see what Unsound Osaka was all about.

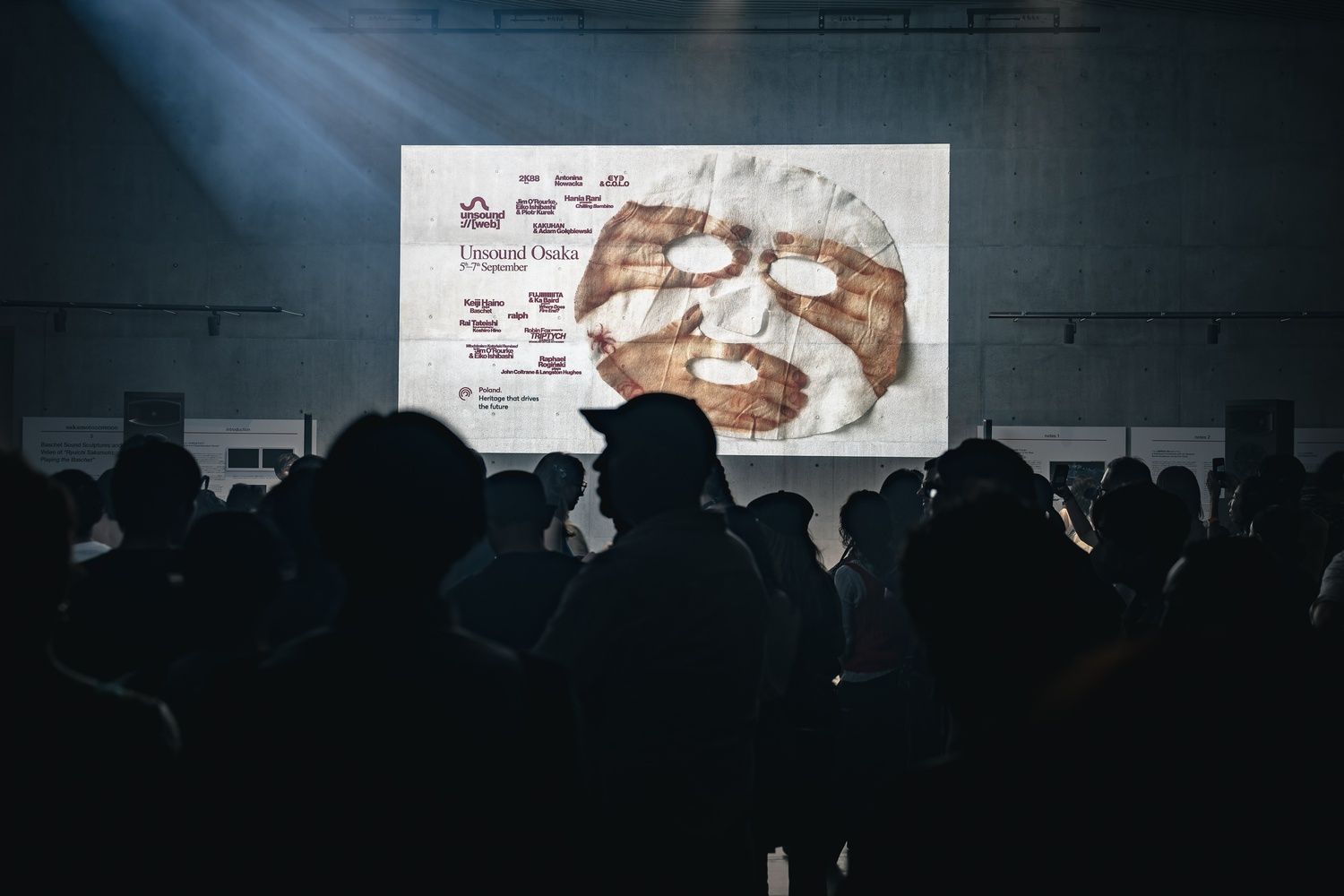

Unsound Osaka. Night One in vs. Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue

Osaka has always been an important city for experimental music. It is home to legendary acts such as Boredoms and Shonen Knife, as well as Japan’s take on gabber (called J-Core) and Japanoise. It is also the city that, famously, hosted the World Expo in 1970, where composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen and Iannis Xenakis debuted compositions alongside Fujiko Nakaya’s first fog piece and the Baschet brothers’ bizarre sound sculptures. With its history of experimentation that is raw, chaotic, and bodily, Osaka was the perfect city, then, to briefly host Unsound, the Kraków-born festival known for pushing music beyond genre and geography, where the likes of SOPHIE, Kode9, Death Grips, Richie Hawtin, VTSS, and many other envelope-pushers have performed.

Staged in dialogue with the Polish Pavilion at Expo 2025, Unsound Osaka unfolded across small, idiosyncratic venues and larger cultural institutions alike, pairing international icons with local innovators, and staging encounters that blurred the lines between concert, club night, and experiment. Highlights included Keiji Haino playing a selection of the Baschet brothers’ sculptures in the museum vs., Antonina Nowacka delivering an otherworldly performance in the Ohtsuki Noh Theater, footwork legend RP Boo DJing in the small club Circus, and ∈Y∋ (of Boredoms fame) and C.O.L.O. delivering a blistering J-Core audiovisual performance that was as hilarious as it was terrifying.

After the three-day festival concluded, I spoke with Unsound co-directors Mat Schulz and Gosia Płysa about the process of collaboration, Japanese attention to detail, and why club music tends to be conservative.

Jim O'Rourke and Eiko Ishibashi; Keiji Haino; Robin Fox at vs. Photos: Yoshikazu Inoue

Shane Anderson: You’ve done other festivals in 30 other cities. Why Osaka now?

Mat Schulz: We were invited within the context of the Week of Polish Culture organized by the Polish Pavilion at the World Expo 2025 in Osaka. We have always had a connection to Japanese music though, and dreamed of putting on Unsound in Japan. Especially in Osaka, which is such a vital city for all things on the more experimental side of the musical spectrum.

SA: Which, I’m guessing, is why you invited legends like ∈Y∋ from Boredoms.

MS: Yes, ∈Y∋ was essential considering his impact on Osaka. But we also invited Koshiro Hino, a younger artist who’s a very important for the local scene. We teamed up his and Yuki Nakagawa’s project Kakuhan with Adam Gołębiewski since that’s what Unsound has always been about. We don’t just present works that exist, we foster cross-border collaborations. The festival is a platform to commission new work. It’s a laboratory.

Gosia Płysa: And since we were part of the Pavillion of Poland at the Expo this year, we decided to invite some important artists from the Polish scene and put them in conversation with Japanese artists. We’re very happy with the result as there was a real synergy.

SA: So, that aspect of collaboration wasn’t unique to Osaka?

GP: Unsound Osaka is not very different from other Unsounds. It’s a completely different environment and culture but the idea remains the same. It’s about connecting the local context to the wider world. That’s why we called all the three editions this year that took place in Kraków, New York, and Osaka the “web.” There’s this overarching theme of connecting very different locations that have music scenes open to improvisation and experimentation. But we didn’t come here with set ideas and a package of headliners. We did a lot of research and collaborated with local curators, artists, and producers who understand the scene. Unsound isn’t a franchise that just plonks down with a program. It has to adapt to the place. I think that’s especially true here in Japan because Japan is so important for the kind of music that the festival represents and we’re doing it here for the first time. We’re kind of paying homage to that fact, and have thought very deeply about the program.

∈Y∋ and C.O.L.O. at Creative Center Osaka. Photo: Mikoto Yamagami

SA: How did Unsound begin?

MS: A friend and I started unsound in 2003. I was writing novels at the time, but my friend and I were both into the same kind of music and there weren’t really any festivals like that in Poland, or even Europe. And so, we started this little festival in medieval cellars in Kraków. We lost heaps of money. The second night, we even got thrown out of the club. The bouncers came on stage and stopped the whole thing.

SA: Why?

MS: Because they didn’t like the music. We had kind of suggested that it was a hip hop event, but it was heavily experimental. They stopped it halfway through.

SA: Sounds like a wonderful start to something that’s been going on for more than two decades. [Laughter]

MS: Yeah, we were like, “I never want to do that again.” But then some cultural institutions reached out to help support the second edition.

SA: How did you come into the fold, Gosia?

GP: I went to the festival privately. I was studying law at the time but was really into music. I remember it being an eye-opening event for me.

MS: The first night you came was a good one. There was Lucas Abela eating a piece of glass that was amplified—

GP: I was like, “What the hell?” It was amazing.

1729; RP Boo; Audience during the KAKUHAN & Adam Gołębiewski show at Creative Center Osaka. Photos: Mikoto Yamagami

SA: VTSS also studied law in Kraków and changed paths after attending Unsound.

MS: Unsound has ruined at least two law careers. [Laughter]

GP: Yes, that’s true. We share a similar pattern. But whereas VTSS went into DJing, I switched to journalism. I wanted to work in the radio and write about music. Then somehow the festival took over when I joined Mat and his friends to help organize the festival in 2006. Everyone was a volunteer at the time. But in 2008, Kraków was looking to promote the city through the festivals and we applied for some funding. You needed to be an organization though. That’s why we created an NGO.

MS: With this budget, we were able to realize bigger ideas we had. The little clubs in the cellars weren’t a good fit, so we started bringing sound systems into new spaces. Unsound really grew during this transformation process of Poland, moving from a state-centralized Communist society to the market economy that exists now. There were all these empty spaces in the city—factories, a hotel—and you could just go into them and put on a club event or concert. We also started using churches, synagogues, the philharmonic hall, and other concert halls. That became a big part of what Unsound is about: thinking about the city, its architecture, and history as part of the program. We think a lot about the interplay between architecture and music.

SA: You exhibit a very deep attention to detail and level of care. You even create extensive lists of restaurants and places to go for the artists and journalists coming to the festival.

GP: Maybe this is just something that comes with age, but I’m not really a fan of massive festivals with plastic toilets. We try to keep up the quality in every aspect, even in catering. This would be hard if we commercially expanded and grew in size—although there are still a lot of examples of well-done massive festivals. But we decided early on to focus on the growth inwards and focus more on the quality of the experience for the general audience—and ourselves!

MS: This time, we also wanted to put a spotlight on these smaller clubs in Osaka. They’re such idiosyncratic places. When I came on a research trip here, I went to some shows and there were literally four or five people in the audience. For someone in Warsaw or Berlin, they’d think the evening was a flop. Here, it’s not necessarily about turnout, especially for experimental music. Nobody expects a massive crowd. But we wanted to create a context for certain artists from Japan who might not always have a huge audience here, such as FUJIIIIIIIITA, but who has a big profile in Europe.

Ohtsuki Noh Theater. Photo: Shane Anderson

SA: Earlier you suggested that Japanese music is representative for Unsound as a project. How?

MS: People often ask what Unsound is and it’s hard to encapsulate in a single genre. The music always has a spirit of experimentation and desire to push the boundaries. Japan is known for that and they probably push it further than anyone else. But the music and concerts are often very carefully thought out. It’s not just, “let me do something freaky.”

GP: Sometimes when people come to Unsound, they’ll think that the artist is just trying to shock people. But I don’t think that’s what our artists—also the Japanese ones here—are trying to do. It’s not experimentation for the sake of it. It’s not gimmicky. It’s a serious endeavor. It’s a longer, explorative practice—

MS: Authentic is maybe a problematic word to use but Japanese artists are often very genuine in terms of what they’re trying to do. And they’re very focused.

GP: I think the “Japanese element” of Unsound is that kind of obsessive striving for perfection that you find in everything here from coffee to food to you name it. It seems to me that there’s a real honor here for performers or anyone else to present their skill to an audience. I really respect that. That level of diligence is why the result is so good and inspiring. And there’s also a sense of humility. You know you have to deliver. It seems to be a part of the culture here.

SA: Are you obsessive in the same way?

MS: I certainly am. I obsess over small program details—about the narrative of the night and how people in the audience will experience it.

SA: It’s not that different from writing novels.

MS: For sure, a lot of creative energy is put into creating a narrative. So, for example, if we’ve got more than one room, I ask myself: how does it work between these rooms? If someone is in one room for a while and then they go into the other one, I want it to work as an experience. It drives my program assistant mad. He’s like, “Just book something. This DJ, that DJ, whatever.” And I’m like, “No.” It’s about the design. The concept. How it all fits together.

Gosia Płysa and Mat Schulz. Photo: Kachna Baraniewicz

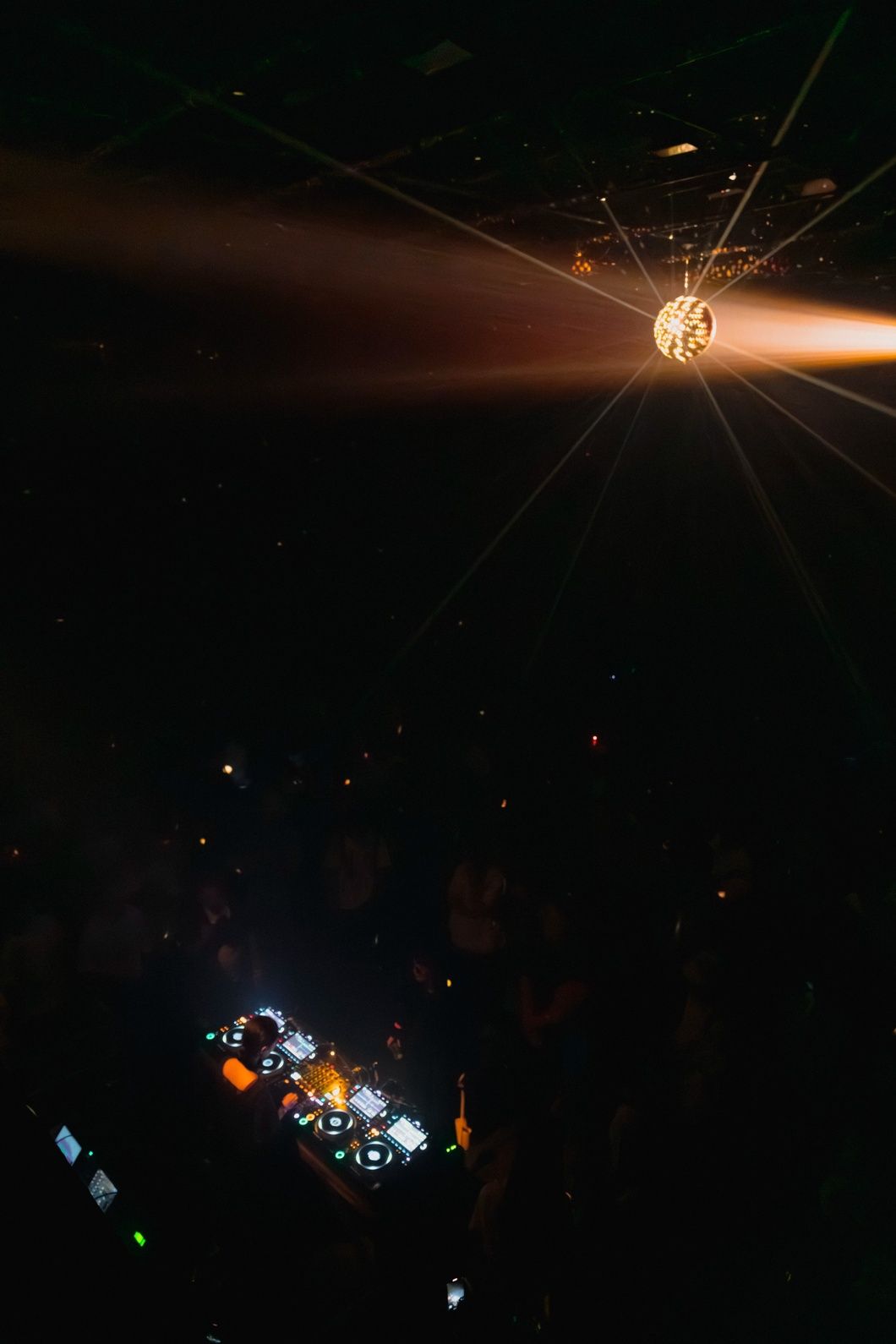

SA: We’ve talked a lot about the concerts but not really about the club nights, which seem to be equally important.

MS: The club music became a part of the festival from the second year on. In Kraków, we have a big space where everyone comes together to dance and what have you. But the way those nights happen now, we don’t just have club music. We mix live performances and interventions to play with the idea of club music, which can be, ironically, quite conservative. I think people really love it when you mess with that. If you choose the right thing, you can build on the euphoria of the moment in unexpected ways. Last year, for example, Keiji Haino played a short noise guitar show at 1am between rhythmic club music, and it was perfect. It’s one of my favorite parts of programming.

GP: There are really interesting things happening on the fringes of club music. We like finding those pockets of genres that haven’t been named yet. For a long time, we were really inspired by East and West African dance music and then with baile funk from Brazil.

MS: The one thing about club music is that it quickly becomes dated.

SA: How?

MS: I remember having a club night in 2008 called Dubstep Invasion, with Skream and Benga. Imagine giving an event that name now. Industrial techno once sounded edgy, the pandemic somehow broke deconstructed club music, and so on. Then there were all these edits and now…

SA: What’s going on right now?

MS: I’m not sure the club is the place where the most interesting music is happening right now, but it’ll change, and we’re listening.

Credits

- Text: Shane Anderson