NikeLab x MATTHEW WILLIAMS: My Body, This Computer, This Fire

|Thom Bettridge

Is working out a subculture?

“No,” Matthew Williams says. His tone is point-blank, but also somewhat tentative. Since his days as a creative director for Kanye West, Lady Gaga, and the oft-mythologized streetwear collective Been Trill, the California-born designer has become a global expert on how subcultural ideas flow through the fashion industry. His own brand, ALYX, is heralded for its finely tuned luxury interpretations of goth, streetwear, and military lexicons. Fresh off a transatlantic flight from Los Angeles to Milan for Salone del Mobile, Williams takes a moment to reconsider the question, drag on his double espresso, and edit himself. “I think certain forms of exercise can be a subculture. But there’s tons of people who have working out ingrained into their day-to-day life. Like eating. Or sleeping. Or breathing.”

For an NDA-encrypted time span, Williams has been working with Nike to help capture the bodies and minds of the ever-expanding “training” category. Since the tidal wave of the “Athleisure” lifestyle craze, the idea of what “training” actually is has become increasingly amorphous. The search is on for an athleticwear skeleton key that can unlock the gym-work-leisure complex. Moving toward a new form of clothing that reflects the performative and aesthetic demands of the contemporary arena, Nike has asked Williams to see what kind of designs he can make using the multinational’s big data infrastructure. At the company, this technology is currently active in two main directions: through the Atlas Program, a body-mapping database that tracks how athletes’ bodies move and release heat, and through Nike’s “generative design” initiative, which uses machine-learning algorithms to create design solutions that can respond to these heat maps as well as pioneer low-waste patternmaking.

What exactly is the Atlas Program?

Kurt Parker (VP of Apparel, Nike): Although we’ve been working with athletes in many, many different sports for 20 or 30 years now, a lot of the information we have is conversational and anecdotal. We realized that we didn’t have a way to take what we had learned out of the Nike Sport Research Lab and make it available to our designers. So, about four years ago, we started the Atlas Program. We began by asking: What do we do with all this data? We’ve got climate control chambers and aerobic equipment so that we can understand what the body is doing in almost any sport, like: “What does it take to warm up for football? What does it take when you’re going for a run? When does your body hit that optimum temperature? And when does the body start to sweat?” What works in the spring is obviously not going to be the same in the winter, but what’s unique is that the body drives to keep conditions stable no matter what the external variables are. Atlas lets designers pick a sport, or pick a climatic activity. For example, it’s cold outside and the activity is aerobic, like running or training. Then they can layer on variables, like what happens when it starts to rain, or when the temperature drops but your body temperature increases. These things are all visualized. Imagine looking at a mannequin avatar to see exactly where the body really heats up.

At the earliest stage, the mapping pointed to the center of your back, up by the neck. We found that the heat released from this area functioned like a dog panting when it’s really hot out. So thinking about breathability in that area became important. Information like this dispelled a lot of prior beliefs. I think everyone assumes that under your arm is where you need the most breathability, and while it’s true that you generate a lot of sweat there, the armpit doesn’t actually do a lot to regulate your temperature. Whenever you find a way to visualize data, it lets you solve the problem differently, and also starts to inform an aesthetic. These maps are like the weather report: It’s always interesting to see where it’s hot in the world, and where’s it cold. With the color variations, you can visualize how the Earth is cooling and warming itself. The same thing happens when we put our data on the avatar, so it started to inform the design language for us. If you follow the data itself, you can end up with a lot of things that look interesting, but maybe aren’t all that interesting to wear. That’s why doing this project with someone like Matthew Williams is great because he was challenged to do something with the data that we might not otherwise have done.

We’re at a point now where we can start to combine layers. When we talk to athletes, they say it’s actually the cling of the material on the skin that’s more uncomfortable than the fact they’re hot and they’re sweating. So the importance of airflow and anti-cling became a much more interesting problem to solve, because if you can increase the airflow around the body and try to keep the material from directly adhering to your skin, the body actually cools faster than it would through evaporative cooling. We proved that recently when we launched the NBA jersey. The guys were like, “Hey, the thing that slows me down is when my uniform starts to get really heavy with sweat.” So we developed these nodes on the interior of the face that you don’t really see from the outside. They help lift and create a little bit of space through which air can flow, so even though they’re playing at an intense level, their uniform is lifted away and accelerating that evaporative cooling effect.

Then we can put the avatar into motion. Instead of looking at a mannequin, you can actually see what it will look like when a soccer player kicks a ball. You can freeze it and move it. When we first got the Atlas Program rolling, the models were very static, but when we added motion to it, things like material deformation, or material modulation – where it needs to stretch and where it needs to contract – all of that could be visualized by the designers as well. Suddenly, you could not only see where the body was heating up, but also where the tension or stress on the garment was. It was all about taking the data that we’d been building over the last ten, fifteen years – since we’ve been more in the digital space – and putting it on every designer’s desktop. So when they start a project, they’ve got the data of thousands of athletes at their fingertips.

“They really just gave me the keys to the Ferrari and asked me to take it to the limit,” Williams says, putting it bluntly. Yet, while one could say the Nike executives were letting Williams take their computers for a spin, there was clearly much more deliberation at play. At its debut, ALYX became famous for its use of military design in the context of luxury womenswear. And Williams himself is quick to identify the fluid continuum between the athleticwear industry’s performance-based methods and the utilitarian design legacy of military clothing. “The overlap is functionality,” Williams says. “Both need to work for the given action for which the clothes are made, which can sometimes be broad.”

In reality, Williams is one of the few designers in the world capable of stress testing the aesthetic boundaries of Nike’s methodologies. At a relentless rate, the Atlas Program and its accompanying big data technologies are capable of churning out endless design iterations. Many of these iterations exist firmly within the scope of what already exists, or what is much too bizarre to be offered for market consumption. But for those things on the borderline – for the strange yet not utterly alien forms that in the pre-big data world would have been called “avant garde” – Nike has recruited Williams as a type of high fashion soothsayer, an oracle able to identify the shapes that sit on the edge of what is wearable at present.

In a way, you could say that this collaboration was between you, Nike, and a computer, not just you and Nike. What did this three-way neural handshake feel like?

“It blew my mind how creative the computer could be,” Williams remembers of his time in Beaverton, Oregon, at the Nike World Headquarters. “We as human beings need to find ways to apply this information that the computer is generating, to use it to solve certain problems. But a lot of the time, the output reaches much further than my mind can see, and it brought me to new solutions. The experience really showed me how our lives are going to become more intertwined with technology as we move into the future.”

At a time when conversations are cropping up across many industries about the role humans will play in an automated future, Nike and Matthew Williams’s project is a test case for a human-computer creative collaboration. Whereas the Atlas Program’s software is able to deduce, for example, that a portion of the upper back is crucial for releasing body heat, the software is not capable of identifying what design response this information necessitates. It could churn out a shirt with a hole in the upper back, but it is likely that no one would buy it.

“Many of these computer-generated designs really do telegraph a heat map or something,” Kurt Parker admits over the phone from Beaverton. “And within a matter of minutes, the program will give you hundreds of variations and options. So there is a process of saying, ‘I’m not sure why, but I like that one and I’m going to save it.’ Sometimes you might want to let the data skew your aesthetic. Other times you might want to manipulate the aesthetic a bit to express something that has a relationship to the problem you’re trying to solve. It’s really about finding that balance point.”

In practice, the process of working with computer modeling and digital avatars is one that resembles editing much more than traditional design. Finding these types of “balance points” – moments where familiarity and metaphor allow the alien to hinge into something intelligible – is a core pillar of design practice. It is a skill set that far predates big data, but it may be the only skill set that matters after it.

So far, the more extreme fruits of Nike’s generative design program have trickled onto the market in controlled ways. The Nike Zoom Vaporfly, a mass market running shoe designed specifically for Nike’s moonshot project to help an athlete break the two-hour marathon barrier, features an uncanny heel shape that was conceived via computational design. When long-distance runner Eliud Kipchoge failed to beat the marathon world record in Berlin in 2017 while wearing the shoe, he suggested that water absorption had slowed him down, prompting Nike to develop a new upper using Flyprint, a plastic filament that unwinds from a coil and is constructed in layers by a 3D printer. Just a couple months later, in September 2017, NikeLab launched the Nike A.A.E. 1.0 t-shirt, a garment that merged Nike’s heat-mapping and knit-patterning technology. Its goal was to correct the disadvantages of wearing one t-shirt all day in the various micro-climates one passes through in everyday life. This algorithmic remake of a deceptively simple design was a major departure point for Williams’s work with Nike. However, in order for more of these computer-generated designs to become mainstream, human designers must act asconduits, translating new forms into an intelligible cultural lexicon. “I think humans will always be great storytellers,” Williams says. “And this storytelling will be necessary for providing an organic texture and figuring out how a design applies in our lives.”

Of course, the idea of a “human touch” that is safe from AI feels more and more like a vague platitude. However, to put it more coldly, there are human capacities for allusion, anecdote, and irony that remain vital ingredients for integrating new ideas and shapes into the flow of the market. An example of this from Williams’s first release with Nike is a small yet elegant act of détournement: a white sock that looks like it is sewn into a black sock.

Tell me about the sock.

Matthew Williams: This double sock thing is something I had seen basketball players do. It’s just one of those things that I would want to wear. I love that it’s playing with something so mass. In the same way that Hanes owns the white t-shirt, I would argue that Nike owns that athletic crew sock. Everyone owns a pair of that sock, either in black or white.

I’m wearing one in black right now.

I am too! So it was just this idea of like, “Let’s play with that. Let’s play with this iconic, utilitarian item that everyone has.” And to be able to have my hand in that and touch that design was amazing.

Sold in three-, six-, and 12-packs across the world, the ribbed Nike Crew Sock is a universally recognizable readymade. Its form says to large portions of the population “sock” in a way that feels deeply Platonic and elemental. Understanding the place this item has in the collective conscious, Williams created his sock as a kind of uncanny magic trick, one that cements the unexpected use of an industrially made item. Making a permanently doubled-up sock honors an entire history of sportswear, which has evolved through vernacular, user-generated alterations. What we know now as the “sweatshirt” is the cut-off top of what was originally manufactured as a onesie for women. Nike’s famous two-in-one shorts, with built-in compression underwear peeking out from below, was adapted from the style choices of runners and basketball players. In order to create his sock, Williams had to consciously or unconsciously call upon anecdotal knowledge while understanding the delicious irony of reference-flipping an iconic design. These are gestures that Nike’s supercomputers are currently unable to replicate.

There is an unconfirmed saying that in the tradition of Amish quilting, quilt makers will purposely insert one block that disrupts the pattern of their quilts, called a “humility block” because it is placed to recognize that only God can make something perfect. Throughout Williams’s collection with Nike, there are numerous humility blocks, not exactly mistakes in service to the heavens, but small acts of frivolity that reflect the fact these clothes were not solely designed by a computer. For example, the collection’s sports bra, which has a not quite functional-looking buckle across its upper chest, faintly echoes the harnesses found in the techno club scene, a recurring inspiration in ALYX’s collections. Williams, on his part, is tuned in to the psychological texture of garments, even in the context of heat mapping. “Temperature has a lot to do with thought control,” the designer says. “A friend was telling me how they keep airports at a certain temperature to make sure everyone is very complacent. They also do things like making sure SAT testing rooms are cold so that test takers can concentrate.”

But why focus these ideas toward training?

Matthew Williams: Training is this really large thing that millions of people participate in. Every sport prepares by training in some way. And there’s this growing idea that training clothes can be something that people go about their day in, too. So the concept was: to the gym, at the gym, after the gym. I wanted to create a collection that could work on all those different points, led by the data we had.

Kurt Parker: We want to accelerate the aesthetic of training. We know that a lot of our training customers live in densely populated urban areas. And it’s a sport that can exist in your day if you make room for it. If you’re working, it might be at lunch. If you’re a student, it might be before or after school. People are now literally training instead of going out to bars as a way to meet people. The versatility of the apparel, being able to move through your day and evening without having to roll a luggage cart full of outfit changes, is something that needs to both function and look good. There are a lot of transitions. The warm-up. The activity. The cooldown. In urban environments with air conditioning, you can undergo 20-degree temperature swings just by leaving or entering a building. Those are some really exciting design problems and design opportunities, and I think Matthew has the ability to approach this with the utility of his designs. It was just a really natural connection.

Matthew Williams: I’ve heard that a lot of times fashion people come and will be like, “I want to make a dress out of Flyknit.” And, yeah, that’s cool. That can be really beautiful. But what’s the purpose of that? What problem are you solving for an athlete? Why does this thing deserve to exist?

With the further development of big data and machine learning, the boundaries between the human mind and body are being negotiated in a way they have not been since Descartes wrote his Meditations nearly 500 years ago. What importance do bodies have in an economy dominated by cognitive labor? Is technology here to help human beings live more richly in their minds, or does the body contain certain forms of knowledge that need to be appreciated in order to self-actualize? In a future where many jobs will be replaced by artificial intelligence, will the body take on a new importance? By developing its training category as a site of innovation, Nike is addressing the needs of contemporary urban professionals using the very same technologies that might one day replace them. This begins by dissolving the barrier between life and training.

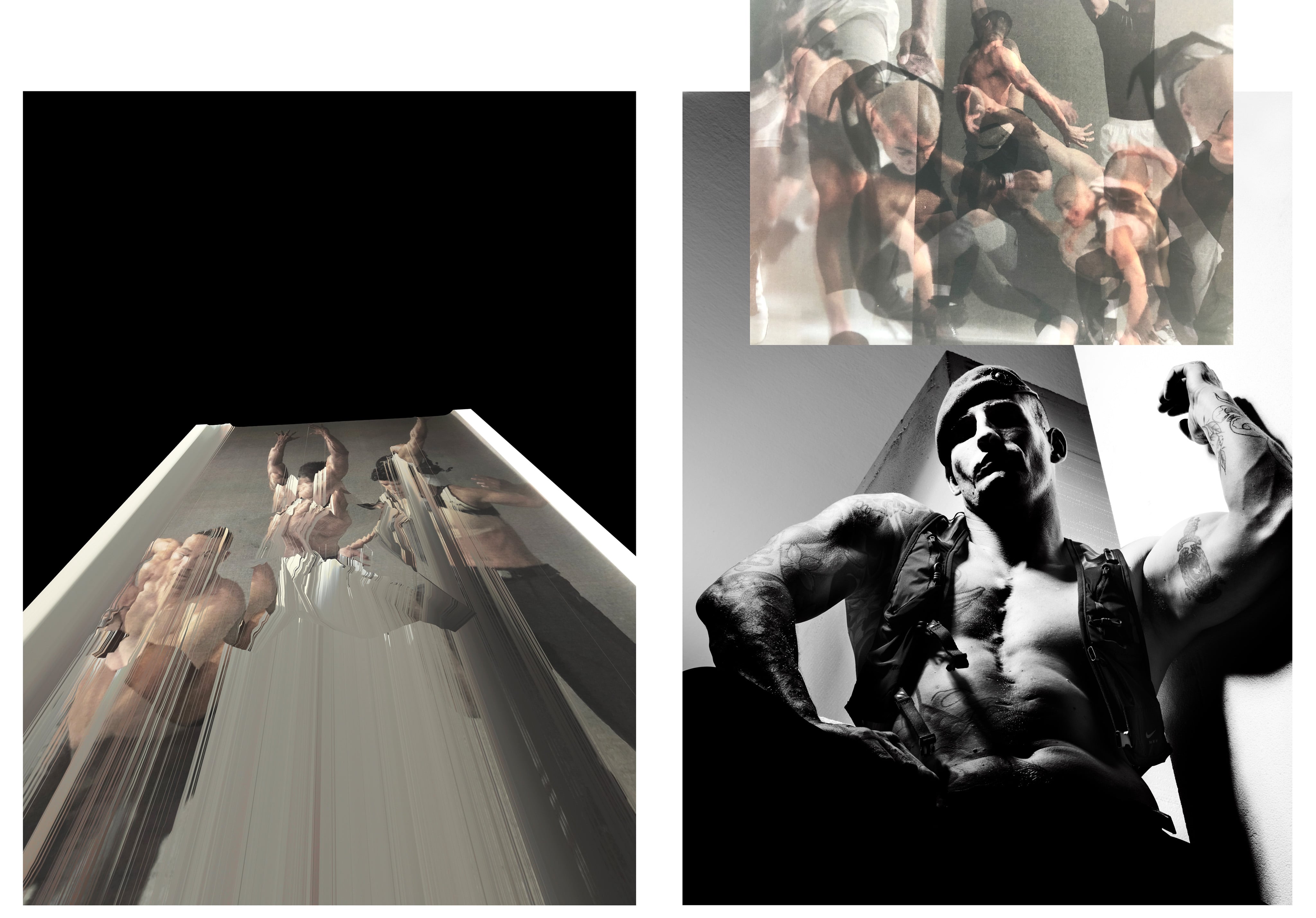

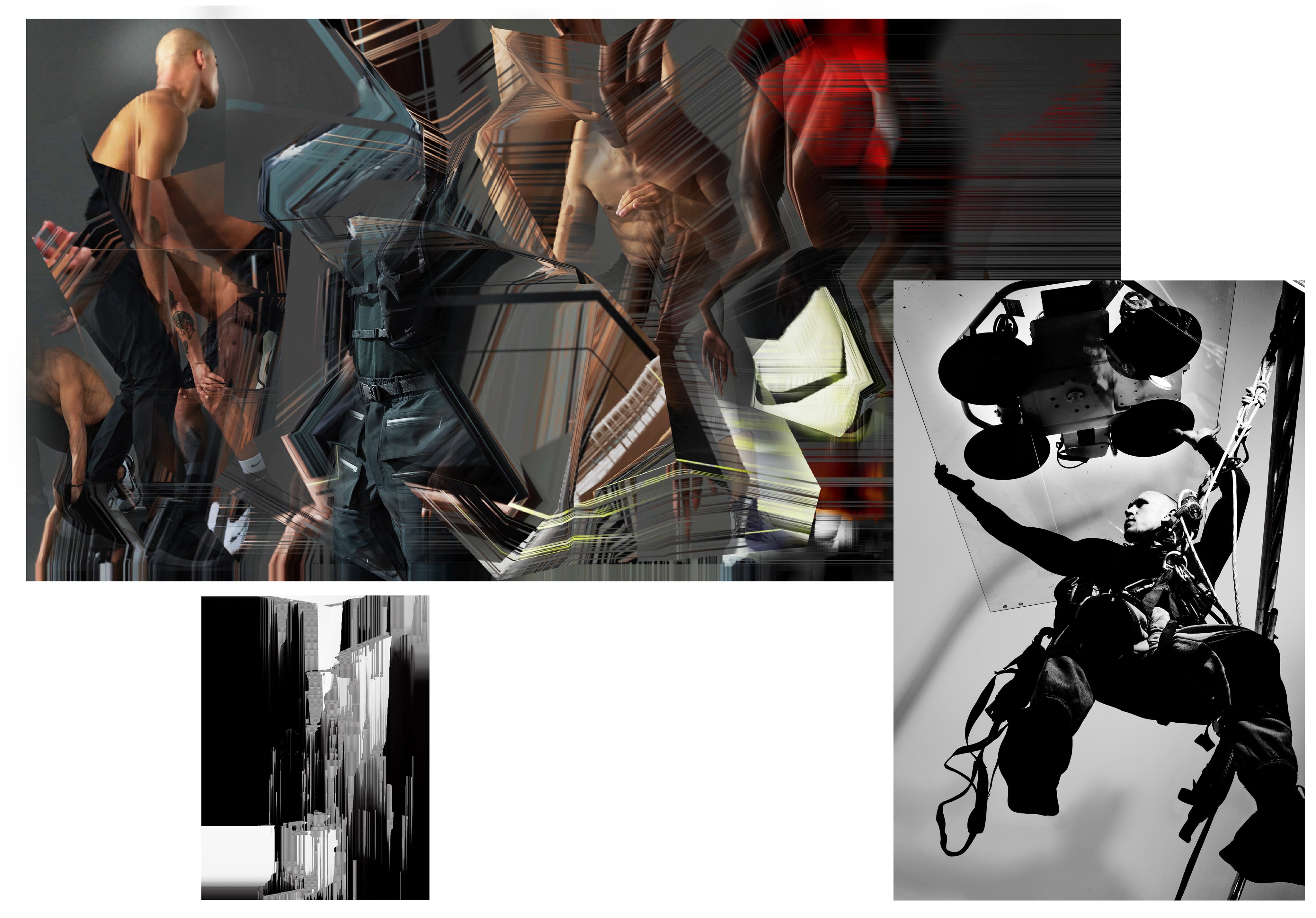

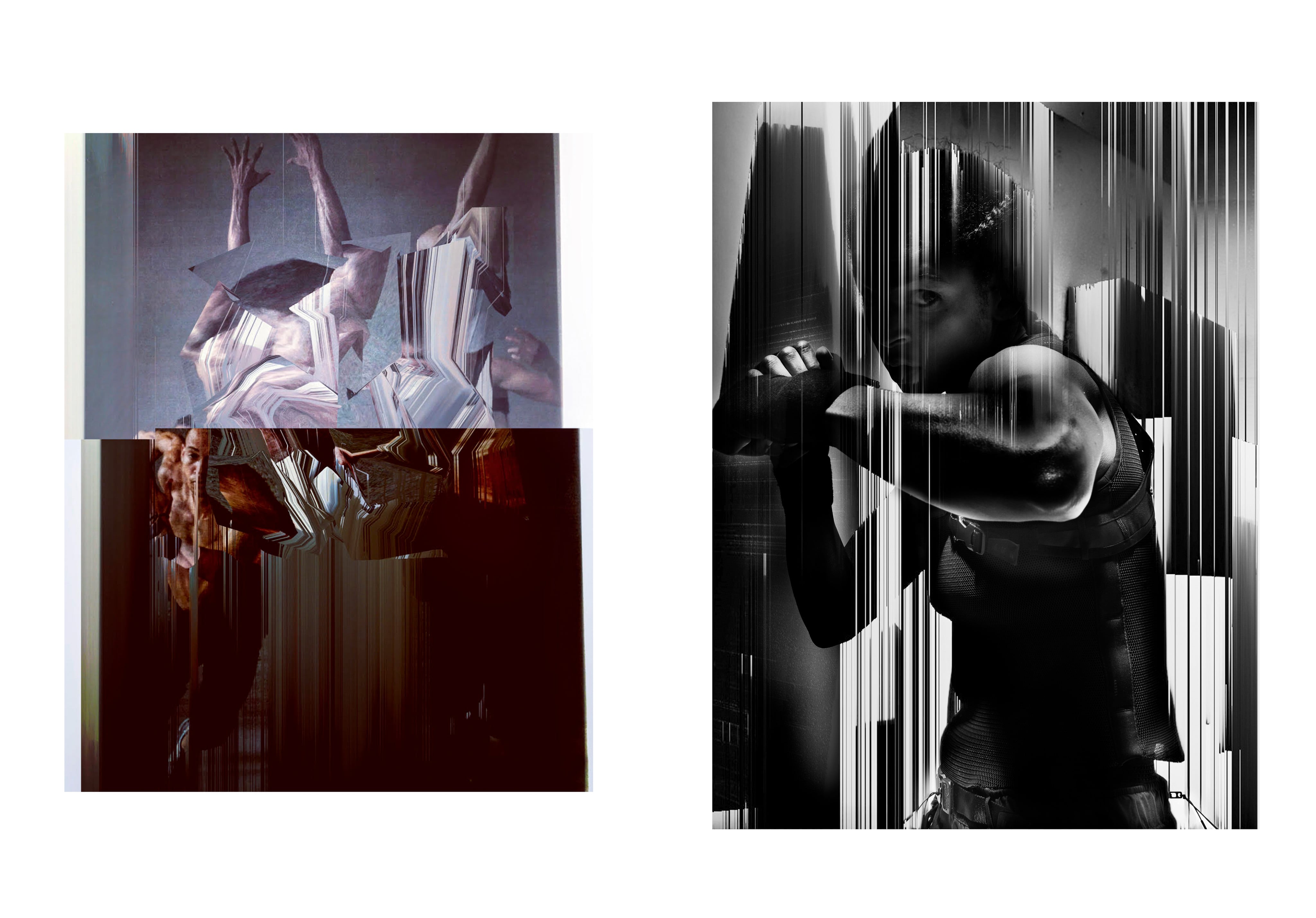

Credits

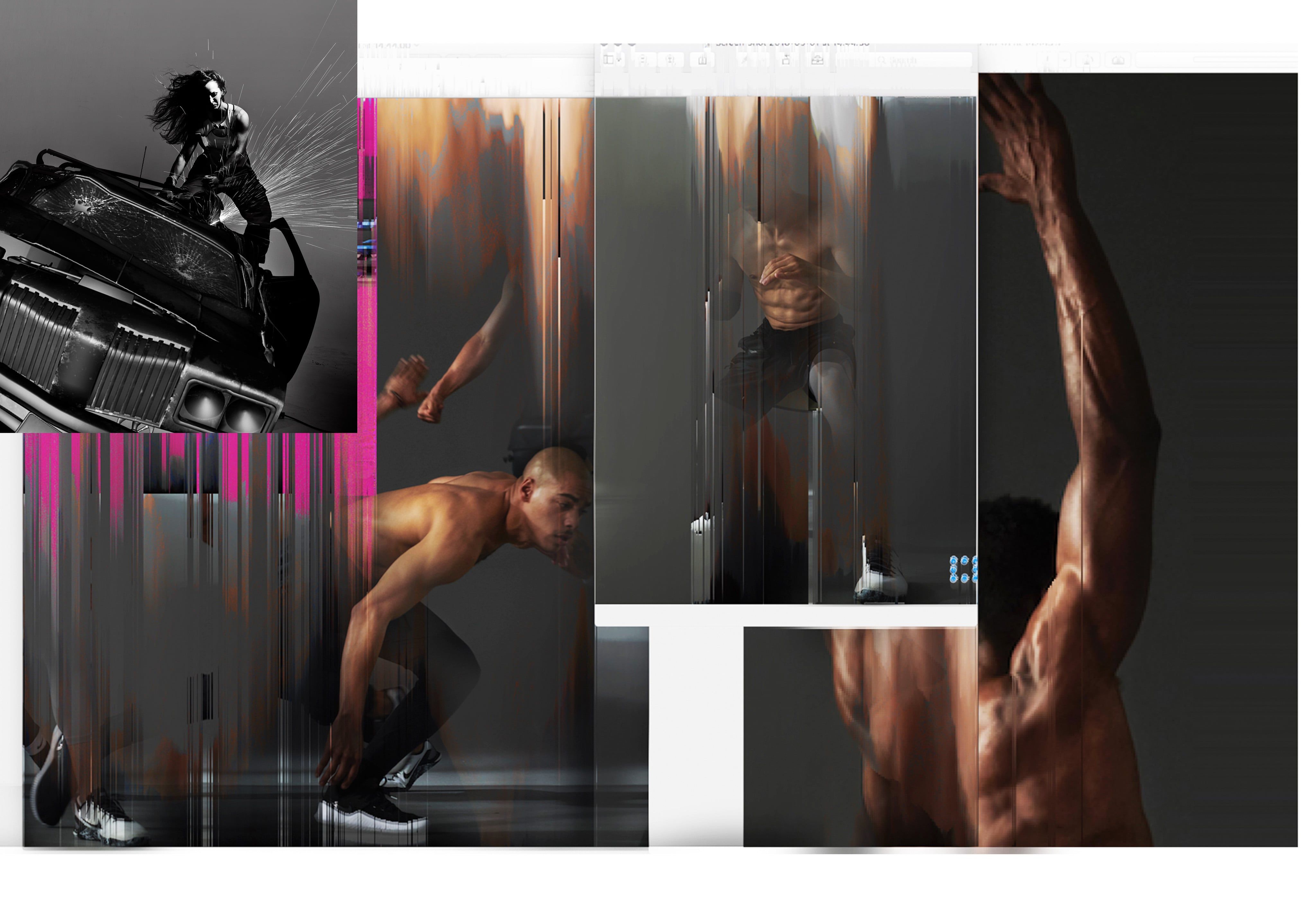

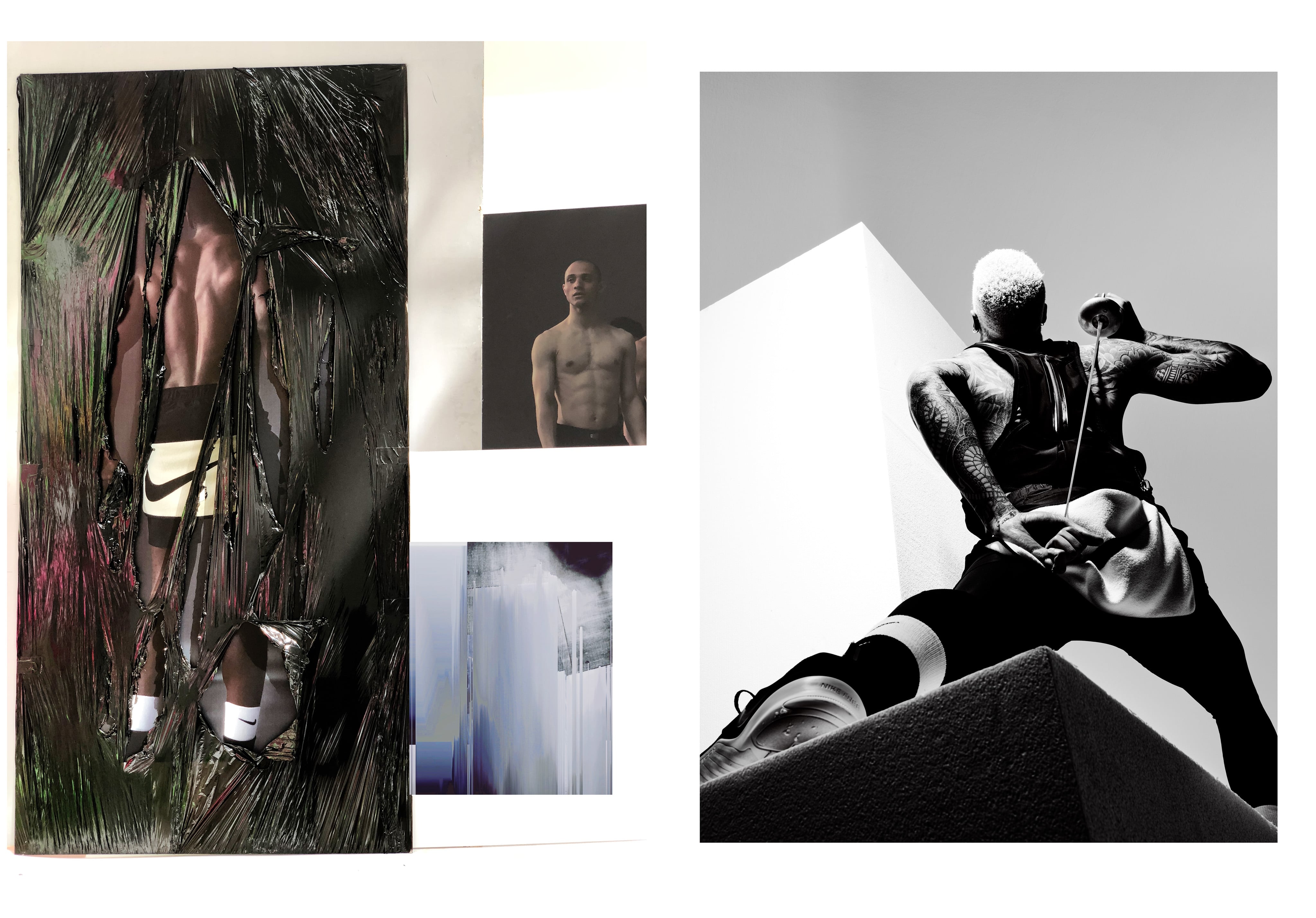

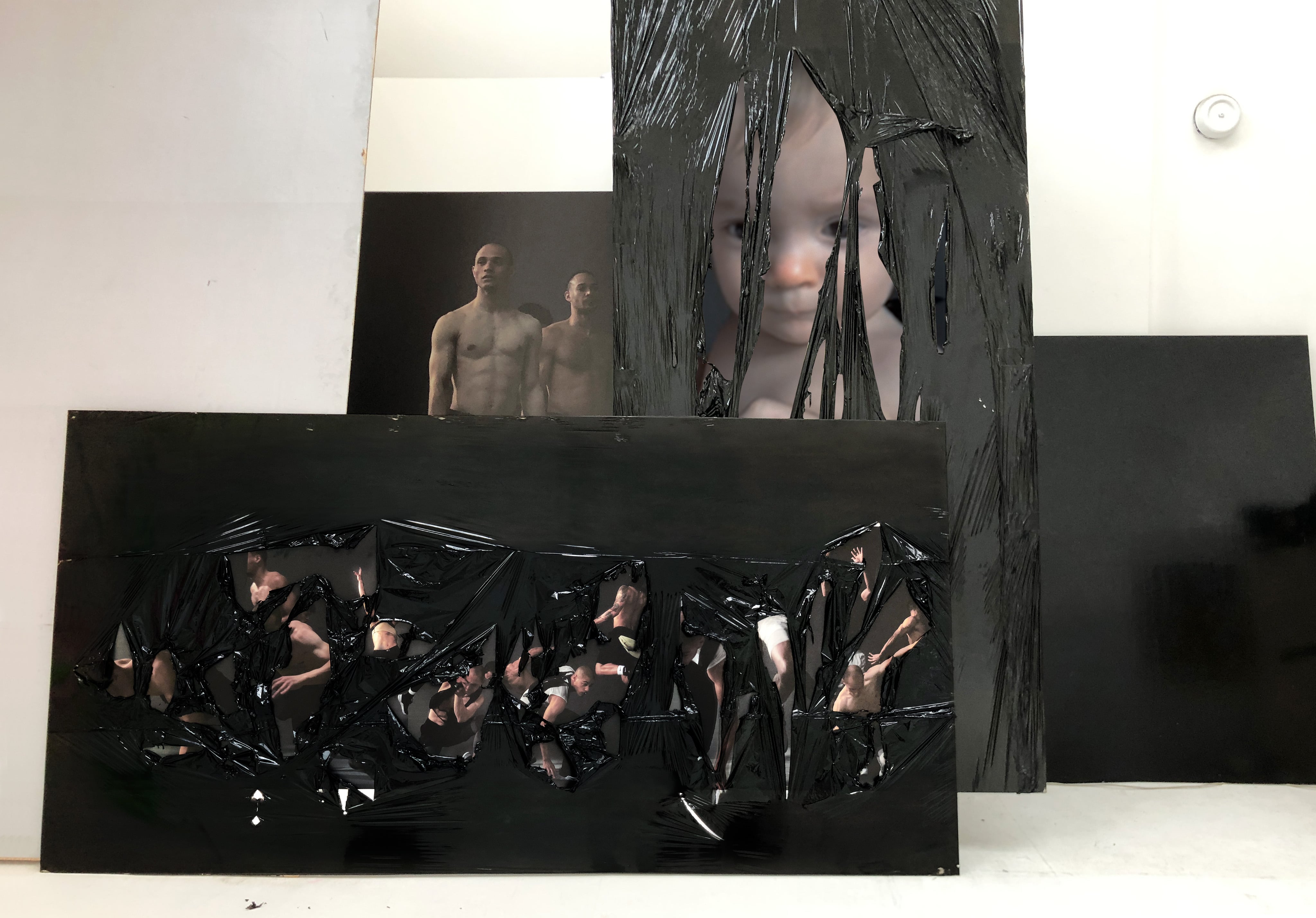

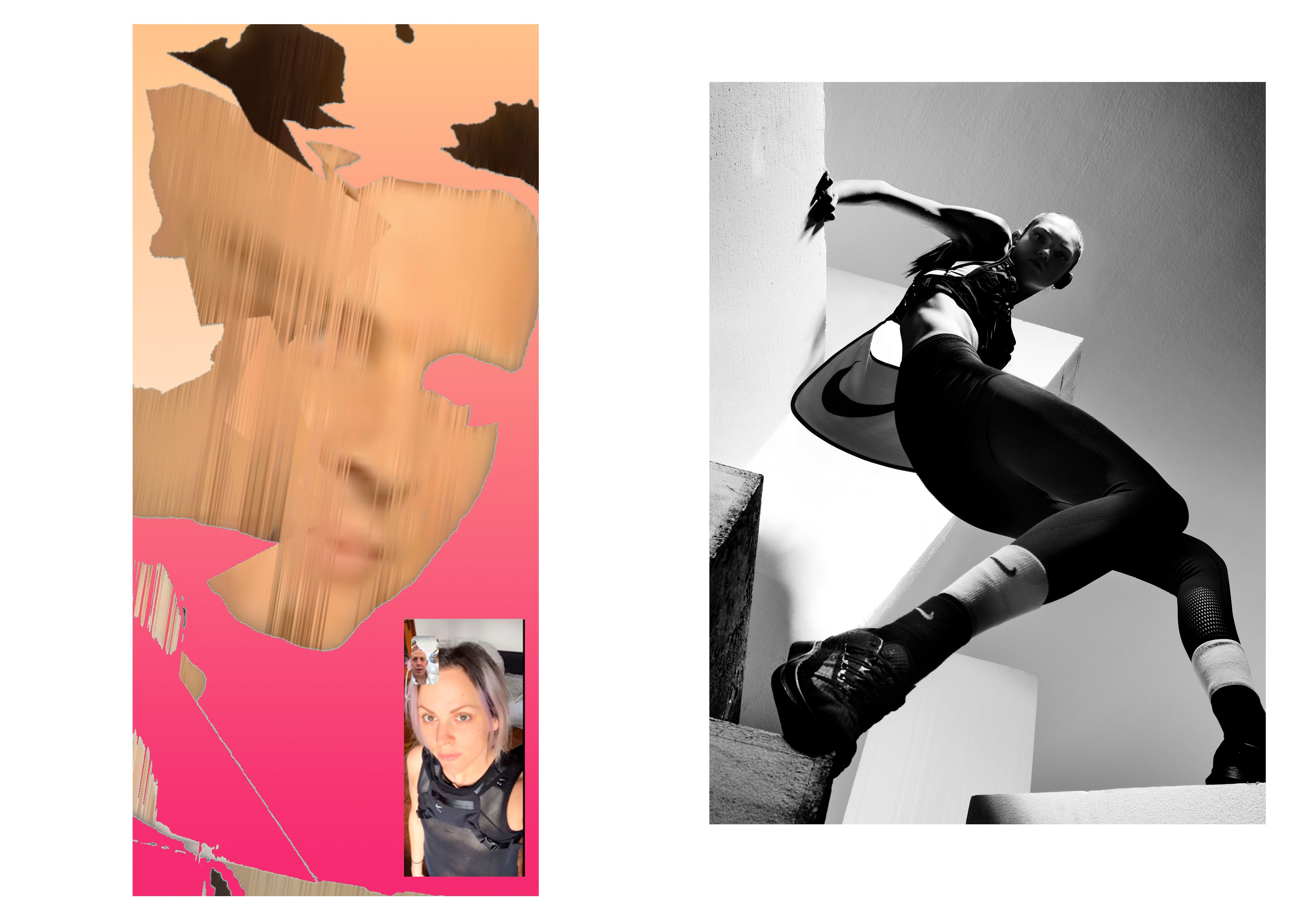

- Imagery: Nick Knight (London)

- Imagery: Britt Lloyd

- Text: Thom Bettridge

- Fashion: Anna Trevelyan

- Art Direction: Everett Vangsnes

- Production: Panottica Srl

- Digital Post-production: Mark Boyle / Epilogue Imaging Limited

- Boxer: Ramla Ali

- Talent: Molly Bair

- Rope Access Technician: Craig Barker

- Fencer: Miles Charley

- Track & Field Athlete: Morgan Lake

- Artist: Lil Miquela

- Ex Royal Marine Commando: Mike Shanti

- Designer: Matthew Williams, Jennifer Williams

- Muse: Valetta Baby x Williams

- Firefighter: Laura Worsley

- Hair: Martin Cullen

- Make-Up: Laura Dominique

- Nails: Kate Cutler

- Casting: Madeleine Ostile / AAMO Casting

- Digital Image Technician: Jo Colley / Passeridae Ltd

- Nike Trainer: Kim Ngo

- Styling Assistants: Ellie May Brown, Cesar Perez, Philip Smith

- Hair Assistants: Linnea Nordberg, Kai Takano

- Make-Up Assistants: Elle McMahon, Naomi Nakamura

- Casting Assistants: Oscar Miles, Lilly Wood

- Photo Assistants: Tom Alexander, Barney Curren, Josie Hall, Myles Hall, Rob Rusling

- Production Assistant: Naomi Martin

- Runners: Georden West, Oscar Zita

- Thanks: Digital Direct

- Artist: Boychild

- Investment Banker / Triathlete: Joe Brown

- Sprinter: Christian Coleman

- Nike and S10 Trainer: Ariel Foxie

- Movement Technician: Joe Holder

- Graphic Designer / Jiu Jitsu: Lindsay James Soto

- Architect / Designer / Basketball athlete: Efe Ramirez

- Producer: Bumble Gnome

- Stylist: Kristtian Chevere

- Make-Up: Yuko Mizuno

- Digital Image Technician: Xavier Marshall

- Photography Assistants: Sean O'Neil, Timothy Shin