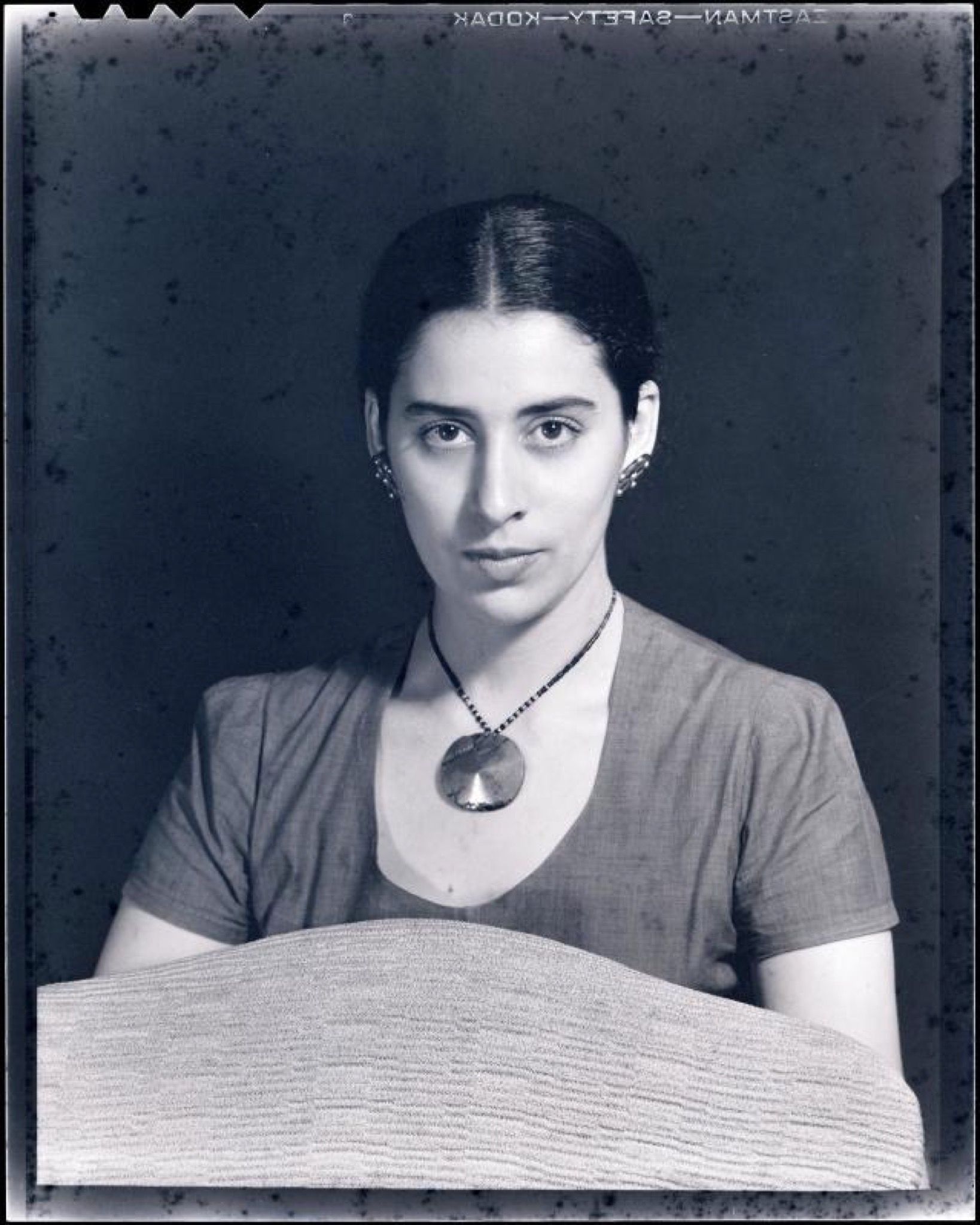

The Last SURREALIST: LUCHITA HURTADO

|Hans Ulrich Obrist

98 years into her life, Luchita Hurtado has been no one and everyone, faceless and famed: muse, butterfly, traveler, wife, designer, feminist, mother, and sorceress. She claims to have been surrounded by art all her life, whether in love, friendship, or solitude. Today, she knows, “It’s the end of the world and nobody wants to listen.”

The Venezuelan-born artist recognizes a tree as her cousin and likes to dream of whales. Her dreams are prophetic, and when the fashion of the time did not suit her, she began making her own clothes. She has birthed three children, two left living. As a little girl, she emigrated to New York City and Orson Welles spoke to her on the street. Later, she counted Peggy Guggenheim, Marcel Duchamp, and Leonora Carrington among her circle. While her friends and lovers in the Surrealist scene were unearthing the totems of lost ancestors, Hurtado was busy making real magic. At the moment, she is in an “orange period.”

You know, I’m 97 years old.

What’s your secret?

I never said “no” to life. Looking back, I sometimes think, “My god, how did I get away with that one?” 97 is a long time. You’re different people.

You have different identities?

Oh, absolutely.

Your story is one of exile. You left Venezuela at a young age to live in New York.

I was eight years old when my mother brought me to New York. Before, I had been living with two maiden aunts, two dear people whose faces I still remember. On the way, we stopped in Puerto Rico, and for the first time I had a green seedless grape. This grape is still very strong in my memory because it was a revelation of what was available in the world. That was magic. New York was a place where I wasn’t understood by anyone. I didn’t know English, of course. The first time I had any inkling was when I heard “elephant.” I concluded that was elefante. That encouraged me, because it wasn’t that different. I lived way uptown in New York, near a place called Inwood Park. I was always interested in art and drawing, and I discovered that the best art school in New York was called Washington Irving, which was an all-girls high school. And so I would make the trip every morning and every evening from an hour away. I remember at that time Orson Welles was my favorite actor. He was performing in Caesar, and I remember going to see it and waiting outside after the performance with a group of girls from Washington Irving. We were waiting to hear that magic voice. When he came out, he spoke to me directly. I thought it was marvelous. It made my life for a week.

Your parents didn’t know that you studied art in New York.

My mother wanted me to study dressmaking. She loved the idea of me being a designer. I loved clothes, and she trusted me, but instead I took art.

How did you come to art?

I was surrounded by art when I grew up. My son Matt Mullican became an artist as well. I remember the first artist I met was Rufino Tamayo. At the time, I was married to my first husband, Daniel del Solar, who was a journalist with the Associated Press. Tamayo moved in with us in New York, where he was teaching at The Dalton School. He would come home and say: “I can’t live this life. When I was teaching today, this little boy came up and said, ‘How do you mix orange?’ I cannot bear that!” He would paint pictures in my kitchen, which was quite extraordinary, and I learned a lot about color.

What did he teach you about color?

Very fundamental things. Put orange here, green there, and something happens. We would play a game where he would ask, for instance, “How would you mix this green?” I was learning without knowing I was learning, because color was a very important part of his work. One day in 1940, my first husband came home with Ailes Gilmour, the half-sister of [Isamu] Noguchi. Ailes and I became very good friends, and so, eventually, I met Noguchi. That was my introduction to the art world, actually, because then, I met everybody.

Did you have any other heroes or influences?

Well, Marcel Duchamp. He was quite wonderful.

You met him?

I was living in Mexico, where I was married to Wolfgang Paalen. When visiting New York, I would stay with Jeanne Reynal on 2nd Street. She had this three-story place where you met everybody who came and went. Duchamp was a close friend of hers, and everybody looked at him with great awe. I remember one night I was going to bed and he arrived unexpectedly. I was in my room in my nightgown, but I couldn’t not go out. So I came out without shoes and sat on a bench. Duchamp came and sat next to me, and he massaged my feet. That made great news.

That was also the moment when the Surrealist scene was arriving in New York City. [Roberto] Matta is there. [André] Breton is there. [Leonora] Carrington is there. Would you say your work in the 1940s was Surrealist?

Well, it came close, not that it had anything to do with anything. I met a great many people. I met Fernand Léger. I met Leonora Carrington and that whole group. I recently found a painting of Leonora’s in my studio. It’s a black cat with a poem written underneath. I remember that when the war started, I would go to meetings at the automat with Jacqueline [Lamba] Breton. The Surrealists held court at the automat, which was very strange.

So the automat was the new Café Deux Magots?

That’s right. And, you know, Breton’s wife, Jacqueline, swam in a tank of water. She was very beautiful. She went from being a performer to being Jacqueline Breton, which was quite a change.

There was also Peggy Guggenheim’s The Art of This Century. Your second husband, Wolfgang Paalen, had an exhibition there.

Peggy Guggenheim wore very heavy earrings, so the lobes of her ears were always hanging. They even came open a little bit. I never had the nerve to tell her, honestly. She had a daughter called Pegeen. I always felt very sorry for Pegeen, because she was a very lonely little girl. I was happy to learn that Pegeen married and had a very simple, wonderful life in Paris. She had children, so that was that.

You were friendly with Friedrich Kiesler at this time as well.

Kiesler was always dressed in black. Even when everyone was in bathing suits, there was Kiesler dressed in black, with a black umbrella over his head. He was a rather large man, too. It was really very strange.

Tell me about how you met Wolfgang Paalen.

Paalen was a marvelous man. He was my teacher. I went to see his show, and he invited me to come to Mexico to see the big Olmec heads that had just been discovered in the middle of La Venta in Chiapas. I was buffing my nails as we flew down to Chiapas, and he said: “You seem to be very brave about flying. You’d make a good student.” I mean, this man was brilliant. He spoke three languages. He published a magazine. We married in a week, and I went back to live with him in his house. And there were these two women, his ex-wife and a masseuse, who were both part of his life. We lived together as a group. It was another life, you see. And I was very young.

Paalen and you were an epicenter in that scene in Mexico. His magazine, DYN, was a very key instrument.

I was immediately given a camera when I married Paalen. We went on these trips – to Chiapas and different places – and I took photographs. He wrote an article on the Chiapas trip called “The Oldest Faces of the New World,” with photographs that I did. I suppose it’s still somewhere.

You took a lot of photographs of shadows.

I was intrigued by shadows for a long time. I don’t remember when, but most of my life I’ve been interested in shadows – their size, what can be done with them.

You and Paalen had collections of masks, of stones – collections of almost everything.

Paalen loved pre-Columbian art. At that time, they were making all these roads in and out of Mexico City, so they would start a road and they would discover burials everywhere. You could see them from the air. You suddenly found these things coming out of the earth, and you’d have necklaces or whatever appearing in Mexico City. I know at that time [Herbert] Joseph Spinden was the head of Brooklyn Museum. He was there collecting. Paalen collected. Everybody collected.

In DYN there was a great deal about the idea of connecting to lost, ancient energies.

The Surrealists called them ancestors. I don’t remember much about it, but it was a very strong element with the Surrealists of that time. There were good ancestors and bad ancestors. I don’t quite remember what that was about.

Leonora Carrington – and Remedios Varo, of course – was part of that scene.

Leonora had these dreams. She’d tell you that she’d left her body and was looking down at herself, and all of these things. I could never do that. Leonora used to take these houses and make wonderful places for children to play, with painted windows. I wonder what happened to those houses, because they were works of art.

For a lot of your life you kept books where you would write down your dreams.

Yes. And it was quite an adventure because I had really, really crazy dreams. Wonderful dreams! And sometimes, you know, foretelling. If you wake up in the middle of the night, you have to write them down.

And you have to put the notebook next to your bed. Because I have observed that when you wake and stand up, you forget your dreams.

Sometimes you miss it. Sometimes the dream is so haunting that you don’t forget. There was a house that came into my dreams, but it was frightening, and I would say: “Don’t go in there. Don’t go in that house.”

Your time in Mexico came to quite a sudden and tragic end with the loss of your son.

He was five years old. He had infantile paralysis and died in a matter of days. Nothing could be done. I called my pediatrician in New York, and they said, “What kind of polio is it?’” And I said, “He has to have help to breathe.” Then silence, and my doctor said: “Just pray that he dies, because he’ll be a basket case. He won’t be able to see or hear, or have any kind of life.” And, indeed, he did die. That’s when I decided I couldn’t live in Mexico anymore.

And that’s how you arrived in California. You came to San Francisco first, right?

Yes, because that’s where Gordon Onslow Ford was, who was a very close friend. That was also the entrance of Lee Mullican, my third husband. The Dynaton Group — Gordon Onslow Ford, Jacqueline Johnson, Lee Mullican. What exactly was that group? Was there a manifesto? Paalen held the group together, actually. I remember Noguchi saying that Onslow Ford had the money, Paalen had the intellect, and Mullican had the talent. I don’t think that’s quite fair, actually. You can’t do that to people. Things change.

And the group had a really big interest in looking at ancient cultural artifacts – from the Pacific Northwest to Eastern religions.

Those were the ancestors. I never took much interest in this ancestor game. It seems to me that it’s all a mystery. They kept saying that physics is a big carpet, and we’re all on it, and that there’s really no Adam and Eve.

Someone who was an important figure for you when you moved to California was Sibyl Moholy-Nagy.

Sibyl was an extraordinary woman. She had a very young lover, and she told him to find someone else because he wanted children and she couldn’t have them. She loved him too much to keep him. Then, of course, he found someone, and they were very happy. But Sibyl was really so unhappy, desperate. I saw her banging her head against a wall. You should never do that. When you’re in love with someone, don’t suggest they leave you. That’s not good.

Then there was Jean Varda. That’s also an important protest against forgetting, to remember Jean Varda.

He was a character, he really was. Everyone admired Varda. He had been a ballet dancer. He met Paalen on the beach. Varda was writing a poem in Greek in the sand, and Paalen was walking down the beach and finished it. That was how they met. I always thought that was a great story. Did you ever meet someone called Edward James?

No.

He was funny, because he wore powder on his cheeks. He had this apartment in Los Angeles, where he would invariably forget to do something. He would call his friends and tell them, “I left the water on,” or something like that. And then you’d have to go to his house and turn the water off. When he wrote poems, he signed them Edward Silence and numbered them. He would make 50 poems and give them to friends as they came. When I lived on Mesa Road in Santa Monica, Edward James came to visit and brought me this wonderful bouquet of white calla lilies. I was delighted and set them down on the table. The next morning, I woke up and went into my garden, and he had cut all my cabbages.

That is extraordinary.

He was an amazing person.

Where does your catalogue raisonné start? When did the student work stop and your work begin?

The very early work I did was a stovetop with lights. It was kind of abstract, but not abstract. I was really interested in fire. And, for me, the first paintings that I remember really being intrigued by and loving were these gas stoves with rings of fire. I think that fire is going to be the way I die.

Are they published in a book?

I have no idea where they are, if they exist. I’ve never been very careful with anything I’ve done. As a matter of fact, all the work I did in Mexico is practically gone. I went to hear Agnes Martin when I was a student. She would crumple pages and throw them on the stage. We became very good friends [in Taos]. We used to have lunch together practically every day.

After the fires, you also painted butterfly figures.

I went back to Venezuela, and in the museum there, they left all the doors open. I was going through the museum, and suddenly this big, beautiful butterfly flew into the museum and landed on the wall.

You have said that you have a very good sense of smell that helps you remember gardens and parks.

I could smell a butterfly breaking through its cocoon, but that was when I was really small. People have asked me what my totemic animal is, and I say that I have two: one is the butterfly, the other is the whale.

Did you paint whales also?

I never did. I dream about whales. Well, I haven’t lately.

Do you have a favorite color?

The thing is that I go through periods. I’m in an orange period at the moment.

So is David Hammons.

Really?

In Mexico, you mostly did oil paintings, but when you came to California, suddenly there was a lot of ink, crayon, and watercolor.

It was so much easier when I discovered this, and my work became all about that.

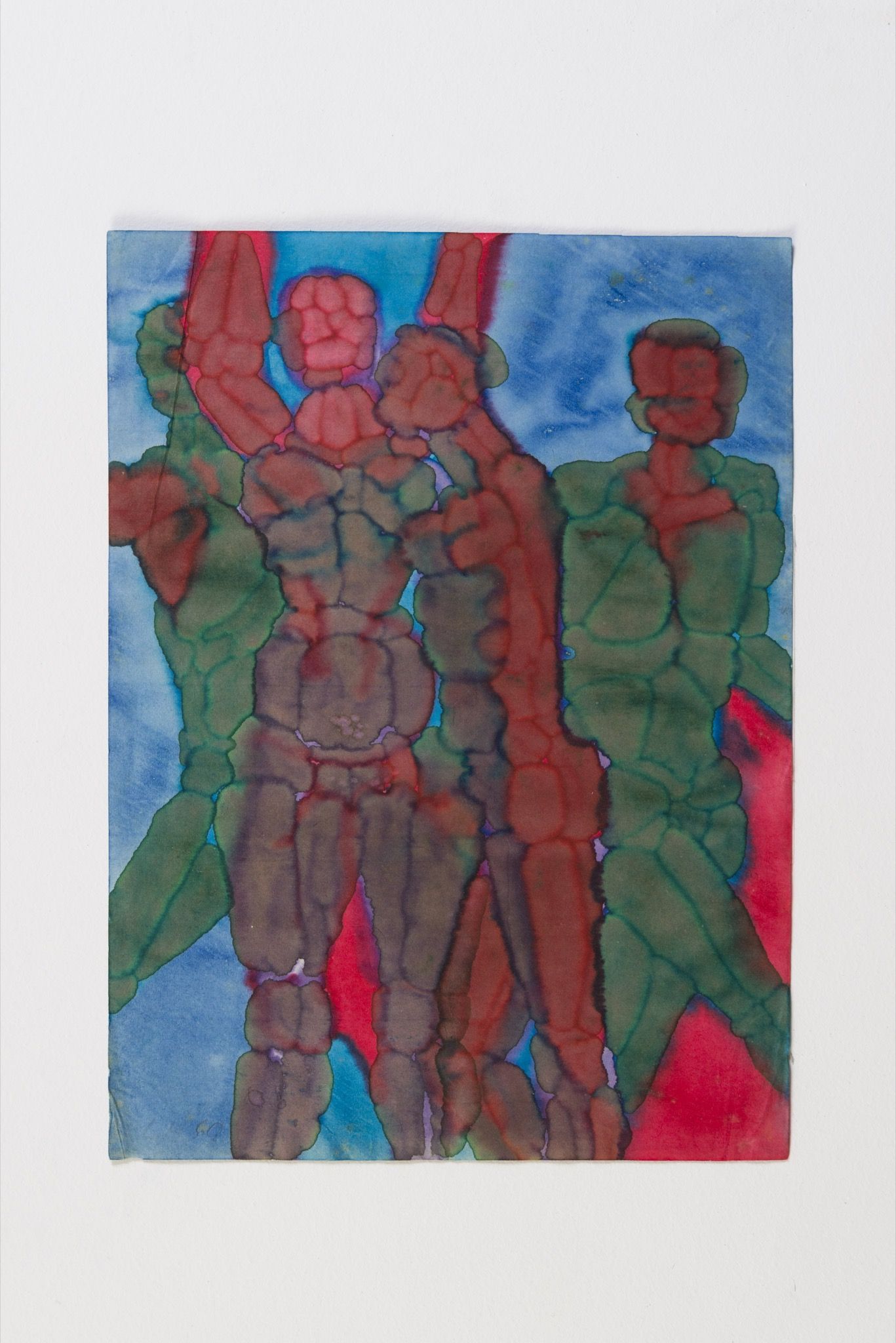

You also have these ink blot pieces.

That was a combination of color and paper. If you have the right colors, they can have little edges that are green. The ink itself can behave differently on different papers. I went through a period of looking at how this happens all on its own. It’s almost like the work has its own life.

Reading about the beginning of your time in Los Angeles, there is a political aspect to your work – in particular, an awareness of ecology – that started then, and remains a part of your work today.

When I saw photographs of the world – the first photographs of the world – where you saw this little planet in the darkness of space, it gave me the same tenderness that you have for family, for your own children. I feel very much that I am part of this planet. That has been very strong in me all my life – that I recognize a tree as my cousin. I have a responsibility here to the world, to my planet. When the Earth first appeared, there were worms. It was worms – not Adam and Eve – that made the Earth, who really fluffed the Earth up so something could grow on it.

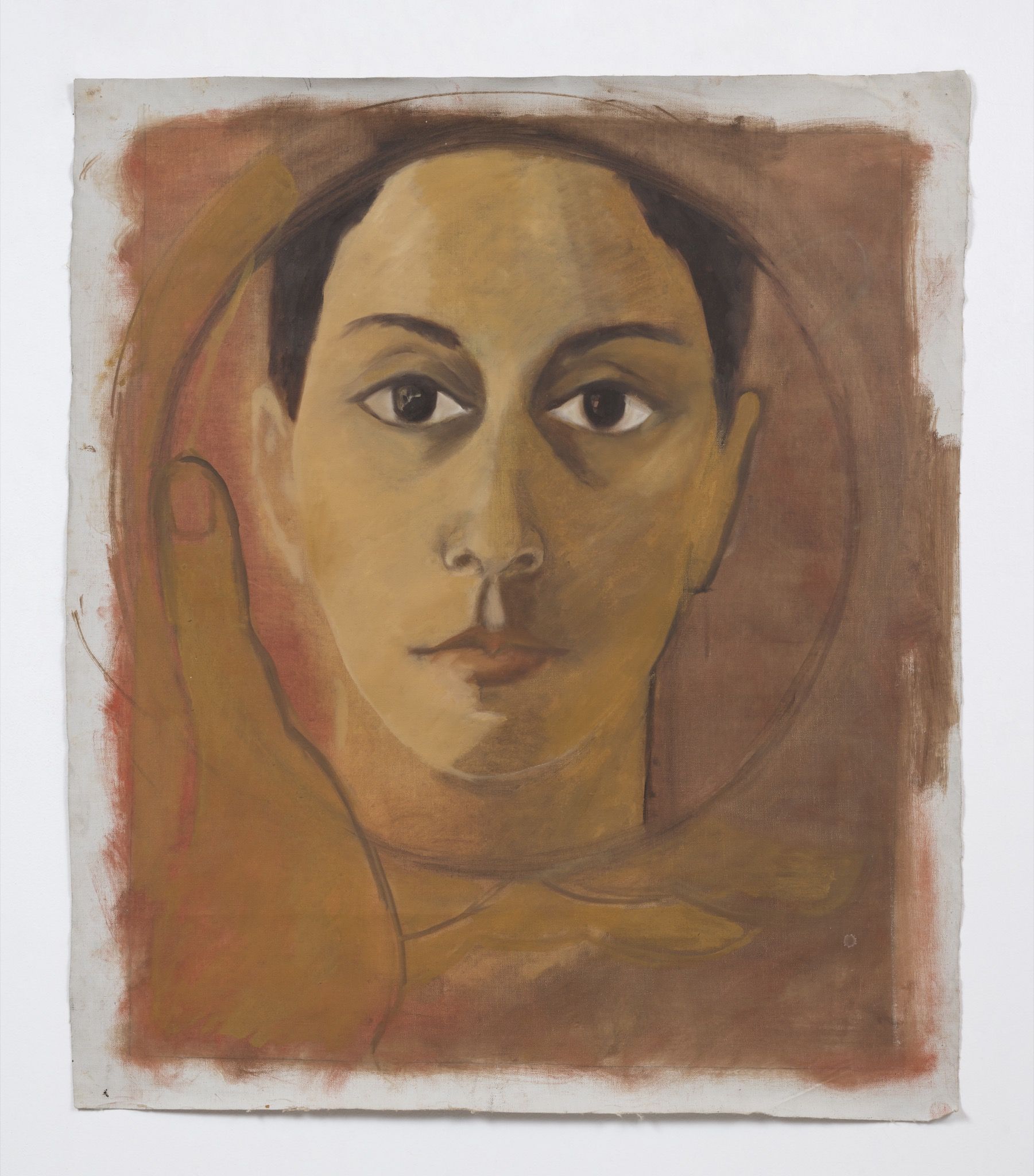

More recently, you’ve done a lot of drawings with words, like you did in the 1970s with these very political paintings, with words like “No,” or “I die,” or “Out,” or “Izm,” or “VS.”

I began to make very fast paintings with very strong lines. I made this special brush to be able to do that. I wanted to paint speed, so there are straight lines and words. The first one I decided to make was a self-portrait. I drew “I am,” and that was my self-portrait. But people don’t know. I don’t think they realize half the time that those are words.

Here in Los Angeles, you were part of a women’s artist group that was organized by Joyce Kozloff, who is a very interesting artist.

That was a very strong group. I remember, I made the mistake of saying my name was Luchita Mullican, because that was the name I was using. But I was Luchita Hurtado. It became very strong in my life to remember that name. And then, when they discovered it, I lived again.

Can you tell me more about these groups, because Nancy Spero and Louise Bourgeois have told me about the activities of collective groups of women artists in New York City, but I know less about this here on the West Coast.

It had to do with where you lived and who you knew. My group was Vija Celmins, Alexis Smith, me, and Avilda Moses, and there were others, but at the moment, I don’t remember. I have all the information I want in my head, but I have to think about it for it to appear. It could happen tomorrow, or it could happen any time.

Even though you didn’t exhibit for all these years, there was never an interruption. You always made art.

I never stopped, did I? I couldn’t help myself. When I had children, I would work at night. We had a house in Mill Valley that I think was haunted, because I would work at night and suddenly the room would fill up with the smell of mimosa. Very strong. And I would get up and say: “Show yourself! You’re here! Show yourself! Drop something!” But nothing ever happened.

I remember reading your description of that house. It sounds terrifying.

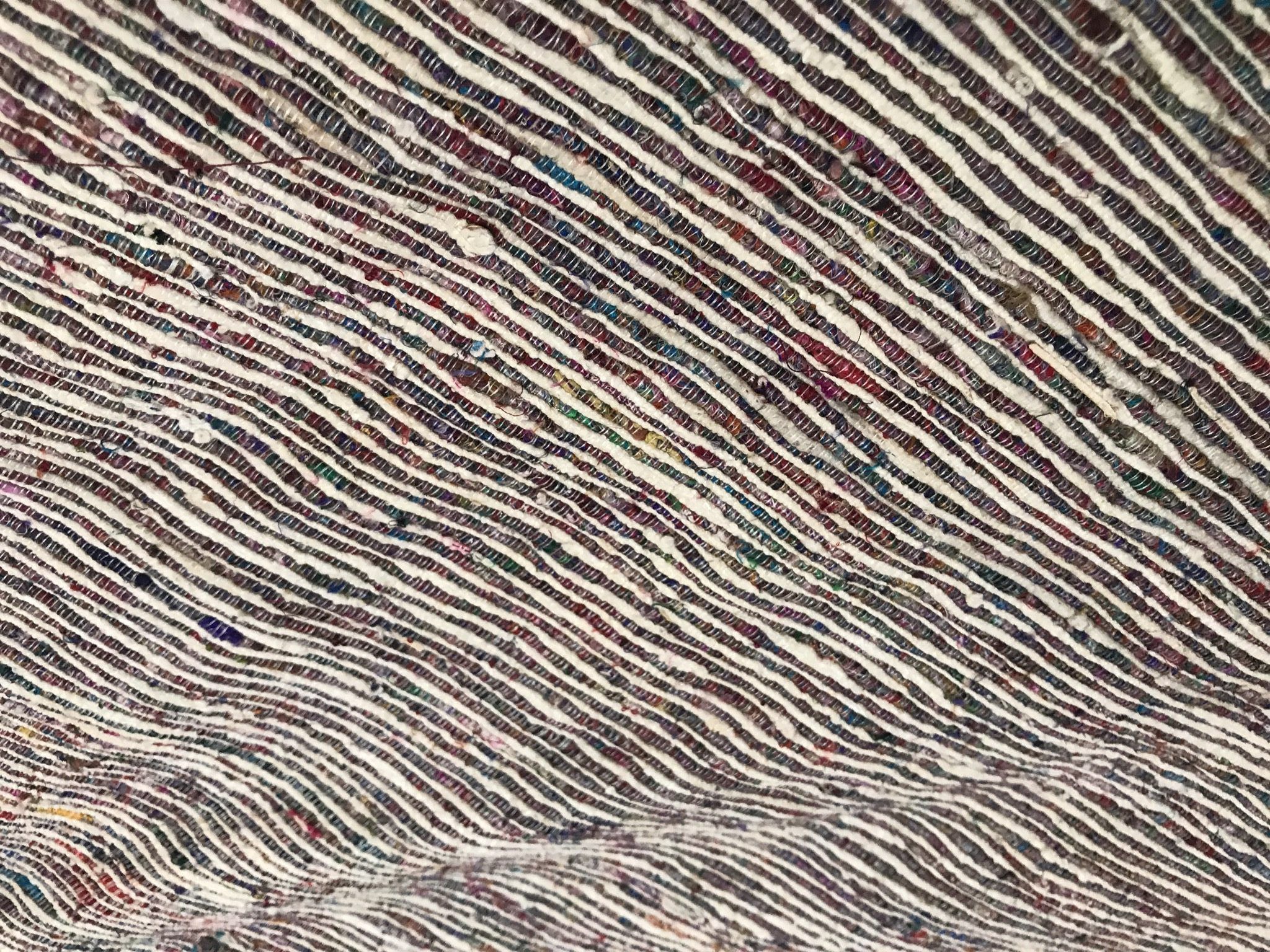

It was a weird house. But I would work at night when I could. There were times when I was unhappy with a painting, and I would cut the canvas up into strips. I make my own clothes, so I have a sewing machine. And I would sew the paintings together. I was very happy with it in the end. Some of them were eight feet tall, ten feet tall. As big as I could handle.

You have an entire archive in your studio of your own clothes, which you designed and made, like the amazing outfit you’re wearing today. How did that practice start?

I’ve always loved clothes. I remember it started with textures. I love textures. I love color. When I was pregnant with my first child, I was 20 years old, and they had these “butcher boy” shirts. They were awful-looking things that had a hole in the front where your belly hung out. It was just ugly. So I decided to make my own clothes.

That was the beginning.

Yes. I had a vision of a very low décolleté striped in black and white, with tiny puff sleeves. I put the sleeves in the wrong way! But I wore it just the same and enjoyed it. I like to make crazy nightgowns. I used to have big projects, like coats and raincoats. Stuff like that. But now, it’s just a shirt now and then, not much.

“Duchamp came and sat next to me, and he massaged my feet.”

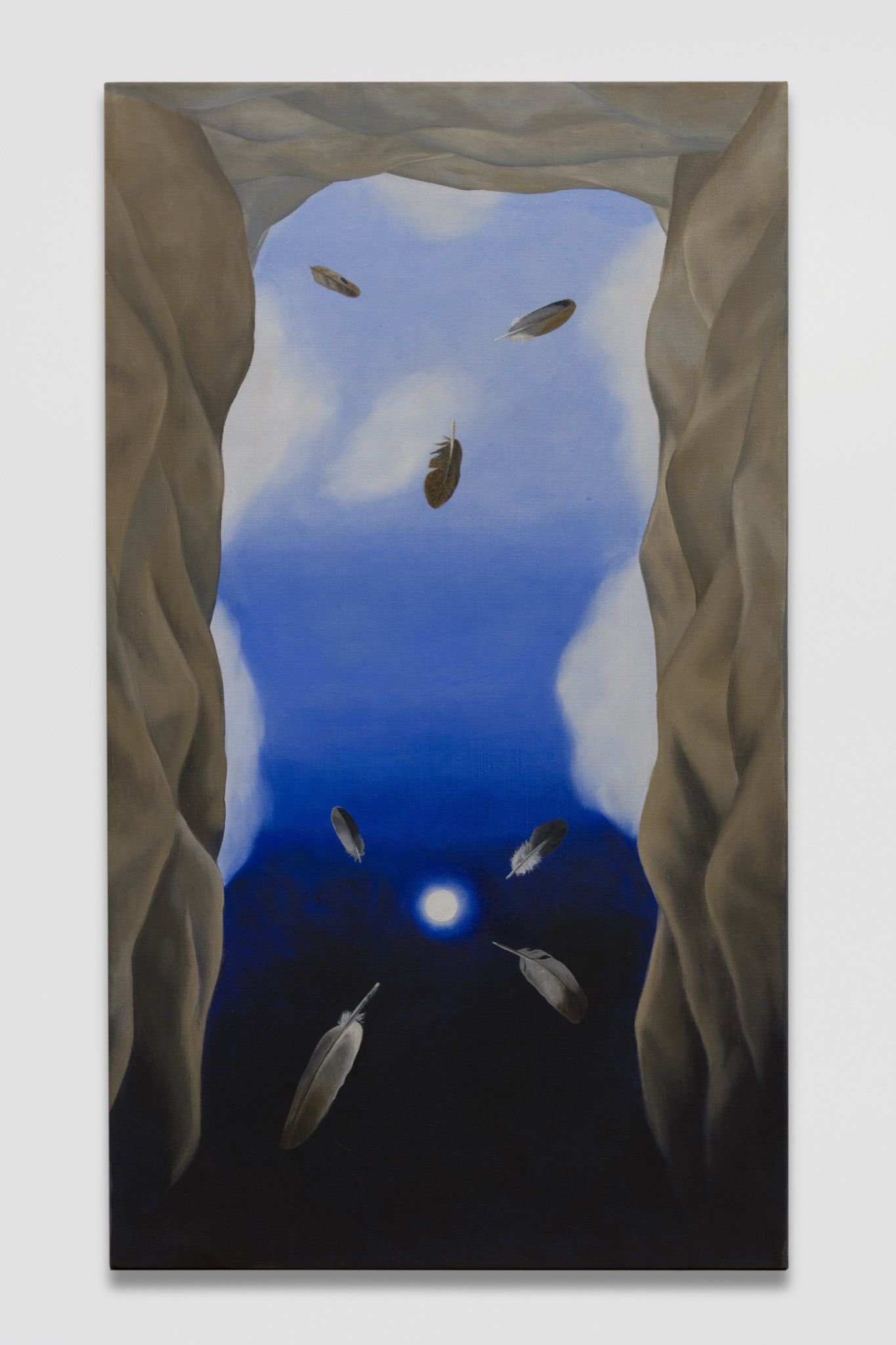

Can you tell us a little bit about what’s going on in your studio in 2018?

Well, it’s air, water, fire, earth – the elements. That’s what’s there in my studio. That’s what I’m working on.

Are you using the Internet at all?

No, no.

No iPhone?

I feel that it would take up too much of my time. And I’m really not interested in Facebook, or whatever it’s called. I think it’s more important that you are where you are.

So you don’t live in the past?

No, nor in the future. I’m very involved in what’s happening in the world today. It’s the end of the world and nobody wants to listen. I used to go out and hold placards all the time, but I’m too old to do that anymore. This day and age is so strange to me. I still wonder at that first photograph of the Earth. What we’re living now used to be science fiction.

I’m always interested in unrealized projects. We know a lot about architects’ unrealized projects because they publish them all the time, but we know very little about artists’ unrealized projects. For example, I once asked Louise Bourgeois – one of the most published artists, with hundreds of books – what her unrealized project was. Nobody knew she wanted to build a little amphitheater for tiny performances. That sadly remained unrealized. I wanted to ask if you could tell us about your unrealized projects – dreams, things that have been too big to be realized, or too small to be realized, or forgotten.

I always wanted to paint light. It’s hard to do.

Rainer Maria Rilke wrote this little book, which is so amazing, called Letters to a Young Poet. What, in 2018, would be your advice to a young artist?

Find it. Look and find it. Because it’s there.

Credits

- Text: Hans Ulrich Obrist

- Photography: Max Farago