THE SPECTRE OF MIES OVER LONDON: JACK SELF Interviews LORD PETER PALUMBO

|Jack Self

The great modernist architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe only ever designed one project for Britain, and yet it remains one of his least known – both because it was never built, and because for more than thirty years the drawings were kept private by the commissioning developer, Lord Peter Palumbo. Now London’s REAL foundation, who curated the British Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale last year, have gained unprecedented access and are using Kickstarter to produce the first ever book on the project. In a rare public interview, REAL director and 032c Editor-at-Large Jack Self spoke to Lord Palumbo in his private member’s club, the Walbrook, an 18th century ex-vicar’s house practically opposite the Bank of England.

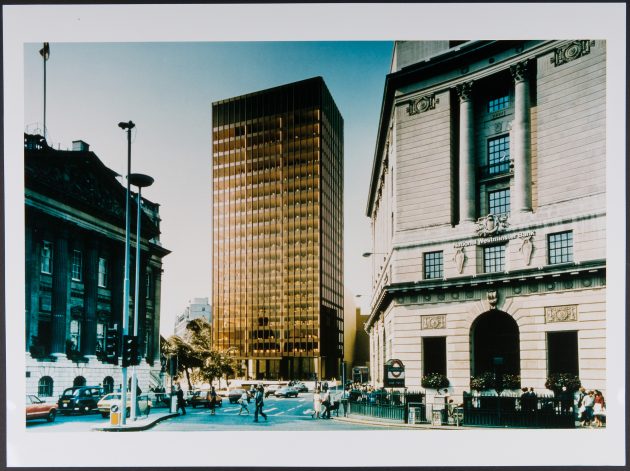

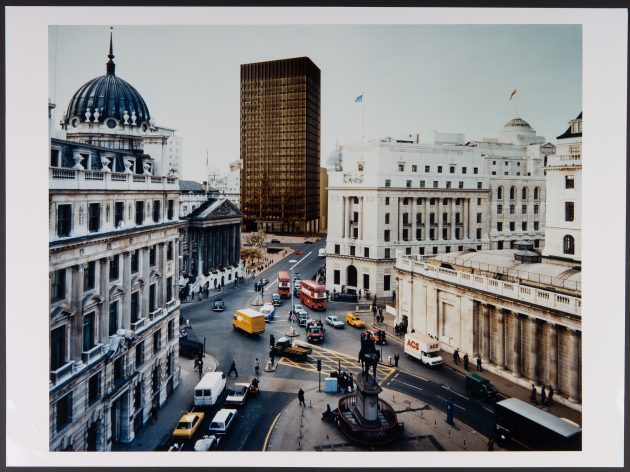

JACK SELF: Mies’s design was for a mid-rise office tower and civic square to be sited in the City of London, adjacent to the Lord Mayor’s Mansion House. After a string of public inquiries – and suffering vicious criticism from the Prince of Wales – the scheme was eventually halted by government order in May 1985, more than two decades after design work began. Its architect was belittled as a communist and a German. The project was perceived as “past its time and neglectful of its place.” And in a strange way, Mansion House Square became the focus for a sudden and radical shift in popular opinion against modernist architecture. But I want to begin at the beginning if I can – how and why did you come to be involved with Mies van der Rohe?

LORD PETER PALUMBO: Originally there was no intention to create a large development. The gradual acquisition of sites near Mansion House was purely for investment. My father had some spare cash, about a hundred thousand pounds, and he asked me what I thought to do with it. We bought one site, and then the freehold became available on an adjacent property. In the 1960s it was actually quite difficult – and sometimes almost impossible – to acquire freehold titles, the owners were so reluctant to part with them. As more freeholds in the area sprung up, the possibility of a major development began to take shape. I remember my father and I both realising that it was a very prominent site. I knew it could be an exciting project, but because of how sensitive the site was I knew planning would not be easy and there would be lots of opposition.

As to how I selected the architect: Mies was Northern European. He liked grey skies. This made him a man ideally suited to London. He liked the weather patterns here and he didn’t like bright sunlight in particular; he was very sensitive to light conditions. The essence of the project, in my mind at that time, was all about light and classical architecture. So the choice really made itself, it was as simple as that. Of course, I made up my mind unbeknownst to Mies at the time.

How did you get in touch with him?

I wrote to him, and I got a reply saying just, “Come see me.” So I did, and there he was. It was early July in 1962 that I first went to Chicago. I remember it was boiling hot and I was rather nervous. But he wasn’t at all condescending, which I liked very much. It’s nice when older people aren’t patronizing toward younger men. And of course I knew a lot of his work, and his early work, so I think he quite liked that.

We got on well, and I asked him if he would be interested in the commission. I told him that there was one condition that couldn’t be circumvented: because of the complexity of purchasing the site – which was enormous actually, twelve freeholds and about two-hundred and fifty leasehold interests, each one of which had to be separately dealt with – it was unlikely that any building would take place within the next twenty-five years. He was seventy-five at the time and he understood at once that what I was offering him was a posthumous commission. He was a bit noncommittal, and eventually asked, “Well, what do you want? A sketch on the back of an envelope, or what?”

I replied, “I want the whole kit and caboodle. I want everything: the mullions, the door handles, the ashtrays. I would like you to prepare detailed plans, engineering, materials, even letter-chutes.”

He never formally accepted the commission but several months later I got a colossal package from America that weighed an enormous amount. When I unwrapped it I found a package of drawings, a section of bronze mullion, a stone ashtray and a door handle with a note in his writing that said, “Is this what you had in mind?”

Did you know much about what kind of building could be built?

We knew the number of square feet, which was taken from the existing Victorian buildings and transferred directly into the tower to make it, I believe, one hundred and ninety-two feet and six inches − lest we forget the six inches! We had also done a very good survey of what lay underneath the ground level. It had been a major thoroughfare for several thousand years, at least since Roman times, when it was called the Via Decumana. This street ran right through the site all the way to the Roman forum (the ruins of which can be seen today under Leadenhall Market). There were all sorts of things under the ground that made the engineering very complicated. We knew about, and had documented, the pitfalls of the site, which Mies didn’t like at all. After at least a dozen studies of alternative positions for the building he settled on a tower.

Was Mies keen to build in London?

Yes. Although, he didn’t accept the commission before he was able to visit the site. On his way back from Berlin and the National Gallery to Chicago he stopped over. It was rather wonderful actually, because there was a huge swell of momentum. The Evening Standard – in its glory days – ran the banner headline “Mies Comes to London” on the front page.

Can you imagine an architect triggering that type of news today?

No, not all. He came to London and we booked him to stay at Claridge’s Hotel. I borrowed some paintings to decorate the room – he loved Kurt Schwitters, so I got two from the Marlborough Gallery and put them in his suite, to make him feel at home.

I just can’t imagine a developer today ever having such consideration for an architect. Did you have a tenant lined up before the final design work began?

Yes, we had a tenant who wanted the whole building, lock, stock and barrel. As a family we had been banking with Lloyd’s Bank since 1924; my father was very close to them, and I became very close to them as a result. When we discussed the project they said they would take it for their Overseas Head Office. After waiting for 12 years, in the end they couldn’t wait any longer and had to drop their interest.

During the visit, the Chancellor of Lloyd’s wanted to give a lunch for Mies. Can you imagine that? So Mies was brought round in his wheelchair to the front entrance on Lombard Street. All the directors had been marshalled into two lines that Mies was wheeled through, rather like a marriage or a military decoration. It was absolutely extraordinary. I think Mies was rather unnerved by the whole thing; he wasn’t that sort of person at all. But the Chairman, the Vice President and the entire Board of Directors were all there. It was like a royal procession, in a way. And so Mies was given, by the LLC, by the City Corporation and by Lloyd’s Bank, every kind of consideration you could imagine.

Later he said, “Well, that was all very nice but actions speak louder than words. Let’s get on with this.”

Mies didn’t like hanging about; he didn’t like all that ceremony. He wanted to get the building built. Unfortunately, we couldn’t do that though – because we didn’t have complete control of the site (I think we only had forty percent at that time). But we did get a planning permission outline from the City Corporation, which meant that as soon as we had full control of the site it was plausible enough that the building could be built.

Yes, in those days it was possible to file permissions for land you didn’t own – a process eventually stopped after Cedric Price applied to change the zoning of Buckingham Palace to a children’s hospital.

We filed on land we didn’t own, that’s exactly what we did. And as soon as we got the sites, they implied they would give us full planning consent.

How long was the project under design?

It was under design for a long time. It began in 1963 and only ended a few weeks before Mies’ death in 1969. On his second visit to London he wasn’t happy with the module from the first design. I remember wheeling him up and down Poultry and he said, “This scheme won’t do, because it doesn’t harmonise with the Lutyens building,” which was on the north side of Poultry. So he changed the module, made the canopy and proportions align with those of Lutyens, and that was the final design.

How did the square evolve? There’s a prevalent myth that the square was criticised for being a potential site of protest, but this was not at all how it was conceived or perceived at the time.

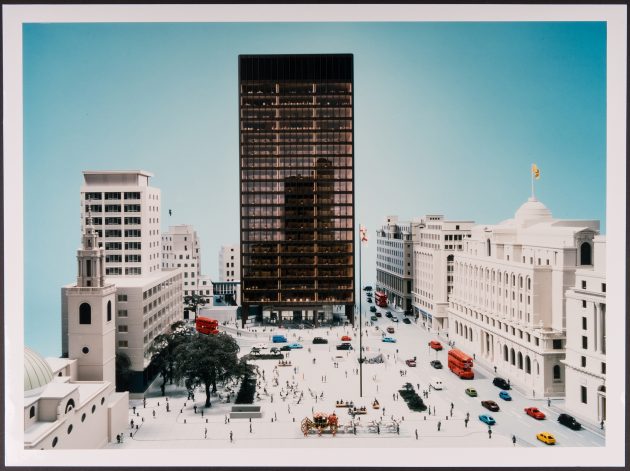

No, not at all, on the contrary. It was initially created out of pure necessity. The shallow depth of the underground rail tunnels made deep foundations extremely difficult except at the western end of the site. If a tower was to be planned all the floor area would go into that, which necessitated a square. But it was the historian John Summerson who understood this square for all its civic possibilities. We had lunch in Soho once and he spoke about Mies’ scheme. He said, “I like this building. I like it because it’s so classical. There’s a lot of rubbish on the site at present. Let’s photograph it in detail and take it all down, and put this up because it’s much, much better.” As he was leaving, he said, “I think I’ll write a letter to The Times to kick things off,” which he did. The letter was about the evolution of the city, and how Mies’ building would be a much better solution for the site. He argued the scheme with the square would provide much needed respite at a congested junction – where nobody had anywhere to sit, or anywhere to walk without danger of being run over. The ceremonial possibilities of Mansion House were quite limited, and he wanted to open that up. That letter set the tone for the square’s public perception as a gathering place.

This conception of the square as a ceremonial place presumably explains the later addition of huge flagpoles with English flags?

Yes! The flagpole took a long time to position. The very last thing Mies did on the project was to position the flagpole. It was narrowed down to two or three different positions and finally Mies decided on the precise location. He signed the drawings and died a couple of weeks later. But the project was executed to that amount of detail.

And you know, looking back I think the square would have been a wonderful spot for protests, but it wasn’t imagined for that. It was a ceremonial opening up of the land – clearing away congestion and creating a gathering place for the people (for civic and therapeutic reasons, not for political protests).

It would have been a site for public ritual in the city.

Yes, of course. Mies saw that. It sort of all fell into place with his positioning of the building, the ceremonial aspect of the square. Everything was opened up: the façade of Mansion House – though it’s not a particularly magnificent façade, but it has a symbolic function for the Mayor of London – and the views beyond to the Royal Exchange. There’s also the Edwin Lutyens building on the north side and John Soane’s Bank of England adjacent. And of course there is St. Stephen’s church by Christopher Wren on the other corner. It’s a pretty good list.

Why wasn’t the project built?

It didn’t happen for the very simple reason that between when we got the planning permission outline and Mies’s death, public sentiment had changed. In the 1960s you could do whatever you liked, but by the 1980s there was a hangover from the postwar euphoria. There was a very definite philosophical shift, and a popular idea that tradition had been lost. Mies was central to all this, in a way, with this building in the center of London. It was symbolic of public feeling at the time. Within twelve years of Mies’s death, there was a complete shift. Suddenly everything had to be preserved and conserved. Old buildings had to be repaired or reconstructed. It was extraordinary. I always thought that this shift was such a mistake. The pendulum never centers, as John Summerson once said to me. He felt we should only keep what is wonderful, but get rid of the cheap buildings thrown up in the 1870s with bad foundations, where none of the floors and windows lined up. Just because a building is old doesn’t mean it has merit. On our site these Victorian piles were built quickly as pure speculation, and had little historical value.

By 1982, the LCC began to move the goalposts very rapidly. They denigrated Mies, saying that he was German, that he was a communist, that he was foreign. Then they said it was just a formulaic building; that Mies really had nothing to do with it at all.

Of course, it seems somewhat contradictory to denigrate and ridicule the architect while simultaneously disavowing his connection with the building itself.

Well presumably, one would affect the other. In the 1960s, “Mies Comes to London” was the banner headline. By the eighties, people were asking, “Who the hell was he?” It shows how quickly people forget, or want to forget, to propagate their own plans.

In the end Lloyd’s Bank got fed up and said they couldn’t wait any longer, so they dropped out. We were left with a site that was losing money and we were still trying to acquire freehold titles. We got stuck. I mean, we couldn’t afford to go back and we couldn’t seem to move forward. We were sandwiched.

And then, right at that moment, the Prince of Wales gave his carbuncle speech.

When Charles Correa was awarded the RIBA Gold Medal at Hampton Court in 1984, the Prince of Wales gave a lengthy, public and derogatory dispraise of the building. He picked out the tower as “a giant glass stump.” It was a horrible thing to say. And from that moment onwards the project sort of slipped away from us, because we were in the middle of a public inquiry and Charles’s comments just made things ten times worse. Of course, the opposition took full advantage of that.

Do you think Charles realised how much weight his opinion would carry?

Yes, I’m sure he did. When we had the dinner after the Gold Medal ceremony the Prince was at the next table. I asked him about the whole thing, and I said, “I had no idea you felt this way. Why didn’t we talk about this before?” And he said, “I just thought I would stir things up a bit!” I could hardly find words. I knew him quite well, we played polo together – we were on the same team!

I’ll never forget though, right after the ceremony every eye in the place was focussed on me, waiting for my reaction. Then Charles [Correa] and Richard [Rogers], starting from the other side of the room, crossed very slowly and deliberately over to me. In full view they put their hands on my arm and said, “Not to worry, this will all blow over.” They wanted to be seen to be supporting me.

Do you think the Prince’s comment expressed a genuine concern for the fabric of London?

Oh, I’m sure he was completely sincere. He doesn’t like most contemporary buildings but the point is that it was not contemporary. I mean, it was contemporary in the sense that it was being built at the time, but for anybody who has any knowledge of Schinkel and the classical roots of Mies, it wasn’t. Mies really hated machine-architects and the glorification of the machine age. This was a hand-made building. It wasn’t the sort of thing that was just put up after ten minutes.

Mies put so much thought into every detail. If you asked him a question there would be silence, and he would stand there, and you would wait for the reply, and wait, and eventually you would stop talking; the conversation would end. And when the conversation was completely dead, he would come in with his reflection.

At what point did you know the project was doomed? Was it at the end of the inquiry? Or when Prince Charles made his statement?

No, we gave up the ghost of Mies when we heard the Secretary of State’s decision. He said the building was bad mannered, that it was out of context, and it impinged on the conservation area. The listed buildings to be demolished were of some importance and… well, et cetera, et cetera. He even mentioned that the view from the nineteenth tee at Sydenham Golf Club would not have been a satisfactory image − I mean come on! It’s unbelievable. He said, “But, if the developer,” and I think he said it because he was a friend of mine, “can come back with a scheme that is more in sympathy with the surroundings, we would be pleased to look at it.” So that was the lifeline that led to James Stirling’s project.

Despite the bitter loss of Mies, were you happy with Stirling’s building in the end?

Well, it wasn’t my first love. You know there’s something very important about your first love, you never quite get over it. Jim was very sympathetic to Mies because Mies had been very good to him when he first went to Chicago and didn’t get any real attention. Mies took Jim under his wing and Jim never forgot it, the old paratrooper. He was a wonderful man too. God, he was terrific.

I remember the last time I saw Mies, he said, “I’ve done everything that I could possibly do for this site. If you came to me in fifty years time – if we would both be alive – I might have a completely different solution, but this is as far as technology allows me to go at the moment and I’ve done the best for you that I can.” It was a rather nice final meeting we had. He just placed the flagpole and said, “There. I can’t do any more.”

Credits

- Interview: Jack Self