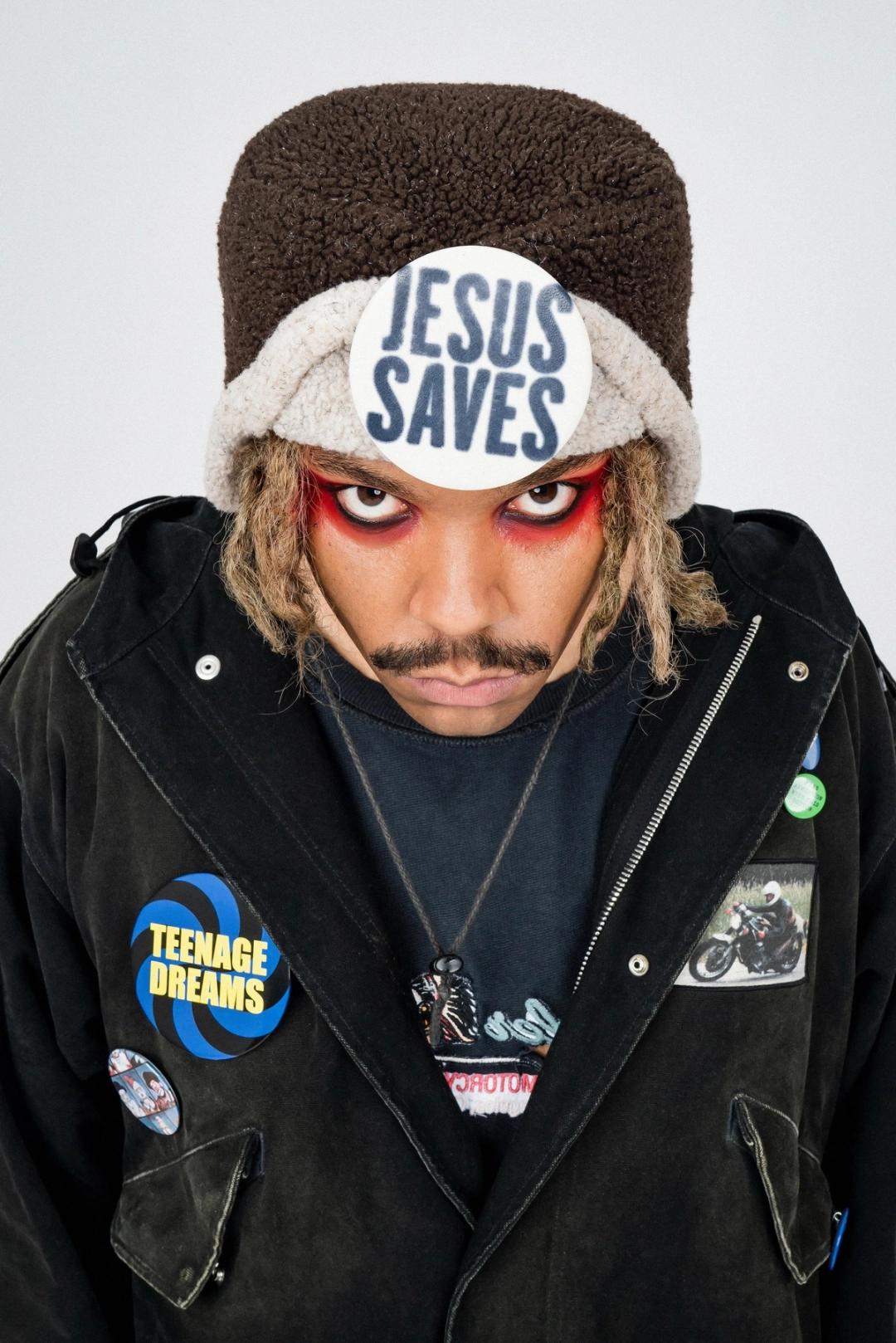

JEAN DAWSON: Chaotic Good*

|Cassidy George

In the repertoire of cinematic devices used to elicit emotion, the montage is the final boss. Montages are if not the most climatic, then at least among the most memorable scenes in cult classics like The Godfather, Trainspotting, Donnie Darko, American Beauty, Apocalypse Now and The Breakfast Club. In these euphoric crescendos – the score is just as crucial as the imagery in depicting evolution, devolution or transformation. Listening to Jean Dawson’s music elicits a similar kind of dopamine rush. Each of his songs sounds like the soundtrack to a montage that doesn’t yet exist. His songs are a template that listeners fill with the flashing images of their memories from the past, or dreams of a future not yet lived.

As a musician, filmmaker and visual artist who is both Black and Chicano, Dawson is a montage incarnate. With his home in Mexico and his school in California, Dawson grew up constantly moving between worlds and occupying spaces of tension, and vividly recounts a childhood that was shaped by the border. On the weekends, he escaped into film – and owes much of his education and interest in moviemaking to his ritualistic trips to Blockbuster. The anarcho-surrealist visual identity and patchwork sound he’s known for today were equally shaped by yet another defunct millennial media entity: Tumblr. Dawson’s breadth of references include everything from J-Kwon’s “Tipsy” to Peter Kropotkin’s The Conquest of Bread, and hosts these unlikely amalgamations as seamlessly as a blog. In accordance with yet another tool beloved by filmmakers – Gestalt theory – in Dawson and everything he creates, the meaning of the whole is different than the sum of its parts.

Last month, Dawson released his sophomore album, CHAOS NOW*. It is an expectantly cinematic record that reaffirms a pattern in his work, shaped by a recurring commitment to putting people, places and things into contexts in which they don’t traditionally “belong.” Sonically and visually, Dawson inserts aspects of his own experience into the tropes and aesthetics of white, rock subcultures – and welcomes fans into the overlapping space in a Venn diagram of outsider perspectives. Each track on CHAOS NOW* is a fractal of this kind of fusion. “I want it to be like if Morrissey was Black,” he once told DIY of his music, before laughing and adding: “I think Morrissey would really hate that!” Dawson has yet to receive a sign-off from The Smith’s lead singer, but he has already bewitched an impressive list of superstar admirers. He has collaborated with A$AP Rocky, Earl Sweatshirt, Mac DeMarco and SZA – who tweeted “JEAN DAWSON IS THE FUTURE” after spending time with him in the studio.

During our call Dawson emphasized that his artistic practice is “about combatting invisibility.” In learning about his father’s participation in lowriding culture – which he makes an homage to in the music video for “PIRATE RADIO*” – it occurred to me that Dawson carries the creative urge to make the unseen seen in his blood. The low-suspended cars with head-turning exteriors and hydraulics that have colored the highways of the American West since the post-war period are declarations of Chicano pride. Dawson, who also makes moving statements, is customizing a new model of celebration. “I want to make sure everyone has a frame,” he said. Over the course of our long conversation, Dawson chauffeured me through the complex terrain of CHAOS NOW* with grace and ease. Given it’s typically my job to navigate, it was both a luxury and a privilege to be able to simply buckle up and enjoy the ride.

CG: You crossed the Mexican-American border twice every day on your way to and from school as a kid. I would imagine crossing a threshold that is so weighted with political and symbolic meaning sparked a lot of reflection.

JD: It did. I was way too introspective, way too young – for the betterment of my creative life, but to the detriment of my mental health. As a kid, I had the responsibility of getting myself to and from school, which happened to be four hours away from my home. I got up at four in the morning, took a bus and then waited in the borderline for an hour and a half. After crossing, I took another bus to the trolley and rode that for 45 minutes. Then I got to school. All I could do was stare out the window and listen to music that I had on a JVC player with CDs I stole from the library. The amount of time I spent lost in thought allowed me to create a new reality within my head.

I was really, really tired at school. Imagine showing up everyday and feeling like you just got off a flight! But I was fortunate to have that migratory experience because I was able to see the real disparity of the world, really young, really quickly. Every day, I saw Mexican kids my same age juggling sandbags and fire at the border. I remember asking my brother why they didn’t go to school and he just said “because they can’t.” So in my head, I went to school for them too.

CG: Does the rage in your music stem from being so submerged in those disparities from such a young age?

JD: People ask me why I put asterisks behind all of my song titles. It’s because I grew up tossing fireworks in Mexico. Fireworks are aggressive but they make you smile at the end. My songs are similar.

I have built up a lot of emotive life experience that came from crossing the border but also from growing up without a dad and with a mom who I saw for maybe 20 minutes a day. That was no fault of her own by the way, she just worked multiple jobs. That absence gave me a lot of freedom, so much freedom that by the time I was 19, I was burned out on doing dangerous shit and being bad. Since then I haven’t had one sip of alcohol or done any drugs because I feel the life I lived before supplements my current reality.

Now, I’m raw dogging life in every conceivable way. I’m keenly aware of the things that trigger my emotions and I feel these extremes, but I don’t have anything to filter that. Many of the realities of the world make me very, very angry. But I refuse to let all of the bad in the world decimate my innocence or erode my faith in other people. I could have taken my aggression out on the world in a negative way, but I chose a different outlet. An angry person can scream and yell all they want. Someone who knows how to channel that into something more profound or thought-provoking transforms that negative emotion into power. Frustration becomes catharsis.

I can’t pretend to be a hero, but what I can do is focus on the message of the music. There’s a song on that album called “ZERO HEROES*” and the chant line is “Oh I know I can.” When I perform that and get to see hundreds of kids singing “Oh I know I can in my face” back at me, that’s my therapy.

CG: Horror is a big subject in your discography. Monsters, demons and freaks are recurring tropes. You also describe yourself as these things in your lyrics. Why?

JD: The darker imagery is a parallel representation of our reality. I’m not trying to say that everything is fucked because I’m not a fatalist in that way. I’m the opposite – I see beauty and meaning in everything. There are many real monsters in the world, but monsters are often misunderstood. Sometimes they are only monsters because the world believes them to be monsters.

I call myself Cerberus, the three-headed dog that guards the underworld – which is what the song “THREE HEADS*” is about. Each “head” is a fractalized version of my personality. I am constantly trying to figure out which head controls what aspect of my life, art, ambition and behavior.

I know this sounds crazy, but I think one of the most helpful and challenging exercises you can do is just stare at yourself in the mirror for 20 minutes. Ask yourself: “Who are you, really?” I’m a brother. I’m misunderstood. I’m sometimes ego-driven. I am all of these things at the same time. I have tattoos of screws on my neck because I’m Frankenstein’s monster – a monster of my own experience.

CG: The word that comes to mind is simultaneity, which is certainly true of your identity. I think the dog has more than three heads, actually! We are made to believe that in order to feel a sense of belonging within a particular community or to become a certain noun, we have to either ignore or denounce the other parts of ourselves – which is bullshit. Your music is a reminder that simultaneity is a reality for all of us. Is the idea that it’s okay to be chaotic?

JD: I think the most beautiful thing in the world is naivete, and that’s how I approach my work. People constantly ask me: “What genre is this?” When I’m making something, I’m like, “What about this? And this! And this!” It’s like when a little kid is telling you about their day. They don’t know how to use commas and speak in a string of thoughts. “I went outside and then I was with the dog and then I had a popsicle and then and then…” For me, beauty lingers right in that spot – or rather in that line. Sometimes following it lands you in dark places. Other times, you begin in dark places and then find your way out.

My biggest objective, and really the only one that matters, is telling people that it’s okay to be who they are. I’m not talking about individualism, as in the way you dress or who you hang out with. I’m talking about the thoughts that you have when you’re alone – the negative things you say to yourself and no one else. That self-talk is programmed to destroy you. Getting rid of it takes a lot of work, but it doesn’t have to be a part of your life. Why do we hold on to this exclusive right to be so cruel to ourselves? Or to anybody else for that matter? In my house, we said: “If you don’t have nothing nice to say, don’t say nothing.” It goes beyond that, though. Don’t think nothing! Just be blank! That hate isn’t adding anything to the world that’s worthy or true. And if you do say something nice, you should mean it fully.

CG: Animals often play a role in your visuals. Your love letter to lowrider culture, “PIRATE RADIO*”, also co-stars a fawn and an owl.

JD: Without it being over complicated, I am interested in creating a sense of familiarity in unfamiliar places, or in placing familiar characters, animals or objects in environments that are not familiar to them. The “PIRATE RADIO*” video calls back to my Dad’s upbringing. He grew up in a very specific part of Long Beach with very specific friends that were very specific colors. Part of that was embedded in my childhood as well. In the video you see one of my brothers sitting in his father’s vehicle. His dad unfortunately passed away, but he left this tradition behind. For us, this is so much more than just two dudes bouncing in a car. It’s representative of that culture and connection. Instead of telling the story of that community in a traditional way, I wanted to speak about a component of our reality that is rarely discussed.

Often pitbulls are incorporated into music videos in a way that makes them look scary. That breaks my heart because I know people will believe that’s how those dogs are in real life. I’ve always had pitbulls and they’re the most loveable dogs. In PIRATE RADIO*, in the place where you might expect to see a pitbull, there’s a fawn. Although my friends and I grew up in tough places and perform masculinity, our nature is as delicate and fragile as those little deers. You’ll also see my homie holding an owl in that video. After shooting, he told me that he had a spiritual experience, in being so close to that animal. When you combine these two things from totally separate contexts, you often realize they’re way more the same than they are different.

CG: There are a lot of parallels between the perception of pitbulls and the harmful stereotypes that have been manufactured about the cultures and communities that you belong to. If a dog is trained to fight and must do so to ensure its survival, the world’s perception of it as a fighter is not a reflection of who it is in its essence, but rather of its circumstances.

JD: It’s the same with us. We’re delicate, we’re fragile, we’re emotive, but we have to put up this big defense. I wasn’t allowed to be soft as a kid. If I was soft, I would have been killed. I had to be strong, I had to be bold and assertive. The older I’ve gotten, the more I’ve broken that down. I know it's a product of my environment and a survival mechanism, but I also know that defense disintegrates my inner child – which I believe is one of the most important tools we have as creatives.

As we get older, our imagination slowly but surely dissipates within the fabric of our daily reality. Keeping the imagination of my seven-year-old self alive is very important to me, not because I want to be childish, but because I don’t want to lose my curiosity. I want people to see themselves in that curiosity. When they see a lowrider and an owl together, I want them to ask themselves: “Why does this feel right?”

I think surrealism allows us to express the ideas that we keep closest to our chests, and to shed light on certain things that we negate. I believe everything has to mean something. he visual component of my work is the most visceral version of that. There are so many symbols and references that I know people will miss. To me, it’s not important that people figure it out as much as it is that they become interested in understanding something outside of themselves.

Me as a person? I mean, cool, whatever. I sit in my room, I watch Deadliest Catch, I paint and draw on my shoes. The things that I am trying to articulate, I hope, are far more important.

Credits

- Text: Cassidy George

- Photography: Nico Hernandez

- Video Stills: Bradley J. Calder