JACK PIERSON

Since moving to New York from Boston in the 1980s, JACK PIERSON has developed an iconoclastic body of work spanning a wide range of media. In December 2006, the artist had his Berlin gallery debut, with simultaneous shows at Galerie Aurel Scheibler and Galerie Neu. The show at Aurel Scheibler focused largely on work from his early years, while Galerie Neu featured a collaborative exhibition with artist Tom Burr. Reflecting on these events, David Velasco sat down with Jack Pierson to discuss Berlin, Warhol’s ghost, and the meaning of gay art.

DAVID VELASCO: Did Tom Burr approach you or vice versa?

JACK PIERSON: We both just thought, “One of these days we should do a show together.” We’d always been in each other’s periphery. It was good because I felt he was doing little versions of my work that were also the roots of work in my show.

One review mentioned that Burr’s homage to your work Silver Jackie at Galerie Neu was missing the traditional cigarette stubs. Is that a reference to you recently giving up smoking?

Probably not. He did that installation at the Whitney [Biennial] a few years ago where there were ashtrays. Up until then I would have said that his work was almost like mine, but more didactic … maybe not didactic, but …

More neat?

Or just more finished. He told me that it’s because it’s all fabricated in Germany. Those early stage pieces I did myself – and I’m not a woodworker – so they have a real slapdash quality. He’s more like a Judd. So I wouldn’t think he’d have cigarette butts, but there they were in that piece at the Whitney.

It seems strange that you just now had your first Berlin show, since Berlin seems like a perfect setting for your work.

I guess I’ve never courted it because … there’s no way to say it that’s not going to sound bad. I’m just not dying to be in Berlin, so I wouldn’t have bothered to do it. Aurel [Scheibler] just moved there. So that was part of the impetus. But I don’t know … it’s far. All cities are probably great – and I had a really good time there – but again, maybe if I still smoked I would like it? They really smoke there. I found it horrendous. For a minute when I first got to art school, and was maybe twenty or twenty-one, I was all up in Fassbinder and I thought all things German were cool. But now I don’t. I mean, Sigmar Polke is probably my favorite painter, but I still don’t have that big of a German thing.

“Oh, you don’t have to make art, you can just be art.”

You don’t have a crush on Berlin?

Oof, no. I mean, I know all those people that do. But to me it’s like, aye aye aye. I could never stay there that long.

But it seems like such a gay city.

I guess, yeah. That’s nice, right?

Lots of underground elements …

But that’s all way too late at night for me. I want to be in bed by midnight.

During a recent talk with Ryan McGinley at New York’s ISE Cultural Foundation, you mentioned something Jeff Koons said about photography being gay and painting being straight.

Well he probably didn’t even say gay or straight. He said homosexual and heterosexual. It was during a little preview/interview when he was preparing to debut those porno paintings of him and Cicciolina, Made in Heaven, which clearly look like photographs. He was explaining why it was important for him that they be paint as opposed to photographs, because painting is in the heterosexual hegemony. They were lasting and about staying, and photographs were more ephemeral, and about nostalgia and impermanence, and therefore, they were more homosexual. I was at a social event with him somewhere, and I brought that up, and he was like, “I never said anything like that.” But who knows, maybe somebody wrote his material for him back then, and he didn’t even know.

Of course in photography you also have a heterosexual canon with Henri-Cartier Bresson and Richard Avedon and Helmut Newton …

Well Richard Avedon … I think that’s negotiable as to whether that was so … heterosexual. I don’t think he ever came out, but I get the impression he was gay. But still, the same with painting. There’s, like, Michelangelo and all those. Was he the only gay painter? Caravaggio and Michelangelo?

You recently said that you don’t think you’re that good at photography.

Yeah, not that good consistently. Or at least these days. I have been in the past, and that’s when I have a huge pool of stuff to pull one image from. I am a homemade photographer, even though certain people will hire me to do things, because I have a book of photographs, so I must be a photographer. But I’m not that kind of photographer that’s like, “Oh here’s a contact sheet, which one do you like?” It’s usually like, just one good one. And usually that one is the one that’s too sad to put in the magazine.

Do you shoot often for magazines?

Sometimes – I used to pursue it more. When I was doing all those boys I was in this zone where I wanted to be shooting for a magazine, and I wanted everybody to be happy. Then I just … I don’t know. Now I do the word pieces. I like being by myself.

“I can’t resist an old movie star and I can’t resist a little bit of camp.”

Seeing your earlier work at Aurel Scheibler together with the newer stuff at Galerie Neu, do you think you’ve gotten better as an artist?

My psychology is so deeply imbued with regret that if I thought about it I would say, no, I’ve gotten worse, much worse. So I don’t want to consider it that much.

It seems like you’re more embracing of the variation of your practice. You can do good stuff, or you can do shitty stuff, but it’s all still yours.

Well, it’s not even good or shitty … I’m not just an artist. I’m also a fan. So to me, if this was an envelope [grabs envelope] and Picasso wrote it out, I would still be like, “Oh my God, Picasso wrote this envelope. Can you believe that?” Or whoever. Ida Lupino. I like that kind of stuff. To me it’s equal to the art. This from a person who hasn’t set out to make any masterpieces.

Thinking of yourself as a professional fan, what’s your relationship to people who have been influenced by your work?

My work has always been about letting people know their art is around them already. So many of my ideas are just things I would think of stoned at a nightclub and be like, “Oh that looks cool. That should be in a gallery.” Because my thing has been so broad, and because I like to keep the touch so loose and not highly evolved, more things can look like I had influence than probably I did. For a long period, until I was like thirty, I felt like, “Oh, you don’t have to make art, you can just be art…” I was in the midst of, “who wants to …”

… have a rigorous practice.

Yeah.

It’s very Warholian.

To have a rigorous practice?

No. The opposite.

But he had a rigorous practice. He worked hard and was very disciplined. And it paid off. And part of my whole mentality is that he and Picasso did it all so well, that it really gave me the possibility of wasting big sections of my life.

As somebody who seems to admit regret, do you regret not having a disciplined practice?

Well who knows … no. Yeah, a little bit. It can always start. I thought at forty I would do that. Like, okay, now everything you’ve seen so far is junk, and now I’m gonna do this. And I’m still working toward that, on a certain level. But I’m not competing with history. I’m not going to reinvent the wheel.

Right, it’s not part of a masculinist heroics or Protestant ethic.

And I don’t think Picasso or Warhol were that either. I like a [Gerhard] Richter painting probably… they’re all fine. But I don’t think there’s anything that Richter does, will do, or cares to do, that hasn’t been done perfectly well by Warhol. So basically, he’s staying busy, making nice things, and living. You can be Richter, and you can paint, and have a simple ploughman’s lunch, and publish a book, but whatever… give me a piss painting or a Rorschach painting, and then a disaster painting, and you’ve got everything Richter’s putting out.

So the specter of Warhol doesn’t haunt you – it’s almost a relief.

Yeah … but I’m not Warholian. Early on, people would say that as code for gayness or something.

You curated a show last summer at Paul Kasmin in New York called The Name of This Show Is Not: Gay Art Now.Why did you choose that title?

I don’t know, I just thought it would look good in an ad for Artforum: “Gay Art Now.” Because it’s like, “Ick, what’s that gonna be? I don’t want to be in that show.” But, I did want it to be about gay art now. So it was both. I had my cake and ate it too. Again, it’s one of those things where maybe I throw away brilliant opportunities to have impact.

Do you think of yourself as a “gay artist”?

No, but I get what they mean. I cannot resist a handsome boy. And I want that to be a part of my thing – I can’t resist an old movie star and I can’t resist a little bit of camp. So yeah, I guess I am, but at the same time I don’t think …

… that it’s the definition of your oeuvre. I had a thought coming in here, that maybe glamour is your medium and nostalgia is your style.

It is nostalgic. You’re not supposed to say that though. I think it’s because I grew up with older parents maybe.

You learned to value older things.

Now that I’m in the happy luxury of other people owning my little peculiarities, I feel like I’m so uninvested in objects. Before I moved to New York I collected records like crazy. Now with the Internet, all that stuff is catalogued. Good, one less thing. Now let’s go and be free of that illusion that you can own things – that illusion that paint and paintings and things can save you. I don’t even think my work exists without me on a certain level. I make a thing that – if I put it together – will tug your heartstrings. I get asked, “Oh how should we install it?” Spell it out. Do it how you want. It’s an illusion that these things are worth money. I tend to identify more as a poet, or a performance artist.

You’ve even said before that your installations are sets or stages.

Right. I think that’s it. But I would never make you come and sit through a performance, not in a million years.

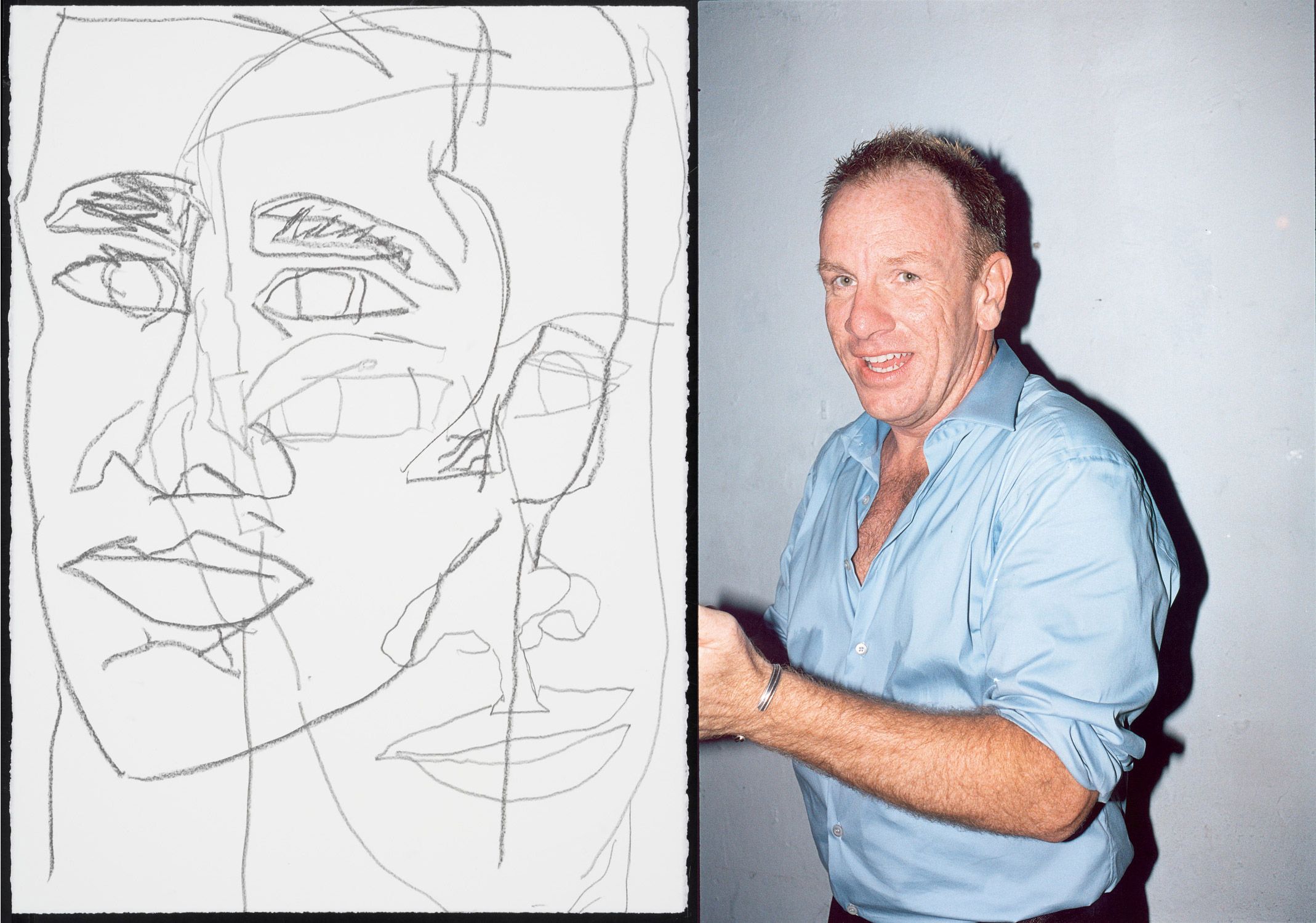

Interview by DAVID VELASCO, Portrait Photography LUKAS WASSMANN