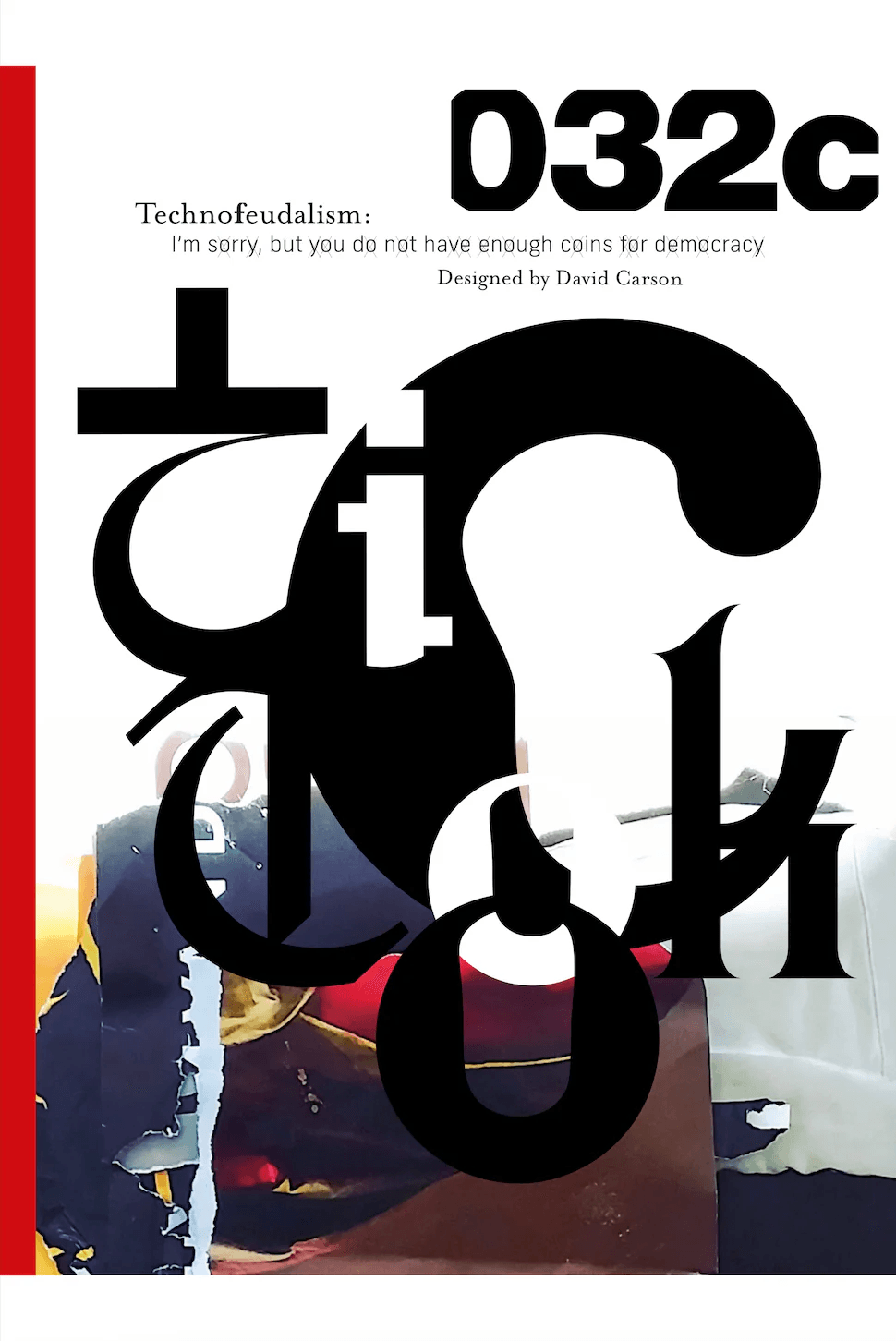

I’m sorry, but you do not have enough coins for democracy

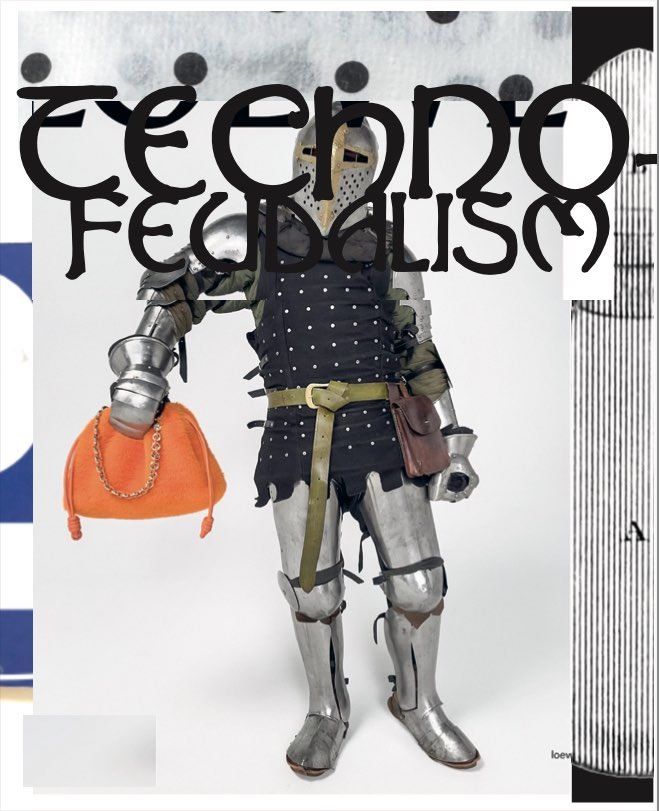

When Trump 2.0 began, he invited some of the world's most powerful technocrats into his court of jesters. Many didn't last long but the foundations were set: the US government would try to run the country like a startup, blockchain coins included. Technofeudalism is a term that's been used to describe the current administration, but what does it mean? Our dossier from the Summer 2025 issue looks at the prehistory of technofeudalism, how the US has changed the operating system, and why the tech bros find inspiration for domination in the medieval.

Design by David Carson

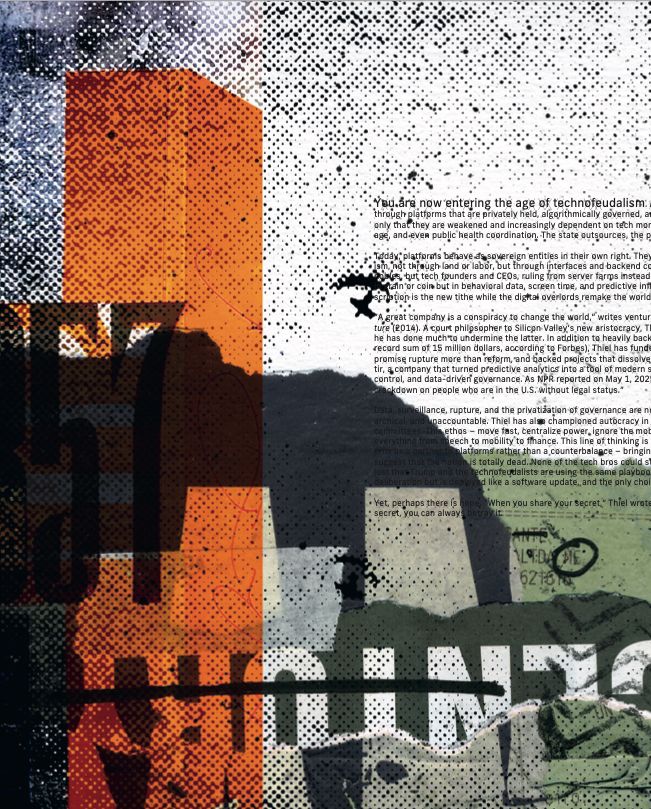

You are now entering the age of technofeudalism.

A system of power that no longer flows through parliaments or the public but through platforms that are privately held, algorithmically governed, and indifferent to democratic consent. It isn’t that democracies no longer exist, only that they are weakened and increasingly dependent on tech monopolists to deliver security infrastructure, communications, logistics, cloud storage, and even public health coordination. The state outsources, the platform scales – and in the murky in-between, a new sovereignty is taking hold.

Today, platforms behave as sovereign entities in their own right. They define rules, enforce compliance, and extract value. It is the rebirth of feudalism, not through land or labor, but through interfaces and backend code. The main difference to the old order is that today’s lords are not landed nobles but tech founders and CEOs, ruling from server farms instead of castles, where they issue code instead of edicts while extracting tribute not in grain or coin but in behavioral data, screen time, and predictive influence. And unlike the serfs of old, we do not own our tools. We lease them. Subscription is the new tithe while the digital overlords remake the world from above – unaccountable, automatic, and everywhere at once.

“A great company is a conspiracy to change the world,” writes venture capitalist Peter Thiel in Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future (2014). A court philosopher to Silicon Valley’s new aristocracy, Thiel has long argued that freedom and democracy are no longer compatible, and he has done much to undermine the latter. In addition to heavily backing his former employee J. D. Vance for his successful Senate run in 2022 (for a record sum of 15 million dollars, according to Forbes), Thiel has funded migrations and surveillance firms, underwritten political campaigns that promise rupture more than reform, and backed projects that dissolve the boundary between governance and infrastructure. Among the latter is Palantir, a company that turned predictive analytics into a tool of modern statecraft, quietly embedding itself in the war on terror, mass policing, border control, and data-driven governance. As NPR reported on May 1, 2025, Palantir is a “key private contract as the [Trump] administration intensifies its crackdown on people who are in the U.S. without legal status.”

Data, surveillance, rupture, and the privatization of governance are not bugs but features in this emerging order, where power is consolidated, hierarchical, and unaccountable. Thiel has also championed autocracy in the corporate form, arguing that startups should be ruled like monarchies, not committees. This ethos – move fast, centralize power, ignore the mob – has become the operating system of the dominant platforms that mediate everything from speech to mobility to finance. This line of thinking is also being adopted by the current US administration, which increasingly governs as a partner to platforms rather than a counterbalance – bringing technofeudalism out of the cloud and into the cabinet. And again, this isn’t to suggest that the nation is totally dead. None of the tech bros could stop Trump from deploying tariffs that would damage their business interests. It’s just that Trump and the technofeudalists are using the same playbook, operating like little Caesars. For them, the future isn’t built through democratic deliberation but is deployed like a software update, and the only choice is to click “accept.”

Yet, perhaps there is hope. “When you share your secret,” Thiel wrote in Zero to One, “the recipient becomes a fellow conspirator.” Once you share the secret, you can always betray it." - Shane Anderson

Dr. Jens Hillebrand Pohl

In this position paper, Dr. Jens Hillebrand Pohl makes a radical suggestion. If America no longer holds itself to traditional democratic norms of nation-ruling, then perhaps citizens, allies, and observers should stop behaving as if it does. According to Hillebrand Pohl, a legal scholar and geoeconomic strategist who heads the Helsinki Geoeconomics consortium, America has not been weakened by the technofeudalist takeover, it has just transitioned into a post-state regime, where traditional democratic institutions and alliances are supplanted by a system where power is exercised through control over digital infrastructure, data, and algorithms. Offering a nuanced perspective of this takeover, Hillebrand Pohl subtly critiques the erosion of democracy and leaves the reader to grapple with the consequences.

Act 1, Dr. Jens Hillebrand Pohl on America.

America Is as Strong as Ever - Just Not as a State

America is not in decline. It is under new ownership.

Its systems still function - but not for the same reasons, or for the same people. What appears incoherent from the outside is, on closer inspection, a consolidation of power under a new regime. America hasn’t collapsed. It has restructured. The result is not weakness - it is strategic freedom.

The United States is no longer governed by the state. It is governed by a ruling network: asset allocators, platform owners, legal tacticians, and media architects. Donald Trump is its apex but not its originator. What binds the members of that network is not ideology but configuration - shared leverage, shared threats, and shared incentives to discard the formalities of institutional rule.

This group is not a hidden cabal. It is the visible infrastructure of power in the 21st century. The American republic remains on paper, but the system has moved on. Foreign policy is no longer authorized by the State Department. Alliances are no longer maintained out of principle. Continuity is no longer a goal. NATO survives because nobody has the heart to bury it.

The ruling class that emerged as kingmakers in late 2024 - what we call the bricolage - has no loyalty to the state form. Its interests are transactional, agile, and sovereign. And it now holds the reins of what was once the state.

By bricolage, we do not mean a cultural cliché. We mean a post-institutional elite: platform executives, surveillance capitalists, justification engineers, and information strategists. They govern America with sovereign funds, govern capital - through access, algorithms, and withdrawal of support.

America today is not acting like a democracy in crisis. It is acting like a post-state superpower in control.

It no longer needs procedural continuity, institutional legitimacy, or allied compliance. It no longer needs its allies - because it no longer needs the state.

This essay charts the rise of America’s post-state regime: how it emerged, what it controls, and why its power will probably define the geopolitical horizon of the next decade. This story is not about failure. It is a story about evolution.

This is not the end of American power. It is its distillation. America has not lost its position - it has changed its operating system.

II. Strategic Contraction and the End of Obligations

The United States is not withdrawing from the world because thenation is overstretched. It is shedding obligations because they no longer serve its core power structure.

This is not imperial decline. It is strategic divestment.

America has become a post-state superpower. Its sovereign priorities are no longer the priorities of the nation-state. It no longer depends on permanent alliances, multilateral bureaucracies, or legacy partnerships to project power. In fact, these old ties now obstruct the operational freedom of its post-state regime.

The process is deliberate. Military treaties are quietly deprioritized. Trade agreements are left unrenewed. International forums are attended out of habit, not necessity. What looks like disinterest is, in reality, sovereign unbinding. The United States is not collapsing. It is exiting structures that assume it is still a state.

Foreign policy, as traditionally understood, is dead. The logic of alliances - mutual commitment, procedural continuity, shared costs - is incompatible with a regime that now operates through tactical leverage and conditional loyalty.

This is why America no longer behaves like a guarantor of global order. Its military footprint contracts. Its diplomatic tone hardens. Its partners - Canada, Germany, Australia - are treated not as peers but as slow-moving stakeholders in a structure the regime no longer intends to maintain.

NATO survives, but it is hollow. American support is no longer assumed - it must be negotiated, and even then, it might not arrive. The alliance still flies the flag, but it no longer sets the rules. The alliance is not being disbanded. It is being devalued. Even defense spending, often used as the signal of seriousness, is being redefined. The cuts are not about peace. They are about power efficiency. Cutting the defense budget is not about making America weaker. It is about eliminating waste, disempowering rivals, and reallocating capital to sovereign-aligned innovation.

America’s regime is no longer interested in sustaining industrial-era defense monopolies whose primary constituency is federal job preservation. The legacy contractors - Boeing, Lockheed, Raytheon - are being phased out, not because they are obsolete, but because they are loyal to the wrong machinery.

The new sovereigns - SpaceX, Palantir, Anduril - don’t require lobbying or patriotism. They require access. They provide capabilities that are aligned with the post-state logic: software-defined kill chains, orbital dominance, data fusion. They do not slow down the system. They accelerate it. The goal is not to weaken America. It is to rebuild sovereign capacity outside the old order.

Strategic contraction is not the abandonment of power. It is the optimization of its velocity.

America is not burning bridges. It is cutting dead weight.

III. Sovereign Capital Logic - From State to Actor

The United States is no longer governed by its institutions. It is operated by its capital structure. The American state - what remains of it - serves not as the source of authority but as the shell through which a ruling network now governs. This network does not reside in Washington. It resides in jurisdictions, in holdings, in nodes of influence and infrastructure. It consists of people who understand that to command the system, you do not need to reform it - you need to outgrow it.

America no longer behaves like a state. It behaves fusion. They do not slow down the system. They accelerate it. The goal is not to weaken America. It is to rebuild sovereign capacity outside the old order. Strategic contraction is not the abandonment of power. It is the optimization of its velocity. America is not burning bridges. It is cutting dead weight.

Axiom I: The Reversal of Sovereignty

Sovereignty in the post-state order no longer resides in the state. It resides in the ruler, understood as the apex node of an oligarchic network. This is not populism. It is not elite conspiracy. It is structural realignment. In the United States, the central figure of this network is Donald Trump - not as a lone actor, but as a command interface. The true regime is broader: Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Larry Ellison, and others who control infrastructure, capital, sovereign service providers, and narrative systems. Their loyalty is not to the republic. It is to one another, and to the system they now operate. This is not governance. It is authorship. Laws are optional. The state is a wrapper. The system functions for those who write its code.

This is what makes America different. Other nations still depend on bureaucracies, coalitions, and legal continuity. America no longer does. It has become the first post-state regime in modern history - a configuration of power that governs without pretending to be a government. What matters now is not legitimacy. What matters is leverage. The United States is not run by a president. It is run by a network. Trump is not a steward of American law. He is a director of its assets.

IV. Ruler-to-Ruler Engagement - Diplomacy After the State

Diplomacy was once conducted between states. It presumed continuity, memory, and shared constraints. Leaders changed, but the state endured. Alliances were maintained by institutions, not by personalities.

Historical Sidebar: Statehood as Innovation

What we now call states were not the default mode of political organization. For most of human history, power was exercised through tribes, dynasties, cults, clans, courts, and feudal networks. The modern state - defined by bureaucracy, territory, and impersonal rule - is a relatively late invention that emerged only in the early modern period. Among European powers, France stands as a case study in early statehood. It was one of the first to consolidate feudal territories, centralize taxation, impose linguistic and legal uniformity, and assert that sovereignty lay not in the person of the king but in the apparatus of the state itself. From this emerged the expectation that diplomacy, warfare, and law would be conducted not by rulers, but by offices. That historical shift - from ruler to state - is now being reversed.

That logic no longer applies. In the post-state world, diplomacy is not state to state. It is ruler to ruler. The United States does not engage governments. It engages people who rule. It does not value democratic legitimacy. It values operational coherence. What matters is not the system you represent but whether you can make a deal - and make it stick.

This is why Trump’s America courts Narendra Modi,Viktor Orbán, Mohammed bin Salman, and Benjamin Netanyahu. Not because they are democrats,but because they are sovereigns - not bound by bureaucratic drag, not constrained by procedural oversight, and not interested in virtue signaling. They get things done. That is the point.

Canada, Germany, and Australia still send their prime ministers. America does not respond. Not because it is absent, but because it is not interested in middle management. If your government depends on parliamentary coalitions and polling averages, you are not a strategic peer - you are a client.

Even when the US remains formally inside multilateral agreements, its behavior has changed. Treaties are reversible. Obligations are flexible. Summits are theater. The real decisions happen off platform: in private channels, in encrypted networks, in backchannel alignments between rulers who understand the game. The handshake is more important than the communiqué. The photo op replaces the policy paper.

America no longer offers continuity. It offers terms. This is not isolationism. It is power without performance. It is not empire. It is access control. What used to be foreign policy has become sovereign pattern-matching. The only question that matters is: are you someone we can work with? If not, you are ignored. If so, you are invited inside the bandwidth.

V. From Post-Westphalian to Post-State

The modern state was never the default. It was a historical detour that briefly held together the fiction of institutional sovereignty. Before the state, power was personal. Dynastic, cultic, feudal, tribal - always tied to people, not procedures. Then Westphalia imposed a fix: territory equals legitimacy, and institutions speak for the people. That patch lasted a few hundred years. It is now obsolete.

The post-WWII liberal international order - UN, IMF, NATO, EU - was a Westphalian remix. States were still the players. But sovereignty was softened by norms, layered with rules, and globalized through systems. That structure has collapsed. Not in theory, but in function.

America is not fighting to preserve the old order. It has moved on. The state has not vanished. It still flies the flag, holds elections, and ratifies agreements. But the real machinery of sovereignty has decoupled from government. It runs through platforms, capital networks, data infrastructures, and private systems of enforcement. This is not a bug. It is the new operating system.

Power now flows through stacks:

- Symbolic sovereignty (flags, courts, armies)

- Platform sovereignty (communications, accounts, visibility)

- Capital sovereignty (access, liquidity, immunity)

- Narrative sovereignty (legitimacy, alignment, orthodoxy)

You do not need to control all layers. You need only to author the ones that matter in your domain. And America’s post-state regime is already doing that - with brutal efficiency. This is not a return to monarchy. It is not anarchocapitalism. It is post-state logic: coherence without accountability, reach without responsibility, force without formality. The rest of the world still speaks the language of states. America has switched codes.

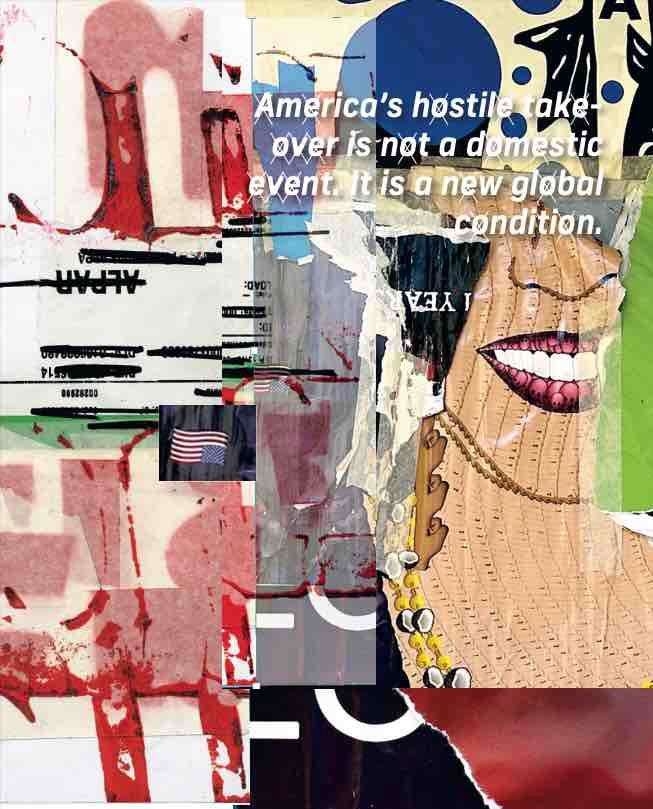

VI. Strategic Implications

America’s hostile takeover is not a domestic event. It is a new global condition. The world continues to talk in state-language: representation, law, multilateralism, collective security. But those terms are no longer operational. America doesn’t play that game anymore. It plays a different one - and others will have to adjust or be left behind.

This section outlines what that means for everyone else.

For States: Legacy Power, Structural Vulnerability

If your sovereignty still runs through ministries, treaties, or elections, you are not in the game - you are watching from the bench. States that cling to institutional legitimacy as their strategic asset are mistaking nostalgia for leverage. America no longer respects continuity. It respects optionality. If your government cannot pivot, cannot enforce, and cannot act without consultation, you are not a partner. You are a node waiting to be rerouted.

To remain relevant, states must:

- Operate across legal and technological jurisdictions simultaneously

- Develop internal foreign policy - how they relate to the broligarchy, not just to governments

- Build their own infrastructure of autonomy - communications, energy, intelligence, narrative systems

France once became the first state in a continent of royal domains. Now, America has become the first post-state superpower in a world still trapped in institutional fantasy. That’s not an accident. That’s a power curve.

For Firms: You Already Have Sovereignty - Use It

Corporations now command territory-independent assets, enforce compliance without law, and control more infrastructure than most states. They are sovereign. The only question is whether they know it.

The post-state order rewards the firm that acts like a polity:

- Building its own diplomatic alignment

- Structuring jurisdictional strategy like a portfolio

- Withdrawing from regulatory frameworks that no longer deliver value

The playbook is simple: don’t ask for permission - build what others will depend on. Those who wait for stable governance will be governed. Those who build the stack will rule it.

For Individuals: Agency Is a Structure, Not a Feeling The age of the citizen is over. The individual’s only hope for agency now lies in how strategically they position themselves within the new structure.

This means:

- Acquiring jurisdictional agility - residencies, accounts, reputational insulation

- Cultivating narrative capital - platform visibility, symbolic resilience, brand-level identity

- Protecting optionality - moving, hiding, signaling, withdrawing In the post-state order, your dignity is not a right. It is a strategy.

The Meta-Strategic Lesson

Coherence is no longer rewarded. Authorship is.

- The state that dominates will be the one that rewrites the framework.

- The firm that thrives will be the one that designs the environment of exchange.

- The individual who matters will be the one who can operate across layers of the stack, not within the rules of a vanished republic.

The future belongs to those who know how the system works - and know how to walk away from it when it doesn’t.

VII. The United States as a Post-State Sovereign

America has not collapsed. It has changed shape. The republic still exists in form - elections are held, courts convene, laws are cited - but the real source of power has migrated. It no longer flows through representation, legality, or public legitimacy. It flows through control: of infrastructure, access, attention, and enforcement.

This is not dysfunction. It is realignment. The American state, as a governing institution, is inert. But the American regime - as a sovereign system - is fully operational. It simply no longer answers to the state. It answers to itself. That regime is not elected. It is configured. Its architecture includes Donald Trump, but it also includes Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Larry Ellison, and a host of aligned sovereign firms. It is not ideological. It is logistical. It does not govern to serve. It governs to execute. The American post-state regime thinks like a platform. It offers access, scalability, and enforcement. It filters participants. It denies support. It operatesthrough infrastructure, not ideology.

What matters now is not who holds office, but who holds the stack.

In this configuration:

- Policy is delivered through executive fiat or private coordination.

- Narrative is managed through platform alignment, not journalism.

- Legitimacy is irrelevant unless it translates to leverage.

What makes America unique is not that it abandoned the republic. It is that it did so without losing control. The regime took the tools and left the paperwork. That’s what a post-state sovereign looks like: not failed, not anarchic, but fully integrated and no longer pretending. The world is still waiting for the American government to return to normal. But America has already moved on. The state is still here. It just doesn’t matter anymore.

VIII. The Strategic Horizon

The state is not the future. It is the past. America has not exited global power. It has exited the operating system through which that power used to be managed. What looks like collapse is in fact control - recentralized, reconfigured, and rerouted through a sovereign class that no longer needs the illusion of institutional legitimacy to act. This is not dysfunction. It is authorship.

The American broligarchy has no need for alliances, because it no longer seeks consensus. It does not require international law, because it does not ask for permission. It has no loyalty to institutions, because it governs through networks. It is not interested in the system. It is writing the next one. This transformation is not an aberration. It is the

template. Other states may follow, or fight it, or flail in irrelevance. But the shape of sovereignty has changed - and the prototype is already operational.

Axiom II: Authorship Is Sovereignty

Power in the post-state world is not held. It is designed. The sovereign is not the entity that governs. It is the entity that writes the rules of governance - and exits them at will.

America no longer manages international order. It instructs it. It no longer offers stability. It offers access. It no longer claims legitimacy. It demands relevance. The United States is no longer a state. It is a sovereign platform - and the first of its kind.

The rest of the world must now decide: Will you continue speaking in the language of treaties, institutions, and elections? Or will you learn to speak in code?

Because America already has.

Act 2, Cédric Durand interviewed by Shane Anderson

The French political economist Cédric Durand

might be a modern Nostradamus. Five years before Trump started gutting the government and sidling up with his new ally Elon Musk, Durand predicted a technofeudalist future, where technology monopolies wielded more power than government institutions. Originally published in France as Technoféodalisme: Critique de l’économie numérique by Éditions La Découverte, it was released by Verso in the summer of 2024 as How Silicon Valley Unleashed Techno- Feudalism and charts how information and data networks are driving a change in system, heading toward a new economic order where capital focuses on predation rather than production. In this interview from March 2025, Durand gives a brief history of how Silicon Valley abandoned its utopian democratic ideals for autocratic tendencies and explains why boredom might be the mood that saves us all.

Shane Anderson: Your book came out in French in 2020, but its relevance has really skyrocketed recently -

Cédric Durand: It’s incredible, isn’t it? It’s wild when something you were surmising becomes real.

SA: Back then, you suggested that a change of systemic logic was taking place that was being ignored due to capitalism’s overlapping crises. What is this systemic change?

CD: We are moving away from a system dominated by competition and innovation for profit whose underlying logic is oriented toward production. Previously, capitalists had to invest to improve productivity, which led to increased production. But now, the system is increasingly stagnant. That doesn’t mean there isn’t innovation anymore, just that it isn’t really oriented toward production. It’s more oriented toward control and the cen tralization of the means of coordination. This form of innovation changes a lot of things. There’s less competition and more monopolies, on the one hand, and less productive dy namics and more zerosum game predation, on the other. This is the trend we are observ ing, and it’s the result of institutions and political decisionmaking.

SA: But aren’t there innovations aimed at productivity and production? I’m thinking of the AI boom and ChatGPT being used by coders - and everyone else.

CD: While they’re not really aimed at control per se, it’s nevertheless about the data that is gathered from people using AI tools, which run on huge cloud servers run by monopolies. There aren’t many dominant actors in that sphere - there’s just Amazon, Google, and Microsoft - and centralizing knowledge is a way for them to gain control. And they’re growingat Yahoo! who really believed that they were going to change society in size and power. Control not only plays a role here, in that they learn from the people who use AI - and the more people use [it], the more they learn - but they also impose guidelines. These tools are curated; they organize and restrict access to knowledge. To some extent, this is also controlling the way people act, consume, and produce.

SA: Like the internet, these tools promise more freedom, but in your view, they are designed with control in mind. When were the utopian promises of digital life relinquished?

CD: Technooptimism was a Silicon Valley story, of course. There were also leftist read ings of it, suggesting that a historical opportunity was opening for progressive forces. People like [Antonio] Negri, saying that the multitude was organized by knowledge that was free, but what started to appear during the stagnation in the early 2000s was not that optimistic. There were a lot of problems, actually. Startups, for example, were not pro posing a rejuvenation of capitalism, nor were they allowing labor to be freer and more creative. In fact, they were very harsh on their workers, with high levels of supervision. There are many instances, including Amazon’s worker cage, a patent that was made, and enterprises like Sayint - which was backed by Microsoft - who now supervise 100 percent of the teleworkers in call centers, which wasn’t the case before. I will say that, up to the early 90s, there was a truly progressive, semihippie, semiantiauthoritarian stance that was supporting the advance of international technology, with people engaged in selfproduction and coopera tion in writing software. This aspiration exists to some extent today in vibrant communities of free software. But the tide has drastically shifted. At some point in the [1990s], there was an alliance built between decisive parts of the tech crowd who had been very anti authoritarian and people on the right who were very promarket, very against the involvement of state in economic management. This alliance created the new economy in the 90s, and it later became a data monopoly in the 2010s, when property rights were enforced. An important figure here is Ayn Rand. She basically gave these en trepreneurs the idea that they have all the rights and that they do not have to respect any rules because they are a kind of Supermen; they can just break everything, since they’re moving very fast.

SA: Were the progressive tendencies of Silicon Valley really over by the mid-90s? I came up in the Bay Area rave scene in the early 2000s, and back then, almost half of the people in the various crews worked in the dot-com world, and they all still held on to semi-hippie, anti-authoritarian views. I had friends who worked at Yahoo! who really believed that they were going to change society for the better . even if they mostly just played video games all day in their “lab.”

CD: Maybe the picture I painted was too dark. I don’t know what it was like on the ground in Silicon Valley, but on an institutional level, the US government decided to aggressively fight alongside these new corporations against any kind of corporate regulation at the interna tional level. Newt Gingrich even said that this was a way to reassert the dominance of the US.

SA: So, what’s the narrative? We’ve awoken from the dream of democratization and found ourselves in the nightmare of feudalism?

CD: There’s one step missing there, which is the process of mo nopolization. With the strong protection of individual property rights, there was a lack of regulation, which prevented the general public from getting access to data. This enclosure of cyberspace was actively pursued by probusiness organizations like the Progress and Freedom Foundation, who found a way to shape the nascent global digital economy via the Clinton administration. It was also supported by neo-Schumpeterian economists, such as Philippe Aghion, and OECD reports that argued that protecting innovation rents via strict intellectual property rights and low taxes on capital was crucial to foster prosperity.

There’s another crucial economic aspect, though, which is the double process of increasing returns. First, you have infinite returns to scale that are related to intangibles. For example, when you write a software or make a video, you can diffuse it at almost zero cost, which gives advantage to the first mover. But then, as I mentioned, it’s increasingly difficult to get access to original data, which prevents others from entering the game. There are then decreasing returns, which is similar to getting access to oil. The combination of infinite return to scales that gives a huge advantage to the first mover and the strong nega tive return to scale in terms of getting access to data is at the root of this process of running to scale. I think it’s very impor tant to understand the economics of that. Think of Google: first, they created a smart search algorithm that they were able to deploy at a very large scale without much expense once its core parameters were designed (infinite return to scale). And then, they fought very hard to get access to original scarce sources of data: your phone. This is the rationale for Android. Putting Android in phones with Google apps by default is dig ging data wells in the space of social activity, a space which is limited, [and] thus absolutely scarce, just like land.

SA: What does this have to do with feudalism?

CD: Feudalism is completely different from technofeudalism, in that peasants worked with their own tools and brought some of their products to the lords. They effectively worked a couple of days for the lords, but the dominant form of their labor process was solitary or familial. In technofeudalism, there is a massive socialization of labor, and the digital world plays a very important role in the increasing socialization.

Two crucial dimensions to technofeudalism echo the medieval times. The first is similar to feudalism in that there is a relation of dependency both politically and economically. To put it sim ply, our dependency today draws from the fact that no one can live without Google or Microsoft. I mean, my mother can, but she’s 82 years old. To her, it isn’t a drama if she cannot access Google, but it is for most of us. That’s an obvious fact of depen dency, but it goes further. Think about states. Nations are increasingly reliant on these technofeudalists. There is a lot of literature on how these firms are providing crucial infrastructure to the operations of states and their communication networks. Take for instance the submarine cables. Up until the 2000s, they were state owned. But now most of them are owned by private corporations. The same goes for cloud services. The German ministry signed a contract with AWS [Amazon Web Services] for its cloud last November, for example. Private companies are playing crucial roles for the operations of the world, which means that the sovereignty of the state is in decline; they’re subordinated to corporations. Other companies are dependent on them, as well. Even large companies like Walmart rely on their cloud services, which means that these cloud monopolists are taking an increasing share of value created along the chain. And this is what’s so strange. In the beginning, Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Tesla were all completely different companies. They weren’t in the same business. They were selling books or a search engine or word processing or cars. But now, they’re all converging towards the monopolization of the means of coordination. And that’s how we’re going back to feudalism. They are monopolizing something that nobody can escape. They’re both curating that space and regulating it. That has a political aspect but also an economic one, since they can make money out of it.

SA: Perhaps this is a detour, but how did feudalism end?

CD: It ended thanks to trade routes and the ability of the glebe to escape from the

dependence on the territorialized fusion of economic and political power. The

transformation between the lords and the peasants then changed from one of pure domination towards market relations, which entailed a move towards productivity.

SA: If trade routes brought the end to feudalism, then this also had to do with the spread of goods and communication, right? But now, all the trade routes are owned by these companies. Would you then say that the root of all evils is a consequence of decades of privatization with no market regulation?

CD: I think that’s a very good way of summarizing the increasing retreat of state

legitimacy and action. One of the biggest errors of policymakers was to say, “Okay,let’s see what they can do. Let’s trust them. Let’s follow them.” As a matter of fact, that was exactly the same error that was made visàvis the financial industry. Before 2008, there was this very complex financial product, and at the end of the day, nobody was able to regulate it because nobody understood what was happening. It’s a similar process. And so, if there’s a lesson to be taken from that, it’s that it is very important for the state apparatus – the public entities, the commons, or whatever you want to call it – to retain competencies to understand what’s being done.

SA: Isn’t this related to the high degree of specialization in industries?

CD: I agree that there is an increasing sophistication linked to specialization that makes it difficult for people in separate fields to engage with one another, but I don’t think that has any kind of implication for the organizing of states. You can have public bodies where people are able to understand what is going on and are talking with one another. There is the idea of an academic nation, where some people are able to articulate the discussion, and there is the idea of innovation systems that link the private and public sectors. There are people who are able to build bridges and help organize the institutions. This is more costly, of course, as you need more and more institutions. But we shouldn’t have a fatalistic view on this. Do you remember Libra?

SA: No.

CD: It was a project to have a currency on Facebook in 2019. Can you imag- ine? It would have been incredible. The single most widely used currency in the world. But policymakers and foreign bankers said, “No way.” That entity would have too much power. Libra was stopped. And so, we can stop things like this. Another positive example is China. They’re at the frontier of tech, but they’re regulating it. They discipline their tech bosses. In many Chinese companies, there’s a thing called a golden chair, which is a share that allows you to veto a company’s strategic decisions without your being able to receive dividends. That’s one form of political control, and I think things like this need to be considered.

In the big picture, I think China will appear to be the most reasonable way of dealing with tech businesses in the 21st century. It’s just more stable. They also have a strong ecological agenda, international relations, and think that the private sector should have some supervision. I’m not very enthusiastic about the lack of pluralism, or privacy, and so on and so forth there. It’s not that I like that, but China just seems less crazy.

SA: What do you make of what’s happening in the US?

CD: You know, I used to play music and read novels, but for the past months I have not been able to, because it takes too much energy, trying to make sense of what’s happening. My interpretation is that they’re really trying to concretize this hypothesis of technofeudalism. They’re weaken- ing the state, transferring the state’s capabilities to the private sector, and giving more space to it. It’s completely incredible, for instance, that on the first day Trump took office, he signed an executive order suspending the federal state’s supervision of AI. Then, of course, there’s DOGE [Department of Government Efficiency], which [has been] weakening regulation capabilities and screening civil servants who would resist the companies’ power. They’re really trying to implement technofeudalism and allowing companies to build their own sovereign space without any limitations imposed by the state. It will fail, however. That’s my hypothesis. Managing society without political mediation is simply too complex. Then, at the international level, people are al- ready reacting, and this will increase. There will be a reinforcement of state capabilities. I’m not that pessimistic, to be honest, because I do not think they will succeed. They’re trying, though.

SA: You aren’t nervous? I mean, isn’t this exactly what they set out to do with Project 2025?

CD: There’s a plan, for sure. And it’s a very systematic dismantling to create confusion -

SA: There was a recent article on the New Yorker website, where they used the term technofascism in relation to what’s happening in the US. Would you agree with that?

CD: While it is true that there is instrumental racism that is heading towards neofascist tendencies, such weakening of the state apparatus is not the logic of fascism. The logic of fascism is to reorganize the state against the labor movement, not the dismantling of it. Nevertheless, there is a link to fascism, but there is something new that is linked to the willingness to control and dominate directly, without the mediation of the state. Technofascism also neglects the centrality of monopolization, which I think is very important.

SA: What about in Europe? Do you feel like their governments are technofeudalist?

CD: Europe is not moving towards technofeudalism, because there are no big tech lords in Europe. Instead, Europe is moving very rapidly to the periphery. There’s [been] a kind of digital colonization of Europe in the past 15 years, and it’s lagging behind the frontiers of development because of the lack of economic strategy. But that doesn’t mean things can’t change. With five years of strong catching up and decisive policymaking, you could attract many scientists from the US who are disgusted by what’s going on there. I don’t think it’s impossible to do that.

SA: So, you don’t think the US’ technofeudalism and digital colonization is here to stay?

CD: I hope not. I think the US will push for that very strongly, and if they are able to make gains under Trump, there will probably be irreversible damage. The federal state will be so weakened. However, I think other countries, like China, will take measures, and other companies will call for their state to step in and protect them. And then, the social basis for the US’ techno agenda is very narrow. You know, if you’re not able to deliver anything in terms of stabilizing the socioeconomic situation of the people, then I don’t think that you’ll be able to gain enough support. Which is why they are manipulating the public sphere. Maybe a war agenda could gain some popular support. And I guess it is this lack of support that does make it fascist and authoritarian. Fascism is, in a sense, instrumental to advance the technofeudalist agenda.

SA: Does this move towards technofeudalism mean the end of capitalism?

CD: My interpretation is really close to what McKenzie Wark explained. Capitalism is still there; it’s not disappearing. It’s just overlapping with these technomonopolists ruling over the rest of society.

SA: Is there any potential for resistance?

CD: There’s the option of total submission, of course. You know, we are so managed by these algorithms that we lack any kind of true agency or ability to react collectively. There is no alternative to the market, since the monopolies are managing us. Nevertheless, I cannot imagine that there won’t be some resistance. One example is that even people in marketing are realizing that, when you manage too many people, they get bored and escape. There has been empirical research with AI, too, where people say they are not satisfied using these tools and that they are bored. And when you’re bored, you’re able to do many interesting things to escape it. I think boredom could be the frontier. There’s the option of total submission, of course. You know, we are so managed by these algorithms that we lack any kind of true agency or ability to react collectively. There is no alternative to the market, since the monopolies are managing us. Nevertheless, I cannot imagine that there won’t be some resistance. One example is that even people in marketing are realizing that, when you manage too many people, they get bored and escape. There has been empirical research with AI, too, where people say they are not satisfied using these tools and that they are bored. And when you’re bored, you’re able to do many interesting things to escape it.

I think boredom could be the frontier.

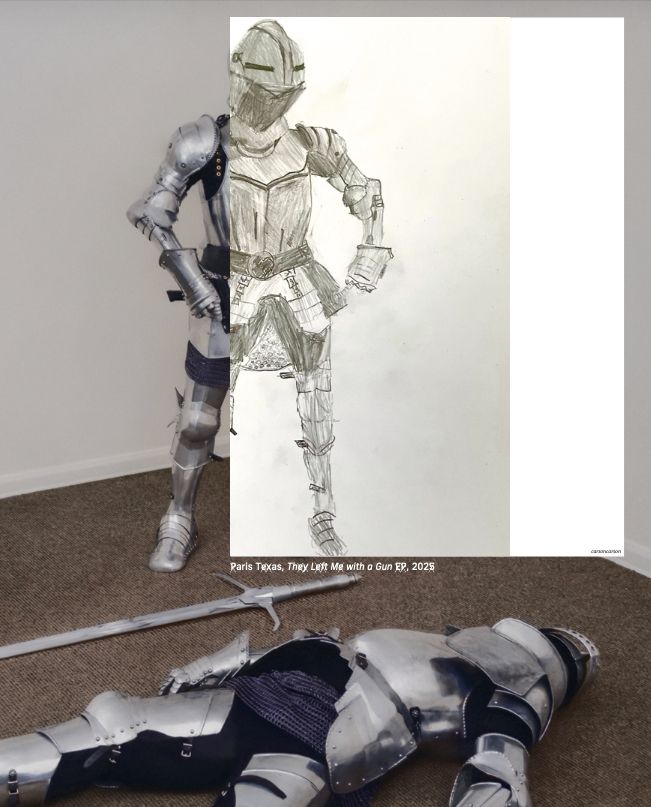

Act 3, Günseli Yalcinkaya "Chain Male Gaze"

“I have changed my mind and am starting a Knightwork State,”

writes Wassim Z. Alsindi. “It's called CAMELOT, and I’m King of it. Become my serf and I will bestow upon you everlasting chain mail, longevity pills, and tax exemption.” With this X post depicting skulls, castles, medieval helmets, and a chalice, Alsindi is mocking the broligarchy’s desire to create “network states” – decentralized and digitally native micronations that have an emphasis on tech-accelerated independence. But Alsindi, who runs Berlin-based 0xSalon and researches the philosophy of blockchain systems, is also mocking the technocrats’ holy trinity of profit, promises of eternal life, and medieval aesthetics – the last of which is a growing trend amongst technofeudalists.

The proposed network state Praxis offers the most literal interpretation of this fantasy medieval aesthetic. Having created Magic: The Gathering–style cards with titles such as “The Pioneer” (courtesy of tech investment firm Bedrock), Praxis makes hyperspecific in-jokes and thinly veiled references to the Knights Templar and other secret societies on X. On August 14, 2024, Dryden Brown, the founder of Praxis, posted an image of an av- erage white guy in full chain mail, surrounded by Praxis Nation flags. Its caption read, “Not sold, only bestowed” – implying that sovereignty can only be passed onto its members, like a coat of arms. Although this provocative post could be written off as an edgelord playing dress-up, it is amplified by Dryden’s cryptic comments about “winds of change” sweeping “through the digital empire.”

Founded in 2019, Praxis positions itself as a “sovereign network” funded by Silicon Valley and built on AI and blockchain. Initially intended to be established on a Mediterranean island, the company has since gone through several rebrands, and Brown is to announce a new location in Q4 of this year. If we’re to believe the promotional material, which can at times read like a five-step pyramid scheme, Praxis has so far raised 500 million dollars from investors. Based on a design by Zaha Hadid Architects, the city features a blend of ancient Greek motifs and futuristic renders – something Brown has described as being “Elon-compatible.” Of those Praxis Society Members who have expressed interest in moving to the city, the company is asking for a 5,000 dollar deposit. Interested parties can apply for a permanent “steel visa” that promises its citizens tax advantages, land ownership, and work authorization in the Eternal City of Praxis. While evoking the same mythical supremacy as lost Atlantis – another technologically advanced and powerful civilization, according to the fiction – images of coats of arms and memes featuring ancient Roman busts constitute a tried-and-tested way of turning governance into a lifestyle brand hyper-optimized for twenty-something tech nerds on a high-speed diet of Dark Enlightenment texts and soylent. Still, it’s unclear if and when an IRL space will actually be established – self-pro- claimed Praxians mostly gather in groups chats on Discord, Telegram, and Signal.

They do come together, however. On several occasions, the company has even staged elaborate candlelit soirees in Manhattan loft spaces that are attended by an awkward mix of crypto nerds, Dimes Square regulars, and the founding father of neo-reactionary politics, Curtis Yarvin. In his writings, Yarvin references the need for a CEO monarch, an “American Caesar,” who would run the country from the top down, like a dictator. Yarvin’s justification for this choice stems from capitalism’s failures and the lack of inno- vation in government, but his reasoning is shaky at best – a disorientating mix of oversimplification and presenting fiction as fact. Nevertheless, it sparked Brown’s personal philosophy of “national accelerationism” and highlights a persistent idea among the internet’s crypto elite: that the West has fallen and that the only way to restore it to its former glory is to go back to a form of feudalistic rule – or worse.

The most tangible example of a network state, however, is Prospera, a Randian-style start-up city located off the coast of Honduras and backed by Silicon Valley billionaires Peter Thiel and Sam Altman. In Prospera, Silicon Valley billionaires, biohackers, entrepreneurs, and libertarians can escape government oversight and taxation to experiment with genetically modified bacteria and implant Tesla keys into their hands. Offering a libertarian fantasy of unbridled economic freedom, this special economic zone covers a square mile of the island Roatán and is the brainchild of Venezuelan-born wealth fund manager Erick Brimen. Unlike other IRL special economic zones such as Hong Kong or Shenzhen, Prospera functions as its own independent entity and is not bound by national or regional laws, meaning it pays no taxes to Honduras or Roatán despite an ongoing legal dispute with the local government. Given that the mayor of Roatán has spoken out about negative impact on the community, what is positioned as a start- up of the future feels uncannily like a repackaged version of colonialism – made all the more apparent when you consider that Balaji Srinivasan, author of the book The Network State (2022), explicitly mentions Israel as a guiding inspiration for his original thesis of a digital-first, community-driven attempt at building a new country.

Although many in the broligarchy – those tech optimists and medieval shitposters who value peak libertarianism – are dreaming up an alternative form of governance outside the modern Western state, some are hoping to create such a thing within it. The technofeudal lords Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, and Bill Gates all pledged allegiance to Donald Trump, who, within two months of returning to the presidency, is in talks to build so-called “freedom cities,” exempt from taxes and regulations across the US. If this were to happen, it might provide the legislatory infrastructure for many of these network states.

There are “many networks, many messiahs, many ideologies, all with their own Prophet Motives,” noted Alsindi in his talk “The Chain Male Gaze” at the 2024 Web3 Summit in Berlin. And in this free market of ideologies, it’s understandable why some might feel the allure of an “empire of so-called meaning in an age of chaos,” as per a Praxis social post on X. As Brown puts it, “Heroism is a key tenet of Praxis’s culture.” The word “hero” is an important keyword. Ursula K. Le Guin unpacked the term in her formative essay “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” where she outlined the hero’s “imperial nature and uncontrollable impulse, to take everything over and run it while making stern decrees and laws to control his uncontrollable impulse to kill it.” Although their aims to have dominion over the sea and outer space, arguably the hottest new corporate domains ripe for exploration (and exploitation), are definitely in line with Le Guin’s analysis of the hero, the network states and their Exitcore proposition are not very radical when you consider the infinite potential for worldbuilding that technologies like AI could offer a select group of techno-optimists whose state models are built on these emerging technologies. As Le Guin concludes,

“If science fiction is the mythology of modern technology, then its myth is tragic.”

Knightcore Kingdom by Cassidy George

When medieval covers of radio hits and PLAGUE DOCTOR MEMES started trending

during the Covid-19 pandemic, they felt obvious, even natural. As we plunged into the chaos of our own Black Death, many looked to the past to help make sense of the present – as an informative resource, an avenue for humor, or a means of escape. Anyone who might have dismissed

the sudden popularity of medieval things and themes as just another pandemic-era trend (baking banana bread, knitting) has been proven wrong over the past half decade. Our plague eventually faded into the background of 21st-century life, but the Dark Ages moved further into the cultural foreground.

The “knightcore” fashion trend that Balenciaga helped ignite with its AW-21 collection has rippled through luxury and commercial sectors, inspiring similar campaigns by Loewe and Burberry. Medieval looks have appeared on runways, album covers, and major stages – such as the Video Music Awards, where Chappell Roan performed as Joan of Arc earlier this year. Oversized sleeves, bonnets, ribbons, corsets, and bloomers are incorporated into contemporary dress so often that they have begun to lose their historical undertones.

Since 2020, an increasingly large subset of designers is moving away

from sleekness and precision, and back toward old-fashioned craftsmanship. An uptick in more rustic and brutal spaces and objects led Architectural Digest, in 2022, to coin the phrase “Middle Ages Modern,” which has been bolstered by countless smaller trend reports about such things as medieval tapestries and chain mail accents in interiors. This shift is also visible in the world of graphic design, where such fonts as Blackletter, Future Medieval, and Clavichord have undergone increased use.

Many of the best-selling video games on the market – Elden Ring, Hogwarts Legacy, Kingdom Come: Deliverance II – either take place during the Middle Ages or incorporate medieval imagery and tropes into their open-world design. “Culturally, we are empowering narratives of heroes and saviors,” said Sarah Rozansky, head creative at the research-based retail consultancy Doneger | TOBE. “Reframing struggles in this context enhances a sense of purpose and resilience,” she added. The hero’s journey archetype has even trickled into our language. Particularly among Gen Z, the phrase “side quest” is used in slang, and “lore” has almost entirely replaced the word “story” in discussions of an individual’s past.

Trump tapped into this spirit politically in 2021 by motivating disgruntled serfs to storm the United States capitol like angry peasants with pitchforks. Figures such as Andrew Tate socially harness this spirit by claiming to provide barbaric conceptual aids for generational crises. As algorithms breed further extremism, cancel culture unfolds in society like a modern-day Inquisition. Access to infinite information has had an inverse effect, leading to the devaluation of facts, sense, and logic, and an overall increase in ideological dogmatism. With two major wars in progress, a rise in populism and political violence in Europe, and America in the throes of a tyrannical regime, it is fair to say that we also are living through times of brutality and conquest. “The medieval period is associated with societal upheaval, plague, and feudal power structures,” Rozansky said. “This resonance isn’t lost in today’s climate.”

With this level of synchronicity unfolding across culture and politics, we are doing more than simply “looking back” at the

Dark Ages. We have welcomed their second coming.

A little bit about David Carson, the designer of the dossier.

David Carson (born 1955) was a professional surfer and teacher before he attended a graphic design workshop at the age of 26. Although it was intended for high school seniors, this two-week foray into design changed the course of his life. Now one of the most Googled graphic designers in the world, Carson is widely recognized as the foremost pioneer of the grunge aesthetic.

Carson has been entrenched in alternative culture from the start of his design career, working at Transworld Skateboarding (he was offered the job by Z-Boy Stacy Peralta) and Beach Culture in the 1990s, before being named art director at Ray Gun—a publication that Wayne Coyne of The Flaming Lips called the “most feared, the most radical, and the most confusing” music publication of the era.

Harnessing the power of emerging digital tools, Carson became well known for his somewhat diabolical design choices and his general disregard for legibility. (The most infamous of these decisions was printing an interview with the musician Bryan Ferry in the symbol font, Zapf Dingbats.) “The writers and musicians would be holding their breath, waiting for the issue to come out, not knowing whether their words, interviews, or pictures would be upside-down or completely hanging off the page,” Ray Gun editor Randy Bookasta said of Carson’s work.

After his stint at Ray Gun, Carson formed his own agency and worked with clients such as Nike, Pepsi, Ray-Ban, and Levi’s, and published several books, including The End of Print: The Graphic Design of David Carson, 2nd Sight, Trek, and Fotografiks. Although controversial at the time, Carson’s unhinged and anarchistic aesthetic epitomized the ‘90s avant-garde, and became an era-defining design language that is still imitated around the world today.

Buy the issue here

Credits

- America Is as Strong as Ever - Just Not as a State: Dr. Jens Hillebrand Pohl

- Interview Cedric Durand: Shane Anderson

- "Chain Male Gaze": Günseli Yalcinkaya

- Knightcore Kingdom: Cassidy George