Aries Aries Rising HOOD BY AIR

|Emily Segal

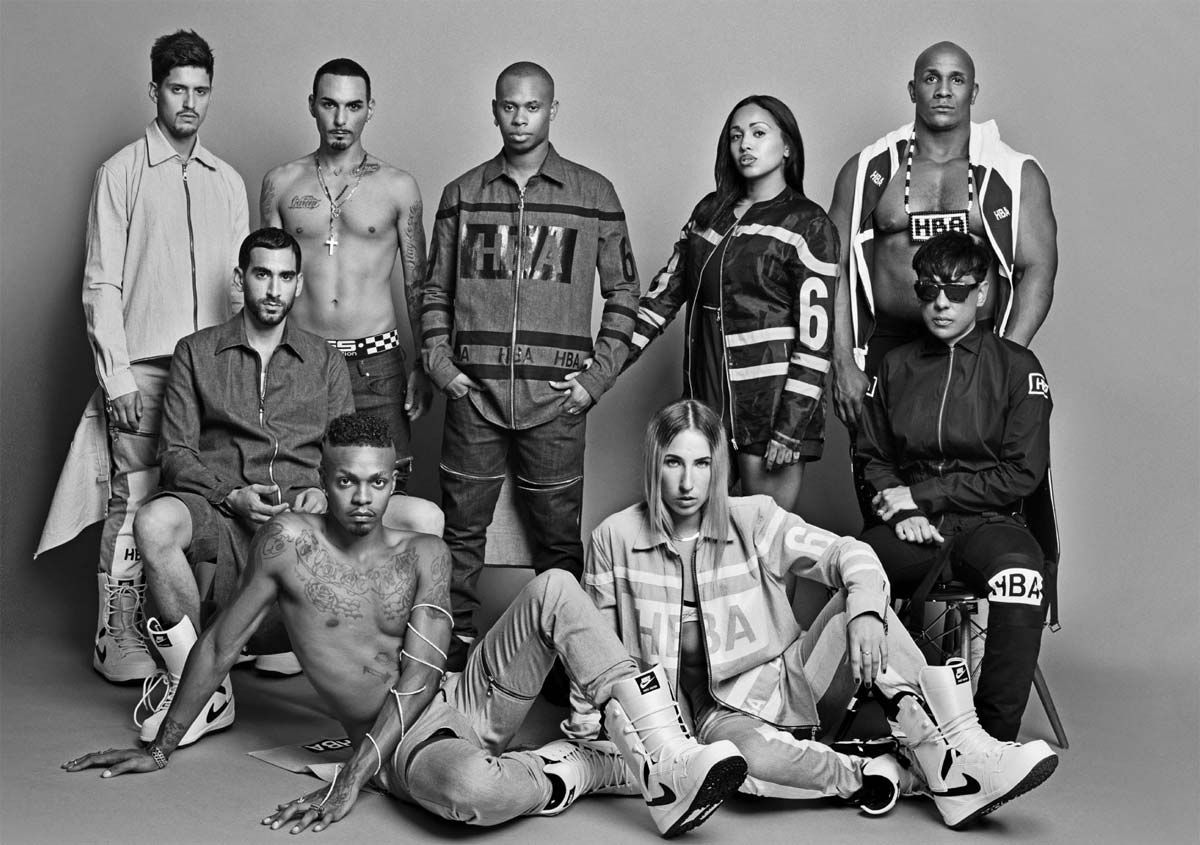

HOOD BY AIR is a phenomenon. The NYC-based label is run by Shayne Oliver, a 26-year-old designer from East New York, Brooklyn. In 2006, at 18, Oliver and friend Raul Lopez started Hood by Air as a T-shirt line that exaggerated the graphic and fit of 1990s streetwear brands like FUBU, Enyce, and Eckō.

The name, Oliver says, plays on “being from the hood, but taking the train downtown to hang out with skaters and artists.” Since then, HBA has become one of the most original forces in fashion: in March, the label was nominated for the LVMH Young Fashion Designer Prize.

Its cut-and-sew collections are authoritative and technically complex, challenging traditional categorizations of streetwear and luxury. But HBA is about more than the clothes: it is fueled by an entourage of close collaborators and friends in the art, music, and party worlds.

“We’re trained in many different languages,” says Leilah Weinraub, HBA’s director of art and commerce. “Queer culture. Black culture. Whatever. Maybe people need a point of entry.” With momentumthat has little to do with business and everything to do with culture, HBA is making the fashion establishment go haywire.

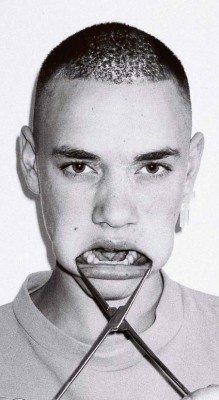

The best way to understand Oliver’s strategy as a designer is to see it as a reflection of his strategy as a DJ. His description of his direction for GHE20G0TH1K, the party he co-ran with DJ Venus X and producer Physical Therapy, could double as a description for his fashion brand. “It was a bubbling reference board type thing. It had to do with being noisy, it had to do with being funny, it had to do with being an asshole, and loving the people you’re around too. It was all of that. People really loving the song and turning it off because you like it too much and you change it to something else and they’re like, ‘Ugh, okay.’ It’s like, I don’t know, you know that sexual term ‘edging’?”

Hood by Air is both a success story of an underground NYC label scaling up – in the form of an iconic street and high-fashion brand – and a cipher for a whole new category of casual, logo-maniac, black and white “fuccboi” fashion. There are few contemporary brands as relentlessly knocked off, copied, and versioned.

Hood by Air is famous for its logo: a bold “HBA,” all caps, white on black, or black on white. There is something confusingly legible about a logo being cool. Liking a logo is very literal. Shayne explains the first music he played at GHE20G0TH1K: “I was playing acid house and I was also playing, minimal darkwave just because I was thinking very literally about the name.”

What makes HBA radical is the way it takes fashion at face value. Whereas the ghetto goth look is about mixing elements of what’s traditionally considered “black” and “white,” Hood by Air makes clothes that are literally black and white. Rei Kawakubo has remarked that she believes the avant-garde is a cliché; one could argue that Hood by Air’s pan-alternative aesthetic is a recognition of this having been true for a long time. Describing the backstory for HBA’s famous logo, Shayne says, “Well, deconstructionism had become a sort of logo to me.”

So why not just put a real logo there? “We knew that being overtly punk didn’t even resonate as anything that was edgy or had shock-value because it’s like, punk, we get it, you know?”

In this post-transgressive zone, the logo has become an anchor or MacGuffin for pulling the brand’s customers onto the next thing, the next look. “Well, it’s just like moving the logo from a T-shirt and putting it on this really insane thing that you wouldn’t wear at the time. It’s like, ‘If you wanna wear the logo you have to put this on’ type thing. Sneaking styles into other styles. Like putting denim panties inside of a jean and then being like, ‘Well this is a jean, so what?’”

It’s wrong to see this as a trick; it’s more like good parenting. “The only thing I want from my customers is for them to trust me. Like, I got you. I’m never gonna have you looking like a fool, but I do want you to step it up.”

“It would be wrong to reduce Hood by Air to an oversize T-shirt and track pant,” explains Mark Holgate, fashion news director of Vogue. “Shayne pushes things with construction and proportion in quite a sophisticated way. And it’s not like they have the endless technical resources of an established fashion house. Hood by Air is the expression of a generation that sees fashion as part of a broader creative endeavor – whether it’s clothes, a club night, music, photography, whatever. HBA comes fully formed in a way that suggests a new model. It presents a range of beauty both male and female, and others who might not readily identify as male or female. At the same time, they understand the spectacle and thrill of fashion. The voguing finale of the last show, the “10,000 Screaming Faggots” soundtrack by Total Freedom – that was amazing.”

Hood by Air emanates a friendship energy. It radiates networks of personal and professional friendships, and provokes the anxiety of contemporary friendships, too. There’s an element of HBA that stresses people out, and I think it’s the question of whether it belongs to them, or even if fashion can properly belong to anyone anymore. “I’m basically who I’m making it for, myself,” Shayne explains. “Friends too, but then you learn the customer and they become friends you don’t wanna be late for, like, ‘Damn I need to be on time.’”

Shayne will let you have your cake, but he’ll make you eat it, too. This is ultimately what makes HBA non-cynical and potentially a truly contemporary luxury brand – one that insists on the sincerity of fashion itself. There is no punchline here.

EMILY SEGAL: I’m interested in you telling the story of the G H E20G0TH1K party and HBA’s trajectory – how they overlap and what they mean to each other.

SHAYNE OLIVER: I’m not really a DJ. I just meld and mend songs together in this patchwork-y way. It was like a new sound in general. We all started playing like that together and along came a mashup type of thing. It was very progressive in a way. It was also just a thing where it was actually for our friends and the reaction we were getting from our friends and how they were enjoying themselves. That energy became the guidelines of what they were creating. I was always, like, searching. At the time, GG was a passion project, so it was like I was constantly looking for things that spoke to me the most, and I felt that if it gagged me, it was gonna gag my friends.

How did you do that?

I mean, I don’t know, just by incorporating crazy things like, “Oh, it’s about Cruel Intentions.” It’s about things I thought were important to this angsty energy. It’s just how I make stuff. It wasn’t actually big – it was sort of obscure but very much had a pop edge to it. It was about figuring out how to bring it back home – these are the hits, this is what resonates as a good song to party to. It was cultural creative direction: let’s do Katy Perry hardstyle, let’s get into vocaloid.

How did you get over the hump with Hood By Air?

I guess through DJing I was able to save money, and then eventually I was just hunting around with the production houses and creating pieces from what I could afford. I was like, “Lemme make this next month, lemme make this next month, and then maybe I’ll have, like, eight pieces, and I’ll make a bunch of T-shirts to fill it in.” So really the T-shirts were a secondary thing. It was more the kind of – not fluff, but it made the look work together. There were main pieces that were more conceptual things.

Do you have favorites? Like darlings from that time?

Yeah, there’s this one jacket that I still have that’s a mix between Chun-Li’s outfit in Street Fighter, a trench coat of a business man, and the skirt and the top of a secretary’s outfit.

There were times when I felt really discouraged and really betrayed, and it almost made me want to succeed. I was like, “Fuck you, fuck it.” I’m not gonna do anything and not have it be as strong as possible, so it became like a power thing. HBA is a powerful thing. It always has been about these power pieces, but it became about a philosophy behind the brand even more. It’s a T-shirt and it’s serious. I think people started feeling that too.

You’ve mentioned the significance of diffusion lines to Hood by Air. What was appealing about that to you?

I was interested in how to incorporate logos – not in streetwear, but with actual street brands. How CK Jeans was at one point like Pepe. Pepe’s a really important one. Polo Sport. We were just talking about that classic bag – how that was the bomb. And Macy’s fashion – which is really important. I grew up in the age of diffusion brands and of bringing main collections down to the street level and [also] brands that were doing the opposite of that, being like, “We’re fancy, look at how much we can do that.” That element of nouveau-riche street stuff.

It had to do with being utilitarian. It had these things that were meant to actually be active, which I think related to the city a lot. You had kids who didn’t wanna look like assholes walking around in preppy looks and being in the city. It was like Polo Sport having that feel, but with the added dimension of the Polo stuff, so you had that feel of being rich while looking active. Columbia, North Face, all that was there too.

That resonates a lot with our current moment, I think.

These brands are bringing it back, and, like, DKNY is cool, but I think they’re referencing the wrong era. What I’m thinking about is when it was, like, cyber-DKNY, and Brandy was wearing DKNY. And Spice Girls fashion and Buffy. It was happening, it was going somewhere. A Y2K look. That’s what it was. I don’t know if we’re supposed to be talking about an era here. Even Tommy was getting into that, too. Guys were getting way more tech-y – tech fabric and suedes and denim, and that’s all in one outfit. That was really good. You have an outfit, and it’s like, “What is this?” And the foundations have nothing to do with each other. That’s really important, for sure.

There are these moments where everyone wants to look really water-resistant. Why is that? Obviously part of it is some fashion cycle, but part is because of other cultural factors.

It’s so true, though – that look is so important. The amount of times I run back to North Face Steep Tech jackets – that reference is crazy.

So what does North Face mean to you? Why are those jackets so appealing?

It was like – one, it was kinda baller status, like, “Oh, no bull, my jacket is $600. I’m so warm, you look kinda cold.” It was that. “Boo, I’m really warm” – it had that aspect, and it was also the price – it was luxury. Then, they came in a crazy amount of colors. Full colors came out each season, and it was a “Who’s gonna get what color? Who’s gonna put that color with that sneaker?” type thing.

Were you into sneakers?

I was. I’ve been around with sneakers. I was already playing around with designs and designer footwear. I would want an outerwear piece, and it was North Face, and then I’d get into these, like, nasty Italian shoes I have. So there’s a lot of that happening in my personal self. While I was observing, I was going through all this North Face stuff and really deep in it – even just being an admirer of men, I had an outsider view of this whole thing. At that time I was also beginning to float more into educating myself on that stuff and hanging out at Club Love around 2000/2001, and that hanging out kind of led me into really actually learning about what was going on in that scene – wanting to know and seeing the face value of it, the fashion side of it, being mesmerized and thinking, “Oh, this is really cool.” It was better that I did it when I was really young, cause I got it.

How do you filter yourself?

The lifestyle I grew up in – living in Brooklyn and in New York, [I would have] to incorporate how to get from point A to B without being killed. So it’s not necessarily like I was dumbing down the look, but I would signal certain concepts to people so they would react in a positive sense, think, “Oh my God, these are really cool.” It would be like wearing Uptown things with an assless bodysuit. Like here’s an Uptown, but he’s crazy.

Do you ever feel like the HBA T-shirts are too big of a deal?

Yeah. I mean, I’m trying to figure out a way of pushing people more, which is why this season I did newer T-shirt shapes and next season I’m gonna evolve with that concept even more. If you want a T-shirt, I’m gonna make you wear, like, the most insane T-shirt, but also something that people would feel comfortable with. That’s also a thing I’ve always been into: creating new classics for people. The reason why the classics collection was created in the first place was so we could have these things that people feel comfortable in, but each season would have a new piece from each collection that people respond to in a higher way, so people can think it’s normal and move on.

In 2014, what does luxury mean? What is luxury about?

I think what luxury is now is like an idea. Half idea and half fabrication – it’s both. It’s an idea and actually feels good when you have it on. I also feel like there’s luxury when you have on a baggy T-shirt because you feel great in it. If you feel really good in something, you should pay for it. People sometimes actually don’t know what’s gonna feel good, and it’s like, “Okay, that’s why this T-shirt is $500.” Because people don’t remember – in fashion they don’t remember how good it feels to be in a T-shirt because they’re so caught up in what’s happening in the moment. It goes in waves. That’s just what I feel like people need to understand, and I feel like that’s what’s happening in our generation. These are jeans, and you say that isn’t fashion, but you wear them a lot. It’s pushing it on you as a concept: you’re gonna wear this jean, and it’s not gonna be, like, a Gucci excessive jean. It’s gonna be a jean that looks like a jean that you should wear like a jean, and they’re gonna buy it as a jean.

How do you think about price?

I think you should pay for what you’re passionate about. You know what I mean? If you’re passionate about the idea, then pay for it. I don’t think it’s about gypping anyone – I think people do that. People log on to trends and work people out for everything they’re worth. I think that if a piece is really important, you should pay for it. It’s not about upper class or lower class. It’s just about you really being obsessed with that idea and investing in it.

What does the term “fuccboi” mean to you?

I feel like it’s the same as any racial slur or “faggot” or whatever. I don’t know what they’re talking about because I guess it’s in the world of boys who are pushing, who see stuff and they don’t know what they’re wearing, you know what I mean? I get that too. I’m like, “Oh, I can see that happening, turning into a fuccboi.” But when people take the origins of it, I’m like, “Okay, if you’re gonna call me a fuccboi, I’m gonna own it. And spit it back in your face. I’ve never had the contempt to be like, “Whatever,” because I want my friends to look like fuccbois and look great. Look really good. It’s like the Instagram thing, people taking something totally out of context, because it’s more of the thing they see, like Kanye, and they don’t care about the brand. You have to be smart to be attractive. I think that something is cool because it kind of allows people to dream and push for their goals. Some people just don’t get it fully. And those to me are fuccbois.

Fashion victim, hypebeast, fuccboi. I’m interested in whatever that X-factor comes in to – because there’s good senselessness too. But maybe this is the bad senselessness or something?

You call them “headless,” so I guess that “fuccboi” or whatever would be headless. It’s good and bad, you know? Headless is like you thinking you have no thought process to what you’re doing. You’re either doing it without thinking or it’s intuitive. Or you know it and just do it anyway. Having no thought process to what you’re doing and either doing it without thinking or knowing it and just doing it anyway – just be headless like, “This looks really bad, but I’m just gonna wear it anyways.” That’s somebody who knows what they’re doing with something bad.

So what are your ambitions? Where is this thing in 20 years? Where are you?

I think HBA is like a house of commentary that has a viewpoint. I wanna make actual physical spaces and figure out more how to blend the different worlds and realities. It’s funny how kids are around each other. It’s weird how technology is acting as our subconscious. It’s about figuring out how to relate that to the actual adult world. That stuff interests me. Having a school of HBA and constantly teaching people what’s on in this world. I’m always about listening to what makes me feel like I’m old. I never question. I always think kids got it going on. You know they’re the ones affected by it, so they know. Cause even if it’s hyperreal or it’s fake, that means the world is becoming fake. We should all pay attention to what they’re saying.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZkqVIlqpC3Q&feature=youtu.be

Credits

- Interview: Emily Segal