Instagram Co-Inventor MIKE KRIEGER Speaks with HANS ULRICH OBRIST

Founded by MIKE KRIEGER (Technical Lead) and KEVIN SYSTROM (CEO), Instagram launched in 2010. The mobile app grew to over 100 million users by 2012, when it was acquired by Facebook for a reported one billion US Dollars. It now has over 300 million users and publishes 70 million images per day. Instagram disrupts every visual industry.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST speaks with Mike Krieger, one of the two most influential men in fashion (and soon in art, too)

What’s the first image that was ever posted on Instagram?

My co-founder, Kevin Systrom, had just come back from Mexico, and he posted a photo of a very small dog that he had seen there.

And what is the first image you ever posted on Instagram?

My first one was out the window of the warehouse that we were working in. We were right on the water, the sky was really blue. I like that photo, because it was the view I had for much of the year when Instagram was working out of this big warehouse. Everything looked beautiful outside, but we were inside working really hard.

What’s the most recent thing you posted on Instagram?

I hate to admit it, but it’s a picture of my dog.

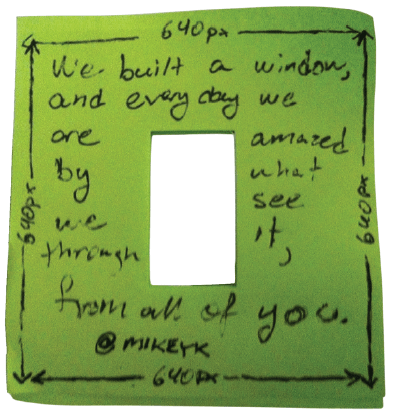

When we met for the first time, you participated in my Instagram project, where I post handwritten sentences as a protest against the disappearance of handwriting. You drew this wonderful post-it about Instagram being a “window.” How did that come to mind?

Instagram is about being open and not prescriptive. For us, the fact that you can have a project that is taking photos of post-it notes and thinking about handwriting, there’s nothing in the product that says, “Oh, maybe you should do this,” but there’s also nothing in the product that says, “You shouldn’t do this.” While designing products, I think that’s very important. You have to have enough constraints to have the right creative stories come out, and also enough constraints so that there’s some rules in place. We give people a square inside which they can be creative. We don’t impose restrictions, and instead we say, “Do what you can with this, and if it’s interesting, you’ll find an audience.”

You studied a combination of linguistics, philosophy, coding, and psychology at Stanford. So it’s interesting that you invented a platform that brings so many disciplines together. How did all of those fields of study come together for you in the invention of Instagram?

I think the one thing that makes Kevin and myself unique as co-founders is that we didn’t come at this from a technology angle. I think what people loved about Instagram from the very beginning was that they could tell there was a real soul to it. And I think that came from having an inter-disciplinary background and having not just studied coding. I loved studying everything from philosophy of mind, to Russian literature, to graphic novels. Nowadays, I feel like my way of learning is through Instagram. I follow accounts that will teach me something about the world.

You’re also a collector of art, so I’m interested to hear about your relationship to art. One can observe more and more that Instagram is now an exhibition space. Artists such as Frances Stark not only have great Instagram accounts, their Instagram is an artwork itself. One now sees Instagram elements framed in gallery and museum exhibitions. What do you think of this?

What I love is that it’s deepened my connection to art over the last couple of years. Art is often the reason that I travel somewhere. When I’m in Mexico City, I’m all about understanding what’s going on in the art scene there. There’s just no better way of understanding a city and a culture than through the contemporary art that’s being created. For me, it’s interesting to see what an artist’s worldview is through Instagram. With my collecting, I’m very interested in ways of playing with medium to mess with your usual expectations. For example, one sculptor that I really love is Ricky Swallow, and he posts quite often on Instagram. So I understand his sculpture and his way of seeing far more now, because I get to see how he interacts with the world. Or Stephen Shore – who’s a wonderful photographer – is in some ways the original Instagrammer, in terms of how he captured the urban landscape as it expanded. Seeing him on Instagram is such a revelation, because you can see that even though we’re giving him a small window on the iPhone, he’s still Stephen Shore.

Tell me more about your work as a collector.

It occupies a lot of my brain. My fiancé Kaitlyn and I are new collectors, but we’re trying to approach it very intentionally and learn as much as we can about contemporary art. It’s important for us to not get too caught up in what can be very market-based in art, and really focus on the things that move us. And in having those conversations about those ideas, we feel very nourished and fulfilled. We travel to see art a lot. We’re going to frieze, and we’ll be in Basel in June, and I always look forward not just to seeing the art, but also to hearing more from the people around it. In San Francisco – getting to know the gallerists here and meeting some of the artists – it feels like home already, even though we have not been collecting for very long.

Art now also appears in Instagram through the selfie. DIS, the artist collective that is curating the next Berlin Biennale, did a book called #ArtSelfie published by Jean Boîte Éditions. Is the selfie ruining the world or saving it?

Oh, man. I first experienced the “art selfie” in Mexico City. There was a woman walking around, and I offered to take her photo, but it was very important that she took her own photo. She didn’t want me to take it. And she would walk from piece to piece and take a photo of herself with the piece. It’s interesting. I think it’s something very human and very ancient. It’s a way of leaving your mark on these things, of understanding your own perspective in relation to the art. I draw the line at selfie sticks, though. I feel like they can be dangerous in a museum.

Instagram has become a platform for young artists to emerge. For example, we saw the work of Niko the Ikon for the first time on Instagram. Then Simon Castets and I started the 89plus project, making a cartography of this generation of artists born in 1989 or later. There are obviously several ways an artist can emerge, but it is actually quite recurrent that artists appear by using Instagram to gain initial visibility. Was that ever something you had envisioned?

We couldn’t have imagined that artists would be discovered through Instagram. As we think about the future, we have a certain focus – and this is pretty hard to do on Instagram – which is when you discover something great, let it be something you can tell other people about. So we’re doing a lot of thinking about this concept: If you found the next great artist, how to help you tell that story as well.

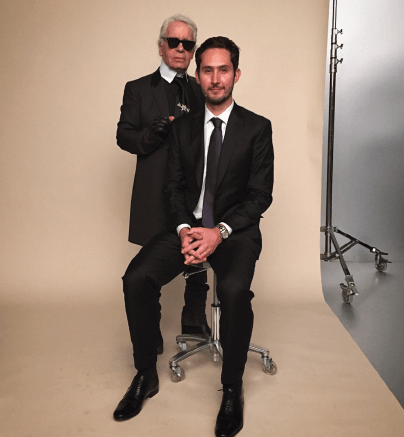

Tom Ford recently said that an Instagram post of Rihanna wearing his label is more relevant than any other coverage for his brand. And I recently saw that your co-founder Kevin Systrom made a public appearance with Karl Lagerfeld. What was it like watching this relationship between Instagram and fashion evolve?

It started very organically and came from a community that understood why Instagram might be helpful. The interesting thing is that Instagram is involved in every aspect of your life. So I think it shifts fashion from being this very detached, glossy, magazine experience. It becomes more lived-in. I love Karlie Kloss’s Instagram feed, and it ranges from her on the runway to also having a very normal moment. I think it connects to what people actually experience day-to-day, which is not the runway show. It’s just life, and life elevated.

“Life elevated.”

Instagram also empowers people who are not necessarily in the fashion world to be fashionable and tell that story. There’s a hashtag, #OOTD, which is Outfit of the Day, and if you go to #OOTD, it’s all about self-expression. I took this great design class when I was at Stanford, and on the first day, the professor asked people to raise their hands if they were designers. And then he said, “You put together your outfit this morning, you do it every day. You design your space and your work. Design is an intention, and everybody has to do it.” It’s true. Even if you’re doing things that are not design, you’re designing. So I think it’s important to have this egalitarian platform.

There’s a kind of beauty to the fact that it’s been used in all these ways that no one ever planned.

Every social product follows the laws of physics. That’s why one of our early choices was to make Instagram public by default. So if a new artist starts posting their work, and you happen to search or recommend it to somebody, you can have access to it. It sounds normal now to be public by default. But five or six years ago – when we were thinking about this – it was a scary notion to share photos with people who aren’t your friends. It opened up a whole new set of production. People began producing things that were meant to be shared.

What are some recent Instagram accounts that have surprised you?

There is one I found called @bladerunnerreality, where they take photos that feel like Blade Runner (1982) but exist in reality. It has a retro-futuristic feeling that is really wonderful. Another account I love is from Jordan Mechner. He made a great video game called Prince of Persia in the 80s, and he’s continued to write, make films, and sketch. I also love following galleries and frieze magazine, and flying around the world through that.

Last year, Instagram deleted many fake accounts. How did you separate the real users from the fake users? What is a “real” user?

This is a big part of the work we do – and the team has a great name. They’re called Site Integrity. It’s interesting, because you could say, “Well, I have an account for my dog. Is that a real user or a fake user?” We really think about intention and whether what they’re doing is posting content that is authentic and original. We have a lot of automated systems where, if we think you’re being spammy, we’ll investigate and we have lots of rules around that. So when we corrected the accounts last year, it was a lot about removing the accounts that we had found were being spammy and making sure they were off the platform.

Facebook and other platforms use massive amounts of advertising. And it’s kind of interesting to see how young people are very skeptical about platforms that use advertising. They like Instagram, because Instagram doesn’t have a lot of official advertisement in its stream. Is that part of the philosophy?

When we started advertising, we wanted to ask how we could make advertising feel great on Instagram. The adjective we use internally a lot is “Instagrammy.” To that end, we’ve started working with people who have a very natural affinity with Instagram. Mercedes-Benz produced an advertising campaign on Instagram that was very much about interacting with the community, and taking people who were famous on Instagram and having them be part of the work. It’s about the thoughtfulness and the craft. We have to be very open about what we’re doing, and be very receptive to feedback as well.

I’m very interested in the future of Instagram. Where do you see Instagram in five or ten years?

About 70 million photos go into Instagram per day. But right now, for any given day – even if you’re following a fair number of accounts – you’re generally seeing the same people every single time. What we want to do over the next few years is strand people’s vision of the world through Instagram. There are things happening all over the world that we cannot experience in person. Next week is frieze, and even if you’re not there, can you feel like you’re participating? Can you hear different takes on a particular topic? Can you travel around the world through Instagram and hear the stories that are being told in real time? We have years of work ahead of us, but this year we’re starting to make that more of a reality.

Do you have any dreams or un-realized projects? For you, or for Instagram?

I once told Kevin that we have to imagine the science fiction version of our product, and then try to understand what we need to build in order to eventually realize that science fiction. For me, it’s teleportation – being anywhere at any time and experiencing it. So we’ve built version 0.1 of the teleporter, and over time we’ll make it feel more and more like you’re actually there.

Interview by HANS ULRICH OBRIST