Three Month Fever: The Murder of GIANNI VERSACE

First published in 1999, Three Month Fever by Gary Indiana delves into the media’s hyper coverage of the man who killed Gianni Versace in 1997: Andrew Cunanan. Cunanan’s transformation from anodyne serial killer to a diabolical tabloid icon was fuelled by the frenzy of news sensationalism. In Three Month Fever, Indiana creates a compelling portrayal of a young man who graduated from pathological liar to murderer and took the lives of five men, including Versace, before taking his own life. Fiona Duncan reviews Three Month Fever, on the occasion of its recent republishing by Semiotexte.

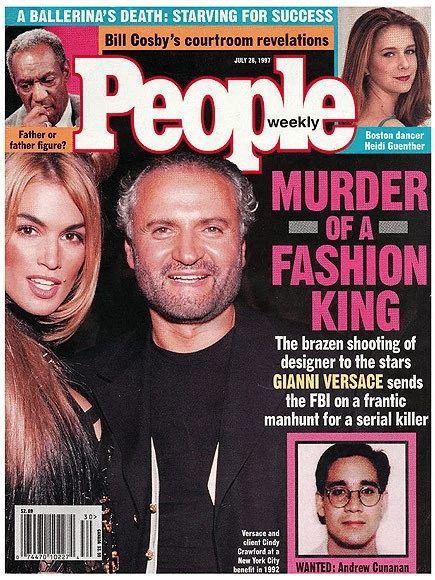

On July 24th 1997, Andrew Phillip Cunanan joined the 27 Club. It was hitting the hundreds with humidity that day in Miami, where Cunanan, an unemployed 27-year-old Filipino-Italian-American, had been squatting on a houseboat, wanted by the law. He’d killed five others by then, the most recent being famous—Italian fashion designer Gianni Versace—so now Cunanan was too. He was all over the news. 24-hour news. Cunanan’s case was ideal headline fodder: deviant sex, drugs, and celebrity, a cross-country manhunt. “There was this mania,” says Gary Indiana, author of Three Month Fever: The Andrew Cunanan Story, a 1999 novelistic nonfiction re-editioned this year by Semiotext(e). “One of the threads of the story after Andrew shot Versace and before he shot himself was, he could be anywhere. He could be in your neighborhood, he could be in your city…”

Security was tightened at fashion shows in New York. Cunanan was in Miami, though. In South Beach. Where Versace reportedly spent 32 million renovating two buildings on Ocean Drive, a green arterial road paralleling the beach. The Villa Casa Casuarina is now a boutique hotel. Gianni was shot before his door. Nine days later, about to be discovered, Andrew, assuring his motives remained a mystery, the ultimate story, shot himself in the right temple with the same Taurus PT100 semi-automatic pistol. He was one month shy of his 28th birthday (a Virgo).

20 years later, right now, Internet bylines are boasting A look back at the ‘Versace Murders’ / What You Need to Know About Gianni Versace’s Tragic Murder / Inside the mind of the serial killer who murdered Gianni Versace…

The feeling of most true crime drama—TV, movie, news—is salacious, malicious, pleasurable guilt, like gossip, car crashes, and pop pornography, thrusting to a predictable climax, that narrative drive: you can’t put it down or look away. Three Month Fever isn’t that. There’s a nauseating inanity to its crowded prose. The reality Indiana summons is one you can understand wanting to get the fuck out of. Childhood abuse, homophobia, self-loathing, superficial friendships, usurious affairs, boredom, phoneys, gluttony, rejection, projection, magazine reading, credit card bills, HIV/AIDS, and closets full of tangled lies and older more moneyed men. It’s an American reality—Cunanan’s everyday life. His father served in Vietnam. He abandoned the family to evade an embezzlement charge when Andrew was still a teen. The lifestyle magazines Andrew escaped into imaged success—the dream. America is fat with failure.

Stuffed with brand shorthand, kinky play roles, fashion, fame, and other surface cues, the Versace/Cunanan story is one that can write itself, which is dangerous. “Cunanan, who liked to wear Versace label underwear,” wrote Newsweek in 1997, “was a wanna-be in a wondrous kingdom of make-believe.” Doesn’t the author (Evan Thomas, who still works for Newsweek) sound like he’s having fun?

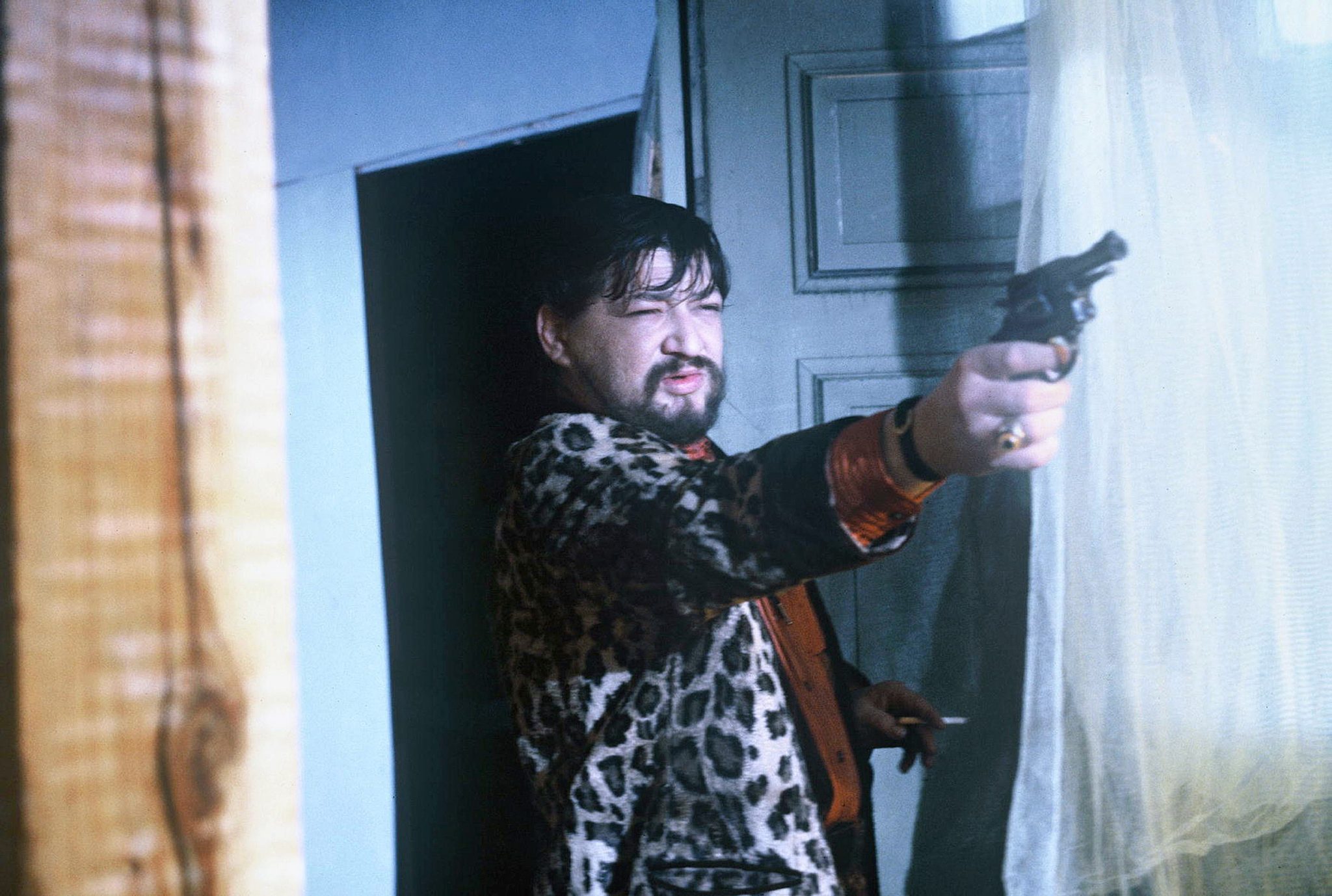

One reason Cunanan’s story writes itself is because he wrote it. He fashioned fabulous fictions, like false names (De Silva) and patrimony (rich Jewish), around him, “a liar.” Glamour. Gianni Versace traded in it. Inspired by street walkers and BDSM, Versace sold the look, “hooker haute couture,” of life like Cunanan lead to the high class he aspired to. Cunanan still doesn’t make the list—not like Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kurt Cobain, or Amy Winehouse, all of whom were, too, sexy, creative, damaged burn-outs. Cunanan wasn’t creative enough. He let his imagination be organized, like most Americans, by givens: commercial stories and products, status symbols. A true fashion victim.

Though Three Month Fever only side-mentions Versace (“Fashion, it’s just not my thing,” says Gary), there’s a glut of coverage on his side of the story, including a made-for-TV biopic starring Gina Gershon as his sister Donatella and a forthcoming American Crime Story with Penelope Cruz playing her. Consuming this stuff is part of the fun and tragedy of reading Three Month Fever. It’s obvious how the powers-that-be—here: the Versace dynasty—got to control their narrative.

“Part of what bothered me about the whole business,” Indiana explains; what compelled him to write what he did, “was that Andrew killed all these other people who apparently didn’t exist as people in people’s minds—” their deaths, which preceded Versace’s, maybe got a small column mention in a few newspapers. Minneapolitan propane salesman Jeffrey Trail, architect David Madson, real estate developer Lee Miglin, and cemetery caretaker William Reese— “they were just undifferentiated victims, and they were more interesting to me than Versace.”

Compassionately storying otherwise neglected lives, Three Month Fever balances out mass media bullshit with vengefully intelligent execution and art (the heavy beat of broken bleeding heart). It reads rivalrous. Better researching a well-rehearsed sensation. “I went pretty much everywhere the story took place,” Indiana told me. “San Diego, Minneapolis, Florida, the war cemetery where Andrew shot the caretaker [Pennsville, New Jersey].” Indiana spoke with coroners, police officers, reporters, and people who knew Andrew. This first-hand research is folded in—“a pastiche,” the author calls it—with RL media lines, police and FBI documents, some writing penned by Cunanan, and a lot of evident creative freedom. Indiana made up dreams, fantasies, actions, and desires for his characters, narrating unverifiables, like: “Immediately after killing Jeff,” he writes, “Andrew slipped on the Ferragamo loafers he’d taken off earlier, in order not to track blood all over the house, then set about mopping up the mess he’d made everywhere, governed by a ridiculous impulse to hide everything before David returned from walking the dog.” Such creative liberty is unlike that spelled by the likes of nineties Newsweek only in that it’s realistic, and so, in a way, less believable.