For TOM SACHS, Money is No Object

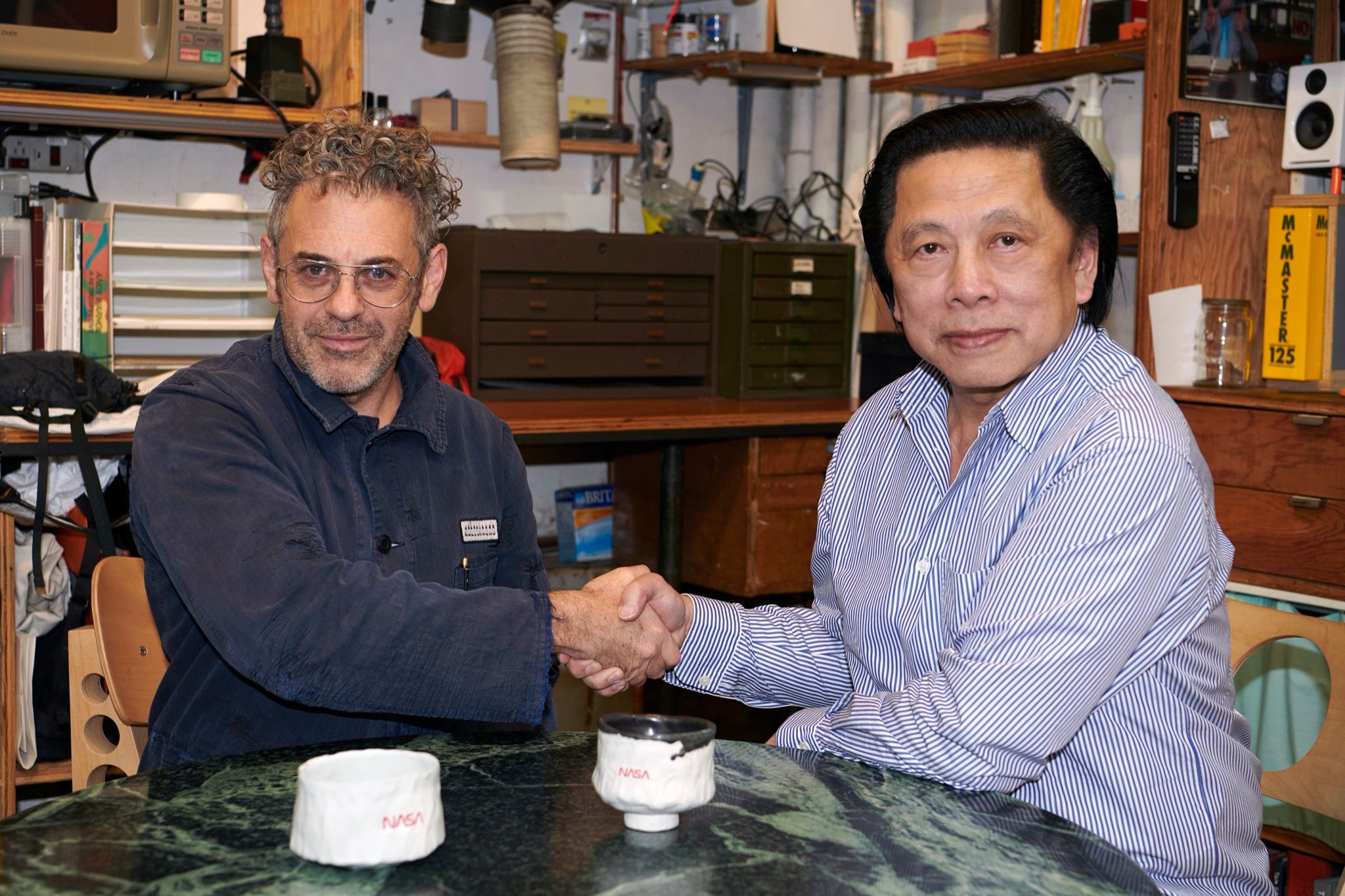

|John C Jay

For Tom Sachs, commerce doesn’t compromise art’s integrity. To the contrary, it helps democratize it: when someone sees a Tom Sachs × Nike shoe, they are not just exposed to his practice but incorporated into his “team.” A sneaker and a sculpture are both art, and art is all about delivering authenticity – a vehicle to help you down the path of crafting your own rules for living. Sachs idolizes Joseph Beuys and Isamu Noguchi, two artists who both produced commercial products alongside so-called fine art. He detests obfuscating art world types and gate-keeping academics. And while his artworks often fetch six digits at auction and his sneakers sell for upwards of €5,000, Sachs asserts that price is inversely proportional to importance.

In short, Sachs’ practice is all about its own economy – not only of capital but also of authenticity, truth, meaning. A dizzying array of symbols of late-capitalist modernity – Hello Kitty figurines, NASA space shuttles, the twin towers of the World Trade Center – serves as his source material, as complex and confounding as the thinking behind the work. Bricolage is Sachs’ privileged technique for navigating it all. The Chanel double C is emblazoned on a guillotine; the Hermès horse and carriage is superimposed on a McDonald’s burger wrapper. Paradoxes abound but, then again, the same is true of economics more broadly. At once unflinchingly realistic and naively optimistic, Sachs appears to be both product and producer of the complexities of the art world in the post-truth, post-neoliberal, post-everything era. We paired Sachs with the artist with John C Jay, currently the president of global creative at Fast Retailing, whose subsidiaries include Uniqlo, Helmut Lang, and Theory. Old friends, they cover significant ground, from Sachs’ recent interest in “the Christ myth” to his tips for emerging artists.

John C Jay: Why do we need art today?

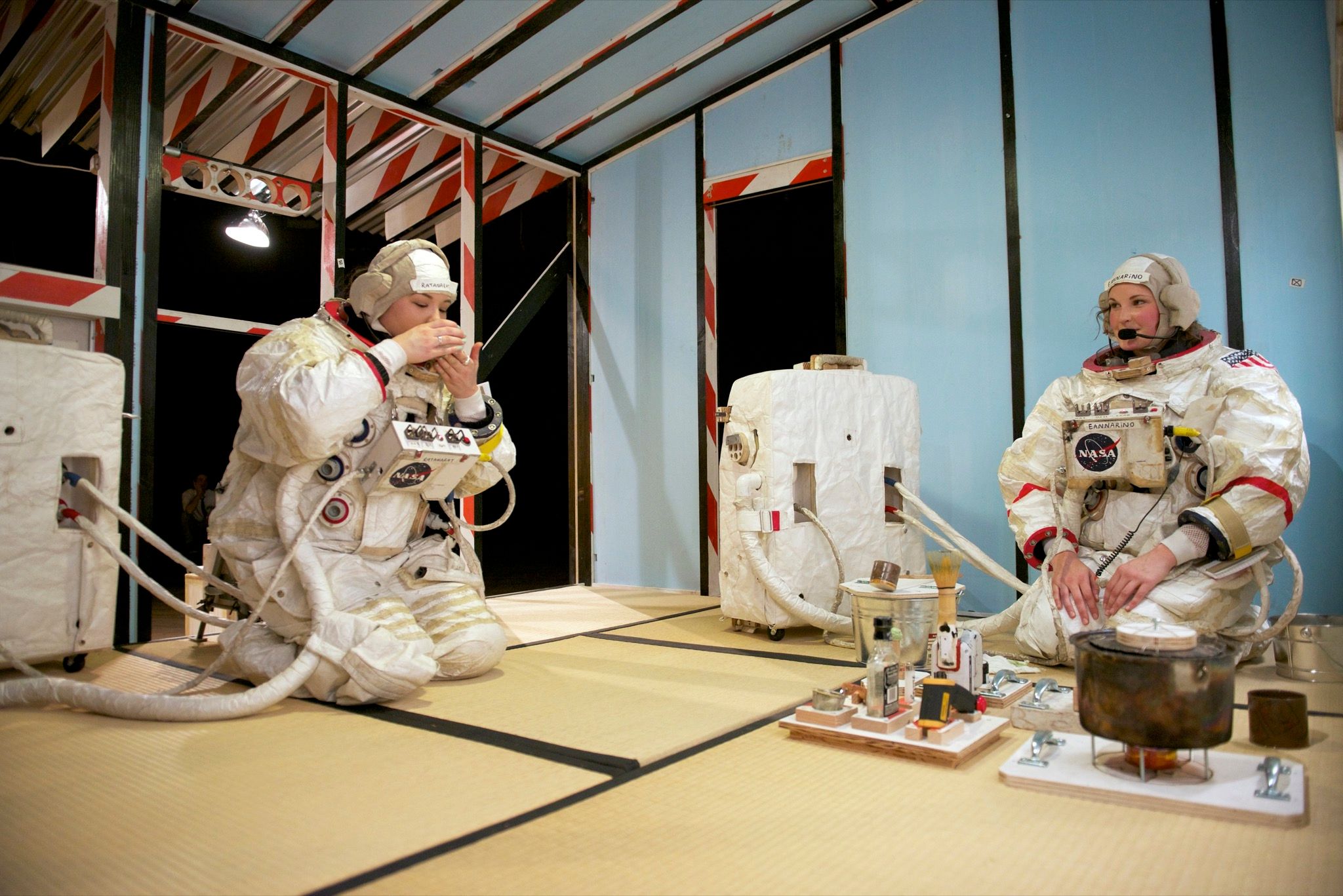

Tom Sachs: We don’t have rituals anymore – they have been replaced by sports and shopping. The art that we make here in the studio is a ritual – the process is a ritual, and the work itself is a ritual. We are in the business of creating rituals that are meaningful to us. Our Space Program is real – we really go to Mars and Europa and other worlds through the work. Sure, our spaceships are made out of cardboard and duct tape instead of titanium and kerosene, but we realize details to such an extreme degree that, for us, the work be comes real. So, when we do one of our live demonstrations, we don’t ever use the word “performance.” In fact, we have a swear jar and you have to put in one euro if you say “performance.” It’s demonstration. We also don’t say “fake.” We say “our NASA” versus “the other NASA,” because by realizing those details to an extreme degree we create authenticity. I think, to answer your question finally, the thing that we are always looking for in art is authenticity. That’s the holy grail in all art, whether it’s painting, sculpture, or commercial art. We are always trying to deliver authenticity.

You may have answered my next question already, but is art necessary?

It’s like [Abraham] Maslow’s hierarchy of needs – it’s always at the bottom. I think oxygen, food, sex, and water are up there, and then way, way at the bottom there are needs like love and art. But they are, in a way, the most important, the highest calling. When I go to psychotherapy, I’m working on refinement issues. I figured out how to get through the day without killing anybody, which I achieve most of the time, and I’m working on increasing my performance as a human being in this life. And by performance, I mean all the important stuff like Christ’s message of helping others and doing the right thing, and helping those less fortunate than you. And practicing compassion.

Did I just hear you say “follow Christ’s message”?

I’ve been studying the Christ myth and it’s the best. Of course, it’s misguided and has been

misused and abused. But he’s like the Yoda of Christianity! That guy is, like, good, but of course you can’t use that word in our culture industry. That word is like a dirty word because those values have been so distorted and perverted through the corruption of the church. But in essence, it’s good stuff.

What role does art serve in your life?

Art is everything. It’s the most important thing. It’s what saved me and it’s what I’m most dedicated to.

“I found my own internal standards of excellence rather than that of those around me. I think that’s what all successful artists do. They find their own standards. They make up their own rules that work for them.”

How did it save you?

I had a very unsuccessful childhood as a C-minus student. I was bad at sports, I was unpopular, I was generally unhappy. When I first started to make art, I stopped biting my nails, stood up straight, gained some weight –

And started coming to Tokyo.

I started meeting people that were aligned with my thinking, so I didn’t feel so alone anymore. I grew up in a place where it was only about athletic performance, about getting picked first in baseball and not picked last. Bottom line: I found my own internal standards of excellence rather than that of those around me. I think that’s what all successful artists do. They find their own standards. They make up their own rules that work for them.

Which is, in essence, authenticity.

Yeah, and making it up is fine. It’s not the only way. People find authenticity in systems and cults and tribes, while other people have to make it up for themselves. They are all different kinds of success.

How do critics affect your practice?

When I went to college, I was very successful academically because I finally had something to care about. Whether it was philosophy or physics or critical theory, I found a way to al ways make it about my art, or to make those subjects interesting, because I found a way of applying them and of finally applying myself to things that were outside of my immediate area of focus – in order to see how everything was interconnected. I spent a bunch of time reading theory and even writing some of it, and there’s been different degrees of acceptance and rejection of what I do. Of course, we all want to be liked, but sometimes people don’t like what you do. It doesn’t really feel good, but it also doesn’t really matter, because I spent a bunch of decades – really, like, two and a half, almost three decades – being unsuccessful and having to find my own standards of excellence. If someone doesn’t like me, I’ve learned to develop a thicker skin to deal with it. One of the reasons you make stuff – art, whatever – is because no one has done it before. If someone’s done it before, there’s no reason to do it. But that also means that you don’t have a lot of support, since people don’t understand it, because it hasn’t been done before. It’s one of the great paradoxes of making sculpture. Why would you make a 12-foot diameter NASA meatball logo and make it all in white? Why would you make the world’s largest representation of the World Trade Center? Why would you make a Japanese tea garden? You are not Japanese. For all these questions, there isn’t a good logical reason, but my job as an artist is to educate and entertain myself, to understand myself and trust myself enough so I can go out there and make that wrong decision, that “right wrong decision.”

It’s more than simply, “No one has done it before.”

Yeah, that’s not really a reason. This is always an issue I have with my friends at Nike – there’s a culture of innovation that we all have, not just Nike. It’s also in the studio. We always want to do something new, but nothing is new under the sun. We have to innovate only when absolutely necessary. I always try and do as little as possible, and within that, as you can see, there’s a tremendous amount of work that gets done. But the philosophy is to do as little as possible, to use as few words as necessary, and to make the movies as short as we possibly can. I don’t think it’s important to make a movie 70 minutes long, which is the absolute minimum for festival submission on a feature. We tried it and the movie really should have been 65 minutes long. I think it’s important to make the thing what it wants to be and let the world catch up.

Recently you said, “John, do you think my films and videos should continue? Are they important?” And I said, “They’re an integral part of your practice– that’s how I feel.” What is your practice?

Sculpture first. We make sculpture here. The movies are there to represent the aspects of the sculpture that exist in time. If an object has some utilitarian function but it’s on a pedestal because it’s in a museum, and you can’t use it because it might break or get fucked up – that’s one purpose of the movie. The other purpose is to show the ethics and values of the studio, because art is a verb and an action, so sometimes you don’t really see all that went into it. The stuff that went into it is people’s time. The values of the studio, how we do things, we transparently show through the movies. I always admire those artists who speak cryptically or not at all about their art. Some of my favorite artists – like Joseph Beuys – talked a lot about their art, but no one knows what the fuck’s going on. Love that guy! I could never be that. I think you assign all kinds of intelligence to someone like that, and it may or may not be there. You assume it’s there, but, in the end, no one knows, because no one can explain it to you. I went to college. But the people that write about Beuys went to way more college than me, and some of those people are really smart and still can’t explain him. But I’m not one of those artists. I want to lay it all out.

This is actually a major topic between my two sons.

Yeah?

I like things that are really clear. If I’m going to communicate something, I want them to understand what I’m trying to convey. But there’s a whole art form of avoidance of clarity, avoidance of making it clear, so that there’s this magical, mystical –

It’s bullshit! It’s a lie, it’s a scam, and it’s dishonest. People hide behind overly complex words to cloak their own stupidity. This is the problem when you read Artforum!

And architects speak the same way?

Yeah – fuck those guys! But the really good ones don’t need to. The really good ones are straight shooters. You hear Frank Gehry. He doesn’t use complicated words. He lets the works speak for themselves. He’s happy to explain them, and if you ask him about the crazy curves, he has a reason.

Academia is part of the critical crowd that forms this wall between art and commerce.

But we are taking that down – our generation. I think that’s what we are doing with Nike. We are reaching all kinds of people who would not be into art, but they come in through the sneakers. Sneakers are art, fashion is art – it’s all different forms of art. Cooking is art. Music is absolutely art. The only collection that I truly have is my music collection – that’s why I’m so pissed off at Apple right now. iTunes is a mess – it’s all scrambled. But I guess my point is: we are melding, and also, we did not invent this. I think the artist that I most look up to is Isamu Noguchi, who is the ultimate hybrid artist of the 20th century. Not American, not Japanese, and didn’t feel at home in either. Arne Glimcher of Pace Gallery said his job was keeping Noguchi away from Knoll and Herman Miller, but Noguchi is most famous for his lamps and chairs and stuff. His best works are his late basalt sculptures from the 1980s. Those were the best things that he made. He had an incredibly diverse career and didn’t give a shit what people thought. This is a guy who made $100 lamps and $1 million stone sculptures, and did it all. Another great artist to talk about is Joseph Beuys, who made multiples in editions of 5,000 so everyone could have them. He was also a political artist and was interested in restructuring economics and power systems. Beuys and Noguchi were interested in ideas first, and understood commerce as an illusion by which we all live and die. They had to make ends meet, but they made things that were cheap and things that were expensive. I’m interested in making things that support the rituals of my community.

When we do a pair of sneakers, it’s sneakers for our team, which includes the dozen people that work here, you guys sitting around this table, and our friends at NASA who worked to put a rover on Mars. We work together, so this is for us. When you, John Doe on the street, see that shoe, you become a part of us. It’s sort of like when you wear a Yankees hat, you are a Yankees fan, but you are also a part of the larger team. When you wear our sneakers, you are a part of our larger team. When you go to one of our exhibitions and you see a sculpture, you are participating by viewing the things. Andy Warhol said something like, “The Coke that you drink is the same Coke that I drink, that the Queen of England drinks.” The Coke is a Coke is a Coke is a Coke. There’s a great democratization of experience because the most valuable things in life are free. The expensive things in life are not that important. There’s a slope, or degradation, of importance as you spend more money, right? You can have a million-dollar supercar, and you can have a Subaru. And the Subaru is actually going to get you to Patagonia first if you have to race.

When I think of some of these other artists and if I buy their whatever, I’m not so sure I’m part of their team. I bought something, I like it, it’s cool, it’s interesting, but I don’t feel I’m part of their team, their studio, their practice.

Well, I don’t know if I’m successful with this claim, but I’m going for it. I’m aiming for that because I think that we can make the world better through art. Or, I should say, things are very fucked up. It’s really hard to find a cause. Orcas are dying because the salmon can’t swim upstream to spawn because of the dams, so we’ve got to take down the dams that we don’t really need, but they are creating electricity. There are some big problems, and we need to get off of the petroleum cycle. What’s going to happen with all this lithium battery waste? I haven’t heard a great explanation yet. Does that make it worse, or better? I guess all we can do is be responsible for our surroundings. We aim to make heirloom products be cause, before you recycle, you want to reuse, and, before you reuse something, you want to make sure that it’s durable and will last. That’s always the goal: to make things last longer. People exercise to make their bodies last longer and to make the quality of their lives better. That’s one of the reasons we use non-exotic materials whenever we can, and use materials that had a previous life. When we have to fake it to tell the story, we do so sparingly. It’s not just about being economical – it’s also that those materials have had a prior life, so the story’s richer and there’s more authenticity.

You mentioned you struggled as an artist for a while. Is there a particular moment where a bridge appeared and you crossed over?

Yes, it’s a very precise moment. I was working for Frank Gehry in Santa Monica. We needed screws, so I went to Busy Bee Hardware. There was this dirty old hippie behind the counter. He said, “May I help you?” And I said, “Yes, I need some screws.” He’s like, “What kind of screws?” And I said, “Any old fucking screws! I don’t care. It’s not for me, it’s for my job.” And he said, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, kid! Once you realize that your job isn’t for your employers but that it’s for you, you will be free. And the world will shower you with opportunities.” And I was like, “Yeah, yeah, yeah – give me the screws.”

A couple weeks later, I quit-slash-got-fired and moved to New York. I got a job where I was getting paid even less. I was a janitor. I had a degree, I had done my apprenticeship, I was a very high-level woodworker. But I was a janitor. I was cleaning at Barneys New York, doing the windows, cleaning and painting and making it nice for everybody else. But I was really the lowest person. I remember there were other people I was working with, and I was really like, “This job sucks, but I’m going to make the most of it because this is what I’m doing right now.” I remember the other guys got really mad at me. They said, “Tom, you are making us all look bad because you are working so fast and you are doing such a good job.” And I remember – I was such an asshole – I was like, “Damn right! Yeah! I’m going to do a better job! Watch!” They hated me. But three weeks later, I was their boss. Three weeks after that, I had my own team, and I was driving around to different stores and leading the window displays. I was designing stuff, I was building stuff, I was making furniture for them. I had money to build up my team, and I was using that extra money and time and crew to build my sculptures at the same time. The money, to quote Phil Knight, is automatic when you do a good job. I took that philosophy and I teach that to everyone here on my studio team. No one is here for the money. We are all here for the doing of it. People that are here for the money don’t last long. They may automatically leave. They get fired, they quit, whatever. They are just stuck. They don’t belong. Everyone here is here because they believe in these ideas.

How have you evolved as an artist?

I’m fatter.

Aren’t we all? Is the question presumptuous?

It’s just not really the answer that I want to give. I mean, it’s a process, right?

“Everything that we make is unmistakably Sachs. You can see there is a very fine line of shitty and perfect in everything we do. You can always see the screws, the pencil marks, the glue drips, and the cum stains. It’s all over it, and that’s what makes us special.”

I still have a video of you walking me through the show “Sony Outsider.” I believe there were some good critiques after that show, asking, “But where’s the Tom Sachs hand?” It didn’t come from a small critic either.

That was a big transition, so I loved that. I really don’t pay attention to critics, because they don’t usually have great ideas, but that one was. I don’t know if I would have gotten there on my own. But I noticed it when I made this sculpture as a model of the atomic bomb. I went to the shop where they were doing all the fiberglass and paint work, and I walked in as they were spray painting it over in white. They were erasing all the hand sanding! I was like, “wait,” but I hesitated, and they painted the whole thing – once you start, it happens in just a few minutes. The critic wrote that there are many artists that could have made this type of work. I don’t want to make something that’s so perfect that someone else could have made it. So since that moment, I have really made an effort to do it the way that makes it look like me. Everything that we make is unmistakably Sachs. You can see there is a very fine line of shitty and perfect in everything we do. You can always see the screws, the pencil marks, the glue drips, and the cum stains. It’s all over it, and that’s what makes us special. I did a talk at the show in Germany and there was a question from the audience: “Why do you use these Phillips head screws and not the square drive screws or the star screws? They’re so much better and don’t slip out.” I said, “Yeah, but those are exotic, specialty professional things. I want to use things that show that this is made by human beings in a shop.”

Apple makes the best-made thing ever. No one’s ever going to make something as good as an iPhone. It’s a perfect thing, but there’s no evidence that a human being was involved, even with the software, by the way. But I would argue that the work we are doing here in the studio is much more mature and evolved.

Last question for you. There’s a lot of people coming out of art school, a lot of people who have dreams of being an artist, and they look to you. What’s the lesson for them?

NUMBER ONE: Keep yourself alive. Really easy. Get a Zojirushi rice cooker so you don’t need to worry about food and because it’s the best deal. Yes, it’s $300, but it really eliminates guesswork and you can focus on other stuff.

NUMBER TWO: You are an artist right now. You will not become an artist. Day one is a point of no return. You start now. That’s the only way you’ll ever make it – just deciding that you are there already. I remember that moment. I went to a pretty progressive school that was very supportive of this kind of thinking. I was treated as if I was a professional artist even though I had never had an exhibition or anything. There was a very supportive community of people who took each other really seriously. Making it as an artist is really hard and rare – you have to believe. If you don’t believe, it won’t work. But if you do, you can absolutely make your own set of rules that works for you. Anyone can do it, but not everyone necessarily wants or is willing to. It’s up to you. It’s not like you are not going to get a “break,” like you are waiting for the opportunity or money. You create the break. You have to be willing to and to want to do it. There are no exceptions to that. There are a lot of different ways of becoming an artist, but that aspect is 100 percent universal and true of every artist, every professional basketball player, every successful businessman, every great lawyer. They all have that same attitude.

Credits

- Interview: John C Jay

- Photography: Jason Schmidt