DEAR LUCAS SAMARAS (1936-2024)

On the occasion of the passing of Lucas Samaras (1936-2024), the American artist “who was his own canvas,” we’re republishing a 2009 interview with Samaras.

“It means I’m connecting to something real, something that happened, something that has automatic substance.”

It was five decades ago to the year when Greek-born LUCAS SAMARAS had his first solo exhibition, which took place at the Reuben Gallery in New York. It was also in the NYC of the late 1950s where Samaras began to participate in happenings, and work alongside Allan Kaprow, Robert Whitman, and Claes Oldenburg, to name a few. This year, half a century later, Samaras represented Greece at the 53rd Venice Biennale; his multi-installation work, “Paraxena,” included a five-and-a-half-minute iMovie centered around the artist undressing in his 56th Street studio – atypical in both activity and medium, perhaps, for an artist whose year of birth predates WWII. Samaras’s practice has never been typical of its time, though, but forever a move ahead. “Paraxena” was the discreet gem of Venezia, its video pieces attracting the participation of a multi-generational selection of luminaries, Chuck Close, Ingrid Sischy, and Jasper Johns among them. Behold the artist’s influence and influences, and a body of work as broad as it is dynamic, investigative, insatiably thirsty, and perpetually regenerating. Meet Lucas Samaras.

At some calculated moment, I imagine, in the privacy of his study, Jacques Lacan would set his thick but active hand on a panel in a frame on the wall, and, under the great psychoanalyst’s guidance, the perfunctory drawing of hillocks and trees would slide away to reveal one of art history’s most notorious treasures – “The Origin of the World” (1866). This is Courbet’s cunt rising from behind a veil, a work that brushes cliché, but remains an indefatigable icon and a relentless engine for fantasy. In the hands of Lacan, it was also art in the service of psychoanalysis. Why then would the psychoanalyst suppress such a dynamo image behind a panel, even if it offered an ironic hint of what lay beneath?

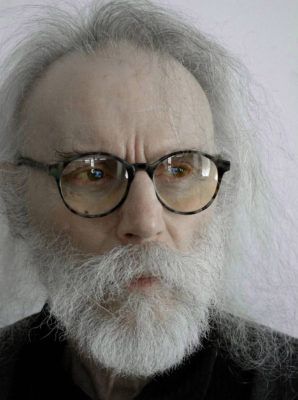

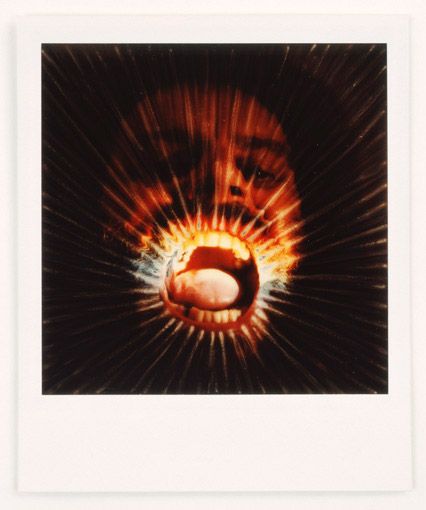

On July 23, 1982 the prolific American artist known as Lucas Samaras completed an untitled pastel, which, I’ve come to discover, is the perfect answer to Lacan’s perverse little paradox. A symbolist image of sorts, it might have been a quiet vision of the sun on the sea were it not for a monumental penis erupting from a cobalt sky, pointing a middle finger at the slender meniscus of the sun perched on the water’s edge. It is impossible to lose the priapic monster in its landscape, or ignore it behind a polite façade. It is the most dominant element, glowing with a subtle light from a second sun hidden somewhere outside the frame. Samaras’s pastel could easily be titled “The Origin”, the penis having just discharged the world, or, on the contrary, aimed for its destruction.

Lucas Samaras, who once flirted with a career in psychoanalysis, is also a science fiction movie buff, I learned. He recommends almost any B movie from his teenage years, like “War of the Worlds” (1953) or “The Day the Earth Stood Still” (1951). He loves the solitude of empty landscapes, which, in movies like these, result from alien attack or historical cataclysm. These movies also challenge, albeit in melodramatic ways, the comfortable, narrowly defined, middle class lifestyle that Samaras never wanted to be a part of, especially in postwar, McCarthy-era America. If there were a B movie of his life, his pastel “Origin of the World” would surely supply the poster: it is the older Origin’s mirror image thrust into the middle class eye. Earnestly defiant art works like this, lovingly crafted and radically considered, have been Samaras’s central occupation for the last half century.

Playing the role of a modern day Diogenes – a “fithy artist and not a prince,” as he has said – Greek-born Samaras has made an example of his solitary, humble existence, carrying a brazen light to the zenith of the art world all the way from public school in West New York, New Jersey. With a multifaceted body of work, which can be hard to grasp, Samaras came up among a generation of art gods whose names conjure ready images. The unacquainted might first see his work on their terms: Samaras is precise like Chuck Close, syncopated like Frank Stella, succinct like Jasper Johns, acrobatic like Mark di Suvero, abrasive like Hans Haacke, and resourceful like Robert Rauschenberg. Yet, “Lucas’s work is unique,” says Arne Glimcher, who signed Samaras on to Pace Gallery in 1965, shortly after opening in New York. “He creates intimate little theaters,” Glimcher explains, and “unfortunately, the art world has been built on scale since abstract expressionism.” In a sense, Samaras is the touchstone by which his out-sized generation can be reevaluated, a mirror image to reconsider the pantheon of art both past and present.

In his 2006 piece “Ecdysiast and Viewers”, 24 videos document the facial reactions of 24 individuals to a digitally distorted movie of 69-year-old Samaras posturing in the nude.

The audience on which he trained his camera included, among others, stewards of his career like Glimcher, editor Ingrid Sischy, and curators Marla Prather and Bernice Rose, as well as fellow artists Close, Oldenburg, and Johns. Ecdysiast illustrates a basic equation of Samaras’s work – you and him, him and you. By hooks of curiosity, voyeurism, distraction, disgust, or lust Samaras snares his audience, whether it is a self-portrait where he writhes naked in a jungle of pattern, an erect rose over his cock, or an intricate box construction begging to be manipulated. In a 1979 interview with art journalist Barbaralee Diamonstein, Samaras’s voice rises to a high pitch for a single resonating moment, exclaiming, “I want to use people and then they can use me!”

Samaras placed me in front of his camera at one point during our conversation, while Tchaikovsky’s pageant to metamorphosis, Swan Lake, played in the background. He mentioned in passing that he often finds a way to “restructure” his interlocutor. I had come to him with a blank slate ready to record his every word, but brieß y the tables had turned. Thinking back on my conversation with Samaras, I must have been experiencing that old surrealist technique called “frottage,” a rubbing that is sexual in connotation and psychologically liberating. By 1979, having achieved the bulk of his famous work with Polaroids, Samaras was able to claim that he had liberated narcissism. This, however, was not granting the same indulgence offered by pop art. For one, Samaras draws from the complex dust-covered tangle of history. In his treatise on painting, Leon Battista Alberti jauntily placed the origin of art in Narcissus’s classical trauma, at the very moment of embracing beauty, so enticing and so elusive. With some help from Samaras, that very license was now mine for the taking.

PIERRE ALEXANDRE DE LOOZ: Can we do this naked?

LUCAS SAMARAS: Aha! Well, you have the advantage over me because you are younger!

There is beauty in every age.

Not really.

The image that keeps coming to mind when I think about your work is the Shroud of Turin.

How does it connect with me?

First of all, it’s a portrait.

But it’s also a fake.

And you’ve been accused of theatricality.

How can anyone accuse anyone else of theatricality? That’s ridiculous. You are taught theatricality from the age of two or three.

Perhaps the moment you start language.

Perhaps even earlier because others smile at you. They draw a smile out of a baby. They squeeze it out of you and then you are sunk. You have to perform otherwise you don’t get your milk.

So, theatricality is a basic condition of living in society.

But not many people study it professionally like actors. Some do it automatically and are very good at lying, whereas others have to work at it. There’s both a connection and a difference between theatricality as a manipulation of people and pure living. In life you automatically express desire. For example, when you want to get something from somebody, you might have an expression like, “Give it to me or I am going to kill you.” On the other hand there’s the mirror. Without the mirror all you have are other people’s reactions to the way your face moves; you don’t know how you look when you threaten people, or you say sweet things otherwise. You learn to respond to this like a monkey. You learn “that’s you there” and, “this is the expression you are making.”

You remind me of Lacan’s writings on the role of the mirror in developing the self.

People living in the jungle have no mirrors, and yet they function pretty well. So how does it refer to our conversation?

Many read your work as if it is autobiographical. It’s about you. On the contrary, I would say you are being the mother, and we are your children.

There are obvious referrals to biographical changes, but as to whether it tells you much about my life is questionable. If you are looking at a picture of serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, who killed 20 kids, chopped and ate them, can you read any biography in his face? Impossible! Seeing Hitler in Berchtesgaden playing with his dog, you could think, “What a wonderful uncle!” He’s dressed nicely, he’s not a bum. You know nothing about his biography. Moreover, when American female photographer Lee Miller posed for a picture in Hitler’s villa, taking a bath in his tub, it’s questionable whether it tells you something, whether bathrooms and beds tell you something. So in my case, it might be a partial biography.

Did you ever want your audience to know who you are?

Those of us not born aristocrats realized at a certain point that there were people living in more spectacular residences than ours, and we become extremely annoyed. You then either work hard to get there, or you say, “Fuck you, this is where I grew up, take it and shove it up your face!” I think my work had that kind of aggression behind it. Anybody who is worth anything has some kind of aggression, and then if they are lucky they change it into professional energy. If you were a minimalist, you just painted something grey and then you said, “That’s all you are going to see,” which is a Germanic kind of aggression. For me it was simple: I made something with pins. For many years I had to sew in a fur shop, and I detested every minute of it. In my mind, a leap was taken to change fur into pins. They look like hair, but they are dangerous; so it was that kind of thing, where you don’t consciously try to make something aggressive, it just happens.

As the viewer, am I supposed to feel these pins coming for me?

No. You are supposed to feel a dazzle. And then you say, “Ooh, I can’t touch it.”

So you can’t touch art?

No.

In 1998 you had a show constituted exclusively of solid gold jewelry, all wearable pieces that you designed using chicken wire as a template. Is art really the luxury item it pretends to be?

Yes. Art is classified as a museum piece, just as ornament in architecture, which was banished for 50 years, can be found in museums today.

Don’t you think recent hyper-evaluation of the art market merits commentary? Take, for example, a certain skull covered in diamonds, not unlike a head you did yourself in 1965.

Yes, these prices are a monstrosity, especially for junk. But nothing prevents you from working with any substance. I was working with glass stones and tinfoil. I remember in the 1960s when Mark di Suvero had seen one of my boxes, he asked if I would like to use real diamonds and rubies. But that wouldn’t be a challenge for me. A jewel already has a value. Although, when you see a box holding a saint’s bones, or a Bible covered in jewels, it can be spectacular.

Perhaps your generation’s aggression or source of shock was that of the anti-value. Do you still believe in this kind of art terrorism?

I don’t want anyone to be a real terrorist.

I mean smearing shit on an image of the Virgin Mary.

Privately, those kinds of things can be done as a joke – why not? However, I don’t think you have to rub it into the culture’s face. Within a small group you have permission to make fun of anything; but if you include outsiders, it’s another question. I guess I am from the old tradition: you can do negative stuff as long as you equip it with craft. I like controlling the demons. They should not control you.

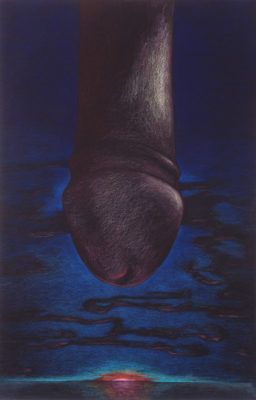

Lucas Samaras lives in a meticulously ordered apartment, the product of daily discipline. His routine starts at 5 a.m. and ends at 11 p.m., after five hours of prime-time television and twelve hours of work, which now often occurs on a computer with wide-screen displays continuously streaming video. It is a far cry from some fabled SoHo loft, and even farther from the cramped, dark West Side apartment where Samaras used to live and staged many of his photos. To reach him I rode a high-speed elevator to the 62nd floor of a post modernist complex in Manhattan’s Midtown. Samaras opened the door without a word, and gestured that I enter, landing me in a scene from J.G. Ballard’s “High Rise”. Thin, long, and silvery at 72, Samaras moved with the grace of a greyhound through the apartment of his own design, the center of which seems to be a cross shaped gallery of his work. The space is lined with shiny vitrines, silvered curtains, and drips with many of his token knickknacks, a densely packed miniature museum. The shades were down and French symphonic music, what Lucas calls “heavy seduction,” massaged the air as we spoke.

To sketch out two general display techniques, there’s the minimalist grid on the one hand, and the wunderkammer on the other. Is there a right way for you?

I’ve never been strict about keeping to a system, like a salute every time you come through the door. I started with the Green Gallery, where it went over the top when I presented my bedroom. I transposed whatever space I was living in at my parents’ New Jersey apartment to the Green Gallery in New York. Same bed, everything. It was scary for all of us, me and Dick Bellamy. Dick didn’t have any money. He had to scrounge for all $700, which, in 1964, was a lot. And who knew what would happen? Would it be built right? Would it look right?

Was it a show to sell, or was it a show to publicize your name?

Well, there was a picture in The New York Times after the show opened that said, “Samaras offers his bedroom for $17,000!”.

Whoever bought your bedroom must have paid more per square foot than you did for this apartment!

My bedroom was bought by the Salvation Army. They took some of the furniture. It was ridiculous. As for the art, who cared about art that much anyway? I took it with me.

The bedroom was a kind of display case?

Yes. It was a room that was built into the gallery. You could call it an environment, but for me the idea was that it was a closed thing. You open the door and you are totally enveloped. It was as close to a biographical presentation of a bedroom studio as anybody could give you. I took the direction from van Gogh, but there are other historical examples, like Mondrian’s studio and Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau. Plus, there are the fantastic period rooms at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; or, on a lower scale, the furniture showrooms at Bloomingdale’s.

It’s interesting that you group these references together. The period rooms at the Met are often constituted from private collections. They tell a story about how material culture was digested, from the origin to the collector to the museum. Were you implying the consumer system in your piece?

No, not at all. We had a slightly different view of the collector. The 1990s killed the whole idea of collecting as a distinguished process. When people went from having a million to having a billion, connoisseurship, which is kind of snooty, but an extremely essential ingredient for art history and the continuation of historical perception of art, was watered down.

So is art in a vulnerable place now?

Totally. Art is endangered from everywhere now, and a virus is also afflicting artists. They are doing anything other than making art themselves, and they create defenses for it. They are intellectuals more than craftsmen, and they have taken over the media. Oscar Wilde or Diogenes, and I’m sure there are others, had a way around this. Surrealism is one approach that works. It has some negative aspects, but instead of just taking Raphael and making Pre-Raphaelite work, it changes how to look at something. Then you have somebody who throws acid at the Mona Lisa, which looks like a Raphael anyway, and that person could be an artist.

Are you suggesting it’s a problem? Isn’t this how art moves forward?

Not if you destroy the past. You can destroy it verbally, but if you destroy it physically then you are a fool! We had an example before the Twin Towers fell. Those stupid people in Afghanistan blew down the two statues of Buddha in Bamiyan. To me, that was the most tragic event in years concerning art.

It was ominous. Perhaps out of your deep respect for the past many references are thrown up about your work, so much so that you highlight a problem faced by the history of art: coining movements doesn’t always make sense. How do you feel about that?

There was a time when I was able to go to the MoMA and see Cézanne, Rousseau, and van Gogh, from one room to the next, like following the history of art, and it was wonderful! Then we created a jungle of how museums should present collections – I hate it. I think I am above it in my work. I like the movements that occurred before me, and I like to be able to add something to each one if I am able to. Obviously my hands can’t do Renaissance stuff, but even in photography you find that you do something that could be a little snippet of a historical painting. I obviously couldn’t reproduce the whole thing and wouldn’t want to.

Do you have some favorites?

My education comes in part from the French school, impressionism and post-impressionism. I like that stuff, and Byzantine art. Vuillard, for example, was able to make art that always looked like it was appearing and disappearing. His work also involves fabrics, design, and ornament. It has intimacy and none of that stupid bravado, or someone flexing their muscles. I grew up with women. I was stifled with women for the first part of my life. I knew everything there was to know about femaleness. Vuillard’s painting at the MoMA of two women, one shrouded in a black dress and the other disappearing into the wall, resonates. It automatically gives you a drama, but it has a spectral quality that is beyond reality. To me, it is one of the great paintings. I’ve seen others where there are wonderful colors, and color to me is king.

In many of your photos, and almost always in the “Photo-Transformations,” you have two major poles, green and red. They are polar opposites, and the most high-contrast colors for our eyes. Why did you use these?

Well, for me, colors have an intensity that should be embraced– you know, when you are a child and somebody squeezes you. You have to have that squeezing … “I can’t breathe!”

Is that why you’ve often used the rainbow?

The town I grew up in had no art per se. There were churches with old fading frescoes of saints. But there was none of that flowery, brilliant kind of painting that existed in museums. So obviously a rainbow would take care of that – all of a sudden, some trees, some sky, and then boom, a magical event! In the late 1950s, when I started using this rainbow sort of effect, it was like heaven. It wasn’t something that the artists in New York were using. They were using earth tones and black. I have a drawing from high school that has the rainbow colors.

Much like your contrasts of green and red light, you’ve collided hard and soft in your work, which you share with Claes Oldenburg. What’s the connection?

Unfortunately, critics zeroed in on Oldenburg’s soft sculpture. They said he was the soft man. They neglected to really look at my work using pins and wool. I guess they were frightened by the pins, and could not see there was softness underneath it. Why did you bring up that subject? Did you know it would upset me? I do it for the same reason that some people work very hard to develop a style and then stick to it. For me, it became an adventure or a challenge to be able to go for one thing that had some qualities, and then something else with totally different qualities. Hard and soft have that. It is basic to my nature.

Early on you studied with a radical innovator, Allan Kaprow. What was your relationship with him like?

He was my teacher and gave me the scholarship to Rutgers. He had access to the New York avant-garde, and that’s what I got from him. He knew everything about the art world, and I knew nothing.

Did you learn anything from him conceptually, or in terms of craft?

You learned from everybody. You picked up hints here and there. Then you decided to go one better than them if you could, or as good. My group had certain gods like de Kooning, whereas the other group had Picasso.

Tell me about the early happenings. What were they like?

People denigrate the happenings, which is very frustrating. The happenings were created by young working artists who were showing in galleries. These weren’t people still in school or doing carpentry for a living. Secondly, they created environments, and they were organic. They were organic in the sense that an artist living in the 1960s, not having much money, lived in a dirty old loft, and you had happenings in a dirty old loft, with the dust and derelict furniture, with the smell of old and maybe a little piss. Entering the loft, automatically you were placed in this dump. The artists were part of the dump, or emerging from it. There would be some painting activity taking place, or other simple gestures, but the whole thing was enveloping. It was based on reality, but it was a little unreal. The audience sat only a foot away. Dancing was a big deal in those days. You had an invasion with Yvonne Rainer, Simone Forti, and the Cunningham group. Although, with happenings there was movement; it was based on real specific gestures. With Allan Kaprow, squeezing a lemon was presented as such in a gallery. With Claes, the lemon and the gesture were transposed. It had nothing to do with Warhol’s Velvet Underground and all that stuff. That was, from our point of view, clean, cutesy, stupid junk. What we were doing was real, serious, and totally interesting.

What do you think the audience got out of these happenings?

I think they got something poetic, and something that hit them in the gut. It wasn’t like going to a party. It had a scary component. It was like going into an old dark cellar. It wasn’t like giving a lecture to a dead hare either – I am referring to the Joseph Beuys performance (1965).

What were your connections with Andy Warhol’s tribe?

I was part of the group, but at a distance. Andy was somebody you saw when you went to an opening, or if you had a party. I consider him one of the people who created my atmosphere. We talked briefly about making a film, but I wasn’t quite settled as to what kind of film I wanted to make. And on the other hand, I didn’t want to be devoured by his machinery.

What did you think of a movie like Sleep (1963), which really resonates with some of your later “AutoPolaroids” (1969–1971)?

In those days, Andy’s group would go to somebody’s loft and show movies at night. I remember going to one of these evenings and seeing Sleep. After two or three minutes, I remember jokes; conversation had to take the place of nothing happening. They were interesting philosophically, but I hated the films. They were junk. The film was bad stock. It was not like seeing Ansel Adams on Mount Rushmore.

Tell me about the first movie you appeared in.

It was Raymond Saroff’s movie The Real Thing in 1964. Saroff came from the fashion business. He also filmed some of Oldenburg’s happenings, so he was around. His idea was to compare commercials from TV to actual sex acts from a dirty movie. He kind of liked my work, and he thought he could use me as a kind of underground element. I had a headshot from when I was trying to be an actor. I am not sure it’s in the film anymore, but I taped Xeroxes of my headshot on commercial posters, over people’s faces. Afterwards I removed them.

Was it vandalism or self-promotion?

In the early 1960s, before graffiti artists came into the picture, graffiti was infantile, dirty, crude; writing “Fuck you” or “Fuck your cunt.” Or, it was simply chewing gum on posters. So putting my head up as I did was introducing a high gloss art world thing into an everyday space. And it has had a strange resonance in my work now.

Why did you train to be an actor? To be famous?

Fame is part of it. But the other part is getting satisfaction, and proving yourself as might a lawyer or a doctor. It is making society accept you in a profound way. It’s like becoming a god and entering into society’s dreams. It’s a good thing I finally rejected being a movie person, because I was able to do it all as an artist.

What did you learn from acting?

In acting school, they teach you to look at yourself, similar to a movement or gym class. You are seeing your body, really, for the first time. After all these years you know how to comb your hair in one way, and speak a certain way. You grow up with your body, and then all of a sudden you see yourself the way others see you and criticize you. It’s an education of how you and your body react to the world, in real space. It’s absolutely major. You learn how to manipulate your body in a more complete way than you had been doing before.

Is Lucas Samaras a role?

Yes, absolutely! For example, at a Guggenheim opening in 1961, which everybody attended – the art world was smaller then – I didn’t know most of the people. I finally went to the top of the ramp and stayed there all evening. Then, at a certain point, Alfred Barr from the MoMA came up the ramp to me and said, “Boy you stayed here all night!” It was a nothing thing, but it was totally meaningful to me. That was an acting thing.

Susan Sontag, for whom you may have mixed feelings, felt that the original purpose of art might have been to be an instrument of ritual.

My bête noire! She had a blind eye when she saw me! And you know the reason? It was very personal and private. That is, she was emotionally involved with a friend of mine. I am not saying it was erotic, but it was an emotional attachment. And she came to visit her one day in her studio and saw me there, sitting on the floor. It was obvious that something in her said, “Who is this guy?”

What do you think of her calling for an “erotics of art”?

She was an idiot! What was I doing all this time if not erotics?! She wrote all about photography, and she saw nothing in me. All she saw was the stupid advertisement using my work, which the Polaroid Company had used in Time magazine (1972). That’s the reference she put in her photography book, next to a quote about Ansel Adams. She was absolutely blind.

Because you were too real? I was amused to find out that you’re inspired by pornography.

Pornography is part of your education. If you haven’t seen any you must be a moron, or just dead. It shows you things you hadn’t thought of, like nudity. I grew up hardly seeing nudity, not to mention close contact. When I would take a bus from New Jersey, where I lived, into New York, at the 42nd Street Terminal I would pass by bookstores with nude pictures. Having experienced years of that, I said to myself, “What the hell, that was part of my education. Why can’t I take my clothes off?!”

It reminds me of your statement about the child learning to smile by looking at the mother. You are describing a duplication of a gesture in your appreciation of pornography. It’s the same theatrical mimicry.

Though sexuality does begin with the mother, as you get older you stop looking for the mouth and tits, and you look for something else. Pornography also provides you with schema, how to present the human body. And many times it’s very close to Renaissance religious paintings. Artists used to go to life drawing classes in the old days, and that was also an entrance into dealing with your own body. Just as the so-called primitive man might have drawn the shape of an animal about which there was something religious, similarly with us as with children, to draw a naked person is exciting, a mysterious sort of excitement. I can do totally erotic, shocking stuff for only a short period of time, and then I stop, put it in a nice format, and go on to the next chapter. After 40 years, when you do it again, you have to treat it differently. Obviously I am not what I was, which is why it probably took me so long before I could find a way of presenting my body again.

Is it true that when you showed the “Photo-Transformations” for the first time in 1969 – the same year as Woodstock –your friends and curators thought the images were excessive?

I had a psychiatrist friend, a brilliant guy, who thought they were terrific, but was embarrassed. His wife liked everything I did, so she automatically liked these. I showed them to Ivan Karp, who had a major position in the art world at the time, and he was horrified. His wife may have been slightly interested. I even took them to the MoMA, but there was some kind of hesitation. However, I got the strength to show them to Jean Lipman, who was editor of Art in America. I brought one of the albums with me to dinner, and her reaction was just heavenly.

If you didn’t win over Sontag, you managed to convince quite a few other females. Is there a difference between erotica and pornography?

I wonder if I am telling you something about myself … Concerning eroticism, the pornography that was available before the 1960s was more erotic than the pornography that came afterwards. Beautiful bodies do not produce erotic situations for me, you understand? I am not talking about real life. I am talking about looking at pictures. The dirty pictures, things happening in dinky rooms, ordinary people – there was this unbelievable drama!

Then pornography became overly art-directed and super banal?

It’s like Penthouse. To me, it’s the most banal junk that exists. I can’t stand the women who pump up their breasts like balloons. Once you’ve seen it, and you know that culture exists, you don’t want to see it again. There are a lot of things like that in life. Then eroticism is sublimated, which is what artists like to do.

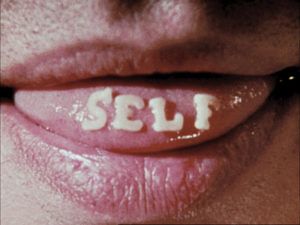

What’s your favorite body part?

When I talk to people I look at the mouth. That tells me more about a person than any other part.

Of all the body’s orifices, Samaras privileges the mouth as a point of entry. In his “Auto-Polaroids,” it appears contorted and compressed just above his crotch, or made up in drag or biting a cigar. It is one of the fiercest characters in his later “Photo-Transformations,” and it is arguably the alter ego for all of his boxes, which swing ajar to reveal their guts. It is also one of his earliest motifs. As early as 1961, Samaras made an untitled object from a cracked plate, held together with a thick amorphous material resembling coagulated porridge into which he stuck two glass eyes salvaged from his sister’s doll, and a spoon. This thrifty surrealist object seemed to say, “Eat me,” implying the viewer’s mouth as the unspoken participant – and it worked.

Starting with the MoMA in 1961, Samaras has been consistently and widely consumed. Institutions and patrons alike, from Fort Wayne, Indiana, to Canberra, Australia own his work. The Tate in London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York are no exception. But, the most compelling indication of his sustained performance over a half-century is perhaps that fellow artists count his creations among their prized possessions. Donald Judd placed one of Samaras’s boxes by his bedside at 101 Spring Street, but Samaras complained to me that it had not been properly mounted in a vitrine. The box was not a gift. Judd purchased the piece, as other artists like Cindy Sherman and Bruce Nauman have done to obtain a Samaras.

Though the case of Cindy Sherman is one of the most obvious, the influence that Samaras has consciously or unconsciously exerted on artistic trajectories is thrilling to ponder. In her review of Samaras’s 2003 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Roberta Smith wrote that the artist’s reach on postwar art was pervasive, and a progenitor of more recent trends: “psychedelic color and pattern, labor-intensive craft, homoerotic urges, and fierce performance-like self revelations.” Wed to his hermit life, Samaras confided that he does not meet younger artists, but he said, “Seeing something that reminds me of my work is a nice little kick, like I have a child somewhere.” However, he was quick to add that they should not claim his territory. “A budding artist’s first project must be to come up with something original,” he explained. Because “it’s like blood; it’s there in your system.” Though the body changes – Samaras impressed on me several times during our conversation the specter of decay – the true artistic mission never does.