Everything Falls Apart so Beautifully Cyprien Gaillard

|Gabriel Proedl

Cyprien Gaillard, Retinal Rivalry, 2024 © Cyprien Gaillard. Courtesy the artist, Sprüth Magers and Gladstone Gallery

This feature is from the Summer 2025 issue. Below you can find the full text by Gabriel Proedl, in light of Cyrpien Gaillard's new exhibition at the Haus der Kunst in Munich.

Near the big bridge at the Gare du Nord, where Rue de Maubeuge ends in the Boulevard de la Chapelle, two Parisian skater kids, maybe 13 years old, have used loose cobblestones to build a small obstacle. One of these boys – after flailing his arms and shouting, “Watch, watch,” to the other – actually manages to heave himself and his board over it. A high five with his friend and even some approval from a market vendor here at the Marché Barbès follow. A few seagulls have been pestering him for some minutes, and he tries to shoo them away with a broomstick. Shortly afterward, a drug deal takes place in broad daylight outside the portable toilets.

Cyprien Gaillard, Retinal Rivalry, 2024 © Cyprien Gaillard. Courtesy the artist, Sprüth Magers and Gladstone Gallery

Cyprien Gaillard grew up in this still somewhat rough neighborhood in the 18th arrondissement. A year after our first contact, we finally meet at one of his favorite spots, an unassuming bar tabac on a quiet street corner. It’s a wonder that we’re meeting at all – Gaillard isn’t easy to find. More than ten years ago, when he was around 30 and among the most hyped visual artists at the time, he disappeared from public view, gave hardly any interviews, and refused to be photographed. This era of withdrawal is now supposedly done. Plus, he has been invited to apply for a professorship at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg. The final round of interviews is currently underway. Should he be appointed, his hermit-like life will end.

Gaillard sits outside the café, near the entrance, shrouded in a green parka. Its hood covers the distinctive port wine–colored birthmark beneath his right eye and much of his angular face. Only his shoulder-length hair peeks out. In the ashtray, three stubbed-out cigarettes. He’s listening to “True,” by the band Spandau Ballet, on a continuous loop via his iPhone: So true, funny how it seems / Always in time, but never in line for dreams. “Sometimes, I sit here the whole morning,” he says, his voice husky. “I hate being indoors. When I get up, I just want to go out.” He wants to expose himself to the environment that’s of artistic relevance to him. He says that in the past 20 years, he hasn’t had a single idea at home or in a studio. He now lives as an artist without a studio, as a vagabond. “I like being a little lost,” he says. Besides, he’s always traveling anyway. I plan to accompany him, now and again, over the course of six months.

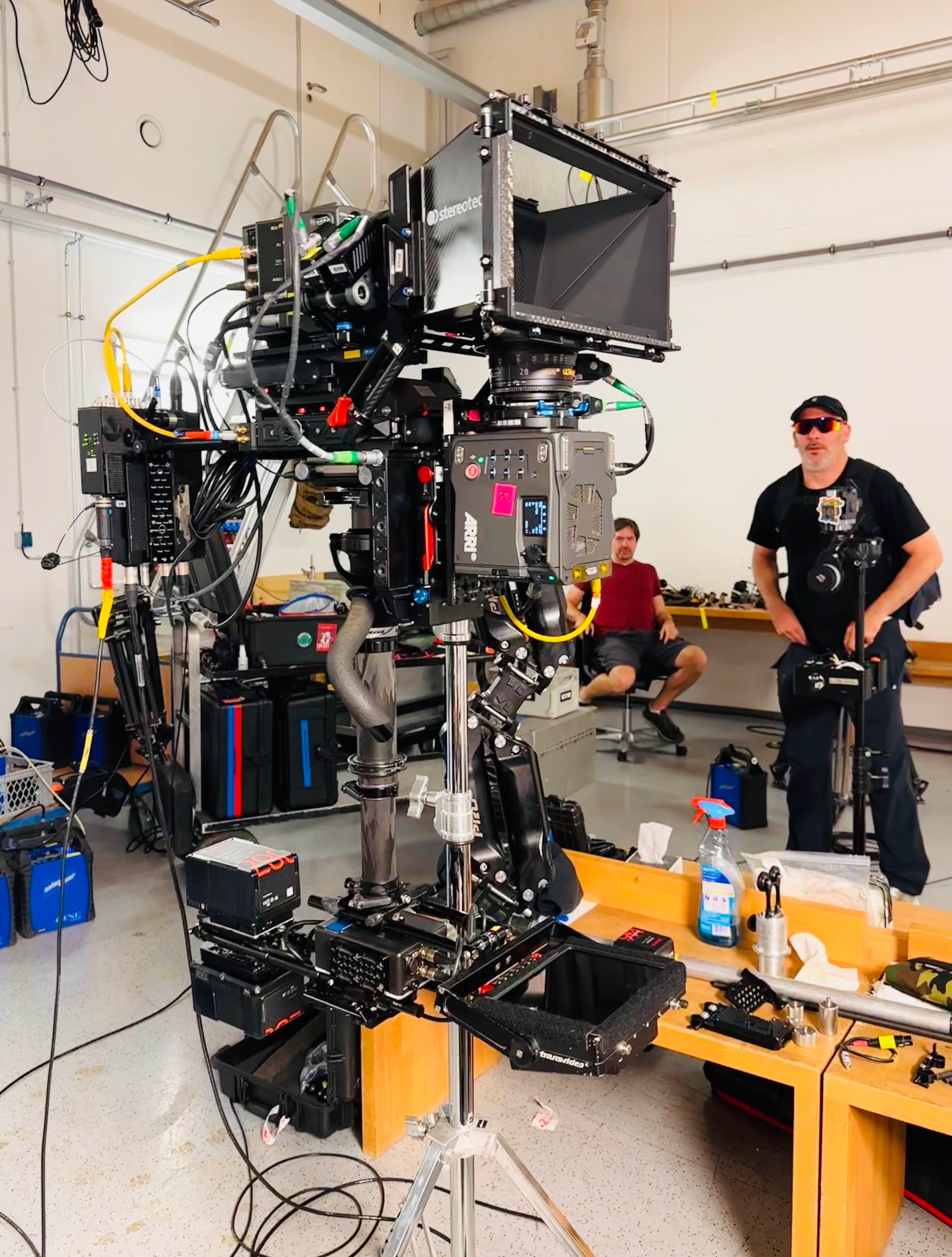

Retinal Rivalry is named after the visual perception phenomenon that occurs when the brain receives two conflicting images at the same time. Instead of blending them into one 3D image, the neural system alternates between prioritizing one image while suppressing the other, causing confusion and discomfort for the viewer. With the film, Gaillard (seated at right) captures more than the human eye can naturally see.

Gaillard’s work isn’t easy to put your finger on. Is it video art? Conceptual art? Field art? In the end, it doesn’t really matter. It encompasses a little of everything, and all of it is done with a deep seriousness. For his work Artefacts, he traveled to Iraq in 2011 with an armed security team of ten people. There, he filmed the remnants of ancient Babylon with his iPhone and documented the constant, human-inflicted debasement of one of civilization’s oldest cities. The city was destroyed several times over, Gaillard says: in the war, through vandalism, and later by attempts at restoration and preservation. The stage: a fragile country. In a T-shirt and a red and white keffiyeh, he stalks through the desert, sits between soldiers in the bed of a Ford pickup, and films the destruction.

His art, he says, is much less about people than about the traces people leave in the world – always within the complex relationship between nature and culture. Gaillard celebrates decay, aesthetic destruction. Off the coast of New Jersey, he recorded the sinking of decommissioned subway cars, which were soon to serve as artificial reefs hosting coral. Before that, he documented numerous detonations of buildings, a monstrous event, the beauty of which eventually floored even those who had been against it. Gaillard’s video recordings constitute a reminder that our civilization will be followed by another, and that at some point everything we’ve cherished will be not only destroyed but also forgotten.

Cyprien Gaillard, Life in the Cracks (Part 1), 2025

This series of fabric-wrapped acoustic panels, salvaged from the gutted auditorium of Trieste’s Museo Revoltella, bear a pattern of repeated touch: past visitors brushed against the fabric, leaving marks that turn the surfaces into modern cave paintings. Each work features a single hand-embroidered motif.

Here, in the 18th arrondissement, where Gaillard spent his early childhood, and later in California, he tore through empty subway passages on his skateboard, roamed abandoned buildings, loitered on street corners. These experiences made him an explorer, an artist, he says. He broke his bones but sharpened his eyes. Many of these places are now either destroyed or abandoned, or they have been cheaply renovated, which often amounts to the same things.

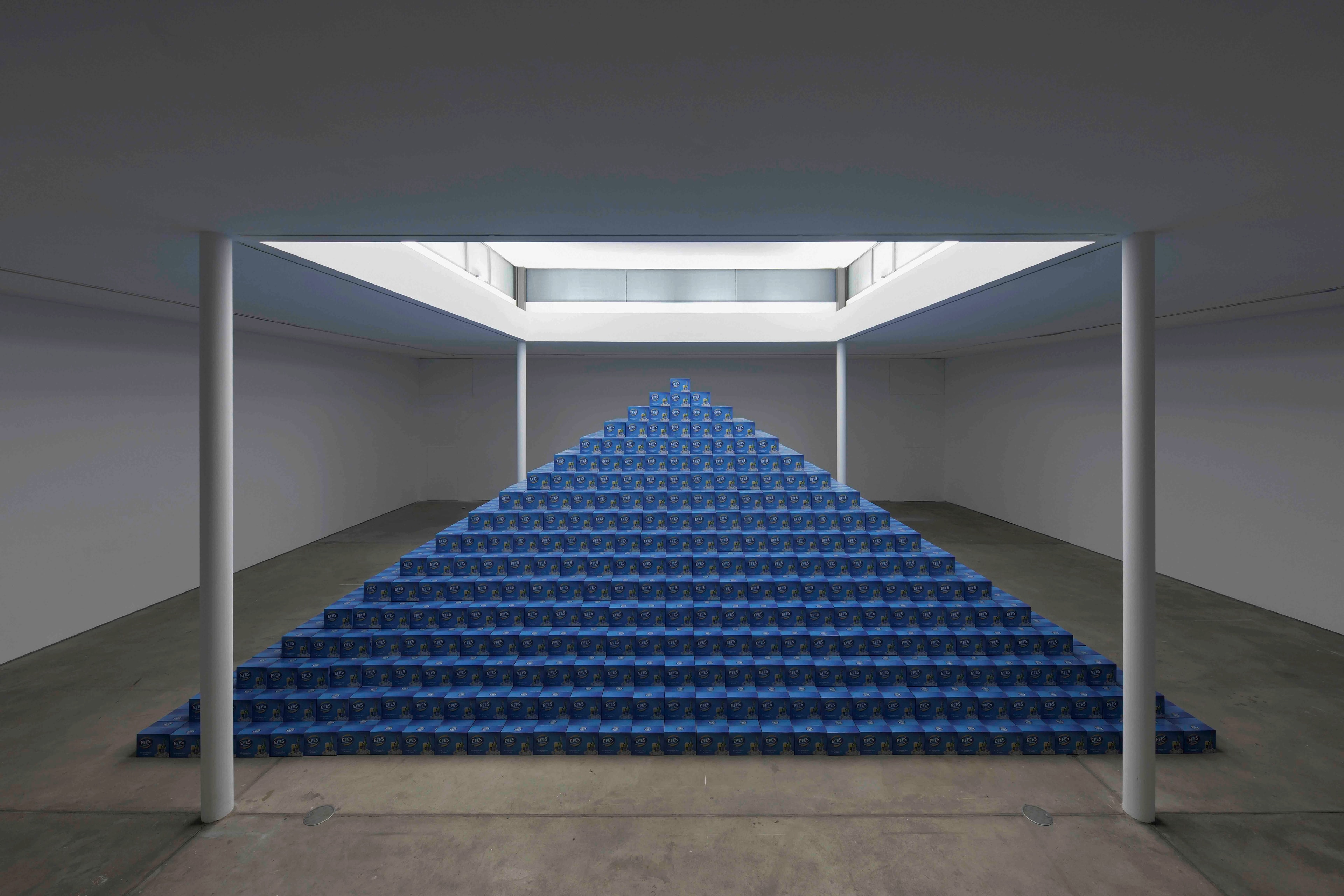

One of Gaillard’s most memorable installations was on view inside Berlin’s Kunstwerke in 2011: he stacked 72,000 bottles of Turkish Efes beer, in their blue cardboard boxes, into the form of a stepped pyramid and encouraged visitors to help themselves. Over the course of two months, the sculpture was repeatedly renewed and torn down, until all that remained was sheer devastation – referring to the ancient site of Ephesus, the work’s eponym and a place looted by Western archeologists, who took pretty much everything they could carry. The trauma of colonialism.

Cyprien Gaillard, Ocean II Ocean, 2019, film still Courtesy of the artist and Sprüth Magers

Munich, in December. We meet at the Hofbräuhaus. Gaillard loves the place. A small music ensemble plays Bavarian folk music. The accordion fights to rise above the din of the drinkers. Gaillard grins. A living demolition. He has lived in Germany for years. In Berlin, he has been able to find peace in the country because he doesn’t really understand the language. No news from Hamburg yet. He’s still waiting for the final word on the professorship. He drums his fingers against the heavy wooden table. He traveled to Munich with his assistant, Max Paul, himself an artist and trained architect – Gaillard’s executive power. We walk to the Haus der Kunst, where the two of them are conducting research. They keep drilling each other: “What could this material be?” Gaillard asks, as he points at the sculpture of a lion. “Guess the age of this thing,” Paul says while devilishly grinning and covering the plaque with his shoe. This is the duo’s way of working, a never-ending conversation, an endless chat, a bubbling desire to share thoughts, back and forth, until a quote drops or an idea takes shape. That’s how a piece slowly emerges.

The themes for Gaillard’s work in the Haus der Kunst are already established. The building’s history is a textbook example for the debate on the preservation and destruction of buildings that can be read like CliffsNotes: commissioned by Hitler, built by Troost, neoclassicism. In the 1950s, an architectural attempt to create distance: 16 maple trees were planted between the façade and the street. They’re due to be removed again. David Chipperfield’s going to do it. The “green curtain,” as he calls it, was never a serious examination of the past – just repression. An outcry in the city, it’s billowing again, and Gaillard pierces into it. “It’s an interesting debate,” he says. “I call it the perpetual challenge of preservation. It’s a balancing act: Which elements do you take care of and which elements do you tear down? A constant negotiation. Never a tabula rasa.” In the archive of the Haus sits the model of a student’s counterproposal: the building is entirely demolished; only the 16 trees are still standing. Gaillard chuckles. “What do you think the building wants?” he asks Paul. “That’s something we don’t ask ourselves enough: What does the building want?”

Cyprien Gaillard, The Recovery of Discovery, 2011

In what is arguably his best-known work, Gaillard stacked 72,000 beers imported from Turkey into a pyramid and invited viewers to climb up and have a drink. The public’s interaction with and inevitable destruction of the pyramid speaks to colonial tourism and how the context of a monument changes as it is destroyed or relocated. Photos: Uwe Walter, Josephine Walter, anna.k.o.

A little later, he spots a fossilized ammonite in the marble. Reverently, he kneels down to it. “The ammonite could be the answer to this question.” The fossil has been trapped in metamorphic rock for maybe 200 million years. And now it’s here, in the Haus der Kunst, in Munich, in Bavaria. Paul nods. The natural history of materials is rarely included in the discussion. After all, a building doesn’t just come into being during its construction. “Maybe we should look at the life span of a building not only from the perspective of cultural history but also from natural history,” Gaillard says. He and Paul stroke the cold marble surface. They take pictures of the ammonite with their iPhones. It’s set to become a central fulcrum of his next work. “What kind of music would an ammonite like to listen to?” Gaillard asks. Later, he makes a couple of suggestions himself: Coil’s experimental “Dark River” and Burial’s idiosyncratic dubstep mix, “underground. Typical ammonites.” Or, of course, Spandau Ballet’s “True” again: Take your seaside arms and write the next line / I want the truth to be known.

We continue wandering through the archive and amid all the exhibited items, the aggregate of furniture, models, and paintings, but it’s the carpet on the floor that Gaillard notices: over the years, footprints have eaten into the fibers from above, and the stone floor has done the same from below. Humans have inscribed themselves into the material – that’s what he calls it. He asks the Haus’ archivist for permission to use the carpet in one of his works.

Cyprien Gaillard, Ocean II Ocean, 2019, film still Courtesy of the artist and Sprüth Magers

For the umpteenth time, he wants to explore the building’s history through art; he’s already addressing it in his current work Retinal Rivalry. It’s his next big show after his acclaimed exhibition “Humpty Dumpty” at Paris’ Palais de Tokyo and Lafayette Anticipations in 2023. The half-hour film – which is currently being shown at the Sprüth Magers Gallery in Berlin – is, at first glance, a classic journey through Germany: a wide shot of the Theresienwiese during Oktoberfest, hiking trails in Saxony, the Michael Jackson Memorial at Munich’s Bayerischer Hof. The Haus der Kunst is also shown. The method, though, is somewhat more unusual and, technically, very complex. He films the everyday scenes with two high-resolution Arri Alexa 35 digital cameras, whose function of recording at 120 frames per second is designed for super-slow motion. The two images from the cameras are then superimposed to create a 3D film that is then also projected into the exhibition space at 120 frames per second. This rate is about five times the standard in cinemas. Only three laser projectors in the world can handle this speed. Due to the high frame rate and the tremendous brightness of the 3D images, the world briefly appears as if seen through the compound eyes of a fly. “Animist vision” is what Gaillard calls it – stereoscopic images that are not dictated by any obvious narrative structure. The Roman ruins beneath the Cologne Cathedral, a Burger King at a transformer station in Nuremberg. Later, the footage was spatialized – “shaped,” Gaillard says, in the language of a sculptor, in a rented cinema in Berlin. Gaillard and his team sat together for ten days while shaping the film. Viewers actually have the feeling of being inside the scene: we crouch inside a shipping container, we kiss the glass that will be recycled. The film curves inward as much as it bulges outward, toward us. “I hijack the technology because I have no cinematographic ambitions, just sculptural ones,” Gaillard says. Film as a body. Cinema as a psychedelic event. His cameraman didn’t understand, at first. Why go to all the trouble, he asked. Gaillard sees this reaction as a fundamental misunderstanding of artistic work: “We often want to use technology to realize our own vision. But we never ask the stone how it wants to be carved. We never ask the camera what it wants to see.” And the camera wants to see everything that’s there. Devour it all, like a data-eating dragon, Gaillard says. The project was so expensive that it had to be supported by several institutions, including the Fondation Beyeler in Switzerland, OGR Torino, and even the Haus der Kunst in Munich.

Gaillard has often referenced the artist Robert Smithson, who once quoted Vladimir Nabokov: “The future is but the obsolete in reverse.”

In the drizzle, I shuffle back, alone, to where it started, to the café on the corner in Barbès, where the kids hang out, where the cobblestones are missing from the street and the plaster from the walls, where the seagulls pick at the last scraps of fish. Everything falls apart so beautifully. “To go where reality is,” is how Gaillard calls it, “feeling life on your skin, enduring the contradiction.” I put on Spandau Ballet: I bought a ticket to the world / But now I’ve come back again. A harmless song, a cute melody. But “Spandau Ballet” was what soldiers called the twitching of dead comrades who had been hit by an MG 08 machine gun, commonly known as the Spandau MG. I look toward the Gare du Nord. When Gaillard and I took the train back to Paris from Munich a few weeks ago, we made a brief stop at Lake Constance. The water was just above freezing. We stripped naked and jumped in.

Paris, a month later. We meet in Café Le Bistrot in the 9th arrondissement, in the covered arcade on Rue de la Grange Batelière. The waiter sloppily clears the chalkboard of the day’s dishes, leaving behind a smear of water and chalk. Gaillard lights a cigarette; the ash falls onto his iPhone’s display, on the bistro table. His eyes are tired, his hair buzzed short; it’s less work that way. He’s in a tunnel, as he puts it, hyperfocus for the projection at the beginning of May. A long drag on the cigarette. He crosses his legs. The professorship: he received it. He blows out smoke. He’s pleased. In Gaillard’s life, there’s now a place he can return to. The land artist and his site. “What will you teach?” I ask.

“I can only teach what I have mastered myself,” he says, “what I’ve been doing every day for more than 20 years: sharpening my eyes.” Cigarette.

“Will you produce something with the students?” I ask.

“Of course,” he says. “But more than anything, I’ll talk about what it means to put an artistic object in a world that is literally collapsing from all its objects.”

“The perpetual challenge of preservation?” I ask.

Gaillard thinks about it. “Yeah. You can’t talk about preservation without thinking about destruction.” As soon as something is over, it’s obsolete.

Cyprien Gaillard, Retinal Rivalry, 2024 (film still) © Cyprien Gaillard. Courtesy the artist, Sprüth Magers and Gladstone Gallery

Credits

- Text: Gabriel Proedl