Embracing Vulnerability with Michella Bredahl

|PAIGE SILVERIA

“It was really intimidating at first because I didn’t always feel comfortable

being undressed in front of people,” explains photographer Michella Bredahl about trying out pole dancing for the first time. “At the same time, I think that’s also why I started taking classes, because I want to feel more comfortable in my body. I’ve photographed dancers for years. I always saw this confidence in them, which I find so fascinating.”

Gwen in her room, 2024. Gelatin silver print on Kodak Endura N paper. Courtesy the artist and everyth!ng

Her new book, everyth!ng 001 (2025), is a collaboration with stylist Lotta Volkova and features 26 intimate shots of pole dancers in their Parisian homes and studios, styled in Miu Miu AW-24. The collection of photographs continues Bredahl’s ongoing investigation of femininity and the self as well as the lasting impacts of early familial experiences and how art can offer community and catharsis. “Dancing or any art form, can be a way of liberating yourself or turning darkness into light,” she explains.

Paige Silveria recently spoke with Bredahl about pole dancing, outsider art, and transforming trauma into beauty.

Portrait of Michella Bredahl.

PAIGE SILVERIA: Are you pole dancing yourself?

MICHELLA BREDAHL: Yeah, I have a private teacher and it’s wonderful. I like to be sportive, but this tops everything.

PS: Was it intimidating when you first started?

MB: It was really intimidating because I didn’t use to feel comfortable being undressed in front of people—or being looked at while I felt vulnerable. At the same time, I think that’s also why I started taking classes, because I want to feel more comfortable in my body. I’ve photographed dancers for years. I always saw this confidence in them, which I find so fascinating.

PS: How did you initially get into it?

MB: Five years ago, I made a film about a group of dancers called Chassé (2019), which included two pole dancers. Watching them really touched me. One became my friend, and we started taking classes together.

PS: Would you ever perform in front of people?

MB: Yeah, maybe if I ever got comfortable enough with it. I think it could be fun to do at a party or something. I don’t think I would ever try to become a professional pole dancer; it’s more something I do to have fun and feel beautiful. But you never know.

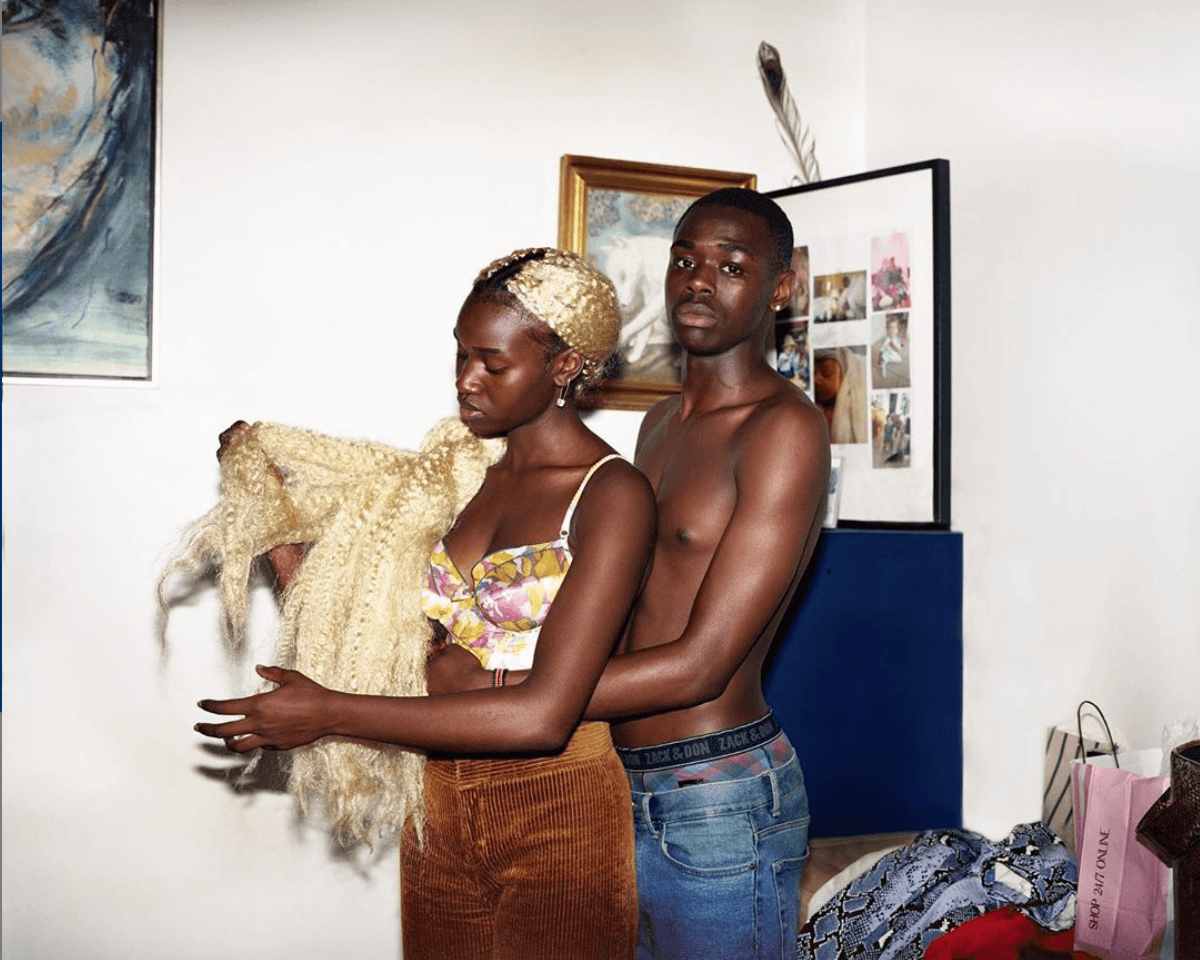

Billie and Louis, 2021. Gelatin silver print on Kodak Endura N paper. Love Me Again. Courtesy Loose Joints

PS: What made you think of working with Lotta Volkova on this project and dressing everybody in Miu Miu? I love the contrast between the subjects and the settings with the styling.

MB: Lotta and I were waiting for the right project. We’d talked about it back and forth for a while, and then I got this idea and sent it to her. I’d already been shooting pole dancers and taking classes when this idea came to me—when you take classes with a teacher, you often go to their home where the pole is. This idea started because I’m very fascinated with the home and intimate spaces in my work. I thought it’d be interesting to do this series of portraits of pole dancers in their homes.

PS: Dancers usually have poles in their homes? That’s more common than going to a studio?

MB: Not everyone, but most install them in their homes, because it can cost a lot of money to have to go to a place and pole. It’s really easy to just have them in your home. It gives you access to pole dancing at any time, which is convenient.

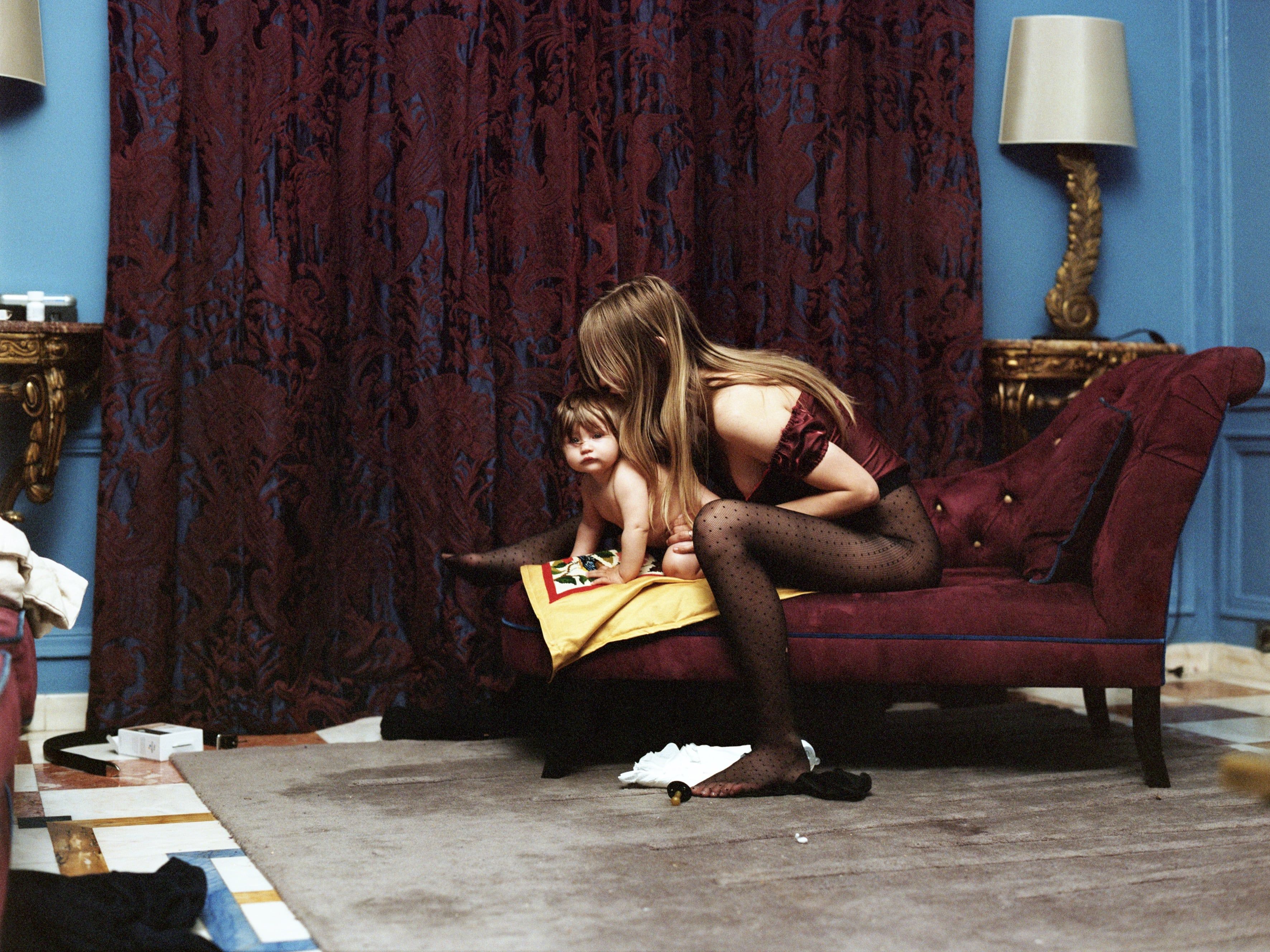

Klara sleeping with baby, 2022. Gelatin silver print on Kodak Endura N paper. Love Me Again. Courtesy Loose Joints

PS: But yeah, sorry, back to the book and the styling.

MB: So, then we started talking about this idea of dressing the dancers. It’s actually really hard to pole in clothes because you need bare skin to have enough grip. We knew it was going to be an experiment, but I talked to all the girls. And they were like, “Okay, we’ll try!” They had to get creative about how they were going to use their arms or do a certain pose. It was interesting to bring this clothing collection into another environment where you would normally not see it.

PS: Let’s go back to the beginning. Can you give me some background on yourself?

MB: I’m from Denmark, outside of Copenhagen. I went to the Danish film school, so I have a degree in film directing. I made several short films. But before that, I photographed as well, which would lead me to study cinema.

PS: And why/when did you start shooting?

MB: My mom gave me a camera when I was little, around seven years old—I grew up with my mom and my sister. I think my work is an extension of those years with the two of them. It’s a lot about femininity, motherhood, siblings, girls, female sexuality, and all these extensions of what I was surrounded by when I was young and started photographing. The first portraits I ever took were of my mom and sister, and then it led me to photograph my friends and their friends. I always had the camera with me, and I have so many pictures.

Clive in Tonia, 2019. Gelatin silver print on Kodak Endura N paper. Love Me Again. Courtesy Loose Joints

PS: The publisher’s description for your previous book, Love Me Again (2022), reads: “Raised in a turbulent home environment within the Høje Gladsaxe Vulnerable Residential Area outside of Copenhagen, the artist eventually found herself before the camera, scouted as a model at a tender age: objectified, gazed upon, subjected to the whims of men and power. Love Me Again is an exercise in taking that power back, by locating the essence of femininity alongside sexuality, safety, and the plain unfiltered reality of her subjects.” This book sounds very personal. What was it like to share these intimate images with everyone?

MB: All the photos in this book are an extension of my mother and sister, so it’s very personal. I think being personal has a price, but it also gives you a lot in return. It means a lot to me when someone writes that my photos have had an impact on them and made them feel seen and included. My camera is my heart, a way to share my life and the beauty that surrounds me. My friends are a part of that. Photography started from a difficult place but has now become a way where I’ve been able to turn the difficult things that affected my childhood into opportunities and transformation. Sometimes it also feels a bit like I’m living out the dreams my mother had, and it gives me a feeling of repairing something much deeper.

PS: What’s your experience with taking and organizing still images for a book in contrast to shooting a film?

MB: Photography and film are two very different things. I can do photography on my own, but film requires so many people involved. But I think I have the same approach to photography and film. I work very spontaneously and closely with those I photograph or film. With a film crew, I try to create a very close bond, so that my film crew becomes an extension of me. At the same time, I bring something of them into the film. When I make films, I have to let go of control more so that those working on the film can also influence the film.

PS: Tell me more about your film Chassé, which is similarly incredibly intimate and also heartbreaking.

MB: The name comes from ballet. It’s a dance step where one foot “chases” another in succession. It also means “to be chased.” With the film, I wanted to talk about hereditary neglect, about being brought up in a family where you haven’t been given the right tools, where you haven’t had loving parents. In that situation, dancing, or any art form, can be a way of liberating yourself or turning darkness into light. So, in the film, I had a group of girls talk about their families, their neglect. And then I had some of their mothers, who were also performers, talk about their own abandonment and how it’s generational. How do you deal with that? Dance is an outlet. And for me, photography is similar—it’s a way of transforming my feelings into beauty, an outlet to express myself. Photography can be a bit misunderstood; it’s not necessarily just a portrait of the person in it. It’s like a conversation. It’s transformative.

PS: Are you planning any films currently?

MB: I just talked with my friend from Georgia and we’re planning a road trip with her and her daughter who’s seven. We’re going to take the car and I’ll film the trip. We’ll see what happens. I like working like that. Just going somewhere. I’ve been wanting to make a film about a story that’s positive, about a kid that’s happy, for a long time. I want to see that.

PS: I was thinking recently, how kids always say to adults, “You don’t know what it’s like to be my age!” It’s crazy to realize that I’ve reached that age where I don’t remember. I don’t necessarily understand what it’s like to be them. And I wonder what I might have lost with that knowledge.

MB: Kids are like philosophers, and they see so many things that we don’t. It’s interesting to also learn that the people who went through the most trauma sometimes end up being the most creative. Trauma is a gift and a curse. It’s survival. That’s how I see it. That’s why really strong art often comes out of pain. Not that it always has to be that way, but art can be a way for someone to hold on to something in all the chaos that can give you a direction and hope, so that you don’t give up. At least that’s how it has been for me since I was kid and got a camera in my hands.

Tonia and Clive, 2019. Gelatin silver print on Kodak Endura N paper. Courtesy the artist

PS: Yeah, some of the most creative people used their well of trauma to transform it into something beautiful.

MB: I see it as balancing on a very thin line, if you’ve had a very traumatic childhood. Because it could either give you strength to lift you—it can be a fire to fight against—or it can drag you down. Which way you go is not necessarily a choice, but I think that you can meet that one person who can change the course of your life, that can teach you that you don’t need to go that way. They can teach you about your potential as a creator and give you the confidence that you maybe didn’t have. Even for myself, some of the people I met through my life, I think they gave me confidence that I didn’t have, and that made me continue.

Sometimes creative friends tell me people say horrible things about their work. Somehow people are so insensitive to each other on social media. It’s so awful. I always think about a little kid making artwork. You’d never tell a kid that their work is horrible and to stop drawing. Just give people credit for trying to create something, even if you don’t like it. Of course people are going to make mistakes. But we’re never going to get anywhere if we don’t try. That bullying or negativity is why a lot of people stop creating, sometimes when they’re really young. It can be heartbreaking. I don’t like it. It can be much more loving. We are put on earth to love and not to hate on each other.

PS: I think the community could also be a bit more supportive of outsider artists or creatives making work in unconventional ways. Or those who are pursuing careers without a formal education. I don’t understand the stigma against being self-taught.

MB: I agree. Maybe they’re inspiring people to do things in a different way. I think it can make some people feel uncomfortable when someone’s doing something else; often, people who are insecure will then try and trigger you to feel insecure as well. I took a masterclass with Pedro Costa, who is an amazing film director. His advice was: make a film on your iPhone. Don’t fall into the trap of thinking there is one way to make a film, and that you need a lot of money. Often money can result in limitations. Something is only normal until you are aware that something else is normal.

Siblings Martha, Alma, Olga and Asta in their home, 2023. Gelatin silver print on Kodak Endura N paper. Courtesy the artist

PS: You need to stand strong and figure out your own path sometimes. Maybe you don’t even know what you’re doing. But you just have faith in the process and in yourself.

MB: How are we going to progress if we just do things exactly the same way? And on another topic, thinking of cinema, if you look at early films, it’s just someone with a camera. Why does there need to be a huge production with so much money involved to make a film?

PS: And sometimes not having money forces you to be way more inventive.

MB: Right? Then maybe you’ll make a film on your iPhone. I was reading Luis Buñuel’s biography—he was a filmmaker and writer, who made this short film called An Andalusian Dog (1929). The book talks a lot about how he made this short film with his friend. It was based on a conversation between the two friends and a dream that the two had had in particular. The process was really messy as I remember it. The guy who was supposed to handle the camera never showed up and they didn’t have an editor—Buñuel edited the film himself. He borrowed money from his mother to produce the film. And now this film is exhibited as a masterpiece. It is one of the best-known Surrealist films from the French avant-garde film movement of the 1920s. They did these amazing shots, like this horrible scene where a girl’s eyeball gets cut. Though it should be said he came from a wealthy family, he used the cards he was given.

Klara with baby in Paris, 2022. Gelatin silver print on Kodak Endura N paper. Love Me Again. Courtesy Loose Joints

PS: You mentioned earlier that femininity was a particular focus in your work. Can you expand on this a bit more?

MB: I just think about femininity in all aspects—not just women—because I don’t think femininity only belongs to women. It’s an essence that I am looking for. I photograph a lot of my friends, in spaces where I feel safe. In school, we were taught that it was cheating if you became friends with the people you photograph. For me, it’s about exchanging and making friends and sharing and having fun. Allowing whom I’m photographing to be vulnerable because of that honest exchange. I think that’s important. Like, what’s the goal if you’re trying to keep that distance?

PS: Like, let’s evolve together and learn from one another and go through a process and reach another point, right? It can’t be just about the market and making money.

MB: You never know what you can learn from someone. Sometimes I meet people and as soon as they reach a level of success, they become so arrogant. This is something that I never understood. Just be humble—because you never know. And in the end, we’re all equal. We all have so much to learn from one another because we all have totally different experiences.

PS: I always loved Socrates. He was called the wisest man in Athens because he acknowledged his ignorance while others boasted more knowledge than they actually retained. And I love how Marx said that human relationships are the most important thing in life. This exchange of ideas with one another.

MB: With photography, it creates a way for you to meet a lot of different people that you might not necessarily engage with but that you get to know about and get to hear their stories. That gives you a wider understanding of what it means to be a human being … [Looking down at her phone.] It’s so funny; one of the girls that I photographed just sent me the picture I took of her, which was turned into a meme. The world is so absurd. I don’t get the joke at all.

PS: What does it say?

MB: “Chicken Caesar wrap and a Diet Coke for lunch.” But it’s really cute. It was reposted so many times. I love her response: “This is me and this is how I watch TV by the way.” The picture is of her doing the splits on her couch.

Credits

- Text: PAIGE SILVERIA